Adding Beauty to Holiness: The Washington Haggadah

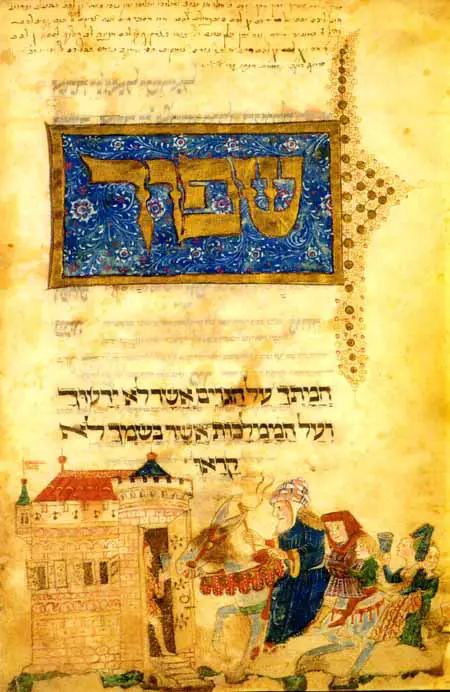

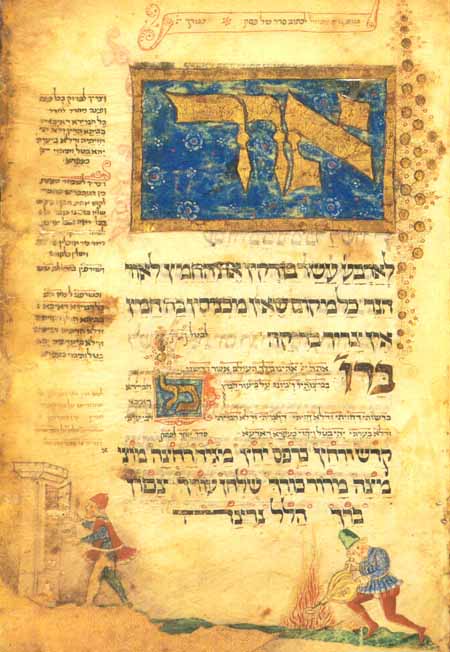

Even more than the megillah of Esther, the Haggadah which is read in Jewish homes at the Passover seder, and which tells of the Exodus from Egypt, has been reproduced in many and varied forms of artistic decoration. An illuminated manuscript Haggadah, also fashioned in northern Italy, is the Library's justly famed Washington Haggadah. The anonymous artisan who produced the megillah was a pedestrian calligrapher and illustrator and, perhaps precisely because of that, his megillah has a folk vitality and naive charm often lacking in the work of more sophisticated and gifted artists. It is a fine example of what a moderately skilled scribe aspiring at hiddur mitzvah can accomplish. As such it is a valuable contribution to Jewish folk art. The Washington Haggadah is of another order. Its creator, Joel ben Simeon, was the most prolific Hebrew artist-scribe of the fifteenth century. No less than eleven manuscripts bearing his name, written in his native Rhineland and in Northern Italy, are now the treasured possessions of libraries in Europe, Israel, and America. "Most of Joel's illuminations," Bezalel Narkiss writes, "consist of colored pen drawings.... The best ... is the expressively drawn Washington Haggadah of 1478." Narkiss includes it among the sixty beautiful and important works which comprise his Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts, first published in Jerusalem in 1969, and more recently in 1984, in a revised and improved Hebrew edition. He describes it:

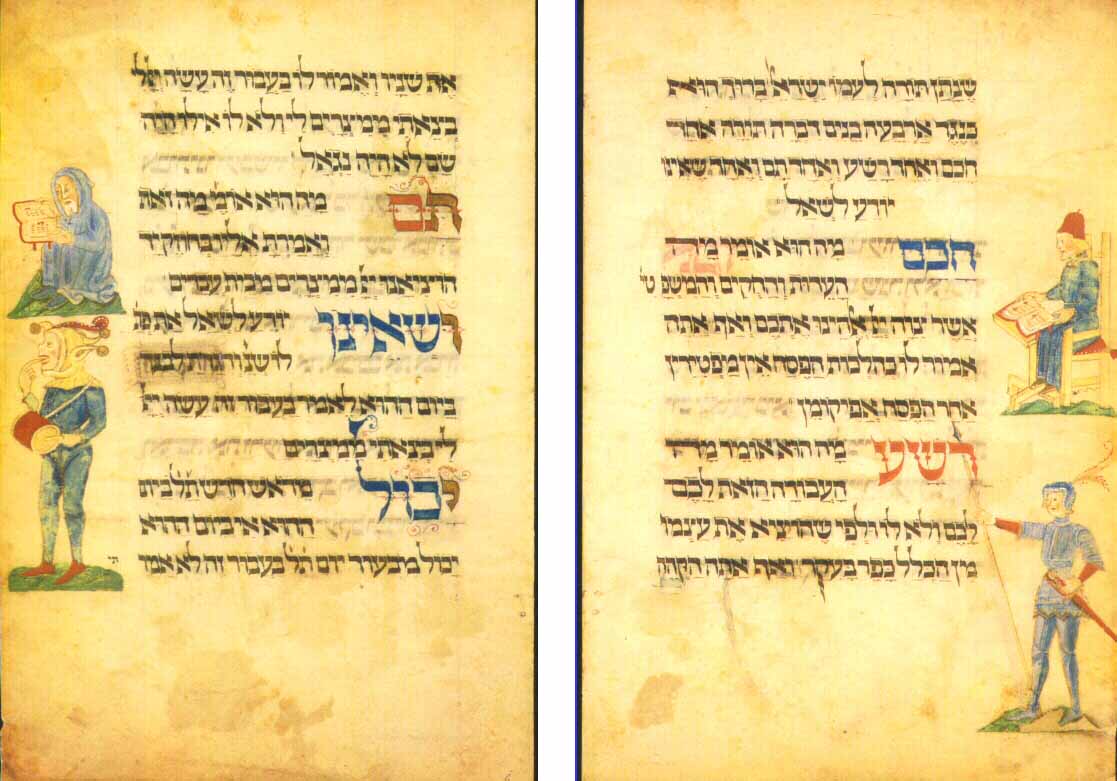

It is illuminated entirely in Italian style, with no trace of German motifs other than the iconography. All of the illustrations are placed in the margins, and are mainly ritual or literal ... Beside the four sons, other illustrations typical of German iconography are the cooking and the roasting of the Passover lamb and a man pointing to his wife while saying maror zeh.

Joel ben Simeon, called Feibush Ashkenazi of Bonn, calls himself the humblest of scribes, stating that "the work was completed on the 25th of Shevat, 5238" [January 29, 1478].

What appeals most to this observer about the Washington Haggadah is its economy of decoration and its use of the illustrations, even their place upon the page, to express a point of view. Illustrations are only in the margins, preserving the centrality of the text; decorations are there to adorn and may not intrude upon the text. The wise and wicked sons are and should be farther apart from one another than the simple sons. Why should the wise one not seem to be shoving the wicked one downward? More than half of the figure of the wicked son is below the text, removed from it, as the wicked son "removed himself from the congregation [of Israel]." The artist becomes the subtle commentator, in the tradition of Jewish religious works: text and commentary.

|

Speaking of the sons: the wise one sits on a chair, book in hands on lap, as if in the process of teaching. The simple son is not a simpleton; he too has a book before him, but he sits on the floor as an inquiring student. He does ask, "What is this?" and in a question is the beginning of wisdom. The artist-scribe does not fall into the error of so many illustrators of the Haggadah who depict the tam as a simpleton, a tradition brought to a head by Jakob Steinhardt who places a dunce cap on the tam in his Berlin, 1923, Haggadah. Tam means innocent and simple, honest, and harmless. A faith tradition which extols the question-the Talmud begins with a question, the Haggadah itself flows from the Four Questions-would never view a questioner as a simpleton. A simpleton is one who "lacks the capacity to ask a question," and he is so portrayed in the manuscript, as a fool or jester. Our artist-scribe knows he is a scribe first, copying a sacred text, then adorning it and illuminating it with subtle visual commentary, but the text must dominate.

|

|

There are a considerable number of illuminated Haggadot, larger in format and richer in illustrations. They are finer artistic creations than the Washington Haggadah, but very few, if any, are grander Haggadot, i.e., sacred liturgical texts whose purpose is to help the celebrant reexperience history and renew his appreciation for the gift of freedom. Its modest size, six inches by nine, indicates that it was meant to be used at the seder table, and the pale wine stains on its vellum bear witness that it was.

|

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).