Adding Beauty to Holiness: Nineteenth Century Illustrators

In the nineteenth century, illustrators departed from the slavish copying of the early Venice editions by Italian publishers, and of the early Amsterdam by central and eastern European printers. A most attractive edition, both for its Hebrew typography and its elegantly executed woodcut illustrations, was published in Basel in 1816, by Solomon Coschelberg at the press of Wilhelm Haas. It is, as stated, "a simple edition without commentary ... but a correct text, printed in large letters and with many appropriate illustrations." The illustrations, twenty-four in number, are copied from Friedrich Battier's, which appeared in a 1710 edition of a Basel German Bible. The spare woodcuts and the square Basel type blend harmoniously. One note which may raise an eyebrow is the depiction of a seder scene with twelve men surrounding a long-haired central figure seated at a set table, the classic portrayal of the Last Supper. A seder scene, to be sure, and one fraught with memory. It must have escaped the scrutiny of the Jewish publisher, because it was hardly an appropriate replacement for the historic seder scene of the Amsterdam edition in which "Rabbis seated in Bnei Brak are discussing the exodus from Egypt," or the contemporary seder shown in the Venice editions.

|

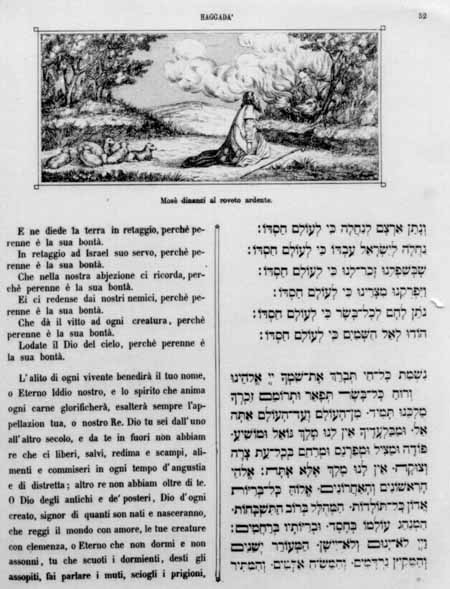

The beautifully illustrated Trieste, 1864 Haggadah was published by Colombo Coen (Joshua Cohen) and edited by Abraham Hayyim Morpurgo, the editor of Corriere Israelitico and scion of a noted scholarly Italian Jewish family. The illustrations are by a young artist, K. Kirchmayer whose name is inscribed at the bottom of the title page, on which appear David and Solomon crowned, Aaron mitred, and Moses bareheaded, rays of light shining from his brow. Most of the illustrations are updated redrawings of those found in the Venice editions. Thus, father and son still search for leaven, mother is still doing her pre-Passover cleaning, but they are now dressed in modern clothing, and the house furnishings are those of a mid-nineteenth-century middle-class Italian home. This edition, too, has a jarring note. Moses is depicted kneeling before the burning bush, and clearly visible in the bush is the bearded face of God. The figure and face of God can be seen in many Christian biblical illustrations, but this is the only one in a Jewish publication, except the barely noticeable face of the divine in the "Ezekiel and the dry bones" panel on the engraved title page of the Minhat Shai edition of the Hebrew Bible, published by Raphael Hayim, Italia, Mantua, 1744. Did both Cohen and Morpurgo overlook it or, seeing it, did they deem it appropriate?

|

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).