Myths & Facts 2023:

Chapter 2: The British Mandate Period

By Mitchell Bard

The British helped the Jews displace the native Arab population of Palestine.

The British allowed Jews to flood Palestine while Arab immigration was tightly controlled.

The British changed their policy to allow Holocaust survivors to settle in Palestine

As the Jewish population grew, the plight of the Palestinian Arabs worsened.

Jews stole Arab land.

The British helped the Palestinians to live peacefully with the Jews.

The Mufti was not a Nazi collaborator.

The bombing of the King David Hotel was part of a deliberate terror campaign against civilians.

The British helped the Jews displace the native Arab population of Palestine.

FACT

Herbert Samuel, a British Jew who served as the first High Commissioner of Palestine, placed restrictions on Jewish immigration “in the ‘interests of the present population’ and the ‘absorptive capacity’ of the country.”[1] The influx of Jewish settlers was said to force the Arab fellahin (native peasants) from their land. This was when less than a million people lived in an area that now supports more than nine million.

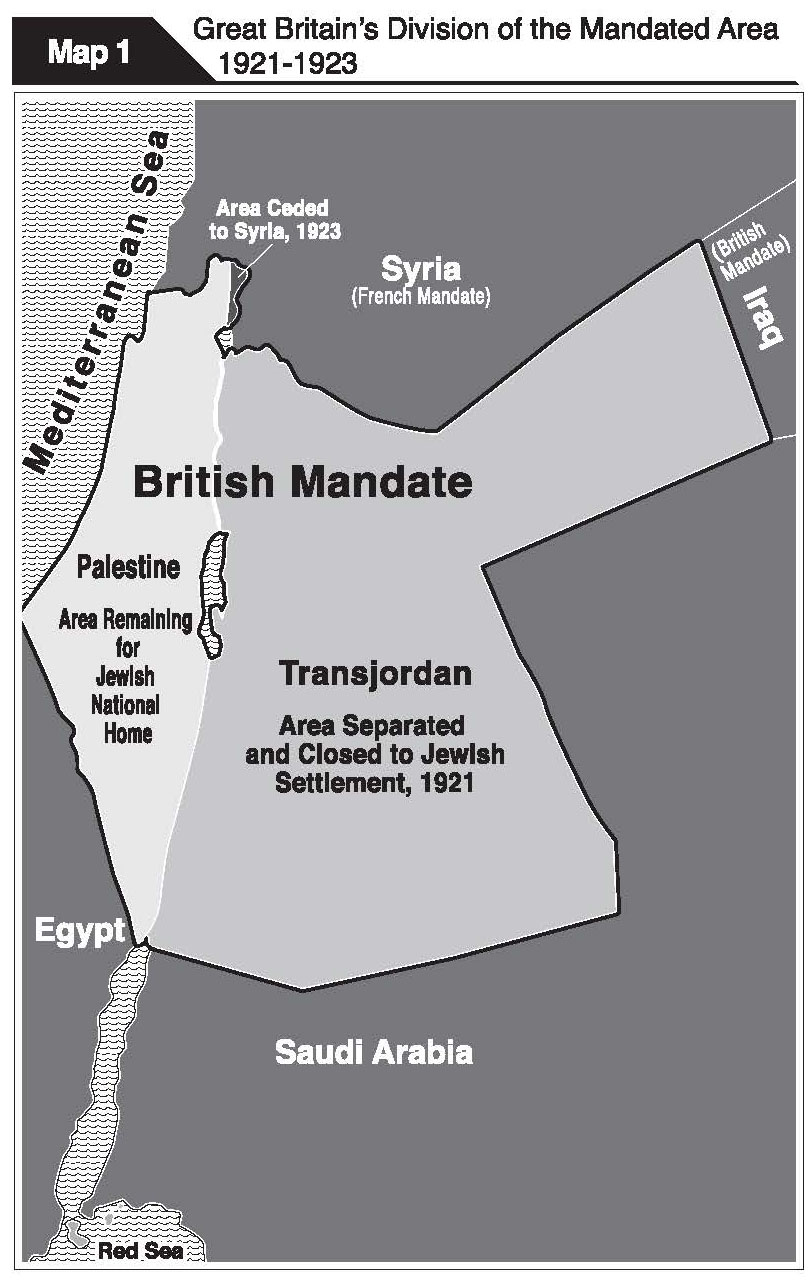

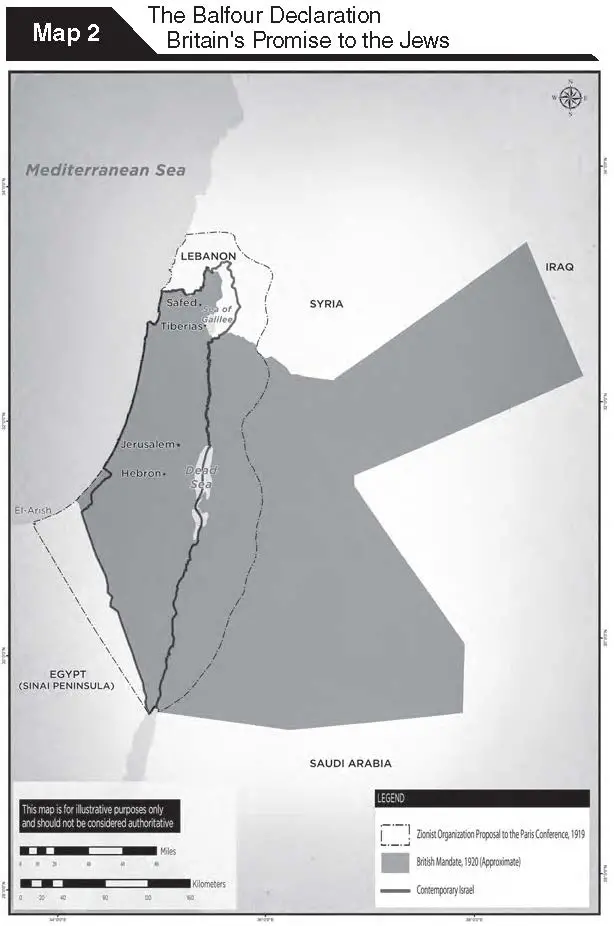

The British limited the absorptive capacity of Palestine when, in 1921, Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill severed nearly four-fifths of Palestine—some thirty-five thousand square miles—to create a new Arab entity, Transjordan. As a consolation prize for the Hejaz and Arabia (which are both now Saudi Arabia) going to the Saud family, Churchill rewarded Sharif Hussein’s son Abdullah for his contribution to the war against Turkey by installing him as Transjordan’s emir.

The British went further and placed restrictions on Jewish land purchases in what remained of Palestine. By 1949, the British had allotted 87,500 acres of the 187,500 acres of cultivable land to Arabs and only 4,250 acres to Jews. This contradicted Article 6 of the Mandate which stated that “the Administration of Palestine…shall encourage, in cooperation with the Jewish Agency…close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not acquired for public purposes.”[2]

Ultimately, the British admitted that the argument about the country’s absorptive capacity was specious. The Peel Commission said, “The heavy immigration in the years 1933–36 would seem to show that the Jews have been able to enlarge the absorptive capacity of the country for Jews.”[3]

The British allowed Jews to flood Palestine while Arab immigration was tightly controlled.

FACT

The British response to Jewish immigration set a precedent of appeasing the Arabs, which was followed for the duration of the Mandate. The British restricted Jewish immigration while allowing Arabs to enter the country freely. Apparently, London did not feel that a flood of Arab immigrants would affect the country’s “absorptive capacity.”

During World War I, the Jewish population in Palestine declined because of the war, famine, disease, and expulsion by the Turks. In 1915, approximately 83,000 Jews lived in Palestine among 590,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs. According to the 1922 census, the Jewish population was 83,000, while the Arabs numbered 643,000.[4] Thus, the Arab population grew exponentially while that of the Jews stagnated.

In the mid-1920s, Jewish immigration to Palestine increased primarily because of anti-Jewish economic legislation in Poland and Washington’s imposition of restrictive quotas.[5]

The record number of immigrants in 1935 (see table) was a response to the growing persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. The British administration considered this number too large, however, so the Jewish Agency was informed that less than one-third of the quota it asked for would be approved in 1936.[6]

The British gave in further to Arab demands by announcing in the 1939 White Paper that an independent Arab state would be created within ten years and that Jewish immigration was to be limited to 75,000 for the next five years, after which it was to cease altogether. It also forbade land sales to Jews in 95% of the territory of Palestine. The Arabs, nevertheless, rejected the proposal.

Jewish Immigration to Palestine[7]

|

1919 |

1,806 |

1931 |

4,075 |

|

1920 |

8,223 |

1932 |

12,533 |

|

1921 |

8,294 |

1933 |

37,337 |

|

1922 |

8,685 |

1934 |

45,267 |

|

1923 |

8,175 |

1935 |

66,472 |

|

1924 |

13,892 |

1936 |

29,595 |

|

1925 |

34,386 |

1937 |

10,629 |

|

1926 |

13,855 |

1938 |

14,675 |

|

1927 |

3,034 |

1939 |

31,195 |

|

1928 |

2,178 |

1940 |

10,643 |

|

1929 |

5,249 |

1941 |

4,592 |

|

1930 |

4,944 |

By contrast, throughout the Mandatory period, Arab immigration was unrestricted. In 1930, the Hope Simpson Commission, sent from London to investigate the 1929 Arab riots, said the British practice of ignoring the uncontrolled illegal Arab immigration from Egypt, Transjordan, and Syria had the effect of displacing the prospective Jewish immigrants.[8]

The British governor of the Sinai from 1922 to 1936 observed, “This illegal immigration was not only going on from the Sinai, but also from Transjordan and Syria, and it is very difficult to make a case out for the misery of the Arabs if at the same time their compatriots from adjoining states could not be kept from going in to share that misery.”[9]

The Peel Commission reported in 1937 that the “shortfall of land is…due less to the amount of land acquired by Jews than to the increase in the Arab population.”[10]

The British changed their policy to allow Holocaust survivors to settle in Palestine.

FACT

The gates of Palestine remained closed for the duration of the war, stranding hundreds of thousands of Jews in Europe, many of whom became victims of Hitler’s “Final Solution.” After the war, the British refused to allow the survivors of the Nazi nightmare to find sanctuary in Palestine. On June 6, 1946, President Truman urged the British government to relieve the suffering of the Jews confined to displaced persons camps in Europe by immediately accepting 100,000 Jewish immigrants. Britain’s foreign minister Ernest Bevin replied sarcastically that the United States wanted displaced Jews to immigrate to Palestine “because they did not want too many of them in New York.”[11]

Some Jews reached Palestine, many smuggled in on dilapidated ships organized by the Haganah. Between August 1945 and the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, sixty-five “illegal” immigrant ships, carrying 69,878 people, arrived from European shores. In August 1946, however, the British began to intern those they caught in camps on Cyprus. Approximately 50,000 people were detained in the camps, and 28,000 remained imprisoned when Israel declared independence.[12]

As the Jewish population grew, the plight of the Palestinian Arabs worsened.

FACT

In July 1921, Hasan Shukri, the mayor of Haifa and president of the Muslim National Associations, sent a telegram to the British government in reaction to a delegation of Palestinians that went to London to try to stop the implementation of the Balfour Declaration. Shukri wrote:

The Jewish population increased by 470,000 between World War I and World War II, while the non-Jewish population rose by 588,000.[14] The permanent Arab population increased by 120% between 1922 and 1947.[15]

This rapid growth of the Arab population was a result of several factors. One was immigration from neighboring states—constituting 37% of the total immigration to pre-state Israel—by Arabs who wanted to take advantage of the higher standard of living the Jews had made possible.[16] The Arab population also grew because of the improved living conditions created by the Jews as they drained malarial swamps and brought improved sanitation and health care to the region. Thus, for example, the Muslim infant mortality rate fell from 201 per thousand in 1925 to 94 per thousand in 1945, and life expectancy rose from 37 years in 1926 to 49 in 1943.[17]

The Arab population increased the most in cities where large Jewish populations had created new economic opportunities. From 1922–1947, the non-Jewish population increased by 290% in Haifa, 131% in Jerusalem, and 158% in Jaffa. The growth in Arab towns was more modest: 42% in Nablus, 78% in Jenin, and 37% in Bethlehem.[18]

Jews stole Arab land.

FACT

Despite the growth in their population, the Arabs continued to assert they were being displaced. From the beginning of World War I, however, part of Palestine’s land was owned by absentee landlords who lived in Cairo, Damascus, and Beirut. About 80% of the Palestinian Arabs were debt-ridden peasants, semi-nomads, and Bedouins.[19]

Jews went out of their way to avoid purchasing land in areas where Arabs might be displaced. They sought land that was largely uncultivated, swampy, cheap, and—most important—without tenants. In 1920, Labor Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion expressed his concern about the Arab fellahin, whom he viewed as “the most important asset of the native population.” He insisted that “under no circumstances must we touch land belonging to fellahs or worked by them.” Instead, he advocated helping liberate them from their oppressors. “Only if a fellah leaves his place of settlement,” Ben-Gurion added, “should we offer to buy his land, at an appropriate price.”[20]

Jews only began to purchase cultivated land after buying all the uncultivated territory. Many Arabs were willing to sell because of the migration to coastal towns and because they needed money to invest in the citrus industry.[21]

When John Hope Simpson arrived in Palestine in May 1930, he observed, “They [the Jews] paid high prices for the land and, in addition, they paid to certain of the occupants of those lands a considerable amount of money which they were not legally bound to pay.”[22]

In 1931, Lewis French conducted a survey of landlessness for the British government and offered new plots to any Arabs who had been “dispossessed.” British officials received more than 3,000 applications, of which 80% were ruled invalid by the government’s legal adviser because the applicants were not landless Arabs. This left only about 600 landless Arabs, 100 of whom accepted the government land offer.[23]

In April 1936, a new outbreak of Arab attacks on Jews was instigated by local Palestinian leaders who were later joined by Arab volunteers led by a Syrian guerrilla named Fawzi al-Qawuqji, the commander of the Arab Liberation Army. By November, when the British finally sent a new commission headed by Lord Peel to investigate, 89 Jews had been killed and more than 300 wounded.[24]

The Peel Commission’s report found that Arab complaints about Jewish land acquisition were baseless. It pointed out that “much of the land now carrying orange groves was sand dunes or swamp and uncultivated when it was purchased…[T]here was at the time of the earlier sales little evidence that the owners possessed either the resources or training needed to develop the land.”[25] Moreover, the Commission found the shortage was “due less to the amount of land acquired by Jews than to the increase in the Arab population.” The report concluded that the presence of Jews in Palestine, along with the work of the British administration, had resulted in higher wages, an improved standard of living, and ample employment opportunities.[26]

|

It is made quite clear to all, both by the map drawn up by the Simpson Commission and by another compiled by the Peel Commission, that the Arabs are as prodigal in selling their land as they are in useless wailing and weeping (emphasis in the original). —Transjordan’s king Abdullah[27] |

Even at the height of the Arab revolt in 1938 (which began in April 1936 with the murder of two Jews by Arabs and the subsequent murder of two Arab workers by members of the Jewish underground[28]), the British high commissioner to Palestine believed the Arab landowners were complaining about sales to Jews to drive up prices for lands they wished to sell. Many Arab landowners had been so terrorized by Arab rebels they decided to leave Palestine and sell their property to the Jews.[29]

The Jews paid exorbitant prices to wealthy landowners for small tracts of arid land. “In 1944, Jews paid between $1,000 and $1,100 per acre in Palestine, mostly for arid or semiarid land; in the same year, rich black soil in Iowa was selling for about $110 per acre.”[30]

By 1947, Jewish holdings in Palestine amounted to about 463,000 acres. Approximately 45,000 were acquired from the mandatory government, 30,000 were bought from various churches, and 387,500 were purchased from Arabs. Analyses of land purchases from 1880 to 1948 show that 73% of Jewish plots were purchased from large landowners, not poor fellahin.[31] Many leaders of the Arab nationalist movement, including members of the Muslim Supreme Council, and the mayors of Gaza, Jerusalem, and s sold land to the Jews. As’ad el-Shuqeiri, a Muslim religious scholar and father of Palestine Liberation Organization chairman Ahmed Shuqeiri, took Jewish money for his land. Even King Abdullah leased land to the Jews.[32]

The British helped the Palestinians to live peacefully with the Jews.

FACT

In 1921, Haj Amin el-Husseini first began to organize fedayeen (“one who sacrifices himself”) to terrorize Jews. El-Husseini hoped to duplicate the success of Kemal Atatürk in Turkey by driving the Jews out of Palestine just as Kemal had driven the invading Greeks from his country.[33] Arab radicals gained influence because the British administration was unwilling to take effective action against them until they began a revolt against British rule.

Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, former head of British military intelligence in Cairo, and later chief political officer for Palestine and Syria, wrote in his diary that British officials “incline towards the exclusion of Zionism in Palestine.” The British encouraged the Palestinians to attack the Jews. According to Meinertzhagen, Col. Bertie Harry Waters-Taylor (financial adviser to the military administration in Palestine 1919–23) met with el-Husseini in 1920, a few days before Easter, and told him that “he had a great opportunity at Easter to show the world…that Zionism was unpopular not only with the Palestine administration but in Whitehall.” He added that “if disturbances of sufficient violence occurred in Jerusalem at Easter, both General [Louis] Bols [chief administrator in Palestine, 1919–20] and General [Edmund] Allenby [commander of the Egyptian force, 1917–19, then high commissioner of Egypt] would advocate the abandonment of the Jewish Home. Waters-Taylor explained that freedom could only be attained through violence.”[34]

El-Husseini took the colonel’s advice and instigated a riot. The British withdrew their troops and the Jewish police from Jerusalem, allowing the Arab mob to attack Jews and loot their shops. Because of el-Husseini’s overt role in instigating the pogrom, the British decided to arrest him. He escaped, however, and was sentenced to ten years in absentia.

A year later, some British Arabists convinced High Commissioner Herbert Samuel to pardon el-Husseini and to appoint him Mufti (a cleric in charge of Jerusalem’s Islamic holy places). By contrast, Vladimir Jabotinsky and several followers, who had formed a Jewish defense organization during the unrest, were sentenced to 15 years. They were released a few months later.[35]

Samuel met with el-Husseini on April 11, 1921, and was assured “that the influences of his family and himself would be devoted to tranquility.” Three weeks later, riots in Jaffa and elsewhere left forty-three Jews dead.[36]

El-Husseini consolidated his power and took control of all Muslim religious funds in Palestine. He used his authority to gain control over the mosques, the schools, and the courts. No Arab could reach an influential position without being loyal to the Mufti. His power was so absolute that “no Muslim in Palestine could be born or die without being beholden to Haj Amin.”[37] The Mufti’s henchmen also ensured he would have no opposition by systematically killing Palestinians who discussed cooperation with the Jews from rival clans.

As the spokesman for Palestinian Arabs, el-Husseini did not ask that Britain grant them independence. On the contrary, in a letter to Churchill in 1921, he demanded that Palestine be reunited with Syria and Transjordan.[38]

The Arabs found rioting an effective political tool because of the lax British response toward violence against Jews. In handling each riot, the British prevented Jews from protecting themselves but made little effort to prevent the Arabs from attacking them. After each outbreak, a British commission of inquiry would try to establish the cause of the violence. The conclusion was always the same: The Arabs feared being displaced by the Jews. To stop the rioting, the commissions would recommend that restrictions be placed on Jewish immigration. Thus, the Arabs learned they could always stop the influx of Jews by staging riots.

This cycle began after a series of riots in May 1921. After failing to protect the Jewish community from Arab mobs, the British appointed the Haycraft Commission to investigate the cause of the violence. Although the panel concluded the Arabs had been the aggressors, it rationalized the cause of the attack: “The fundamental cause of the riots was a feeling among the Arabs of discontent with, and hostility to, the Jews, due to political and economic causes, and connected with Jewish immigration, and with their conception of Zionist policy.”[39] One consequence of the violence was the institution of a temporary ban on Jewish immigration.

The Arab fear of being “displaced” or “dominated” was an excuse for their attacks on Jewish settlers. Note, too, that these riots were not inspired by nationalistic fervor—nationalists would have rebelled against their British overlords—they were motivated by economics, the radical Islamic views of the Mufti, and misunderstanding.

In 1929, Arab provocateurs convinced the masses that the Jews had designs on the Temple Mount (a tactic still used today to incite violence). A Jewish religious observance at the Western Wall, which forms a part of the Temple Mount, served as a pretext for rioting by Arabs against Jews, which spilled out of Jerusalem into other villages and towns, including Safed and Hebron.

Again, the British administration made no effort to prevent the violence, and, after it began, the British did nothing to protect the Jewish population. After six days of mayhem, the British finally brought troops in to quell the disturbance. By this time, most of Hebron’s Jews had fled or been killed. In all, 133 Jews were killed and 399 wounded in the pogroms.[40]

After the riots, the British ordered an investigation, resulting in the Passfield White Paper. It said the “immigration, land purchase and settlement policies of the Zionist Organization were already or were likely to become, prejudicial to Arab interests. It understood the mandatory government’s obligation to the non-Jewish community to mean that Palestine’s resources must be primarily reserved for the growing Arab economy.”[41] This meant it was necessary to restrict Jewish immigration and land purchases.

The Mufti was not a Nazi collaborator.

FACT

In 1941, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, fled to Germany and met with Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, Joachim Von Ribbentrop, and other Nazi leaders. He wanted to persuade them to extend the Nazis’ anti-Jewish program to the Arab world.

The Mufti sent Hitler fifteen drafts of declarations he wanted Germany and Italy to make concerning the Middle East. One called on the two countries to declare the illegality of the Jewish home in Palestine. He also asked the Axis powers to “accord to Palestine and to other Arab countries the right to solve the problem of the Jewish elements in Palestine and other Arab countries in accordance with the interest of the Arabs, and by the same method that the question is now being settled in the Axis countries.”[42]

In November 1941, the Mufti met with Hitler, who told him the Jews were his foremost enemy. The Nazi dictator rebuffed the Mufti’s requests for a declaration in support of the Arabs, however, telling him the time was not right. The Mufti offered Hitler his “thanks for the sympathy which he had always shown for the Arab and especially Palestinian cause, and to which he had given clear expression in his public speeches.” He added, “The Arabs were Germany’s natural friends because they had the same enemies as had Germany, namely…the Jews.” Hitler told the Mufti he opposed the creation of a Jewish state and that Germany’s objective was destroying the Jewish element in the Arab sphere.[43]

In 1945, Yugoslavia sought to indict the Mufti as a war criminal for his role in recruiting twenty thousand Muslim volunteers for the SS, who participated in the killing of Jews in Croatia and Hungary. He escaped French detention in 1946, however, and continued his fight against the Jews from Cairo and later Beirut where he died in 1974.

The bombing of the King David Hotel was part of a deliberate terror campaign against civilians.

FACT

British troops seized the Jewish Agency compound on June 29, 1946, and confiscated large quantities of documents. At about the same time, more than 2,500 Jews from all over Palestine were arrested. A week later, news of a massacre of 40 Jews in a pogrom in Poland reminded the Jews of Palestine how Britain’s restrictive immigration policy had condemned thousands to death.

In response to the British provocations, and a desire to demonstrate that the Jews’ spirit could not be broken, the United Resistance Movement planned to bomb the King David Hotel, which housed the British military command and the Criminal Investigation Division in addition to hotel guests. The Haganah pulled out of the plot and left it up to the Irgun.

Irgun leader Menachem Begin stressed his desire to avoid civilian casualties and the plan was to warn the British so they would evacuate the building before it was blown up. Three telephone calls were placed on July 22, 1946, one to the hotel, another to the French Consulate, and a third to the Palestine Post warning that explosives in the King David Hotel would soon be detonated.

The call to the hotel was received and ignored. Begin quotes one British official who supposedly refused to evacuate the building, saying, “We don’t take orders from the Jews.”[44] As a result, when the bombs exploded, the casualty toll was high: 91 killed and 45 injured. Among the casualties were 15 Jews. Few people in the main part of the hotel were injured.[45]

For decades, the British denied they had been warned. In 1979, however, a member of the British Parliament provided the testimony of a British officer who heard other officers in the King David Hotel bar joking about a Zionist threat to the headquarters. The officer who overheard the conversation immediately left the hotel and survived.[46]

In contrast to Arab attacks against Jews, which Arab leaders hailed as heroic actions, the Jewish National Council denounced the bombing of the King David.[47]

[1] Aharon Cohen, Israel and the Arab World, (NY: Funk and Wagnalls, 1970), p. 172; Howard Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), p. 146.

[2] Moshe Aumann, “Land Ownership in Palestine 1880–1948,” in Michael Curtis, et al., The Palestinians, (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1975), p. 25.

[3] Palestine Royal Commission Report (the Peel Report), (London: 1937), p. 300. Henceforth, Palestine Royal Commission Report.

[4] Arieh Avneri, The Claim of Dispossession, (Tel Aviv: Hidekel Press, 1984), p. 28; Yehoshua Porath, The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement, 1918–1929, (London: Frank Cass, 1974), pp. 17–18.

[5] Porath (1974), p. 18.

[6] Aharon Cohen, p. 53.

[7] Yehoshua Porath, Palestinian Arab National Movement, 1929–1939: From Riots to Rebellion, vol. 2 (London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd., 1977), pp. 17–18, 39.

[8] John Hope Simpson, Palestine: Report on Immigration, Land Settlement and Development, (London, 1930), p. 126.

[9] C. S. Jarvis, “Palestine,” United Empire (London), vol. 28 (1937), p. 633.

[10] Palestine Royal Commission Report, p. 242.

[11] George Lenczowski, American Presidents and the Middle East, (NC: Duke University Press, 1990), p. 23.

[12] Aharon Cohen, p. 174.

[13] Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), p. 15.

[14] Dov Friedlander and Calvin Goldscheider, The Population of Israel, (NY: Columbia Press, 1979), p. 30.

[15] Avneri, p. 254.

[16] Curtis, p. 38.

[17] Avneri, p. 264; Cohen, p. 60.

[18] Avneri, pp. 254–55.

[19] Moshe Aumann, Land Ownership in Palestine, 1880–1948, (Jerusalem: Academic Committee on the Middle East, 1976), pp. 8–9.

[20] Shabtai Teveth, Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs: From Peace to War, (London: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 32.

[21] Porath, 80, 84; See also Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917–1948, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

[22] Hope Simpson Report, p. 51.

[23] Avneri, pp. 149–158; Cohen, p. 37; based on the Report on Agricultural Development and Land Settlement in Palestine by Lewis French (December 1931, Supplementary; Report, April 1932) and material submitted to the Palestine Royal Commission.

[24] Netanel Lorch, One Long War, (Jerusalem: Keter, 1976), p. 27; Sachar, p. 201.

[25] Palestine Royal Commission Report (1937), p. 242.

[26] Palestine Royal Commission (1937), pp. 241–42.

[27] King Abdallah, My Memoirs Completed, (London, Longman Group, Ltd., 1978), pp. 88–89.

[28] Porath (77), pp. 86–87.

[29] Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), p. 95.

[30] Aumann, p. 13.

[31] Abraham Granott, The Land System in Palestine, (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1952), p. 278.

[32] Avneri, pp. 179–180, 224–25, 232–34; Porath (77), pp. 72–73; See also Hillel Cohen, Army of Shadows.

[33] Jon Kimche, There Could Have Been Peace: The Untold Story of Why We Failed with Palestine and Again with Israel, (England: Dial Press, 1973), p. 189.

[34] Richard Meinertzhagen, Middle East Diary 1917–1956, (London: The Cresset Press, 1959), pp. 49, 82, 97.

[35] Samuel Katz, Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine, (NY: Bantam Books, 1977), pp. 63–65; Howard Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), p. 97.

[36] Paul Johnson, Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties, (NY: Harper & Row, 1983), p. 438.

[37] Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, O Jerusalem! (NY: Simon and Schuster, 1972), p. 52.

[38] Kimche, p. 211.

[39] Ben Halpern, The Idea of a Jewish State, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969), p. 323.

[40] Sachar, p. 174.

[41] Halpern, p. 201.

[42] “Grand Mufti Plotted to Do Away with All Jews in Mideast,” Response (Fall 1991), pp. 2–3.

[43] Record of the Conversation between the Führer and the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem on November 28, 1941, in the Presence of Reich Foreign Minister and Minister Grobba in Berlin, Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918–1945, Series D, Vol. XIII, London, 1964, 881ff in Walter Lacquer and Barry Rubin, The Israel-Arab Reader, (NY: Penguin Books, 2001), pp. 51–55.

[44] Menachem Begin, The Revolt, (NY: Nash Publishing, 1977), p. 224.

[45] J. Bowyer Bell, Terror Out of Zion, (NY: St. Martin’s Press), p. 172.

[46] Benjamin Netanyahu, ed., “International Terrorism: Challenge and Response,” Proceedings of the Jerusalem Conference on International Terrorism, July 2–5, 1979, (Jerusalem: The Jonathan Institute, 1980), p. 45.

[47] Anne Sinai and I. Robert Sinai, Israel and the Arabs: Prelude to the Jewish State, (NY: Facts on File, 1972), p. 83.