U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians: FY 2018

The Trump administration announced on August 24, 2018, that it would not spend more than $200 million set aside for Palestinian refugee aid (New York Times, August 24, 2018). In September, the administration said it was also cutting $25 million originally planned for the East Jerusalem Hospital Network (Reuters, September 20, 2018)) and $10 million from a program for people-to-people exchanges between Palestinians and Israelis (New York Times, September 14, 2018). In October, the State Department cancelled a $165 million transfer of aid to the Palestinian Authority over its failure to adhere to the Taylor Force Act (Jerusalem Post, October 11, 2018).

Overview and Recent Changes

Aid Limitations or Holds

Types of Bilateral aid to the Palestinians

US Contributions to UNRWA

Issues for Congress

Reduced 2018 Contributions and Future Questions

Addendum

Read Full Congressional Report - CLICK HERE

Overview and Recent Changes

Under the Obama and Trump Administrations, the executive branch and Congress have taken significant measures to reduce and delay U.S. aid to the Palestinians. Questions surround the future of this aid as policymakers try to evaluate whether it is effective in accomplishing its specific programmatic purposes, as well as in improving regional stability and U.S. political influence. Some observers, including Israelis, express concern about various aspects of the aid while also voicing caution that more major changes could affect stability and Israeli security.

Reductions and delays in aid appear to have come partly from U.S.-Palestinian political tension connected with the Trump Administration’s policy on Jerusalem. Additionally, in March 2018 Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141). This law augments existing legislative provisions to suspend U.S. bilateral economic assistance for the Palestinian Authority (PA) unless and until Palestinian officials cease certain payments deemed under U.S. law to be “for acts of terrorism.”

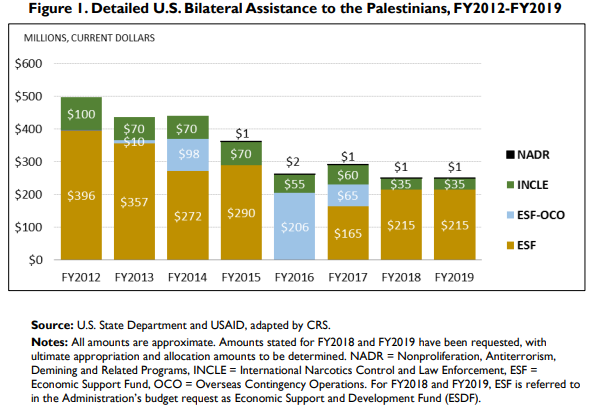

After a split between the Fatah-led PA in the West Bank and Hamas in the Gaza Strip in 2007, Congress increased bilateral economic assistance to the Palestinians (that had begun in the mid 1990s) and also began providing nonlethal security assistance. This aid has gone toward security, economic development, self-governance, and humanitarian needs—with a specific focus on boosting the PA vis-à-vis Hamas. Economic assistance includes both USAID-administered projects and payments to PA creditors. However, since FY2013, bilateral aid levels have steadily declined from their previous annual averages of $400 million (economic) and $100 million (security). The Administration’s FY2019 request is for $215 million (economic) and $35 million (security). Moreover, the Administration has not obligated any FY2017- or FY2018-appropriated bilateral economic assistance for the Palestinians to date.

Additionally, U.S. contributions to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA)—coming from global humanitarian accounts—help meet the needs of approximately 5.4 million Palestinian refugees. U.S. contributions had markedly increased over the past decade, owing largely to conflict-related humanitarian needs—particularly in Gaza and Syria. U.S. contributions for FY2017 totaled $359.3 million. To date, U.S. contributions for FY2018 have totaled $65 million, as the Administration withheld part of an expected January 2018 contribution. Given UNRWA’s dependence on voluntary donations, funding for the organization’s main activities through 2018 is in question, and partly hinges on other countries’ contributions. UNRWA’s funding concerns have influenced the ongoing U.S. public debate about the benefits and costs of the organization’s activities, and about the nexus between political issues and humanitarian assistance.

U.S. aid to the Palestinians remains subject to several legislative conditions and robust oversight from Congress. Bilateral assistance since 1994 has totaled more than $5 billion, and contributions to UNRWA since 1950 have totaled more than $6 billion.

At various points during this decade (see “Aid Limitations or Holds”), the executive branch and Congress have taken various measures to reduce or delay U.S. aid to the Palestinians, and developments to date in 2018 may increase the impact of these changes. Recent U.S. measures seem intended to prevent the Palestinians from taking actions or using aid contrary to U.S. or Israeli policies. Current concerns include

- U.S.-Palestinian political tension. The Palestinian and international response to President Trump’s December 2017 announcements on Jerusalem policy may have contributed to Trump Administration actions in early 2018 to reduce or delay aid to the Palestinians (see “U.S.-Palestinian Political Tension” below).

- Certain payments deemed under U.S. law to be “for acts of terrorism”. These are payments by Palestinian governing entities to individuals imprisoned for or killed while allegedly committing acts of terrorism, or to these individuals’ families. To discourage such payments by placing conditions on U.S. economic aid, Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, or P.L. 115-141) in March 2018 alongside other provisions on the same subject that have appeared in annual appropriations legislation on the subject since FY2015.

Significant bilateral U.S. aid to the Palestinians began when the Palestinians achieved limited self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the mid-1990s. U.S. aid for Palestinians took its current form after contention between competing factions in 2007 led to divided rule—with Fatah holding sway in the West Bank (under supervening Israeli military control) and Hamas controlling Gaza. Since 1950, additional U.S. aid for Palestinian refugees has been channeled via contributions from global humanitarian assistance accounts to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Bilateral aid to the Palestinians since 1994 has totaled more than $5 billion, and contributions to UNRWA since 1950 more than $6 billion.

In addition to meeting the Palestinians’ humanitarian needs, U.S. assistance is intended to help the Palestinians with security, economic development, and self-governance—with an emphasis on strengthening the West Bank-based, Fatah-led Palestinian Authority (PA) vis-à-vis Hamas. From FY2008 through FY2012, typical annual Economic Support Fund (ESF) assistance to the West Bank and Gaza Strip—divided between various projects and budget support for the PA (see “Types of Bilateral Aid” below)—was around $400 million. For the same period, typical annual International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) nonlethal assistance for PA security forces and the criminal justice sector in the West Bank was around $100 million. In line with Obama and Trump Administration requests, baseline funding levels for economic assistance and INCLE have declined since FY2013. Requested annual assistance amounts for FY2019 are $215 million for Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) and $35 million for INCLE.

|

The following questions may help in evaluating the effectiveness of U.S. assistance to the Palestinians:

- How does assistance affect U.S. influence with Palestinians?

- How does it address security, development, governance, and humanitarian needs?

Effectiveness can be challenged by the shifting and often conflicting objectives of Israel and various Palestinian groups. For example, Israeli security requirements or Palestinian factional disputes could affect the viability of aid programs to help with Palestinian security, infrastructure, or economic development. Additional complications come from coordinating U.S. actions with the activities of other donor states and international organizations such as the European Union (EU), United Nations, World Bank, the Office of the Quartet Representative,4 and the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee.

Aid Limitations or Holds

Since 2011, the Palestinians have faced reprisals from the United States and Israel for actions that go against U.S. or Israeli positions. Such actions include international initiatives aimed at giving Palestinians more leverage against Israel. Past reprisals included informal congressional holds that delayed disbursement of U.S. aid, and temporary Israeli refusals to transfer tax and customs revenues due the PA. Since FY2015, legislative provisions regarding Palestinian terrorismrelated payments (see “Taylor Force Act and Payments” below) have reduced economic aid for the PA.

The United States and Israel have historically shown reluctance to drastically change aid levels at least partly because of the connections their leaders cite between aid programs and stability. In a January 2018 column, former U.S. Ambassador to Israel Dan Shapiro said:

[Israeli officials] appreciate the use of assistance as leverage on the Palestinians to change their ways. But at the end of the day, they have generally calculated that [providing] the aid serves Israeli interests as well. It supports the Palestinian security forces that cooperate professionally with Israel’s own to prevent terrorist attacks. Without that support, Israel would have to spend more time addressing humanitarian suffering and spend more money to pay the bills to Israeli hospitals and electricity providers doing work for Palestinians that otherwise would go unpaid. Without this aid, stability in Palestinian society would diminish, which would also compromise Israel's security.

U.S.-Palestinian Political Tension

President Trump has hinted that continued aid to the Palestinians might depend on Palestinian willingness to participate in U.S.-mediated peace initiatives with Israel. A few days after Vice President Pence visited Israel in January 2018, the President said:

The President’s remarks reflected heightened U.S.-Palestinian tensions. In December 2017, he recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and announced his intention to relocate the U.S. embassy there from Tel Aviv. Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman and PA President Mahmoud Abbas strongly objected to the new U.S. policy, as did many other countries. This opposition was evident in December action at the United Nations. Citing alleged U.S. bias favoring Israel, Palestinian leaders are seeking to counteract U.S. influence on the peace process by increasing the involvement of other actors like the European Union and Russia. Some reports indicate, however, that the Palestinians are open to potential confidence-building measures from U.S. officials that could be communicated through other Arab states. The future course of U.S.- Palestinian relations could further affect Administration and congressional attitudes toward Palestinian aid.

It is unclear if President Trump’s stated conditions on aid apply only to bilateral assistance to the West Bank and Gaza, or also to U.S. contributions to UNRWA. The Administration has not obligated any FY2017- or FY2018-appropriated bilateral economic assistance (ESF) for the Palestinians to date. As described below, in January 2018 the Administration withheld part of an anticipated contribution to UNRWA.

Taylor Force Act and Payments “for Acts of Terrorism”

Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141) in March 2018 to alter restrictions on aid in annual appropriations legislation that date from FY2015 and are used to discourage certain PLO/PA payments “for acts of terrorism.” The PLO/PA makes payments to some Palestinians (and/or their families) imprisoned for or accused of terrorism by Israel. Because money is fungible, and the United States has regularly helped to defray PA debts, critics have asserted that any aid directly benefitting the PA could indirectly support such payments. In June 2017 testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said, “Attaching payments as recognition of violence or murders is something the American people could never accept or understand.” A March 2018 media article stated that Palestinians acknowledge some payments go to people who make “heinous attacks” or their families. However, the same article also said, “There is no standard definition for terrorism in the U.S. government, a problem State Department officials encountered when they sought to penalize the PA [under the provisions dating from FY2015]. Indeed, Palestinians may be jailed by Israel as security threats for acts that some—or many—Americans might consider civil disobedience.”

The Taylor Force Act suspends all ESF aid that “directly benefits” the PA (with specific exceptions for the East Jerusalem Hospital Network and a certain amount for wastewater projects and vaccination programs) unless and until the Administration certifies that the PA and PLO:

- are taking credible steps to end acts of violence against Israeli citizens and U.S. citizens that are perpetrated or materially assisted by individuals under their jurisdictional control, such as the March 2016 attack that killed former U.S. Army officer Taylor Force, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan;

- have terminated payments for acts of terrorism against Israeli citizens and U.S. citizens to any individual, after being fairly tried, who has been imprisoned for such acts of terrorism and to any individual who died committing such acts of terrorism, including to a family member of such individuals;

- have revoked any law, decree, regulation, or document authorizing or implementing a system of compensation for imprisoned individuals that uses the sentence or period of incarceration of an individual imprisoned for an act of terrorism to determine the level of compensation paid, or have taken comparable action that has the effect of invalidating any such law, decree, regulation, or document; and

- are publicly condemning such acts of violence and are taking steps to investigate or are cooperating in investigations of such acts to bring the perpetrators to justice.

If the Administration cannot certify that the PA and PLO have taken these steps, the Administration is required to report to Congress on the reasons for its failure to certify, the definition of “acts of terrorism” that it used, and the amount of aid to be withheld. Separately, the Act requires the Administration to submit to Congress an updated list of the criteria it uses to determine which assistance “directly benefits” the PA, given that questions persist about how broadly this term might apply to certain kinds of development and humanitarian assistance. Additionally, for six years the Administration must submit an annual report to Congress providing estimates of PLO/PA terrorism-related payments, along with information related to the Palestinian legal basis for the payments and to U.S. efforts toward the goal of ending the PLO/PA payments and removing any such legal basis.

The Taylor Force Act also contains a mechanism by which the withheld aid can be used to directly benefit the PA if the Administration makes the certification described above within a certain time period. However, after that time period expires, 50% of the withheld aid can be used for purposes that do not directly benefit the PA, and 50% can only be used outside of the West Bank and Gaza.

As referenced above, since FY2015, annual appropriations legislation (including Section 7041(m)(3) of P.L. 115-141) has provided for “dollar-for-dollar” reduction of ESF aid for the PA in relation to PLO/PA terrorism-related payments. ESF amounts withheld under the Taylor Force Act need to be at least what is required under the dollar-for-dollar reduction provision, and will be deemed to satisfy that provision.

While Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu praised the enactment of the Taylor Force Act, the PLO representative to the United States, Husam Zomlot, denounced it as flagrantly biased and deliberately aimed at the Palestinian people. It is unclear whether the Act will significantly affect PLO/PA terrorism-related payments, though a recent media report suggested that Palestinian officials do not plan to stop them.

Other Conditions on Aid

In addition to the provisions discussed above, annual appropriations legislation routinely contains the following selected conditions on U.S. aid to Palestinians:

- Hamas and terrorism. Aid to Hamas or Hamas-controlled entities is specifically prohibited, and no aid may be made available for the purpose of recognizing or otherwise honoring individuals who commit or have committed acts of terrorism. Additionally, the Secretary of State is required to take all appropriate steps to ensure that economic assistance for the West Bank and Gaza does not support terrorism, and to terminate assistance to “any individual, entity, or educational institution which the Secretary has determined to be involved in or advocating terrorist activity.”

- Fatah-Hamas “unity” government scenario. Generally, no aid is permitted for a power-sharing PA government that includes Hamas as a member, or that results from an agreement with Hamas and over which Hamas exercises “undue influence.” This general restriction is only lifted if the President certifies that the PA government, including all ministers, has “publicly accepted and is complying with” the following two principles embodied in Section 620K of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended by the Palestinian Anti-Terrorism Act of 2006 (PATA, P.L. 109-446): (1) recognition of “the Jewish state of Israel’s right to exist” and (2) acceptance of previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements (the “Section 620K principles”). If the PA government is “Hamas-controlled,” PATA applies additional conditions, limitations, and restrictions on aid.

- International Criminal Court action. ESF assistance for the PA is prohibited if “the Palestinians initiate an International Criminal Court judicially authorized investigation, or actively support such an investigation, that subjects Israeli nationals to an investigation for alleged crimes against Palestinians.”

- Membership in the United Nations or U.N. agencies. ESF assistance for the PA is prohibited if the Palestinians obtain “the same standing as member states or full membership as a state outside an agreement negotiated between Israel and the Palestinians” in the United Nations or any U.N. specialized agency other than U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- PA personnel in Gaza. No aid is permitted for PA personnel located in Gaza.

- PLO and Palestinian Broadcasting Corporation (PBC). No aid is permitted for the PLO or for the PBC.

- Palestinian state. No funds may be provided to support a future Palestinian state unless the Secretary of State certifies that the governing entity of the state has committed to peaceful coexistence with Israel, is taking measures to counter terrorism, and is working to establish “comprehensive peace in the Middle East.” This restriction can be waived for national security purposes, and does not apply to aid meant to reform the Palestinian governing entity so that it might meet the these conditions.

- Vetting, monitoring, and evaluation. For U.S. aid programs for the Palestinians, annual appropriations legislation routinely requires executive branch reports and certifications, as well as internal and Government Accountability Office (GAO) audits. These requirements appear to be aimed at, among other things, preventing U.S. aid from benefitting terrorists or abetting corruption, and assessing aid programs’ effectiveness. This vetting process has become more rigorous since 2006 in response to recommendations from GAO. In April 2016, a GAO report found that USAID had generally complied with vetting requirements since the 2006 changes.

Types of U.S. Bilateral aid to the Palestinians

Project Assistance

Most economic aid to the Palestinians is appropriated through the ESF account and provided by USAID and other government agencies to implementing partners (both for-profit and nonprofit grantees) operating in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Funds are allocated in this program for projects in sectors such as humanitarian assistance, economic development, democratic reform, improving water access and other infrastructure, health care and education. In addition to bilateral U.S. assistance to the Palestinians, some amounts generally are allocated from various foreign assistance accounts for Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation or Arab-Israeli cooperation.

The Palestinians face some serious structural economic challenges, particularly in Gaza, where real GDP growth fell from around 8% in 2016 to 0.5% in 2017 (well below the estimated population growth rate of 2.3%) . According to the World Bank, this was largely due to a “severe liquidity squeeze arising from sharply reduced reconstruction aid flows and disrupted fiscal relations with the West Bank, in addition to continued economic isolation.”

Palestinian Authority Budget Support

ESF budgetary assistance is a part of the U.S. strategy to support the PA in the West Bank. The PA’s dependence on foreign assistance is acute—largely a result of the distortion of the West Bank/Gaza economy over five decades of Israeli occupation and the bloat of the PA’s payroll since its inception nearly 25 years ago. Domestic corruption and inefficiency also appear to pose difficulties.

Facing a regular annual budget deficit of over $1 billion, PA officials have traditionally sought aid from the United States and other international sources to meet the PA’s financial commitments. Absent fundamental changes in revenue and expenses, which do not appear probable in the near term, the PA’s fiscal dependence on external sources is likely to continue.

Since FY2014, U.S. practice has been to make direct payments to PA creditors. In the Administration’s FY2018 budget request, it stated that funds would “support payments to creditors so that the Palestinian Authority can continue to provide critical services for Palestinians.” Under the Taylor Force Act, it appears that only the payments to certain East Jerusalem hospitals will continue unless and until the PLO/PA stops the payments “for acts of terrorism” identified in the Act.

U.S. Security Assistance to the Palestinian Authority

Aid from the INCLE account has been given to train, reform, advise, house, and provide nonlethal equipment for PA civil security forces in the West Bank loyal to President Abbas.

This aid is aimed at countering militants from organizations such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and establishing the rule of law for an expected Palestinian state. In recent years, some of this training and infrastructure assistance has been provided to strengthen and reform the PA criminal justice sector.

In its FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification, the State Department stated the following in support of its request for $35 million in INCLE funds for the West Bank:

Since Hamas forcibly took control of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, the office of the U.S. Security Coordinator (USSC) for Israel and the Palestinian Authority has worked in coordination with the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) to sponsor and oversee U.S.-funded training for West Bank-based PA security forces personnel, many of whom were newly recruited and vetted. Much of the training has taken place in Jordan, at least partly because of Israeli conditions on the use of firearms in the West Bank. The USSC is a three-star U.S. general/flag officer, supported as of early 2018 by U.S. and allied staff and military officers from the United Kingdom, Canada, Turkey, Italy, and the Netherlands.51 Around 2012, the USSC/INL program reportedly shifted to a less resource intensive “advise and assist” role alongside its efforts to assist the PA in improving the functioning of its criminal justice system.

The USSC/INL security assistance program exists alongside other assistance and training programs provided to Palestinian security forces and intelligence organizations by various countries and the European Union (EU). By most accounts, the PA forces receiving training have shown increased professionalism and have helped improve law and order in West Bank cities, despite continuing challenges that stem from squaring Palestinian national aspirations with coordinating security with Israel.

U.S. Contributions to the UNRWA

Overview

Since UNRWA’s inception in 1949, the United States has been the agency’s largest donor, with more than $6 billion in contributions (see Table below). UNRWA’s mandate is to “provide relief, human development and protection services to Palestine refugees and persons displaced by the 1967 hostilities in its fields of operation: Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, West Bank and the Gaza Strip.” The U.N. General Assembly continues to renew UNRWA’s mandate pending resolution of the status of “Palestine refugees”—approximately 5.4 million people who include original refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and their descendants in the places listed above. All other refugees worldwide fall under the mandate of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

UNRWA is partly shaped by the context in which it operates. Most of UNRWA’s employees— other than its senior international staff—are drawn from the Palestinian refugee population it serves. UNRWA’s website states that its role encompasses “global advocacy for Palestine refugees” in addition to the provision of assistance and protection. UNRWA does not have a robust policing capability. It often faces security concerns along with political pressures from Hamas and other actors.

U.S. contributions to UNRWA—separate from U.S. bilateral aid to the West Bank and Gaza— generally come from the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) account (including some amounts designated as MRA-Overseas Contingency Operations assistance, or MRA-OCO) and, in exceptional situations, the Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance (ERMA) account. These contributions are managed by the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM).

The program budget for UNRWA’s core programs is funded mainly by Western governments, international organizations, and private donors via voluntary contributions. Core programs include providing food, shelter, education, medical care, microfinance, and other humanitarian and social services to designated beneficiaries. UNRWA also launches emergency appeals and special funds for pressing humanitarian needs. In FY2017, the United States contributed a total of $359.3 million: $160 million to the program budget, $103.3 million to an emergency appeal for Syria, $95 million to a West Bank/Gaza emergency appeal, and around $966,000 to an antigender-based violence initiative called “Safe from the Start.

Historical U.S. Government Contributions to UNRWA

(in $ millions)

|

Fiscal Year(s) |

Amount |

Fiscal Year(s) |

Amount |

|

1950-1989 |

1,473.3 |

2004 |

127.4 |

|

1990 |

57.0 |

2005 |

108.0 |

|

1991 |

75.6 |

2006 |

137.0 |

|

1992 |

69.0 |

2007 |

154.2 |

|

1993 |

73.8 |

2008 |

184.7 |

|

1994 |

78.2 |

2009 |

268.0 |

|

1995 |

74.8 |

2010 |

237.8 |

|

1996 |

77.0 |

2011 |

249.4 |

|

1997 |

79.2 |

2012 |

233.3 |

|

1998 |

78.3 |

2013 |

294.0 |

|

1999 |

80.5 |

2014 |

398.7 |

|

2000 |

89.0 |

2015 |

390.5 |

|

2001 |

123.0 |

2016 |

359.5 |

|

2002 |

119.3 |

2017 |

359.3 |

|

2003 |

134.0 |

TOTAL |

6,183.4 |

Source: U.S. State Department

Issues for Congress

Vetting of UNRWA Contributions

Some Members of Congress raise concerns that U.S. contributions to UNRWA might be used to support terrorists. Section 301(c) of the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act (P.L. 87-195), as amended, says that “No contributions by the United States shall be made to [UNRWA] except on the condition that [UNRWA] take[s] all possible measures to assure that no part of the United States contribution shall be used to furnish assistance to any refugee who is receiving military training as a member of the so-called Palestine Liberation Army or any other guerrilla type organization or who has engaged in any act of terrorism.”

To date, no arm of the U.S. government has found UNRWA to be out of compliance with Section 301(c). For 2010 and each year thereafter, the State Department and UNRWA have had a nonbinding “Framework for Cooperation” in place. Each of the documents has agreed that, along with the compliance reports UNRWA submits to State biannually, State would use enumerated criteria as a way to evaluate UNRWA’s compliance with Section 301(c).

Legislation and Oversight

Some Members of Congress have supported legislation or resolutions aimed at increasing oversight of UNRWA, strengthening its vetting procedures, and/or capping U.S. contributions. Since FY2015, annual appropriations legislation (for FY2018, Section 7048(d) of P.L. 115-141) has included a provision requiring the State Department to report to Congress on whether UNRWA is:

- using Operations Support Officers to inspect UNRWA installations and reporting any inappropriate use;

- acting promptly to address any staff or beneficiary violations of Section 301(c) or UNRWA internal policies;

- implementing procedures to maintain its facilities’ neutrality, and conducting regular inspections;

- taking necessary and appropriate measures to ensure Section 301(c) compliance and related reporting;

- taking steps to ensure the content of educational materials taught in UNRWA administered schools and summer camps is consistent with the values of human rights, dignity, and tolerance and does not induce incitement;

- not engaging in financial violations of U.S. law, and taking steps to improve financial transparency; and

- in compliance with U.N. audit requirements.

In 2012, public debate intensified over whether UNRWA was perpetuating the refugee issue by providing services to descendants of the original Palestinian refugees from 1948. That year, the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs approved a reporting requirement in connection with FY2013 appropriations that, if enacted, would have required the Secretary of State to differentiate between the original 1948 refugees and their descendants. In a letter to the subcommittee, the State Department objected, asserting that this requirement would be “viewed around the world as the United States acting to prejudge and determine the outcome of this sensitive issue.”

Regarding this issue, UNRWA officials insisted that established “principles and practice—as well as realities on the ground—clearly refuted the argument that the right of return of Palestine refugees would disappear or be abandoned if UNHCR [the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, instead of UNRWA] were responsible for these refugees.” As part of the public debate, some observers asserted that the UNHCR definition for refugees was different from the UNRWA definition. In September 2013 correspondence with CRS on this issue, a State Department official stated:

In protracted refugee situations, refugee groups experience natural population growth over time. UNHCR and UNRWA both generally recognize descendants of refugees as refugees for purposes of their operations; this approach is not unique to the Palestinian context. For example, UNHCR recognizes descendants of refugees as refugees in populations including, but not limited to, the Burmese refugee population in Thailand, the Bhutanese refugee population in Nepal, the Afghan population in Pakistan, and the Somali population seeking refuge in neighboring countries. The United States’ acceptance of UNRWA’s method of recognizing refugees is unrelated to the final status issue of Palestinian refugees, which is to be resolved in negotiations between the parties.

Reduced 2018 Contributions and Future Questions

During FY2018, U.S. funding to UNRWA has been a subject of increased debate among U.S. policymakers. Based on the practice from previous years, it had been anticipated that a tranche of funding ($125 million) would be forthcoming in January 2018. The Administration provided some of this funding; however, it also withheld or placed conditions on selected U.S. contributions. Specifically:

- According to the State Department, the United States provided $5 million to UNRWA in early FY2018.

- In December 2017, the United States pledged $45 million to UNRWA’s West Bank and Gaza Emergency Appeal to assist UNRWA in procuring emergency food for 2018. The United States has so far not fulfilled this pledge. The State Department spokesperson stated in January 2018 that the pledge was not a guarantee, and noted that the $45 million would not be provided at the time, but “that does not mean that it will not be provided in the future;”

- On January 16, 2018, the United States provided a voluntary contribution of $60 million to UNRWA’s 2018 program budget to meet immediate cash requirements; the Administration specified that this funding would pay salaries for UNRWA’s core education and health programs;

- On January 16, the Administration also announced that it would withhold $65 million from UNRWA “for future consideration;” and

- The Administration, for the first time, placed a geographical limitation on a contribution to UNRWA, stating that the $60 million could only be used for eligible Palestine refugees registered with UNRWA in Gaza, Jordan, and the West Bank (Lebanon and Syria were not mentioned).

The Administration provided some explanation for its UNRWA funding decisions. The State Department spokesperson communicated that the Palestinians are not being punished politically, and that the Administration is focusing on UNRWA’s operations and on “asking other nations around the world, including Arab nations and others, to kick in money.” The spokesperson also noted that the Administration would like to see “some revisions” made in how UNRWA “handles itself and how it manages its money.” The spokesperson later elaborated that the Administration would like UNRWA to “develop a funding mechanism structure that is better sustaining,” citing concerns with end-of-year pleas for emergency funding.

The implications and impact of reduced U.S. contributions to UNRWA remain unclear. UNRWA’s ability to fund its main services through 2018 may depend in part on specific U.S. funding decisions and whether alternative funding sources can be secured. Congress could consider a number of options related to U.S. contributions. Total U.S. contributions to UNRWA to date for FY2018 are $65 million (compared with the $359.3 million mentioned above for FY2017). According to one April media report, “Gulf [Arab] states, Norway, Turkey and Canada have stepped in with a total of $200 million to help meet [UNRWA’s] $446 million budget deficit for 2018.”

Israeli and Palestinian officials have weighed in on the debate over U.S. funding of UNRWA. In response to the January 2018 funding decisions, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu applauded what he termed the Administration’s “challenge to UNRWA.” Some prominent Israelis have criticized of UNRWA for things such as alleged bias, perpetuation of Palestinian dependency, and enabling of Hamas. Some of these critics, however, cite humanitarian and stability considerations (especially in Gaza) to caution against sudden or total funding cutoffs that could affect UNRWA’s current capacity. Husam Zomlot, the PLO’s representative to the United States, called the U.S. decisions on UNRWA contributions “indefensible,” and said that “these actions add greater uncertainty to an already volatile situation in Palestine and in the region, and run against the core values of the US and the international system.”

Read Full Congressional Report - CLICK HERE

Addendum

In August 2018, the Trump administration released roughly $61 million in previously withheld security assistance to the Palestinian Authority to reinforce PA security cooperation with Israel. These funds are earmarked for international narcotics and law enforcement as well as non-proliferation, anti-terrorism and demining funding.

Sources: Zanotti, Jim. “U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians,” Congressional Research Service, (May 18, 2018);

Michael Wilner, “Trump Releases Some Pa Security Aid,” Jerusalem Post, (August 2, 2018).