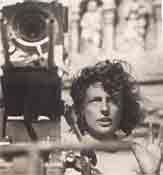

Leni Riefenstahl

(1902 - 2003)

“They kept asking me over and over again whether I was having a romance with Hitler. ‘Are you Hitler's girlfriend?’

I laughed and answered the same way each time: ‘No, those are false rumours. I only made documentaries for him...’”— Leni Riefenstahl, about her US tour in 1938, in her book A Memoir

Berlin Beginnings

She was Hitler's favorite director. She was beautiful and talented. She was a woman in a man's field.

Leni Riefenstahl (REEF-en-shtal), who remained active into her late 90s, was never able to shed the historical contamination that attached to her during the last half of her 101 years. Despite (some say because of) her demonstrated talent as actor, dancer, director, cinematographer, and still photographer, Riefenstahl could not shake off her Third Reich associations. Although her films have had enormous impact on world cinema, the woman herself found it difficult to gain public respect. Her attempt to revive her directorial career in the 1950s proved futile. The often-imitated, seldom-honored artist remained a controversial and unrepentant pariah up until her death on 8 September 2003. Ironically, her own well-crafted black-and-white motion-picture images of Hitler, Nazi pageantry, and the Jesse Owens Olympics helped keep both her genius and her past alive. In the words of Ray Müller, director of the documentary The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, “Her talent was her tragedy.”

Riefenstahl's story begins in the Wedding district of Berlin, near the start of the twentieth century. Her father, Alfred Riefenstahl, was a prosperous businessman dealing in heating and ventilation. Her mother, Bertha Sherlach, had been a part-time seamstress before she married. Their first child, Helene (Leni) Bertha Amalie Riefenstahl, was born on August 22, 1902 in the family's apartment on Prinz-Eugen-Straße in Berlin. Leni's younger brother, Heinz, was born three and a half years later. He would later die in Hitler's war at age 38 on the Russian front.

“Mountain of Destiny”

Young Leni grew up in Berlin and lived at home until she was 21. Against the wishes of her father, she studied dance and was soon performing in Munich, Berlin, and Prague. But according to her memoirs, the course of her life was changed dramatically one day as she was waiting for a subway train at the Nollendorfplatz U-Bahn station in Berlin. In a daze, thinking about the whirlwind of her dance appearances over the last six months, Riefenstahl could feel the pain in her injured knee that was threatening to end her dancing career in its early stages. She was on her way to yet another doctor, trying to find one who could finally put her back on her dancing feet. Her gaze happened to fall upon an advertising poster on the wall opposite the platform. Suddenly the image of a man climbing a jagged mountain came into focus. The colorful poster was promoting a movie with prophetic name Berg des Schicksals ("Mountain of Destiny"). Its letters further spelled out the words: “Ein Film aus den Dolomiten von Dr. Arnold Fanck” (“A film from the Dolomites by Dr. Arnold Fanck”). The picture was currently playing at a nearby cinema.

Riefenstahl stood in a trance, staring ahead blankly as her train came into the station and departed without her. Instead of going to the doctor, she left the station and soon found herself in a completely different world watching vivid, lifelike images of majestic mountains. Dr. Fanck's "Mountain of Destiny" held her so much in its spell that the young woman returned for repeat viewings every night for a week. It was the beginning of her own mountain film destiny and a new career as both film actress and director.

Amazingly, Riefenstahl appeared in her first film, Der heilige Berg (“written for the dancer Leni Riefenstahl”), directed by Dr. Arnold Fanck, only some 18 months after that fateful day at the Nollendorfplatz U-Bahn station. Within weeks of seeing Fanck's Mountain of Destiny she had happened to meet the director himself in Berlin. Following a successful operation on her knee, Riefenstahl met with Fanck at his home in Freiburg near the Black Forest. Soon she would be appearing in movies directed by Fanck and co-starring Luis Trenker. Her dream was coming true, but the day would come when she regretted having ever met either of these two men.

After appearing in several films, Riefenstahl turned to directing—remarkable for a field so dominated by men, then as now. An admirer by the name of Adolf Hitler asked her to film a documentary of his Nazi party's rally in Nuremberg, and the rest is indeed history.

Riefenstahl was put in charge of filming the 1936 Berlin Olympics, no minor undertaking. For Olympia she had to manage a total crew of 60 cinematographers. Three different types of black-and-white film stock—Agfa (architectural shots), Kodak (portraits), Perutz (fields, grass)—were used to shoot over 1.3 million feet of film (400,000 meters, over 248 miles). In the process, Riefenstahl invented or enhanced many of the sports photography techniques we now take for granted: slow motion, underwater diving shots, extremely high (from towers) and low shooting angles (from pits), panoramic aerial shots, and tracking systems for following fast action. The result is considered a classic cinematic masterpiece. Olympia premiered at Berlin's UFA Palast am Zoo cinema on Hitler's birthday, April 20, 1938.

The America Tour

In 1938 Riefenstahl embarked on a trip to America, including Hollywood, to promote Olympia. The visit was marred by several factors, not the least of which was the infamous Kristallnacht – the Nazi burning of synagogues and the vicious persecution of Jewish shopkeepers in Germany on November 9. No less disruptive for Riefenstahl's U.S. tour were the efforts of the Anti-Nazi League as well as a spy in her own entourage, one Ernst Jäger, who turned out not to be the loyal colleague Riefenstahl thought he was. Too late she would discover that it was Jäger who helped sabotage her efforts to arrange the U.S. distribution of her award-winning Olympia documentary.

For her Hollywood stay Riefenstahl booked a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Despite a hostile press and the billboard equivalent of “Leni Go Home!,” the world's most famous (or infamous) female director gained an audience with Walt Disney, although he did refuse her offer of a private showing of Olympia. He was just too afraid of a possible boycott of Disney films. Other studio heads treated her like the pariah she had become, refusing to see her at all. An invitation to meet with Gary Cooper was suddenly and “regretfully” cancelled. Even Disney would later make the unconvincing claim that he hadn't known who Riefenstahl really was.

Interrupted by war and other problems, Tiefland - 14 years in the making - premiered February 1954 in Stuttgart. It would be the last release of a motion picture directed by Leni Riefenstahl until 2002, when Riefenstahl's Impressionen unter Wasser was to be released.

However, Riefenstahl did finally manage to arrange a private screening of Olympia for an exclusive audience of some 50 press people and Hollywood insiders, some of whom felt compelled to sneak into the darkened theater incognito. Despite the Riefenstahl boycott, the press reviews for Olympia were enthusiastic. The Los Angeles Times wrote: “This picture is a triumph of the camera and an epic of the screen. Contrary to rumour, it is in no way a propaganda movie, and as propaganda for any nation, its effect is definitely zero.” Such praise notwithstanding, the Third Reich-tainted Olympia never found a U.S. distributor, and a dejected Riefenstahl sailed for Germany. It must have been very depressing to know that the sneaky Herr Jäger had betrayed her. And, despite his assurances to the contrary, Jäger was not aboard for the return voyage. Riefenstahl's betrayal was doubly painful, since she had gone out of her way to have Jäger accompany her to America, against the protestations of Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, who had earlier kicked Jäger (whose wife was Jewish) out of the Reich Literature Chamber.

The Denazification Ordeal

Following the war in 1945, Riefenstahl had to face Allied charges that she was a Nazi or a Nazi sympathizer. Her close ties to Hitler and her propaganda films, most notably Triumph of the Will, made her an obvious target. She endured post-war chaos and was imprisoned (and escaped!) three times trying to get to her mother's house in Austria where she was reunited with her husband and arrested again – not once but twice. This time she sat in a real prison as a guest the Seventh American Army, in the company of people like Hermann Göring and Sepp Dietrich (of the SS). But after her interrogation the Americans officially “denazified” Germany's most notorious film director and released her “without prejudice” on June 3, 1945.

A relieved Riefenstahl returned to her film library and editing suite in Kitzbühel in the Austrian Tyrol, where she had moved during the war to avoid Allied bombing in Germany and to continue her work on the long-delayed Tiefland, which she had begun in 1940.But she had not reckoned on the French. The Americans were leaving Tyrol, which was to become part of the new French occupation zone. Despite being advised to move to the American zone, Riefenstahl was reluctant to move her massive film library (including the Olympia negatives) and she believed that her American denazification was valid for all the Allied powers.

That soon proved to be a mistake. Before long Riefenstahl found herself under arrest once again, this time by the French. They decided to move Riefenstahl to the French zone in Germany, where she ended up in the bombed-out ruins of Breisach near Freiburg. Her old “friend” there, Dr. Fanck, refused to have anything to do with her, and she and her husband lived under house arrest in Breisach and later in Königsfeld in the Black Forest. Eventually Riefenstahl was placed in an insane asylum in Freiburg for three months before her release in August 1947. But it was not until July 1949 that she was officially denazified by a French tribunal. Even that “final” decision was appealed by the French military government and the matter was closed six months later when the Baden State Commissariat classified Riefenstahl in absentia as a “fellow traveler.”

But Riefenstahl was far from free. Freedom and partial denazification did not mean she could resume her career as a director, and she had more legal trials ahead of her. The French were still holding all the film material taken from her house in Austria. Even her marriage was falling apart. To top it all, her attempts to get her Tiefland film back from the French were now being hindered by the release of a so-called Eva Braun Diary (a fraudulent precursor of the later and equally bogus Hitler Diary), the work of Luis Trenker, a former co-star with Riefenstahl in several films, now turned director and con-artist. As is usually the case, a court ruling that the Eva Braun diary was a fabrication failed to stop the false rumours and innuendo the diary had produced. In a bizarre twist, Riefenstahl received an unsolicited affadavit of support from none other than her former foe Ernst Jäger.

The Nazi Pin-up Girl

Although she scouted film locations in Africa (where she had a bad car accident and almost died) and had serious plans to make other films (one titled “The Red Devils”), it was not to be. Riefenstahl encountered resistance and protest from too many quarters. There was almost no prospect of getting a Riefenstahl film shot, much less shown in most of the world. So, she did the next best thing; she took up still photography.

She lived for a time with the Nuba tribe in Sudan; recording images that have appeared in two photographic essay books. She took up scuba diving in 1970s at the age of 72, and has continued underwater photo work into her 90s.

To her dying day controversy surrounded Riefenstahl wherever she went and wherever her work was displayed. In March 1946, even before the French threw her into an insane asylum, Budd B. Schulberg wrote an article about Riefenstahl for the Saturday Evening Post. Its title was a taste of things to come: “Nazi Pin-up Girl: Hitler's No. 1 Movie Actress.”

An exhibit of Riefenstahl's movie stills and her African and underwater photographs in Hamburg in late 1997 brought out a whole new generation of protesters. Their signs read: “Now showing: Nazi exhibition” and “No commercializing of fascist aesthetics.” First published in the 1970s, not even her still photographs of naked Nubians have been immune from controversy. Critics somehow managed to see fascist tendencies in Riefenstahl's images of African natives–a race deemed inferior by the Nazis.

The 1993 film documentary about Riefenstahl by Ray Müller, The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl, is available in videotape and DVD versions. It's a fascinating, if somewhat long (188 min.), look at her films and her point of view. The original German title better conveys the thrust of Müller's film: Die Macht der Bilder (“The Power of Images”).

Evidence of Nazi Collaboration

A 2024 documentary titled “Riefenstahl,” directed by German filmmaker Andres Veiel, reveals startling truths about Riefenstahl. Contrary to her lifelong claims of ignorance about the Nazis’ atrocities, the film uncovers evidence that Riefenstahl not only knew about the mass murders but even ordered the “cleansing” of Jews during a 1939 shoot in Poland. Veiel’s access to Riefenstahl’s estate also exposes her deep admiration for Hitler and her ongoing regret over the Nazi regime’s downfall. The documentary challenges Riefenstahl’s post-war portrayal as a victim and sheds light on her continued association with Nazi sympathizers until her death.

Riefenstahl Films - As Actress

Die Bergfilme/The Mountain Films

In the 1920s and '30s, Riefenstahl appeared in a series of so-called Bergfilme directed by Arnold Fanck. The plot of such films was always secondary to the spectacular scenes of the Bavarian and Austrian Alps. The central theme was always human surrender to the power of nature. The Bergfilme played a significant role in shaping Riefenstahl's own approach to filmmaking.

Der heilige Berg (1926, The Sacred Mountain)

Directed by Arnold Fanck. Studio: Ufa. Also known as Peaks of Destiny.

Der große Sprung (1927, The Great Leap)

Directed by Arnold Fanck. Studio: Ufa. Also known as Gita, the Goat Girl.

Die Vetsera/Das Schicksal derer von Habsburg (1928, The Fate of the House of Hapsburg)

Directed by Rolf Raffe. Also known as The Tragedy of Mayerling.

Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü (1929, The White Hell of Piz Palü)

Directed by Arnold Fanck and G.W. Pabst. Studio: Sokal.

Stürme über dem Mont Blanc (1930, Storms Over Mont Blanc)

Directed by Arnold Fanck. Also known as Avalanche. Her first sound film was dubbed in the studio because the sound cameras of the day were too heavy to use in the mountains.

Der weiße Rausch/Sonne über dem Arlberg (1931, The White Frenzy)

Directed by Arnold Fanck. Studio: Sokal. Also known as Avalanche.

Das blaue Licht (1932, The Blue Light)

As Junta, the mountain girl. Riefenstahl also directed. > Buy this movie on Video

SOS Eisberg (1933, SOS Iceberg)

Directed by Arnold Fanck and Tay Garnett. Studio: Universal. Riefenstahl as the pilot Hella, who is trying to find her lost pilot husband in the Arctic ice. A German-American coproduction shot on location in Greenland.

Tiefland (1954, Lowland)

As Martha. Riefenstahl also directed. Release was delayed by the war and Riefenstahl's Nazi connections.

Die Macht der Bilder: Leni Riefenstahl (1993, The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl)

The then-90-year-old Riefenstahl in her own words. An award-winning documentary with many clips from her own films, directed by Ray Müller.

Die Nacht der Regisseure (1995, The Night of the Filmmakers)

Directed by Edgar Reitz. Riefenstahl has an uncredited role as herself in this German production.

Riefenstahl Films - As Director

Das blaue Licht (1932, The Blue Light)

Riefenstahl's directorial debut, in which she also played the role of Junta, the mountain girl. Re-edited and re-cut by Riefenstahl in 1951.

Sieg des Glaubens (1933, Victory of Faith)

A practice run for Riefenstahl's much better Triumph des Willens. Filmed at the Nuremberg rallies of 1933.

Triumph des Willens (1934, Triumph of the Will)

This documentary of Hitler and the Nuremberg rallies is considered a masterpiece of cinematic propaganda.

Tag der Freiheit (1935, Day of Freedom)

A 25-minute short consisting of outtakes from Triumph. Also known as Day of Freedom - Our Armed Forces.

Olympia (1938, Olympia)

Riefenstahl's classic documentary of the 1936 Olympics in Berlin was released in two parts: Fest der Völker (“Festival of Nations”) and Fest der Schönheit (“Festival of Beauty”). It took her almost two years to sort and edit the film. The Olympia crew of 60 cinematographers had shot over 1.3 million feet of film on three different types of film stock. The film premiered on Hitler's birthday, April 20, 1938 - after a month's delay caused by his annexation of Austria.

Tiefland (1954, Lowland)

Riefenstahl also played the role of Martha. Release was delayed by the war and Riefenstahl's Nazi connections.

Impressionen unter Wasser (2002, Underwater Impressions)

Riefenstahl planned to release her first film since Tiefland in 1954 on her 100th birthday.

Sources: The German Hollywood Connection © 1997-2003 Hyde Flippo.

Ze'ev Avrahami, “Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl knew about Hitler's atrocities, film reveals,” Ynet, (August 28, 2024).

“Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s set directions may have led to killing of Polish Jews,” Times of Israel, (August 29, 2024).

Photo by Documentaires.org