Israel Studies An Anthology : Israel's War on Terrorism: Historical and Political Perspective

by Arie Perliger (April 2009)

Introduction

March 2002 was a devastating month for the citizens of Israel. The country was in the midst of the Al-Aqsa intifada and the suicide attack campaigns of the Palestinian organizations had reached their peak. Eleven times during this month, suicide bombers blew themselves up in the streets of Israel’s cities, causing more than 579 casualties including 81 fatalities. [1] On another six occasions that same month, the Israeli security forces thwarted attacks before the suicide bombers were able to complete their missions. The Israeli political leadership, however, was not ready to increase its response to the Palestinian attacks. The Israel Defense Forces were instructed to continue limited raids on the infrastructure of the Palestinian organizations in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, actions which included mainly arrests and intelligence gathering operations. This policy of restraint changed after the night of March 27.

In the evening hours of that day, 250 guests were sitting in the festive Park Hotel dining room, cheerfully celebrating the Passover holiday seder. Around 8:00 pm the celebration was halted. A Hamas operative by the name of Abd al-Basset Muhammad Odeh walked into the room and detonated an explosive device that was attached to his upper body. The aftermath was appalling. Twenty-nine Jews were killed and another 144 were injured. [2]

The particular horrors of the attack and the fact that it was carried out on the Jewish holiday that celebrates the freedom of the People of Israel created a public and political environment that essentially left Israeli policy makers with no option but to respond with force. Thus, only two days later, IDF troops flooded the West Bank and officially began Operation “Defensive Shield.” In less than two weeks, IDF forces regained control of all of the metropolitan areas in the West Bank as well as the refugee camps, which housed the main logistical infrastructure of the Palestinian organizations. [3]

This order of events is not unique in the history of Israel’s response to terrorism. The Israeli counterterrorism policies through the years have systematically included two stages: The initial response is the dispatch of regular infantry, special forces or aerial forces for retaliatory attacks against the terrorist organizations’ infrastructure. In the majority of cases this proved to be futile in terms of operational effectiveness and Israel eventually initiated a massive military operation. The only exception to this rule is the struggle against terrorist organizations that have operated outside the Middle East. In these cases, Israel has opted for direct attacks on the leadership echelon of the organizations. Along with its offensive responses, Israel has also adopted defensive mechanisms to maintain the personal security of its citizens. What are the specific features of Israel’s counterterrorism strategies? Have these features truly remained unchanged or have they evolved over the years? Have they been successful in operational or political terms? The answers can be found in the following historical analysis of Israel’s struggle against terrorism.

Models of Counterterrorism

For almost four decades scholars have been studying how democratic governments cope with terrorism. [4] In the majority of cases they refer to the term “counterterrorism” as a generic concept which describes the overall measures taken by a state to reduce the volume and impact of terrorist attacks against its citizens. Some scholars also tend to distinguish between “combating terrorism,” which encompasses offensive operations against the terrorists and “anti-terrorism”, which covers the broad area of non-offensive means. The latter includes the facilitation of “soft power,” which is political and social reforms that encourage the terrorists to abandon their violent path, while undermining the popular support that they enjoy. [5]

Table 1 – Counterterrorism Models

Model | Reconciliatory | Criminal justice | Expanded Criminal Justice | War |

Goals | Reducing terrorists motivation to use violent means | Punishing and rehabilitation of terrorists and deterring potential future terrorists. | Punishing and rehabilitation of terrorists and deterring potential future terrorists. | Eliminating terrorist operatives/groups. |

Means | Negotiations, Political reforms, Concessions. | Penalization of terrorists while adhering to the ‘rule of law’ | Penalization of terrorists while enhancing the authority of the criminal justice system and limiting the rights of suspects in terrorist’s activity. | Total destruction of the terrorist’s infrastructure. |

Agents | Policy makers, brokers and diplomats | Police and the criminal justice system | Police, clandestine services and the criminal justice system | Clandestine services and military units. |

Four counter-terrorism models (see Table 1) have been developed to explain the factors that influence state response to terrorism. On one end of the spectrum are the non-violent defensive and reconciliatory models and, on the other, the violent criminal justice and war models. The reconciliatory model refers to conflict that has been resolved by negotiations between the regime and the terrorist group or through unilateral political reforms by the former that are intended to reduce the group’s motivation to continue to use violence. [6] The criminal justice model was practiced mainly by European democratic states between the 1960s and the 1980s. These countries were preoccupied with conflicting demands. On the one hand, they wanted to ensure the safety of their citizens and, on the other, they were committed to adhering to liberal democratic principles in their response to the threat. Thus, the states “criminalized” the phenomenon of terrorism and responded to it through the criminal justice system. [7]

The expanded criminal justice model was the democratic states’ response in the 1980s and 1990s to the ineffectiveness of the pure criminal model. They needed to find a reasonable balance between democratic acceptability and effectiveness in the struggle against terrorism. The expanded model adds special counterterrorism legislation that does not necessarily meet liberal, civil rights values with the standard tools of the criminal justice system. Such legislation includes laws that limit the rights of suspects involved in terrorist activity, expand the authority of the law enforcement and security agencies and introduce new legal mechanisms to limit the free operation of organizations promoting non-consensual radical ideologies.

Administrative detentions and the establishment of special courts for terrorist offenses are also elements that are often used as part of the expanded criminal justice model. [8] The model that has gained more ground in the last decade is the war model. Terrorism, from the perspective of this model, is considered an act of extreme aggression or war that poses a strategic threat to a state and is therefore seen as a serious challenge that must be countered with the power of the state’s military apparatus and intelligence services. [9] It is worth noting that the various counterterrorism models are not mutually exclusive and that policy makers tend to apply one or more of them at the same time. The difference lies in the relative weight of each model in an overall counterterrorism policy at any given time.

Terrorism and the State of Israel

The Israeli experience with terrorism can be divided into three major types: The first type includes terrorism originating from over Israel’s borders and perpetrated by Palestinian or Islamic groups that have created a military infrastructure in neighboring countries. The second type is international terrorism against Israeli targets outside Israel’s borders including aviation terrorism initiated by Palestinian groups from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, as well as attacks against Israeli diplomatic facilities and representatives during roughly the same period. Except for the 1992 and 1994 Hezbollah attacks in Argentina against the AMIA building and the Israeli embassy and several more attacks in the last few years, international terrorism against Israeli targets virtually disappeared in the mid 1980s. The third type includes attacks perpetrated within the State of Israel by groups whose organizational infrastructure is located inside Israel or in areas under Israeli control. These include the cases of Palestinian violence during the first and second Intifadas and the various attacks that occurred between these two clashes; namely the campaigns of suicide attacks initiated by Hamas and the PIJ (Palestinian Islamic Jihad) in the 1990s. In the following sections these three types of terrorism and the subsequent Israeli responses will be described in detail.

Israel's Struggle with Border Terrorism

The Israeli struggle with border terrorism can be divided into three main periods: The mid- 1950s, the late 1960s and the mid-1970s to the late 1990s. In most cases Israel responded by using different variations of the war model. Operational factors can explain this response. In democracies, the military apparatus is the main actor responsible for protecting the state borders, as well as responding to attacks initiated outside the country. In the mid-1950s, cells of Palestinian combatants (Fedayeen) infiltrated Israel from the Jordanian and Egyptian borders. They were recruited from the Palestinian population in the refugee camps and trained and dispatched by the intelligence services of the two countries. The Fedayeen attacked isolated Israeli settlements and ambushed Israeli vehicles on the roads.

Figure 1 – Fedayeen Attacks 1952-1956 [10]

* Source: NSSC Dataset on Counterterrorism, See: http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/; Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press.

As a result of the intensification of the Fedayeen attacks (see Figure 1), the Israeli leadership was forced to find ways to cope with the challenge and in July of 1953, the IDF formed its first counterterrorism force—Unit 101[11] The Israeli military leadership decided that retaliatory attacks would be able to deter the Palestinian recruits and damage the Fedayeen’s military infrastructure. The military presented the political leadership with the positive potential of dispatching small commando units to perform raids against concentrations of civilians and military personnel in the areas where infiltrators originated. The unit operatives would have to quickly cross the border into Jordan or Egypt, strike the targets and disappea[12] It should be noted, however, that the IDF Chief of Staff, Mordechai Maklef, approved the establishment of such a unit much to the disappointment of the Head of IDF Operations Division, Moshe Dayan. Dayan objected to the concept of activating IDF units for retaliatory attacks[13] Regardless, on August 5, 1953, the directive to establish the unit was issued and the young Ariel Sharon was appointed as its leader.

Despite the fact that Unit 101 was admired by many in the Israeli public, the unit was incorporated into the Paratroopers Brigade only a short while after its establishment.[14 This was due mainly to the criticism directed at Prime Minister David Ben Gurion in the wake of the operation at the Qibya village in Samaria on October 14, 1953, which was a response to the killing of a Jewish mother and her two children in the town of Yahud. The Israeli public had demanded a fitting act of retribution; however, during the operation, which included the destruction of a residential building in the village, the 101 unit failed to confirm evacuation of the buildings. Consequently, sixty-nine Palestinians were killed. World public opinion responded with severe denunciation and ten days after the operation, Israel received an official condemnation by the United Nations Security Council [15] Shortly thereafter, the first commando unit of the IDF was disbanded. [16] From an operational perspective, the unit had also not succeeded in reducing the level of Fedayeen terrorism (see Figure 1) and, after it was dismantled, Palestinian violence continued in full force. In 1956, Israel concluded that only a massive military operation would be effective in countering the Palestinian violence and indeed, the 1956 war (the “Kadesh Operation”) was what eventually led to the elimination of the Egyptian Fedayeen brigade. Thus, while the 1956 war was driven by broader factors in the region, it provided a terminal solution to the Egyptian Fedayeen problem.

Israel’s decisive military victory in the 1956 war had other consequences in addition to the elimination of the Fedayeen. Among these was the increasing understanding among a growing number of Palestinians that more severe methods should be utilized in order to promote their political aspirations. Hence, in 1957, Fatah—the National Movement for the Liberation of Palestine— was established. The leaders of Fatah were inspired by the struggle of Third World countries against colonialism and especially that of the FLN (National liberation front) struggle against the French in Algeria, as well by revolutionary texts such as Franz Fanon’s, The Wretched of the Earth.[17] Fatah contended that only a political and violent struggle against Israel led by the Palestinian people could potentially advance the creation of an independent Palestinian political entity.[18]

Fatah did not remain the leading force in the Palestinian conflict for long. Shortly after its establishment, other competing organizations emerged. In January 1964, under Egyptian patronage, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) was created with Ahmad Shukeiri at its head. Like the Fatah, the PLO created an armed division (the Palestinian Liberation Army, PLA) to operate in parallel to its political apparatus. Tension between Fatah and the PLO began to appear immediately thereafter. It subsided only five years later when Yasser Arafat and his Fatah supporters took control of the PLO and transformed it into an umbrella organization for the majority of Palestinian groups. [19]

Other prominent Palestinian terrorist groups appeared in the late 1960s. Some of them combined left-wing ideology with Palestinian nationalism (such as the Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine) while others were proxies of Arab countries aspiring to be involved in the Palestinian violent struggle (e.g., the Arab Liberation Front was affiliated with the Iraqi regime is a case in point.) In the mid 1960s, Fatah, looking for a viable front for its armed struggle, established a military infrastructure in Jordan and from there it dispatched terrorist cells to initiate attacks against Israeli civilian and military targets. Fatah’s first terrorist attack was carried out in January 1965, when several operatives crossed the Israel-Jordan border and tried to sabotage Israeli water facilities. [20]

Gradually the organization’s operations became much bolder and more effective. The most severe attack occurred on October 7, 1966. On that night Fatah members hid explosives at the entrances to several buildings on Gadera Steet in the Romema neighborhood of Jerusalem. Seven residents were injured as a result of the blasts and severe damage was caused to many apartments. [21]

The increase in Palestinian terrorism after the Six-Day War was a result of both operative and political factors. Paradoxically, the Israeli military successes during the Six-Day War made Israel more vulnerable to the terrorist campaigns of the Palestinian groups. Israel was now compelled to deal with a new population of more than two million Palestinians who lived in the West Bank. Additionally, Israel gained a new border with the Jordanian Kingdom that entailed more than 350 miles of unfenced and unprotected frontier land, with only the Jordan River as a natural barrier. Fatah took full advantage of these conditions. Fatah cells crossed the border on an almost daily basis to engage in ambushes, attacks on isolated Israeli settlements and explosive planting in civilian facilities in Israeli cities, mainly in Jerusalem. [22]

Between the years 1968 and 1970, Fatah initiated more than 140 attacks. Fatah also tried to establish a terrorist infrastructure in the West Bank with Yasser Arafat secretly roaming the West Bank shortly after the war. This attempt was largely unsuccessful, however, mainly because of the ability of the GSS [General Security Service] to lay out an efficient human intelligence network in Palestinian towns and villages as well as the firm control of the military administration over the local Palestinian population. [23]

From a political perspective, in the wake of the defeat of the Arab states in the 1967 War, the Fatah leadership assumed that every triumph after the war would be considered an accomplishment and would help to reinforce Fatah’s standing in the Arab world. Indeed, the Battle of Karameh, in which several hundred of the organization’s members thwarted the Israeli attempt to take over the Karameh military outpost near the Israeli-Jordanian border and inflicted significant casualties on the Israeli raiding force, earned the organization much prestige among the Arab nations and consequently swelled its ranks with new recruits. [24] The Israeli response took on offensive as well as defensive dimensions. The offensive measures included systematic retaliatory attacks of IDF elite infantry against Palestinian compounds in Jordan. Israel’s defensive measures consisted of establishing extensive IDF patrols along the Jordanian border. [25] The defensive efforts also included the establishment of Unit 299 whose role it was to track down cells that had succeeded in crossing the border and with the assistance of other forces, to eliminate them. [26] Unlike the 1950s, this time Israel did not need to initiate a full-scale military operation to solve the problem of Palestinian terrorism. Jordan expelled all Palestinian groups from the country in September 1970, in what was called “Black September.” More than 10,000 members of the Palestinian terrorist groups were killed by the Jordanian legion that month and thousands of others escaped through Syria and settled in Lebanon.

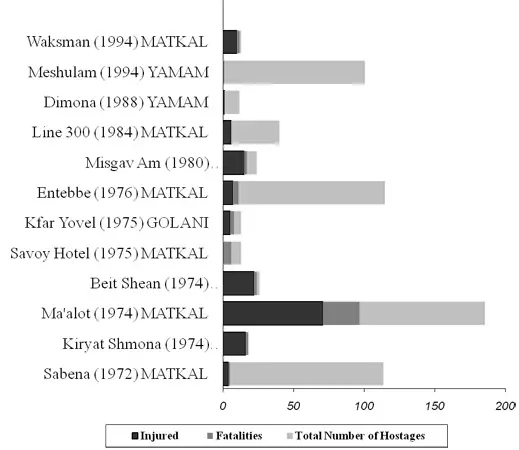

The Palestinian groups reestablished their military and organizational infrastructure relatively quickly, using southern Lebanon as a base for training and dispatching terrorist cells to attack targets inside Israel. Many of these attacks included kidnappings, such as the Ma’alot incident in which, on May 15, 1974, a terrorist cell attacked a school in the small northern town of Ma'alot and captured over one hundred hostages, mostly schoolchildren. The attempted rescue operation by the IDF elite Special Forces Unit, the Sayeret Matkal (General Staff Reconnaissance Unit) failed and the incident ended with the deaths of twenty-two children and three adults. Other attacks were characterized by similar features (see Figure 2). [27]

Figure 2 - Hostage Rescue Missions, 1972-1994

* Source: NSSC Dataset on Counterterrorism, See: http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/; Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Along with raids on Palestinian bases in northern Lebanon, the Israeli response included an intensification of the specialization of the IDF elite military units in reacting and thwarting hostage incidents. Almost simultaneously, the YAMAM (Police Counterterrorism Unit) was founded in 1974. This was the result of recommendations made by the Horev Committee, which investigated the Ma'alot disaster. The committee’s rationale was that in contrast to the elite units of the IDF, which specialize mainly in intelligence gathering beyond enemy lines and for whom anti-terrorist activities are of secondary importance, this special police unit would be trained first and foremost to act in scenarios directly linked to terrorism. [28]

Nonetheless, in most cases, even after the YAMAM became active, the Israeli leaders continued to prefer the use of military units in such incidents. Political and sociological reasons explain this; among them the high proportion of the Israeli political leadership who had emerged from the military, as well as the strong status of the IDF among the Israeli public. Nevertheless, Israeli experience clearly shows the advantage of using the police Special Forces over the military (see Figure 2).

On March 11, 1978, a Palestinian terrorist cell took over an Israeli bus on the coastal road. During the unsuccessful rescue operation, 35 passengers were killed and 71 were injured. Prime Minister Menachem Begin declared in the Knesset: “Gone forever are the days when Jewish blood could be shed with impunity!” [29] Three days after the “Blood Bus” attack, Israeli forces launched the Litani Operation during which they pushed Palestinian forces beyond the Litani River in Lebanon. This did not put an end to the attacks on northern Israel. Fatah attuned itself to the new operational conditions by launching Katyusha rockets toward Israel’s northern settlements. [30] Intensive retaliation by the Israeli Air Force led to the signing of ceasefire agreements between the two sides in June 1981. The following year, the understandings gradually eroded, eventually leading to the first Lebanon War in June 1982. Israeli forces eliminated the infrastructure of the Palestinian terrorist organization in the country, forcing its leaders to flee to Tunisia.

The aforementioned ritual of raids followed by full-scale war became a patented move in Israel’s struggle against terrorism from its northern border. This was also evident during operations “Accountability” and “Grapes of Wrath” against Hezbollah. In both cases, escalation of the violence and an unusually bloody attack with an unprecedented psychological effect eventually led the Israeli government to step up its military response.

Between 1982 and 1990 Hezbollah evolved into one of Israel’s most sophisticated and successful adversaries. From a small insurgency group of southern Lebanese Shiites who were trained by the Iranian revolutionary guard, it became one of the most prominent political and military actors in the country. Shortly after its establishment, Hezbollah initiated a campaign of suicide attacks against Israel and its affiliated militia in southern Lebanon: The SLA (Southern Lebanon Army).

After three years and more than 20 suicide attacks, Hezbollah claimed victory as Israel decided to withdraw from Lebanon and to deploy its forces in a “security strip”— a 3-5 mile buffer zone north of the Israeli-Lebanese border. [31] The two sides continued to clash on southern Lebanese terrain. Hezbollah demanded the complete withdrawal of Israel from Lebanon and it initiated attacks against Israeli posts, ambushed Israeli convoys and planted remote control bombs near Israeli or SLA facilities. Israel responded with limited air and ground raids. After years of confrontation, however, Hezbollah succeeded in killing six Israeli soldiers in less than two weeks in mid-July 1993 and continued to target the northern Israeli settlements with Katyusha missiles. In the face of public discontent, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin visited the Israeli northern settlements and assured their inhabitants that Israel would retaliate. Indeed, a few days later, on July 25, Israel launched “Operation Accountability” and heavily bombarded villages and towns in southern Lebanon.

The Israeli leadership hoped that the Israeli bombardment would cause masses of Lebanese refugees to flee north toward Beirut. This, in turn, would put pressure on the Lebanese government to force Hezbollah to put down its arms. [32] The plan did not have any profound effect on Hezbollah’s operational capabilities and the terrorist group continued to fire Katyusha missiles at northern Israel. [33] On July 31, the operation came to an end after Israel and Hezbollah came to a ceasefire agreement. At the core of this agreement was the understanding that neither side would attack civilian populations.

The guerrilla warfare between the two sides continued, however, and in 1995 Israel formed a new specialized counter-guerilla unit called “Egoz”. The unit’s soldiers were principally instructed in camouflage, ambushes and micro-warfare. [34] Shortly after the establishment of “Egoz” however, Hezbollah intensified its Katyusha attacks on northern Israel, thus openly violating the “Accountability” understandings. [35] These attacks continued despite attempts by the international community to prevent an escalation of violence. The heaviest bombardment occurred on April 9, 1996. [36]

Two days later, the Israeli Air Force and IDF Artillery Corps began to engage in heavy shelling of Hezbollah compounds in southern Lebanon while the Israeli Navy imposed a blockade on the ports of Tyre and Sidon. The circumstances of three years earlier emerged again. While thousands of Lebanese refugees fled from southern Lebanon, Hezbollah continued to strike northern Israel with Katyusha missiles. [37] Again it was clear that Israel’s military operation, “Grapes of Wrath,” had little effect on Hezbollah operational capabilities. The operation ended as a result of mounting pressure from the international community, which followed the accidental bombing of a UN refugee compound near the village of Qana on April 18 that killed 102 civilians and injured more than 100. [38]

A ceasefire agreement was subsequently signed by Israel, Syria and Lebanon on April 27, ending the “Grapes of Wrath.” [39] Israel’s long-term struggle against border terrorism did not end even after IDF forces evacuated the “Security Strip” on May 24, 2000. Hezbollah attacks continued and ultimately prompted another Israeli operation in the summer of 2006.

Similarly, the evacuation of all IDF forces and Israeli settlers from the Gaza Strip as part of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s “Disengagement Plan” in 2005 did not end the terror threat posed by Hamas. Though Israel managed to prevent terror infiltrations, Hamas altered its tactics and began to make greater use of rocket and mortar attacks to threaten the civilian population of southern Israel. Despite a series of military operations, including the large-scale “Cast Lead” invasion in December 2008-January 2009, Israel has not yet found an effective response to this new challenge. Before elaborating upon the historical and political conditions that allowed Hamas to become the strongest political and military actor in the Palestinian arena, an analysis of Israel’s struggle with international terrorism must be presented.

Israel's War Against Terrorism in the International Arena

On April 23, 1968, three members of the PFLP (Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine) hijacked an El Al Boeing 707 that was on its way from Rome to Tel Aviv. They landed the plane in Algiers and, after four days of negotiations, the 48 hostages were eventually freed. In exchange, Israel released 16 Palestinian prisoners. [40] This event was the first in a string of 126 attacks against Israeli targets outside the country’s borders. The majority of international attacks occurred between the late 1960s and the early 1980s and included mainly aviation terrorism, attacks against Israeli diplomatic facilities and international representatives of Israeli governmental firms. Most of the attacks were perpetrated on European soil by Palestinians who had been trained by various terrorist organizations in the Middle East.

Israel instituted new defensive measures to address these threats. Strict security procedures were put into place on all El Al flights and at airports that dispatched any flights to Israel. [41] One tactic that proved quite effective was to assign armed sky marshals to all El Al flights. The marshals were trained by the GSS and disguised as regular passengers. In February 1969, five PFLP members were overpowered by Mordechai Rechamim, a sky marshal, while they tried to take control of an El Al flight that was en route from Zurich to Tel Aviv. [42] A similar scenario occurred a year and a half later, in September 1970, when El Al security personnel thwarted an attempt by two PFLP terrorists to take control of a flight from Amsterdam to New York. [43]

Also going on the offensive, Israeli leadership developed the concept of “no surrender” in the face of the demands of terrorists during hostage incidents. [44] Instead, IDF elite units advanced their training for hostage rescue missions. The well-known rescue operation of the Israeli hostages in Entebbe, Uganda, in July 1976 is a case in point.

Moreover, in the absence of a viable military response against Palestinian cells operating in other sovereign countries, most of them being Western democracies, Israel’s political leadership adopted the tactic of striking at Palestinian terrorist leaders residing abroad. Most of these targeted assassinations were conducted within the framework of “Operation Wrath of God,” which was triggered by the murder of the eleven Israeli athletes during the 1972 Munich Olympic Games by Black September operatives.

Table 2 - 'Wrath of God' Assassinations

Function | Affiliation | Place | Date | Name |

Senior operative in Europe | Fatah/Black September | Rome | 10/16/1972 |

|

Fatah representative in France. | Fatah/Black September | Paris | 12/8/1972 |

|

Fatah representative in Cyprus and liaison to the KGB | Fatah | Nicosia | 1/25/1973 |

|

Official PFLP representative in France. | PFLP | Paris | 4/6/1973 |

|

No. 2 in the PLO hierarchy, head of the organization’s Political Department | Fatah | Beirut | 4/10/1973 |

|

PLO spokesmen | Fatah | Beirut | 4/10/1973 |

|

In charge of terrorist activity in the West Bank | Fatah | Beirut | 4/10/1973 |

|

Official Fatah representative in Cyprus | Fatah | Nicosia | 4/10/1973 |

|

Black September operative. | Black September | Athens | 4/11/1973 |

|

Black September operative. | Black September | Rome | 6/13/1973 |

|

Liaison officer between Black September and Fatah in Europe. | Black September | Paris | 6/28/1973 |

|

Head of Black September | Black September/Fatah | Beirut | 1/22/1979 |

|

Sources: Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press; Aharon J. Klein, Striking Back (Tel Aviv: Miskal, 2006). (Hebrew); Stewart Steven, The Spymasters of Israel (New York: Macmillan, 1980); Ephraim Kahana, Historical Dictionary of Israeli Intelligence (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006); Michael Bar-Zohar and Eitan Haber, The Quest for the Red Prince (London: Widenfeld and Nicolson, 1983).

In its initial stages, the operation was aimed at the top leaders of the Black September organization; but Israel gradually expanded its of targets to include operatives of other groups such as the PFLP (See table 2). Only some of the targeted Palestinians were political figures, spokespeople or other operatives in the bureaucracy of the organizations with limited operational roles but with visible public profiles.

While the targeted assassinations did lead to a decline in the intensity of international Palestinian terrorism, it was only a temporary solution (see figure 3). Moreover, most assassinations generated counter assassinations of Mossad operatives and retaliatory attacks. [45] Therefore, an empirical examination would reject the idea that the operation had any long-term influence on the operational capabilities or motivation of Palestinian organizations.

Figure 3 – Palestinian Terrorism (International) 1967-1990

Sources: NSSC Dataset on Palestinian Terrorism, See: http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/; Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press;

The question may be raised as to whether the Israeli leadership really expected that the assassinations would have any meaningful effect on Palestinian terror groups or whether it was perhaps more interested in the public visibility of its response. Rather than preventing terrorism, the operation fulfilled the need to appease an enraged nation after the Munich assault and other similar attacks.

Israel's War on Terrorism - The Internal Realm

The first 30 years of Israel’s existence included limited manifestations of political violence by internal actors; both Jewish militants and radical elements among the Israeli Arab citizens. The first Intifada, which broke out on December 9, 1987, [46] was the first situation in which Israel was forced to confront any significant internal terrorism. The large demonstrations and civil riots that initially made up the whole of the Intifada turned into a systematic Palestinian terrorism campaign in late 1989 which included stabbings, kidnapping Israeli soldiers and shooting attacks against IDF forces and settlers in the West Bank. [47] These attacks were predominantly carried out by two new groups that had emerged in the territories: Hamas and the PIJ. Both organizations combined radical Islamism with nationalist Palestinian sentiments and opposed any conciliatory process with Israel.

The Israeli response to the Intifada was comprised of two types of offensive measures: The first was an extensive use of punishments and deterrence that was intended to reduce the mobilization of West Bank Palestinians for violent activities. These deterrent tactics included the demolition of the houses of terrorists’ families as well as administrative detentions of those suspected of involvement in terrorist activity. Around 430 houses were demolished during the first Intifada (1987-1993) and more than 12,000 administrative prisoners were held in detention camps. [48]

In addition to these methods of deterrence, Israel also engaged in direct strikes against the organizational infrastructure of Palestinian terrorist groups. In order to effectively implement these strikes, the IDF created special units that trained in the fields of micro-warfare and then assimilated them into the local Palestinian population. [49] Thus, the units’ soldiers learned local Arabic dialects and operated under disguise in the territories. These units, called “Samson” and “Duvdevan,” specialized in capturing terrorist operatives and arresting their supporters among the general population.

While the Israeli response to the first Intifada could be viewed as an extreme version of the expanded criminal justice model, shortly after the Israeli Labor Party won the 1992 Israeli elections, Israel resorted to a “conciliatory” approach. The Oslo agreements between Israel and the PLO formally ended the Intifada (which had largely petered out as a result of the 1991 Gulf War) and gradually granted control over the Palestinian urban centers in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to the newly formed NPA (National Palestinian Authority).

Hamas and the PIJ, however, were determined to sabotage the conciliatory process and adopted a new tactic that was to become the symbol of the Palestinian terrorism for almost a decade; namely, suicide bombings. Israel responded with limited raids against the infrastructure of Hamas and PIJ, and demanded that the PNA prevent any continuation of Palestinian violence. For a brief period between 1997 and 1999, the combined pressure by both PNA and Fatah-controlled forces and the IDF and GSS reduced the level of violence. In 1999, there were no suicide attacks and only slightly more than 10 terrorist attacks.

The second intifada, a much more intensive campaign initiated by the Palestinians in October 2000, reintroduced the tactic of suicide attacks. More than 140 such operations were perpetrated by the different terrorist groups, by Hamas and the PIJ until 2002, and then also by secular groups such as Fatah and its affiliates. [50] Because the territories were already partially under the control of the PNA, Israelis returned to the same dynamic that had characterized their response to external terrorism. Specifically, there was a relatively long period during which raids against the Palestinian infrastructure in the West Bank were carried out and, later, after these proved ineffective, a major military operation termed “Defensive Shield” was launched.

In addition to numerous strikes on targets in the territories, the IDF targeted and killed operatives and leaders of the Palestinian groups. Between November 2000 and October 2004, Israeli forces assassinated more than 180 Palestinian operatives. [51] Israel also reintroduced punitive measures such as house demolitions and continued to use administrative detentions. More than 2,600 Palestinians were put under administrative detentions and 664 houses were demolished during this period.

Operationally speaking, the Israeli offensive response led to a decline in the number of suicide attacks, although not of Palestinian terrorism, forcing both PIJ and Hamas to shift their efforts to initiating rocket and mortar attacks instead of suicide bombings. As to whether “Operation Defensive Shield” and the ongoing targeted assassinations were instrumental in the internal political power of the fundamentalist Palestinian groups - as reflected in Hamas’s victory in the 2006 elections conducted in the PNA - there are conflicting opinions. While some argue that the strengthening of Hamas was mainly a result of growing corruption among Fatah leadership, others have found an association between the resulting escalation of the violence and the growing popularity of the fundamentalist organizations as fewer and fewer Palestinians were willing to adhere to the peace process.

By 2006, Israel gradually became more and more reluctant to continue with its policy of targeted assassinations as internal and international voices, among them the Bush administration, asserted that this was a policy of retaliation rather than a preventive measure. This had already been noted by the fact that, while in the first months of the Second Intifada, most Israeli targeted assassinations were actually preemptive attacks against operatives who were considered “ticking bombs,” the assassinations rapidly turned against operatives at different levels of the organizational hierarchies; including political or spiritual leaders. “Ticking bombs” never made up more than 30% of the targeted operatives and in most years, much less. [52]

Concluding Remarks

In contrast to other democracies, Israel’s war on terrorism historically consisted of more than one front. In some cases, the terrorist campaigns were just another facet of Israel’s conflict with her neighbors, who did not hesitate to sponsor and support the Palestinian and Muslim terrorist groups to promote their own interests. Israel’s war on terrorism included continuous efforts to balance between the willingness to preserve the state’s adherence to democratic principles on the one hand, and the need to continue to improve the effectiveness of the anti-terrorism measures and Israeli security on the other.

The Israeli experience provides several insights regarding the dynamics and effectiveness of the various counterterrorism models. While the war model provided some relief in the short term, in most cases it did not yield the desired long-term results and did not prevent the adaptation of the terrorist groups to the changing reality. Both Hezbollah and the Palestinian fundamentalist groups were able to survive Israel military operations and to introduce alternative tactics, enabling them to continue their violent campaigns.

The Israeli experience with terrorism also exemplifies the futility of the conciliatory approach under two conditions: The first condition is when the state adversary is not a unified actor. In this case, even an intensive conciliatory process will not yield effective results and will lead to the collapse of the process. The second situation, in which the conciliatory process becomes irrelevant, is when the adversaries essentially espouse a revolutionary ideology. Hence the emergence of fundamentalist Palestinian movements advocating a vision which promotes the establishment of a Muslim political entity all over the Middle East, including Palestine, limits the ability to attain an effective conciliatory process. While Israel was eventually able to divert Fatah and segments of the PLO from the path of violence, at least temporarily, it was unable to prevent the emergence and growth of more radical adversaries, both on the northern front and on the internal and southern front.

The Israeli experience also provides us with some direction regarding effective responses to terrorism. Terrorism is a psychological warfare in which a few are targeted in order to terrorize the many in the hope that they will influence the political system to respond to the demands of the terrorists. Moreover, terrorism is rarely a strategic threat that jeopardizes the continued existence of a stable polity. Hence, a viable response does not obligate eliminating the terrorist organizations infrastructure but limits their ability to terrorize the masses and gain access to the political system.

A combination of defensive mechanisms which increases the ability of the regime to cope with the phenomena and limits its psychological effects on the public (the elimination of aviation terrorism in the 1970s is a case in point) with timely and well calculated offensive measures which limit the harm to uninvolved civilians and thus reducing the mobilization potential of the terrorist organizations, has a potential to create an hostile environment for terrorist organizations, reducing both their operational capabilities and their motivations. Regardless, it is clear that for Israel the struggle against terrorism is far from over.

Bibliography/Sources:

[1] NSSC Dataset on Palestinian Terrorism, See :http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.

[2] Brinkley, Joel. “Mideast turmoil: Mideast; bomb kills at least 19 in Israel as Arabs meet over peace plan,” 3.28.2002, NY Times.

[3] “Operation Defensive Shield: Special Update, March 29, 2002 - April 21, 2002,” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs Websites, http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/2000_2009/2002/3/Operation%20Defensive%20Shield

[4] Wardlaw, 1989; Wilkinson, 1986) Bremer, Paul. 1992. “The West's Counter-Terrorists Strategy,” Terrorism and Political Violence 4(4), 255-262; Bonner, David. 1992. “United Kingdom: The United Kingdom Response to Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 4(4), 171-205; Cerlinsten, Rolland & Schmid, Alex. 1992. “Western Response to Terrorism: A Twenty Five Year Balance Sheet,” Terrorism and Political Violence 4(4), 307-340; Rienares, Fernando. and Jiame-Jimenez. 2000. “Countering Terrorism in a New Democracy: The Case of Spain,” in Rienares Fernando. (Ed.) European Democracies against Terrorism. Dartmouth: Ashgate; Wardlaw, Grant. 1989. Political Terrorism: Theory, Tactics and Counter-measures Sec. Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Wilkinson, Paul. 1986. Terrorism and the Liberal State. Hong Kong: Macmillan.

[5] Hoffman & Morrison-Taw. 2000. “A Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism” in Rienares Fernando (ed.) European Democracies against Terrorism. Dartmouth: Ashgate, 12-28.

[6] Sederberg, C.P.1989. Terrorist Myths: Illusion, Rhetoric, and Reality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Schmid, Alex P. 1988. “Force or Conciliation? An Overview of Some Problems Associated with Current Anti Terrorist Response Strategies,” Violence, Aggression and Terrorism 2(2): 149-178.

[7] Cerlinsten, Ronald .D. & Schmid, Alex. 1992. “Western Response to Terrorism: A Twenty Five Year Balance Sheet,” Terrorism and Political Violence 4(4), 307-340.

[8] Pedahzur, Ami and Ranstorp, Magnus. 2001. “A Tertiary Model Countering Terrorism in Liberal Democracies: The Case of Israel,” Terrorism and Political Violence 13(2), 1-26.

[9] Cerlinsten, Ronald. 1987. “Power and Meaning,” in Wilkinson P. & Stewart A.M. (eds.) Contemporary Research on Terrorism. Aberdeen: Univ. of Aberdeen Press, 419-450; Simon, Jeffery D. 1987. Misperceiving the Terrorist Threat. Rand Publication Series, R-3423-RC, June; Clutterbuck, Lindsay. 2004. “Law Enforcement” In Ludes, M. James and Cronin, Audrey, K. Attacking Terrorism, Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press, 140-161; Hocking, Jenny. 2003. “Counter-Terrorism and the Criminalization of Politics: Australia's New Security Powers of Detention, Proscription and Control", Australian Journal of Politics and History, 49(3): 355-371.

[10] Black, Ian and Morris, Benny. 1992. Israel’s Secret Wars. London: Warner, 120-121; Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 1.

[11] Tevet, Shabtai “Old Versions, New Versions,” Haaretz, September 16, 1994, B5. (Hebrew).

[12] Benziman, Uzi. 1985. Sharon: An Israeli Caesar. New York: Adama Books, 42-44.

[13] Tevet, Shabtai “Old Versions, New Versions,” Haaretz, September 16, 1994, B5. (Hebrew); Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 1.

[14] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 1.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Laqueur, Walter. 2001. A History of Terrorism. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 205-206.

[18] Abou Iyad. 1978. With No Homeland. Talks with Eric Rouleau. Tel-Aviv: Mifras (Hebrew).

[19] Tessler, Mark. 1994. The History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Indianapolis: Bloomington & Indiana University Press, 376-377, 660.

[20] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 2.

[21] “Suddenly I felt I was flying in the Air,” Maariv, October 9, 1966, 1 (Hebrew).

[22] NSSC Dataset on Palestinian Terrorism, See: http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.

[23] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 2.

[24] Terrill W. Andrew. 2001. “The Political Mythology of the Battle of Karameh,” The Middle East Journal 55(1), pp. 99-111.

[25] Hani Ziv and Yoav Gelber, Sons of the Bow:A Hundred Years of Struggle, Fifty Years of IDF (Ministry of Defense, 1998), 278. (Hebrew).

[26] Ziv and Gelber, Sons of the Bow :A Hundred Years of Struggle, Fifty Years of IDF, 278; Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 2.

[27] “Twenty Killed and Seventy Wounded in Ma'alot,” Haaretz, May 16, 1974, 1 (Hebrew).

[28] “Report of the Investigation Commission on Ma'alot Events,” Yedioth Ahronoth, July 11, 1974, 10 (Hebrew).

[29] Taken from Meron Medzini (ed.), Israel’s Foreign Relations: Selected Documents (Jerusalem: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1977-1979), 359-362. Available at: http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Foreign%20Relations/Israels%20Foreign%20Relations%20since%201947/1977-1979/134%20Statement%20to%20the%20Knesset%20by%20Prime%20Minister%20Beg.

[30] Major George C. Solley “The Israeli Experience in Lebanon, 1982-1985” Global Security site: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1987/SGC.htm.

[31] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 3.

[32] Michael Brecher and Jonathan Wilkenfeld, A Study of Crisis (Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 299-300.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Moshe Tamir, The War Without a Name (Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense Publishers, 2006), 148 (Hebrew).

[35] “Operation Grapes of Wrath – Selected Analyses From The Hebrew Press”, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.israel.org/MFA/Archive/Articles/1996/OPERATION%20GRAPES%20OF%20WRATH%20-%20SELECTED%20ANALYSES%20FROM (issued April 21, 1996)

[36] Ibid.

[37] Kevin Fedarko, “Operation Grapes of Wrath”, Time, April 22, 1996.

[38] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 6.

[39] “Cease-fire Understanding in Lebanon- and Remarks by Prime Minister Peres and Secretary of State Christopher”, Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

http://www.israel-mfa.gov.il/MFA/Foreign%20Relations/Israels%20Foreign%20Relations%20since%201947/1995-1996/Cease-fire%20understanding%20in%20Lebanon-%20and%20remarks%20b (issued April 26, 1996)

[40] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 2.

[41] Moshe Betser and Robert Rosenberg. 1996. Secret Soldier: The True Life Story of Israel’s Greatest Commando. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 84.

[42] “Terror in Two Cities”, Time, (issued February 28, 1969)

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,900684,00.html

[43] “Flight Crews and Security.” Public Broadcasting System, Hijacked website:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/hijacked/peopleevents/p_crews.html (accessed February 17, 2008)

[44] Moshe Zonder. 2000. The Elite Unit of Israel. Jerusalem: Keter, 109. (Hebrew).

[45] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 2.

[46] See: “What Started ‘The First Intifada’ in 1987?” Palestine Facts, http://www.palestinefacts.org/pf_1967to1991_intifada_1987.php.

[47] NSSC Dataset on Palestinian Terrorism, See:http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.

[48] Shalev, Aryeh. 1990. The Intifada: Causes and Effects. Tel Aviv: Jaffe Center for Strategic Studies, 127-129.

[49] Pedahzur, Ami. 2008. The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, chapter 5.

[50] NSSC Dataset on Palestinian Terrorism, See:http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.

[51] NSSC Dataset on CounterTerrorism, See:http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.

[52] NSSC Dataset on CounterTerrorism, See: http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/.