The Starry Sky & the Still Small Voice: The World Within

Medieval Jewish men of science had a mechanistic view of the world and of man; they saw both as marvelous, divinely contrived machines. Not so the teachers of Jewish mysticism, the Kabbalah. Kabbalah had its own cosmogony, with creation as emanation from the One; and its own theosophy, the special relationship between an immanent Creator and the world, and most especially, man. "What exists in God," Gershom Scholem wrote in his Kabbalah (New York, 1987), "unfolds and develops in man."

Man is the perfecting agent in the structure of the cosmos ... the process of creation involves the departure of all from the One and its return to the One, and the crucial turning-point of this cycle takes place within man, at the moment he begins to develop an awareness of his true essence and yearns to retrace the path from the multiplicity of his nature to the Oneness from which he originated.

Kabbalah's mission is to help man develop this awareness and turn him onto the path. Four manuscripts in the Hebraic Section touch upon this quest, dealing with dreams and their interpretation; transmigration of souls; healing the soul; and remedies and recipes for such healing. in the Bible, dreams were understood as vehicles for God's communication to man. only the chosen could understand such communication as, for example, Joseph and Daniel, who were the biblical interpreters of dreams par excellence. In Talmudic days, dreams were also interpreted psychologically as windows to the soul through which one might glimpse the dreamer's innermost thoughts and feelings. Said Rabbi Jonathan, "a man is shown in a dream only what is suggested by his own thoughts" (Berakhot 55b).

Maimonides, ever the rationalist, saw dreams as products of the imagination, but the Zohar, the classic text of Jewish mysticism, gives dreams both reality and potency. Among the kabbalists, and particularly in the mystical teachings of Isaac Luria (1534-1572), dreams and their interpretation are of central concern. Thus, Hayim Vital (1543-1620), Luria's chief disciple, fills his spiritual autobiography, Sefer ha-Hezyonot, with dreams and visions.

|

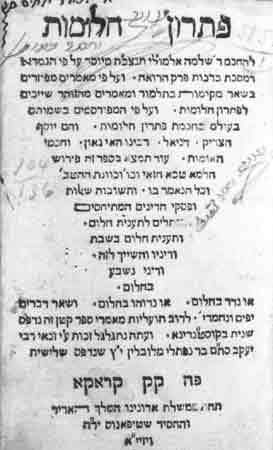

The most popular of the works on dreams was Solomon Almoli's Pitron Halomot (Interpretation of Dreams), first published in Salonica, 1515, as Mefasher Halmin. In full or abridged form it has since been republished at least a dozen times in Hebrew, twice in Yiddish, and twice in Persian translations. Almoli, born in Spain before 1485, lived in Constantinople, where he served as a rabbi and physician. His work is a dissertation on the history of the role of dreams in the Jewish religious tradition, views on the subject drawn from the classical texts of non-Jewish authors, and a handbook for the interpretation of dreams. The Library owns a manuscript version of the work, apparently from the eighteenth century, as well as the rare krakow edition of 1580.

The doctrine of the transmigration of souls, alternately accepted and refuted by Jewish religious leaders and scholars, was raised to a dogma by Kabbalah. Those who upheld it claimed that it was an expression of God's justice and mercy-otherwise how could one explain the suffering of the righteous, the prosperity of the wicked, the suffering of children? Only punishment for sins committed and rewards for righteousness performed in earlier manifestations, in other bodies, could explain such inequities.

Isaac Abrabanel (1437-1508) argued that God in His mercy grants a grievous sinner yet another opportunity for repentance and redemption by affording his soul another life in another body. Even the great suffering inflicted upon the righteous may be an expression of God's mercy, Abrabanel maintains, for it may be a lesser punishment here on earth for sins committed in an earlier manifestation, instead of the justly deserved harsher punishment which would have to be meted out in the next world. To which Leone Modena (1571-1648) countered: Why send the soul into another body for punishment, why could the punishment not have been inflicted on the soul while still in the body which abetted the sin? And would it not be more in keeping with God's mercy to recognize the weakness of the body and to forgive, rather than to punish?

Luria's disciples raised the dogma of transmigration of souls to a science and an art. The concept of "impregnation of souls" permitted a soul that had attained purity in a former life to enter the body of another individual to help his resident soul in its quest for purity. Souls which missed attaining full purity could try for the required "elevation" in a new body, in the process "elevating" another soul. The process took on material and cosmic proportions. The purified souls of Israelites unite with the impure souls of other peoples to free them of their taint and uplift them so that the whole world may come closer to redemption. Hence, the dispersal of Israel is not intended as punishment but as the salvation of humankind.

|

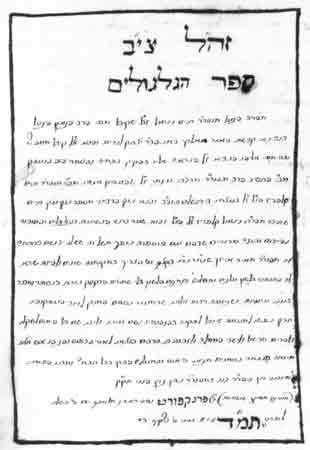

The classic work on transmigration of souls according to Lurianic doctrine is Sefer ha-Gilgulim (Book of Transmigration) by Hayyim Vital of Safed, the recorder — some would say the author — of the teachings of Isaac Luria. This material comprises the fourth section of his magnum opus, Etz Hayyim (Tree of Life). The Library's manuscript is a copy of the first edition of that oft-reprinted work, published in Frankfort-am -Main in 1684. Vital lists a number of contemporaries and the sparks of which souls were united with theirs. The soul of the biblical commentator Moses Alsheikh, he said, was united with that of the Amora Samuel ben Nahman, from which he derived his great talent as a preacher; sixteenth-century Safed kabbalists Moses Cordovera and Elijah de Vidas were such great friends because both shared the soul of the good King Zechariah. The soul of Moses which had once been in the body of Simeon ben Yohai, the "father of Kabbalah," was now in the body of Isaac Luria, who assured his disciple Vital that this soul was one which remained untainted by Adam's sin.

|

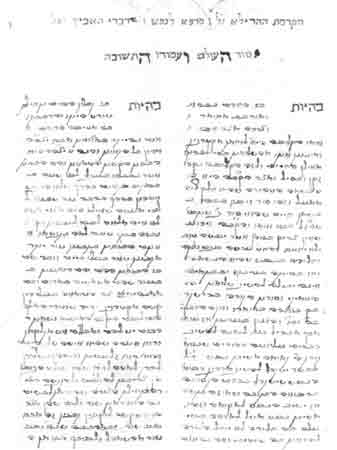

Tainted souls, sinful souls can be cured and uplifted, and the kabbalists provided the means of doing so: the study of sacred texts at propitious times. Thus, Marpe La-Nefesh (Healing for the Soul), compiled by Abraham ben Isaac Zahalon from the teachings of Isaac Luria on ethical behavior and penitence, is "medicine for the soul." Completed in Baghdad in 1593, it was published in Venice in 1595. The Library's manuscript of the work contains Luria's and Zahalon's words in parallel columns.

|

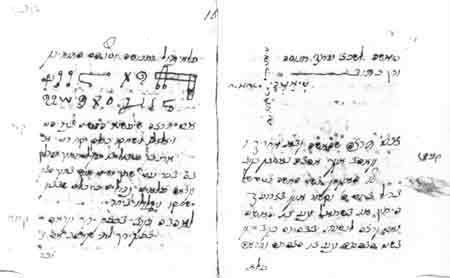

If the soul needed uplifting and healing, so too did the body. For that, there is a manuscript of Sefer Sodot U'Segulot, U'Refuot V'Ta-a lot (A Collection of Secret Formulas, Incantations, Medicines, and Cures) written in Genoa in 1711, which contains 386 "magic formulas for everything from toothache and insomnia to growing hair and improving the memory, from destroying one's enemies to currying favor with the mighty. And there are, of course, many love potions."

Dreams and their interpretation, a prelife of the soul and its psychic consequences, the need and the formulas for the healing of the soulpsyche attest to the centrality of interest in man-not man as a mechanism or as the noblest of all creatures, but man as so unique and complex a being that his essence is different from that of the rest of creation.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).