Women & Jewish Books: Nineteenth-Century Female American Poets

From women publishers, women patrons, and women printers we turn to women authors, and limit ourselves to one place, one time, and one genre of literature. In nineteenth-century America we may seek in vain for one Jewish male we might call a poet, but we do meet four women who gained distinction as poets: Penina Moise (1797-1880) [See also the biography of Moise], Rebekah Hyneman (1812-1875), Minna Kleeberg (1841-1878), and Emma Lazarus (1849-1887) [See also the biography of Lazarus].

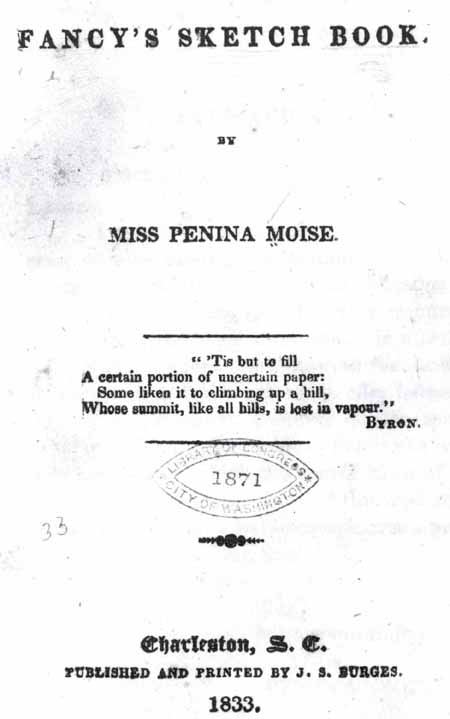

Penina Moise

Born in 1797 in Charleston, S.C., then the largest Jewish community in America, Penina Moise lived there the rest of her life. After her father died when she was twelve, she had no further formal education; nevertheless, she persisted in study and reading and soon turned to writing. Self-taught, she became a widely published writer, her poems and sketches appearing in the Washington Union, New York's The Home Journal, Boston's Daily Times, the New Orleans Commercial Times, Isaac Leeser's The Occident, Godey's Lady's Book, and her hometown newspapers. Members of her large family intermarried and strayed from the faith, but for Penina her religion was the center of her life. For some time she was superintendent of Beth Elohim's Sunday School in Charleston, and after the Civil War, she joined her sister and niece in running a private school. By that time she had gone blind, but she continued her literary activity by dictating poems and essays to her niece.

|

Two books remain to bear witness to her gifts. A collection of her early poetry, Fancy's Sketch Book, was published in Charleston in 1833. Few copies have survived. Looking through the Library's copy, we find verses of general interest and a few of Jewish content, such as "The Hero of Gilead" and "on the Death of My Preceptor Isaac Harby Esq." A poem inviting those who seek freedom to come to these shores, "To Persecuted Foreigners," has a verse which speaks to her Jewish brethren:

If thou art one of that oppressed race,

Whose pilgrimage from Palestine we trace,

Brave the Atlantic--Hope's broad anchor weigh,

A Western Sun will gild your future days.Her poems were soon forgotten, but her hymns continued to be sung. Of the 2 10 hymns in Hymns Written for the Use of Hebrew Congregations, Charleston, which, in the two years 1856 and 1857, went through four editions, 180 are by Penina Moise. A hymn "For the Sick" closes with:

Lengthen out the little span

Of Thy worshipper, O Lord!

Nor, till I reform my plan,

Cleave fore'er the vital cord.As the dial's shadow turned

At the pray'r of Judah's king;

Let not my appeal be spurned,

Save me still Thy praise to sing.In the eighty-third year of her life the vital cord was cloven fore'er. A stanza in one of Miss Moise's hymns might serve as her epitaph:

Lord! To Thee will I adhere

Though condemned in grief to languish

Though the whole of my career

May be spent in tears and anguish.

See I not a better land?

Hold I not a Father's hand?

Rebekah Hyneman

Born in Philadelphia to a Jewish father and Christian mother, Rebekah Gumpert, raised in her father's faith, remained a devout Jew all her life. Following a business failure, her father had to take the family to Bucks County, where there were no facilities for formal education. Like Penina Moise, Rebekah acquired her literary background by individual study, mastering French and German, and later in life, Hebrew. She married Benjamin Hyneman, took his name and reaffirmed his faith as her faith; but when she was five years wed, mother of a son and expecting another child, her married life came to an end. Benjamin never returned from a business trip to the West. It was believed that he was murdered for the valuable jewelry he carried to sell. Rebekah never remarried and took to writing stories, a novelette entitled Woman's Strength, but most of all poems, many published in The Occident. In 18 5 3 a collection of them, The Leper and Other Poems, was published in Philadelphia.

The love for her faith, its people, its holy days and holy places shines through her words. She writes of her biblical namesake:

When thy dark eyes were heaven-ward raised,

Did fires prophetic light thy soul,

And point to thee the weary path,

Thy children tread to win their goal?

Deep in each earnest Jewish heart

Are shrined those memories of the past,

Memories that time can ne'er efface,

Nor sorrow's blighting wing o'ercast.Of "Israel's Trust," she writes:

Borne down beneath insulting foes,

Defamed, dishonored, and oppressed,

Our country fallen and desolate,

Our name a by-word and a jest

Still are we Thine--as wholly Thine

As when Judea's trumpets' tone

Breathed proud defiance to her foes,

And nations knelt before her throne.

We are Thine own; we cling to thee

As clings the tendril to the vine;

Oh! 'mid the world's bewildering maze,

Still keep us Thine, forever Thine!

|

Again and again, her life was scarred by tragedy. Early widowed, she also lost her two sons. Barton suffered long from a fatal disease; Elias Leon, who at twenty-eight volunteered for service in the Civil War, was captured and imprisoned in the dread Andersonville prison. in half a year, cruel treatment and starvation took its toll. These lines she wrote are a fitting epitaph:

Now let me die!

The bloom of earth has passed away--

Its pleasures pall, its flowers decay--

The hopes that lured with dazzling ray,

Low, withered lie.Oh! placid sleep,

I sink at last in thy embrace;

My task is done--a weary race

Was mine on earth; let my resting-place

Be lone and deep.Minna Kleeberg

When Minna Kleeberg arrived in the United States from her native Germany in 1866, she brought with her a reputation as a well-regarded poet. A year earlier she had gained wide recognition for her poem, "Ein Lied vom Salz," a powerful plea for the removal of the Prussian tax on salt. Her poetry expressed devotion to her faith and a passion for social justice.

Daughter of a physician, she received as fine an education as a girl could obtain in mid-nineteenth-century Germany. After her marriage to Rabbi L. Kleeberg, her poetry turned to liturgical creations, while continuing to serve as a vehicle for social expression. Her poetry appeared in a variety of German-language periodicals in Germany and in the United States. Most of her poems were lyrical, some topical-urging the emancipation of women, calling for the broadening of democracy-and some liturgical. A gathering of her poems, Gedichte, was published in 1877 in Louisville, where her husband was serving as rabbi.

Minna Kleeberg was best known to the American Jewish community for her hymns which appeared in the most widely used Jewish hymnal in nineteenth-century America, Isaac M. Wise's Hymns, Psalms and Prayers, In English and German (Cincinnati, 1868). Ten German hymns by Minna Kleeberg form the largest number by any poet. They celebrate the Torah, man, faith, and the holidays.

|

Less than two years after settling in New Haven, to which her husband had been called, she breathed her last on the last day of 1878. In his eulogy for his dear departed wife, Rabbi Kleeberg recalled:

Almost from her childhood she complained of the subordinate position which tradition and custom assigned to woman. Upon her thirteenth birthday and the following Sabbath she shed bitter tears that she was not, like Jewish boys of her own age, entitled to take part in the public reading of the law, and by this rite be solemnly consecrated to the cause of Israel ... The vindictive accusations of Richard Wagner ... she met in a widely circulated paper, with a few bristling articles. Her poetical effusions, as well as her bold and vigorous defence of her co -religionists, were acknowledged by many letters of appreciation from all quarters, even from the other side of the ocean. The Crown Prince of Prussia, the Chancellor Bismarck, Edward Lasker ... The departed was a poet by the grace of God.

Emma Lazarus

|

The leading Jewish literary figure by far in nineteenth-century America was the poet Emma Lazarus. Her sonnet, "The New Colossus," engraved on the base of the Statue of Liberty, has assured her a measure of immortality. More will be said of her later. For now, let the stanza of one of her poems suffice, a poem for the New Year 5643 (1882-83), which saw the onset of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe to Palestine and to America:

In two divided streams the exiles part,

One rolling homeward to its ancient source,

One rushing sunward with fresh will, new

heart.

By each the truth is spread, the law

unfurled,

Each separate soul contains the nation's

force,

And both embrace the world.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).