|

The Republic of Turkey, a transcontinental country located mostly on Anatolia in Western Asia and East Thrace in Southeastern Europe, has a Jewish history dating back possibly to the 4th century B.C.E. Today the Jewish population of Turkey is approximately 18,500, with 17,000 Jews living in Istanbul.

- Early History

- A Haven for Sephardic Jews

- The Life of Ottoman Jewry

- Equality & A New Republic

- Turkish Jewry Today

- Jewish Education, Language & Social Life

Early History

At midnight August 2, 1492, when Columbus embarked on what would become his most famous expedition to the New

World, his fleet departed from the relatively unknown seaport of Palos

because the shipping lanes of Cadiz and Seville were clogged with Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain by the Edict of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand

of Spain.

The Jews forced either to convert to Christianity

or to "leave" the country under menace "they

dare not return... not so much as to take a step on them not trespass

upon them in any manner whatsoever" left their land, their

property, their belongings all that was theirs and familiar to them

rather than abandon their beliefs, their traditions, their heritage.

In the faraway Ottoman Empire, one ruler - Sultan Bayazid II- extended an immediate welcome to the persecuted

Jews of Spain, the Sephardim.

The history of the Jews in Anatolia, however, started many

centuries before the migration of Sephardic Jews. Remnants of Jewish settlement from the 4th century B.C.E. have

been uncovered in the Aegean region, where Jews lived and traded in

the ancient cities of Ephesus, Sardis, Pergamon, and Smyrna (renamed

Izmir by the Turks). The historian Josephus

Flavius relates that Aristotle "met Jewish people with

whom he had an exchange of views during his trip across Asia Minor."

Second and third century Greek inscriptions tell

of a flourishing Jewish community in Smyrna. Ancient synagogue ruins have also been found in Sardis, near Izmir, dating from 220

B.C.E. and traces of other Jewish settlements have been discovered

near Bursa, in the southeast and along the Aegean, Mediterranean and

Black Sea coasts. A bronze column found in Ankara confirms the rights

the Emperor Augustus accorded the Jews of Asia Minor.

Jewish communities in Anatolia flourished and continued

to prosper through the Turkish conquest. When the Ottomans captured

Bursa in 1324 and made it their capital, they found a Jewish community

oppressed under Byzantine rule. The Jews welcomed the Ottomans as saviors. Sultan Orhan gave

them permission to build the Etz ha-Hayyim (Tree of Life) synagogue

which remained in service until 50 years ago.

Early in the 14th century, when the Ottomans had

established their capital at Edirne, Jews from Europe, including Karaites, migrated there.1 Similarly, Jews expelled from Hungary in 1376, from France by

Charles VI in September 1394, and from Sicily early in the 15th century

found refuge in the Ottoman Empire. In the 1420s, Jews from Salonika

then under Venetian control fled to Edirne.2

Ottoman

rule was much kinder than Byzantine rule had been. In fact, from

the early 15th century on, the Ottomans actively encouraged Jewish immigration.

Western European Jews received three invitations to settle in the Ottoman

Empire. Two were from Muslim sultans, Muhammad (Mehmet) II in the middle

of the 15th century and Bayazid II in 1492. The third came in a letter

sent by Rabbi Yitzhak Sarfati (from Edirne) in 1454 to Jewish communities

in Europe in the first part of the century that "invited his

coreligionists to leave the torments they were enduring in Christiandom

and to seek safety and prosperity in Turkey."3 Rabbi Sarfati wrote that “here every man dwells at peace under

his own vine and fig tree.”3

When Mehmet II "the Conqueror" took Constantinople

in 1453, he encountered an oppressed Romaniot (Byzantine) Jewish community

which welcomed him with enthusiasm. Sultan Mehmet II issued a proclamation

to all Jews "... to ascend the site of the Imperial Throne,

to dwell in the best of the land, each beneath his Dine and his fig

tree, with silver and with gold, with wealth and with cattle...".4

In 1470, Jews expelled from Bavaria by Ludvig X found

refuge in the Ottoman Empire.5

A Haven for Sephardic Jews

Sultan Bayazid II's offer of refuge gave new hope

to the persecuted Sephardim. In 1492, the Sultan ordered

the governors of the provinces of the Ottoman Empire "not

to refuse the Jews entry or cause them difficulties, but to receive

them cordially."6 According

to Bernard Lewis, "the Jews were not just permitted to settle

in the Ottoman lands, but were encouraged, assisted and sometimes

even compelled".

Immanual Aboab attributes to Bayazid II the famous

remark that "the Catholic monarch Ferdinand was wrongly considered

as wise, since he impoverished Spain by the expulsion of the Jews,

and enriched Turkey."7

The arrival of the Sephardim altered the structure

of the community and the original group of Romaniote Jews was totally

absorbed.

Menorah with Crescent & Star (Izmir) Menorah with Crescent & Star (Izmir) |

These Jews settled in various Ottoman cities, such as

Salonika, but it was not until the late sixteenth century that they

moved to Smyrna, which has become a major port city. The arrival of

the Sephardim altered the structure of the community and the original

group of Romaniote Jews (descendants of Greek-speaking Jews) was totally

absorbed.

Over the centuries an increasing number of European Jews,

escaping persecution in their native countries, settled in the Ottoman

Empire. In 1537 the Jews expelled from Apulia (Italy) after the city

fell under Papal control, in 1542 those expelled from Bohemia by King

Ferdinand found a safe haven in the Ottoman Empire.8 In March of 1556, Sultan Suleyman "the Magnificent" wrote a letter to Pope Paul

IV asking for the immediate release of the Ancona Marranos, which he

declared to be Ottoman citizens. The Pope had no other alternative than

to release them, the Ottoman Empire being the "Super Power"

of those days.

By 1477, Jewish households in Istanbul numbered 1,647

or 11% of the total. Half a century later, 8,070 Jewish houses were

listed in the city.

The Life of Ottoman Jewry

For 300 years following the expulsion, the prosperity

and creativity of the Ottoman Jews rivaled that of the Golden Age

of Spain.

Four Turkish cities: Istanbul, Izmir, Safed and Salonica became the

centers of Sephardic Jewry. The Tu

B’Shevat seder was developed in Izmir in the seventeenth

century. The creator may have been Shabetai

Zvi, the pseudo Messiah and founder of the Sabbatean movement. In reaction to Zvi, Izmir's

Jews withdrew from any secular pursuits.

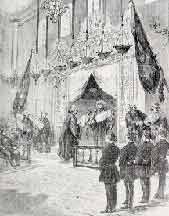

Left:

Jewish Doctor - 1568 (Woodcut from "Nicolay de Nicolay",

page 185); Right: Prayer offered for the Victory of Turkish

armies in the war against Russia with the presence of the Sadrazam

(Prime Minister) Ibrahim Edhem Pasha Ahrida Synagogue (London

Illustrated News 9.6.1877) Left:

Jewish Doctor - 1568 (Woodcut from "Nicolay de Nicolay",

page 185); Right: Prayer offered for the Victory of Turkish

armies in the war against Russia with the presence of the Sadrazam

(Prime Minister) Ibrahim Edhem Pasha Ahrida Synagogue (London

Illustrated News 9.6.1877)

|

Most of the court physicians were Jews: Hakim Yakoub,

Joseph and Moshe Hamon, Daniel Fonseca, Gabriel Buenauentura to name

only very few ones.

One of the most significant innovations that Jews brought

to the Ottoman Empire was the printing press.

In 1493, only one year after their expulsion

from Spain, David & Samuel ibn Nahmias established the first

Hebrew printing press in Istanbul.

Ottoman diplomacy was often carried out by Jews. Joseph Nasi, appointed the Duke

of Naxos, was the former Portuguese Marrano Joao Miques. Another Portuguese

Marrano, Aluaro Mandes, was named Duke of Mytylene in return of his

diplomatic services to the Sultan. Salamon ben Nathan Eskenazi arranged

the first diplomatic ties with the British Empire. Jewish women such

as Dona Gracia Mendes

Nasi "La Seniora" and Esther Kyra exercised considerable

influence in the Court.

In the free air of the Ottoman Empire, Jewish literature

flourished. Joseph Caro compiled the Shulkhan Arukh. Shlomo haLevi Alkabes composed the Lekhah Dodi a hymn which welcomes the Sabbath according to both Sephardic and Ashkenazi ritual. Jacob Culi began

to write the famous MeAm Loez. Rabbi Abraham ben Isaac Assa became

known as the father of Judeo-Spanish literature.

On October 27, 1840 Sultan Abdulmecid issued his famous

ferman concerning the "Blood Libel Accusation" saying: "... and for the love we bear to our subjects, we cannot permit

the Jewish nation, whose innocence for the crime alleged against them

is evident, to be worried and tormented as a consequence of accusations

which have not the least foundation in truth...".

Under Ottoman tradition, each non-Moslem religious community

was responsible for its own institutions, including schools. In the

early 19th century, Abraham de Camondo established a modern

school, "La Escola", causing a serious conflict between

conservative and secular rabbis which was only settled by the intervention

of Sultan Abdulaziz in 1864. The same year the Takkanot haKehilla (By-laws of the Jewish Community) was published, defining the structure

of the Jewish community.

Equality & A New Republic

Efforts at reform of the Ottoman

Empire led to the proclamation of the Hatti Humayun in 1856, which

made all Ottoman citizens, Moslem and non-Moslem alike, equal under

the law. As a result, leadership of the community began to shift away

from the religious figure to secular forces.

World War I brought to an end the glory of the Ottoman

Empire. In its place rose the young Turkish Republic. Mustafa Kemal

Ataturk was elected president, the Caliphate was abolished and a secular

constitution was adopted.

"Etz

ha-Hayim" Synagogue before it burnt in 1941. Visit of late

Chief Rabbi Haim Bedjerano. (Ortakoy - Istanbul) |

Recognized in 1923 by the Treaty of Lausanne as a

fully independent state within its present-day borders, Turkey accorded

minority rights to the three principal non-Moslem religious minorities

and permitted them to carry on with their own schools, social institutions

and funds. In 1926, on the eve of Turkey's adoption of the Swiss Civil

Code, the Jewish Community renounced its minority status on personal

rights.

During the tragic days of World War II, Turkey managed

to maintain its neutrality. As early as 1933 Ataturk invited numbers

of prominent German Jewish professors to flee Nazi

Germany and settle in Turkey. Before and during the war years,

these scholars contributed a great deal to the development of the

Turkish university system.

During World War II, Turkey served as a safe passage

for many Jews fleeing the horrors of the Nazism.

While the Jewish communities of Greece were wiped out almost completely by Hitler,

the Turkish Jews remained secure. Several Turkish diplomats, Ambassadors

Behic Erkin and Numan Menemencioglu; Consul Generals Fikret Sefik

Ozdoganci, Bedii Arbel, Selahattin Ulkumen; Consuls Namik Kemal Yolga

and Necdet Kent, just to name a few, spent all their efforts to save

from the Holocaust the Turkish Jews in those countries, and

succeeded.9 Mr. Salahattin Ulkumen, Consul

General at Rhodes in 1943-1944, has been recognized by the Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile ("Hassid Umot

ha'Olam") in June 1990. Turkey continues to be a shelter, a haven

for all those who have to flee dogmatism, intolerance and persecution.

Turkish Jewry Today

Left:

"Rimonim" with Crescent & Star (Izmir - Istanbul). Right: House bearing both "Magen David" and

Moslem "Mashallah" (Galata - Istanbul)

|

The present (2016) size of Jewish Community is estimated

at around 18,500, out of a total population of 70 million. This is a small number compared to the 80,000 Jewish individuals who lived in Turkey at the time of Israel's establishment. The vast

majority, about 17,000, live in Istanbul, with a community of about

1,500 in Izmir and other smaller groups located in Adana, Ankara,

Bursa, Canakkale, Iskenderun and Kirklareli. Sephardis make up 96% of the Community, with Ashkenazis accounting for the rest. There are about 100 Karaites, an independent group that

does not accept the authority of the Chief Rabbi.

Turkish Jews are legally represented, as they have

been for many centuries, by the Hahambasi, the Chief Rabbi. The Chief Rabbi is assisted in his affairs by a religious

Council made up of a Rosh Bet Din and three Hahamim. Rav David

Asseo held the position of Chief Rabbi from 1961 until his death in 2003. The current Chief Rabbi of Turkey is Ishak Haleva, who held the position of Rav David's Asseo's deputy for seven years before his death. Thirty-five Lay

Counselors look after the secular affairs of the Community and an

Executive Committee of fourteen, the president of which must be elected

from among the Lay Counselors, runs the daily affairs.

Synagogues are classified as religious foundations (Vakifs). There are 19 active

synagogues in Turkey, 16 of which are in Istanbul, and 6 rabbis. Three are in service

in holiday resorts, during summer only. Some of them are very old,

especially Ahrida Synagogue in the Balat area, which dates from middle15th

century. The 15th and 16th century Haskoy and Kuzguncuk cemeteries

in Istanbul are still in use today. There are eleven Kosher butcher shops, a Jewish newspaper, and two exclusively Jewish senior living facilities in Turkey.

In October 2013, Nesim Güveniş, deputy chairman the Association of Turkish Jews in Israel, reported that hundreds of young Turkish Jews were emigrating to the United States or Western Europe triggered by increased anti-Semitism led by the Turkish government. The negative atmosphere in the country towards Jews and Israel emerged with the rise of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and was aggravated by the deadly Gaza Flotilla incident in 2010. Turkey has experienced underlying anti-semitism for much of it's history but the anti-semitic ideals really started to show in public after Erdogan's rise to power. Erdogan's government platform comes from a strict Islamist ideology. Anti-semitic sentiments are common in Turkey, with the most recent (2015) Anti-Defamation League Global 100 index of anti-semitism concluding that 69% of Turks hold some sort of anti-semitic beliefs. This figure is significantly higher than other European averages and only slightly lower than the Middle East average. Scholar in Turkish minorities Rifat Bali has spent years of his life dedicated to studying the Jewish community in Turkey, and makes the claim that although Jews have a historical presence in Turkey they have never been accepted as full citizens, by the country that claims to be secular. Turkey may put on a farce of being secular, but according to Bali anyone who is a non-Muslim is not welcomed warmly into Turkish arms.

Jews in Turkey have been the victims of senseless violence directed at them because of their religion on multiple occasions. In September 1986 a member of the Palestinian terror group Abu Nidal opened fire on Jewish worshipers participating in services at the Neve Shalom synagogue in Istanbul, killing 22 Jewish individuals. Neve Shalom synagogue was again the target of a terror attack in November 2003 when multiple truck bombs went off all around Istanbul, one exploding in front of Neve Shalom and another exploding in front of Bet Israel congregation. The blasts killed 57 and injured over 700.

The Anti-Defamation League's global index of antisemitism has demonstrated that Turkey harbors more antisemitic sentiments than Iran and most other Middle-Eastern countries. The 2014 survey found that 75% of Turkish citizens believe that Jewish individuals have too much power in the business world, and also found that 69% of Turkish citizens believe that Jewish Turks are more loyal to Israel than to Turkey. According to Turkish politician Aykan Erdemir antisemitism, hate crimes, discrimination, hate speeches, and violence directed at minorities are all on the rise in Turkey, and this creates a hostile environment for the few thousand Jews left there.

In mid 2014 Operation Protective Edge sparked worldwide criticism of Israel's actions. During and after the operation, over 30,000 Turkish language tweets were published that stated positive things about Hitler and the attrocities he committed against the Jews during the Holocaust. A popular Turkish pop music singer with over 500,000 followers, Yildiz Tilbe, tweeted the message "May God Bless Hitler".

Despite this increasingly anti-semitic environment, Jews are not choosing to flee to Israel. Only 74 Jews made Aliyah to Israel from Turkey in 2013. Jews looking to escape Turkey have turned to the United States and Eastern European countries for a new begining instead of Israel.

A Pew Research Center Poll released in November 2014 detailed the true feelings of the Turkish population towards Israel. According to the poll, 86% of Turkish citizens hold a negative view of Israel, with only 2% of Turkish individuals viewing Israel in a positive light. Out of the nine countries in the survey, including Israel, Russia, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and others, Israel was viewed as the least favorable followed by Iran. Of the choices offered, Turks said that they have the most positive view of Saudi Arabia.

After a 5-year, $2.5 million restoration project, in March 2015 the Great Synagogue in Edirne was reopened after over 40 years of decay. In the Great Synagogue's heyday after it opened in 1909, it served a population of approximately 20,000 Jews. Thousands of Jews fled the town of Edirne in 1934 following a mob attack against the population, but many remained and rebuilt their lives. The Great Synagogue was the first temple to open in Turkey in two generations. As of it's reopening the Synagogue does not serve a congregation, and serves most of the time as more of a museum than a functioning place of worship. In 2015, there were only three Jewish families left in the town of Edirne.

The island of Buyukada, Turkey is a beautiful summer getaway for all Turks, but the island is especially popular with Jews. During the summer months, 4,000+ of the 17,000 Jews living in Turkey flock to the island paradise for vacation and relaxation. The island boasts two kosher butchers and a kosher restaurant, along with various other services and shops.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan commented on the recent improvement of relations between Turkey and Israel in December 2015, stating that, “this normalization process has a lot to offer to us, to Israel, to Palestine and also to the region... The region needs this.” Turkey-Israel relations had been strained since the 2010 Gaza Flotilla Incident, in which nine Turkish citizens were killed.

Turkish citizens celebrated Hanukkah in a public display for the first time, on December 14, 2015. Turkish Jews lit a large menorah in Istanbul’s historical Ortakoy Square, and traditional Hanukkah blessings were recited via loudspeaker. The head of Turkey's Jewish community, Ishak Ibrahimzadeh, spoke at the event, which was attended by many government officials. In a statement released on December 7, Turkey's President Erdogan commented, “I wish peace, happiness and welfare to all Jews, primarily Turkey’s Jewish citizens who are an inseparable part of our society, on the occasion of Hanukkah.”

The Istopol Synagogue in Istanbul was vandalized in January 2016, following the first service held in the building in 65 years. “Terrorist Israel, there is Allah,” was scrawled on an outer wall of the building in white paint. The synagogue, located in a majority Jewish neighborhood, goes largely unused.

Modern Jewish Education, Language & Social Life

|

|

Left:

Turkish Crescent & Star on the top of the Ehal "La

Sinyora" Synagogue (Izmir). Right: Ankara Synagogue |

Most Jewish children attend state schools or private Turkish or

foreign language schools, and many are enrolled in the universities.

Additionally, the Community maintains a primary school for 300 pupils

and a secondary school for 250 students in Istanbul, and an elementary

school for 140 children in Izmir. Turkish is the language of instruction,

and Hebrew is taught 35 hours a week.

While younger Jews speak Turkish as their native

language, the older generation is more at home speaking in French

or Judeo-Spanish (Ladino). A conscious effort is spent to preserve

the heritage of Judeo-Spanish

For

long years Turkish Jews have had their own press. La Buena Esperansa

and La Puerta dew Oriente started in Izmir in 1843 and Or Israel started

to be published in Istanbul ten years later. Now one newspaper survives:

SALOM (Shalom), an eight-page weekly with seven pages written in Turkish

and one in Judeo-Spanish.

A Community Calendar (Halila) is published by the

Chief Rabbinate every year and distributed free of charge to all those

who have paid their dues (Kisba) to the welfare bodies. The Community

cannot levy taxes, but can request donations.

Two Jewish hospitals the 98 bed Or haHayim in Istanbul

and the 22 bed Karatas Hospital in Izmir serve the Community. Both

cities have homes for the aged (Moshav Zekinim) and several welfare

associations to assist the poor, the sick, the needy children and

orphans.

Social clubs containing libraries, cultural and sports

facilities, discotheques give young people the chance to meet.

The Jewish Community is a very small group in Turkey

today, considering that the total population which is 99% Moslem exceeds

57 million. But in spite of their number the Jews have distinguished

themselves. There are several Jewish professors teaching at the universities

of Istanbul and Ankara, and many Turkish Jews are prominent in business,

industry and the liberal professions.

Contacts

Chief Rabbinate of Turkey

Yemenici Sokak 23 Beyoglu, Istanbul

Tel. 90 212 244 8794

Fax. 90 212 244 1980

Israeli Embassy

Mahatma Gandhi Sok. 85, Ankara

Tel. 90 312 446 3605, Fax. 90 312 426 1533

Beth Israel Synagogue

265 Mithatpasa Street

Karatas

Izmir, Turkey

Sources:

Guleryuz, Naim Avigdor. “The Turkish Jews: 700 Years of Togetherness”, Gozlem (2009);

The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study

of Contemporary Anti-Semitism and Racism, Annual Report 2005 - Turkey;

Encyclopaedia

Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group.

All Rights Reserved;

“Poll: Turkish People Dislike Israel Slightly More Than ISIS, Hezbollah, Hamas,” Haaretz (November 3, 2014);

Jean Yackley, Ayla. “Turkey unveils Great Synagogue as Jewish population fades,”Reuters (March 25, 2015);

“Reconciliation pact struck with Turkey: Israel,” Yahoo News (December 17, 2015)

(1) Mark Alan Epstein, "The

Ottoman Jewish Communuties and their role in the 15th and 16th centuries"

(2) Joseph Nehama, "Histoire

des Israelites de Salonique"

(3) Bernard Lewis, "The Jews

of Islam"

(4) Encyclopedia Judaica,

Volume 16 page 1532

(5) Avram Galante, "Histoire

des Juifs d'lstanbul", Volume 2

(6) Abraham Danon, in the Review

Yossef Daath No. 4

(7) Immanual Aboab, "A Consolacam

as Tribulacoes de Israel, III Israel"

(8) H. Graetz, "History of

the Jews"

(9) Immanual Aboab, "A Consolacam

as Tribulacoes de Israel, III Israel"

|