Witnesses to History: A Choice Sampling

Witnesses to history, too, are some exotic morsels of special interest to bibliophiles, historians, and collectors. Only Venice might justifiably dispute the claim that Amsterdam was the greatest center of Hebrew printing. The first book printed in Amsterdam would then be of singular interest to bibliophiles. The colophon to Sefer Shvilei Emunah (Paths of Faith), by Meir Ibn Aldabi, printed by Daniel da Fonseca, states: "Praised be the Lord who gives strength to the weary ... who helped me complete this heavenly work, first product of (Hebrew) printing in this city." Authorities on Hebrew typography nonetheless award primacy to Seder T'filoth K’Minhag K.K. Sefarad, a Sefardi prayer book published by Menasseh ben Israel, which came off the press on January 1, 1627, a few months before the Fonseca publication. it may well be that work on Fonseca's book began first, but took a longer time to produce because of the inefficiency of its printer. Its editor Abraham da Fonseca, found no less than one hundred printer's errors! Daniel da Fonseca published only one more book, while Menasseh ben Israel's press flourished for a quarter of a century.

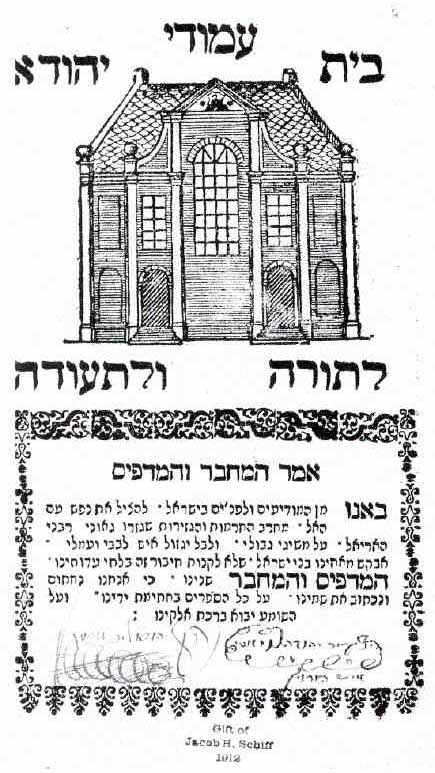

Some three dozen Hebrew books have appeared with the notation that space was being left in each copy for the signature of the author, editor, or publisher. One such volume, Sefer Amudei Bet Yehudah (The Pillars of the House of Judah) Amsterdam, 1766, calls for the signatures of both author and publisher. Both author and printer clearly ask purchasers to buy only copies which have both signatures, yet most extant copies lack the author's. The Library's copy has both that of author Judah ben Mordecai ha-Levi Hurwitz, and of the publisher-printer Yehudah Leib Susmans. This work also has the distinction of bearing the approbation of Moses Mendelssohn, the only Hebrew book so honored.

| |

|

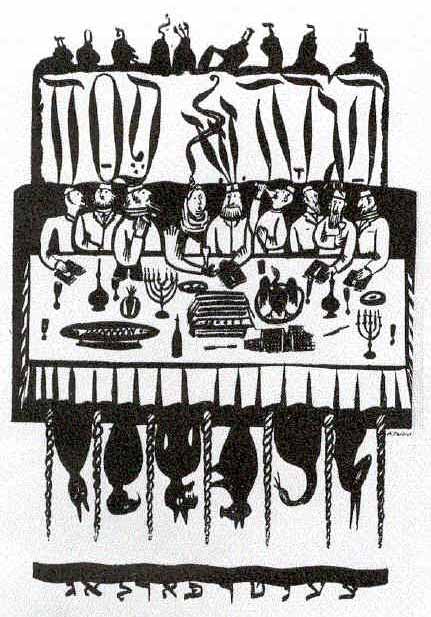

Two books published 120 years apart, one in Amsterdam in 1687, the other in Mexico in 1807, are joined together by language. The former, Seder B'rachot (Order of Benedictions), in Hebrew with a Spanish translation, is a compendium of benedictions and liturgical selections as well as some laws generally not found in the prayer book. Its brief Hebrew introduction is a dedication to Isaac Aboab, a wealthy East India merchant and a patron of rabbinical works, who was himself a scholar and writer. Aboab's father fled from the Inquisition in Mexico and reverted to Judaism in Amsterdam, taking the name Mattathias. Benjamin Senior Godines, publisher of the compendium, found the house of Isaac Aboab "filled with books; rare printed volumes, as well as manuscripts," among them this work, which he calls in Spanish, Orden de Benedictiones. The Spanish was intended for former Marranos or their descendants, who were still not at home in the Hebrew language. The last two benedictions are forms of memorial prayers, with places for the insertion of a name and with proper pronouns for a man and for a woman "who was burned at the stake for the sanctification of the Holy Name ... may the Lord seek recompense for his/her blood, and visit retribution on the enemy."In Mexico, in 1807 the editor of La Gazeta, Don Juan Lopez Cancelada, published a volume with some curious illustrations, Decreto de Napokon ... Sobre Los Judios. One illustration accompanies an account of divorce in Poland "en tiempo de Casimiro," i.e., King Casimir the Great (1310-1370) the legendary protector and benefactor of the Jews. The Jewish woman wears a headdress which seems to be a version of a large phylactery. The four other illustrations are of Jews being tortured by the inquisition.

|

From the manuscript collection in the Library's Hebraic Section, we call attention to two thick volumes of the classic of Lurianic Kabbalah, the Sefer Etz Hayim of Hayim Vital; to a ledger of the Jewish community of Mantua for the years 1784-96, which lists the distribution of honors and contributions to charity; and to a collection of prayers for Simhat Torah, Shavuot, and the ceremony of Brith Milah (circumcision). Also included is a contingent decree of separation and support payments issued in 1880 by the rabbinic court of Constantinople and endorsed and countersigned by the Hakham Bashi (Chief Rabbi). Here the husband is accused of cursing and abusing his wife, reviling her parents, and raising his hand to do her harm. intermediaries attest that the husband has promised to mend his ways but, in the meantime, he is obligated to support her, even while they are separated. We find a report of the injury suffered in 1809 by Rachel Cavalieri, who went up to the attic to watch a balloon flight and fell off a chair. And, to end on a happy note, there is a doily with a dedication to Rabbi Adolf Jellinek (of Vienna) on his seventieth birthday, June 24, 189 1, inscribed by his student Zeev Wolf Sbrieser.

The company of collectors of Haggadot is large and enthusiastic, and the Library houses a collection worthy of their patronage. We cite a few of uncommon historic interest and a few which are not what they seem. The first Haggadah with a French translation was published in 1818 in Metz. Its translator is David Drach, rabbi, doctor of law, a graduate of the Faculty of Letters of the Academy of Paris. He was also the son-in-law of Rabbi Emanuel Deutz, the Grand Rabbi of France. Four years later, Drach converted to Roman Catholicism and persuaded his brother-in-law, the Chief Rabbi's son, to do likewise. In his later years the latter returned to the Jewish faith but Drach remained loyal to and active in his new faith—translating, editing, and writing. Among his works are conversionary tracts and Hebrew poems in honor of the Pope and Cardinals. For obvious reasons not many copies of his translation of the Haggadah have survived.

In Vilna, in 1852 and again in 1860, editions of the Haggadah were published with the commentaries of Zvi Hirsch of Grodno and Jacob of Dubno "arranged according to the custom of Rabbi Elijah Gaon," but severely self-censored. The portion of "This is the bread of affliction" that reads "this year we are slaves, next year we shall be free," is altered to read, "this year we are slaves in many places, next year we shall be free as we are in this our land." The section, "Pour out thy wrath upon the nations which have not known thee, and upon the kingdoms which have not called upon thy Name; for they have devoured Jacob and laid waste his dwelling place" is completely eliminated.

|

A Haggadah called Gufo shel Pesah, etc. (The Essence of Passover or a Haggadah for Jewish Tots), Berlin, 1830, in Hebrew and Yiddish, is not what it purports to be, but is instead a missionary tract "published . . . to rouse the hearts of Jewish children to seek the path of salvation." Nor is the Hagodeh far Gloiber un Apikorsim, published in Moscow, 1927, for "Believers and Atheists," the Passover Haggadah. It, too is a missionary tract, but of a different order. It proclaims, "May all the aristocrats, bourgeois ... Bundists, Zionists ... Poale Zion ... be consumed in the fire of revolution.... May annihilation overcome all the outdated rabbinic laws and customs." An anarchist Haggadah published in New York in the 1890s is of a similar nature.

The Haggadah Shel Pesah, printed in Munich, 1947, is what it proclaims to be, a photo-offset edition of the traditional Haggadah with an English translation. It was published and distributed in Germany by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee for the survivors of the Holocaust, who could now proclaim, "This year we are free ... Next year, in Jerusalem."

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).