From Sea to Shining Sea: Within the Community

The internal communal life of Philadelphia and New York Jewry is revealed by the Constitution and By-Laws of the Jewish Foster Home Society of the City of Philadelphia, 1855, which was organized and run by the leading ladies of the community; and by the Constitution and By-Laws of the Hebrew Benevolent Society of the City of New York, New York, 1865, then in its forty-third year of service as the umbrella organization for Jewish charities.

We note with special satisfaction that the Library of Congress has a copy of Substance of Address on Laying the Corner Stone of the Synagogue “Temime Dereck, ” New Orleans, 1866. The address was by Philip Phillips (1807-1884), who had served as a member of the House of Representatives from Alabama, 1854-55. His participation in a synagogue celebration is one of the first, if not the first, by a Jew who had served in the U.S. Congress.

|

Phillips's participation in Jewish life began early. At age eighteen, he was one of the founding members of the Reformed Society of Israelites in his native Charleston, South Carolina, and served as its secretary at age twenty-one. In 1856, as a resident of Washington, D.C., he contributed ten dollars to the city's Hebrew Congregation towards purchase of a Torah scroll. A year later he served as spokesman for a Baltimore delegation which had come to call upon President Buchanan to protest against a commercial treaty with Switzerland permitting Swiss cantons to discriminate against American Jews who might be visiting there.

Phillips was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1828, then moved to Mobile, Alabama, where, in 1834, he was elected to the state legislature and became a leading political figure. In 1853, he was elected to Congress, and when his term ended he remained in Washington to practice law before the Supreme Court.

|

Because of his wife's pronounced Southern sympathies (she was the former Eugenia Levy of Charleston), they had to leave the city during the Civil War and settled in New Orleans. In his consecration address, Phillips voiced the universalistic sentiments of his first Jewish affiliation, the Reformed Society of Israelites:

I look into the future ... I see the coming day, radiant in glory ... in which, though differing in creed and forms of worship, the voices of all shall unite in the grand anthem, “Hear, 0, Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One!”

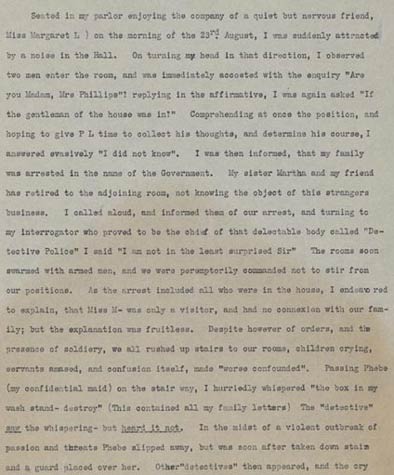

The Phillips Papers housed in the Library's Manuscript Division contain a brief autobiographical sketch, called “A Summary of the Principle Events of My Life,” and two works by his wife. One is a diary entitled “Journal of Mrs. Eugenia Phillips,” the other a memoir, “A Southern Woman's Story of Her Imprisonment During the War of 1861-62.” A fiery and outspoken Confederate sympathizer, Eugenia often found herself at odds with Union officials. In the journal page below, Phillips describes the indignities of her confinement after her arrest by federal officers in Washington, along with two daughters and her sister Martha, on August 23, 1861. Released after a three-week imprisonment, Phillips relocated to New Orleans, where she mocked the funeral of a Union soldier, thereby running afoul of the notorious General Benjamin “Beast” Butler, who issued a special order imprisoning her at Ship Island, where conditions were harsh and primitive.

|

Eugenia Phillips (1819-1902). [Journal kept August 23, 1861-September 26, 1861]. Diary page, August 28, 1861. Manuscript Division |

Philip's writings are staid and proper, Eugenia's, fiery and dramatic. Because of his legal and oratorical skills, he sat in Congress; because of her intense Southern loyalties, she languished in “Beast” Butler's prison. After the war both returned to Washington, where Phillips resumed his law practice and became one of the capital's leading attorneys. He died in 1884 and was buried in the Levy family plot in the Jewish cemetery of Savannah, Georgia.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).