Father Abraham [Lincoln] & the Children of Israel: President Lincoln’s Jewish Friends

Lincoln: And so the Children of Israel were driven from the happy land of Canaan.

Kaskel: Yes, and that is why we have come to Father Abraham, to ask his protection.

Lincoln: And this protection they shall have at once.

Cesar J. Kaskel, apprising President Lincoln of General Grant's Order Number 11

In his scholarly study of American Jewry and the Civil War (Philadelphia, 1951), Bertram W. Korn writes that in the eulogy Rabbi Isaac M. Wise delivered after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, he claimed: "the lamented Abraham Lincoln believed himself to be bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh. He supposed himself to be a descendant of Hebrew parentage. He said so in my presence." There is no shred of evidence to substantiate Wise's assertion, Korn declares, and "Lincoln is not known to have said anything resembling this to any of his other Jewish acquantances." But, Korn asserts, Lincoln "could not have been any friendlier to individual Jews, or more sympathetic to Jewish causes, if he had stemmed from Jewish ancestry." He also points to the Robert Todd Lincoln Collection of Lincoln Papers in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress as a prime source "for the elucidation of Lincoln's contacts with various Jews ... in particular ... Abraham Jonas and Isachar Zacharie."

Some of the "elucidation" Korn mentions may be gathered from sixteen items, eight in manuscript and eight in print, garnered from the Library's rich lode of Lincolniana.

Correspondence with the President

In 1860, Lincoln wrote to Abraham Jonas (1801-1864) "you are one of my most valued friends." The friendship began soon after Jonas settled in Quincy, Illinois, in 1838. He came from Kentucky where he had lived for ten years, served in the State Legislature for four terms, and become the Grand Master of the Kentucky Masons. Before that he lived in Cincinnati; to which he came from England in 1819, to join his brother, Joseph, the first Jewish settler there. In Quincy, Jonas kept store and studied law, which became his lifelong calling. From 1849 to 185 1, he served as postmaster and in 1861 was reappointed to that office by Lincoln. Two letters from the Jonas-Lincoln correspondence in the Library's collection are especially illuminating.

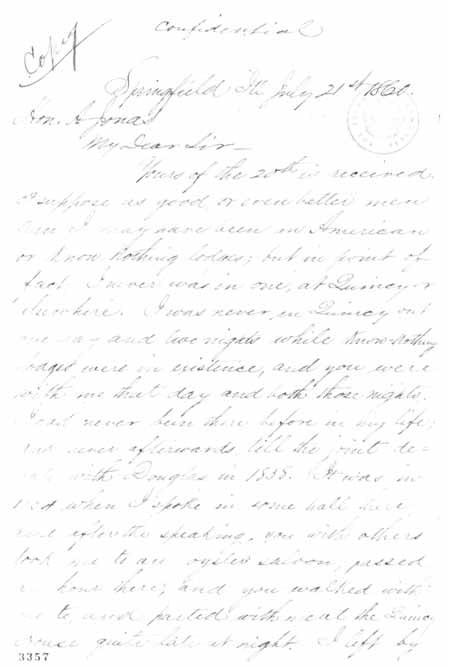

When Lincoln visited Quincy in 1854, he spent most of his time with Jonas, as we can see from his letter to Jonas on July 21, 1860. What occasioned Lincoln's letter was one from Jonas in which he told the presidential candidate: "I have just been creditably informed, that Isaac N. Morris is engaged in obtaining affidavits and certificates of certain Irishmen that they saw you in Quincy come out of a Know Nothing Lodge." Jonas feared that this purported association with a nativist antiforeigner political party would cost Lincoln many immigrant votes, so he alerted his friend in a "confidential" letter. Lincoln's lengthy reply states, in part:

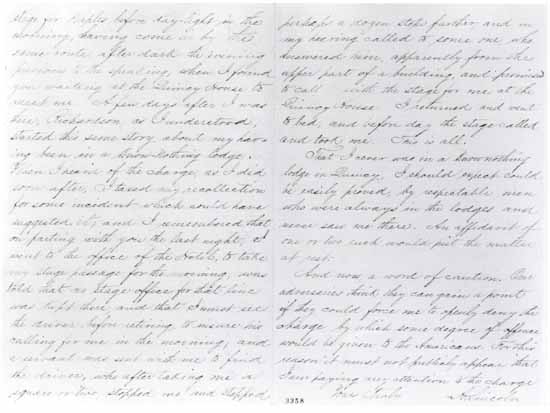

Yours of the 20th received. I suppose as good, or even better men than I may have been in American or Know-Nothing lodges; but in point of fact, I never was in one, at Quincy or elsewhere. I was never in Quincy but one day and two nights while Know-Nothing lodges were in existence, and you were with me that day and both those nights. I had never been there before in my life; and never afterwards, till the joint debate with Douglas in 1858. It was in 1854 when I spoke in some hall there, and after the speaking, you with others took me to an oyster saloon, passed an hour there, and you walked with me to, and parted with me at the Quincy House, quite late at night. I left by stage for Naples before day-light in the morning, having come in by the same route, after dark the evening previous to the speaking, when I found you waiting at the Quincy House to meet me ...

That I never was in a Knownothing lodge in Quincy, I should expect could be easily proved, by respectable men who were always in the lodges and never saw me there. An affidavit of one or two such would put the matter at rest.

And now, a word of caution. Our adversaries think they can gain a point if they could force me to openly deny the charge, by which some degree of offence would be given to the Americans. For this reason it must not publicly appear that I am paying any attention to the charge.

Yours Truly

A. LincolnWhatever was done, or not done, by Jonas, must have been effective because the matter was never mentioned publicly during the campaign.

|

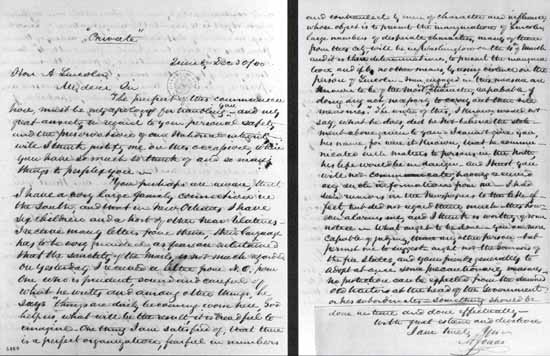

In a letter from Jonas to Lincoln on December 30, 1860, marked "Private," Jonas again alerts his friend:

The purport of this communication must be my apology for troubling you-and my great anxiety in regard to your personal safety and the preservation of our National integrity will I think justify me on this occasion, when you have so much to think of and so many things to perplex you.

You perhaps are aware, that I have a very large family connection in the South, and that in New Orleans I have six children and a host of other near relatives. I receive many letters from them, their language has to be very guarded, as fears are entertained that the sanctity of the mails, is not much regarded. on yesterday I received a letter from N.O. from one who is prudent, sound and careful of what he writes and among other things, he says "things are daily becoming worse here, God help us, what will be the result, it is dreadful to imagine. One thing I am satisfied of, that there is a perfect organization, fearful in numbers and contrauled by men of character and influence, whose object is to prevent the inauguration of Lincoln, large numbers of desperate characters, many of them from this city, will be in Washington on the 4th of March and it is their determination, to prevent the inauguration, and if by no other means, by using violence on the person of Lincoln. Men, engaged in this measure are known to be of the most violent character, capable of doing any act, necessary to carry out their vile measures." The writer of this, I know, would not say, what he does, did he not believe the statement above given to you. I cannot give you, his name, for were it known, that he communicated such matters to persons in the North, his life would be in danger — and I trust you will not communicate, having received any such information from me. I had seen rumors in the Newspapers to the like effect, but did not regard them much — this however alarms me, and I think is worthy of some notice. What ought to be done-you are more capable of judging, than any other person — but permit me to suggest — ought not the Governors of the free States, and your friends generally to adopt at once some precautionary measure-no protection can be expected from the damned old traitor at the head of the Government or his subordinates-something should be done in time and done effectually.

With great esteem and devotion

I am truly yrs —

A. Jonas

|

Jonas was one of the first to suggest Lincoln for the presidency. When Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Daily Tribune, went to Quincy for a lecture in December 1858, he met with a number of leading Republicans to discuss the election of 1860. Abraham Jonas and his law partner Henry Asbury were among them. Asbury later recalled that when the discussion turned to who might be a strong candidate, he proposed a likely one:

Mr. Greeley and one or two others asked who I meant. I said gentlemen I mean Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. I am sorry to say that my suggestion fell flat, it was not even discussed, none of them seemed for Lincoln ... Some one said Lincoln might do for Vice - President-at this point Mr. Jonas ... said: Gentlemen there may be more to Asbury's suggestion than any of us now think.

Dr. Isachar Zacharie, an English-born chiropodist, first met Lincoln in September 1862 on a professional call. A satisfied patient, Lincoln gave the doctor a testimonial, "Dr. Zacharie has operated on my feet with great success, and considerable addition to my comfort." Within a few months Zacharie was in New Orleans on a mission for the president. Two years later, the New York World wrote that the chiropodist and special emissary "enjoyed Mr. Lincoln's confidence perhaps more than any other private individual." Zacharie also involved himself in politics, actively soliciting the "Jewish vote" for the president. When honored by Jews in 1864, he expressed what may well have been his ambition as Lincoln's friend and confidant:

Let us look at England, France, Russia, Holland, aye, almost every nation in the world, and where do we find the Israelite? We find them taken into the confidence of Kings and Emperors. And in this republican and enlightened country, where we know not how soon it may fall to the lot of any man to be elevated to a high position by this government, why may it not fall to the lot of an Israelite as well as any other?

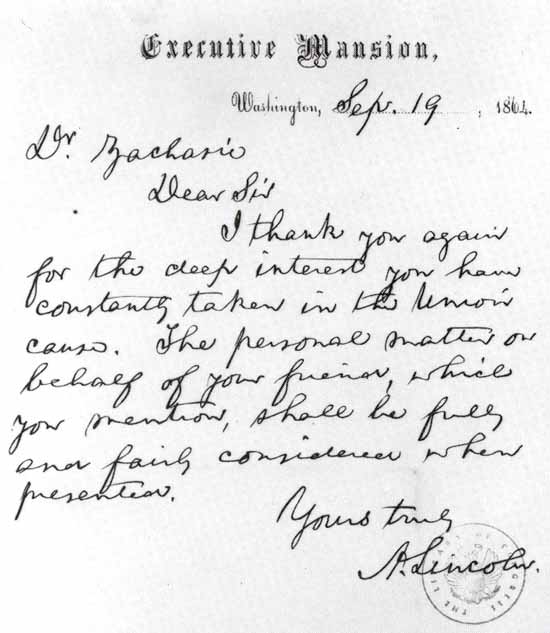

In the Lincoln Papers at the Library there are thirteen letters from Zacharie to Lincoln, and one dated September 19, 1864, apparently as yet unpublished, from Lincoln to Zacharie:

Dear Sir

I thank you again for the deep interest you have taken in the Union Cause. The personal matter on behalf of your friend which you mentioned shall be fully and fairly considered when presented.

Yours truly

A. LincolnTo which Zacharie replied:

Dear Friend,

Yours of the 19th came duly to hand, it has had the desired effect, with the friend of the Partie.

I leave tomorrow for the interior of Pennsylvania, may go as far as Ohio. One thing is to be done, and that is for you to impress on the minds of your friends for them not to be to [o] sure.

|

As rabbi of Congregation B'nai Jeshurun, the Rev. Dr. Morris J. Raphall (1798-1868), one of New York's more prominent clergymen, had gained renown as an orator, distinction as being the first rabbi to open the session of the House of Representatives with a prayer, and notoriety for his sermon The Bible View of Slavery, which was printed, reprinted, and widely distributed as a proslavery sermon by antiabolitionist forces. As Raphall told his congregation, when it assembled to mourn the martyred president, he knew Lincoln but slightly. He had met Lincoln only once, but on that single occasion the rabbi had asked a favor of the president and, as Raphall told his congregants, Lincoln had "granted it lovingly, because he knew the speaker to be a Jew-because he knew him to be a true servant of the Lord." The favor granted must have been the rabbi's request that his son be promoted from second lieutenant to first. Forty years later, in 1903, Adolphus S. Solomons of the book publishing firm of Philip and Solomons, in Washington, D. C., reminisced that he had helped Rabbi Raphall get an audience with the president, where that request was made and granted. Lincoln did even more for Raphall's son-in-law, Captain C. M. Levy.

|

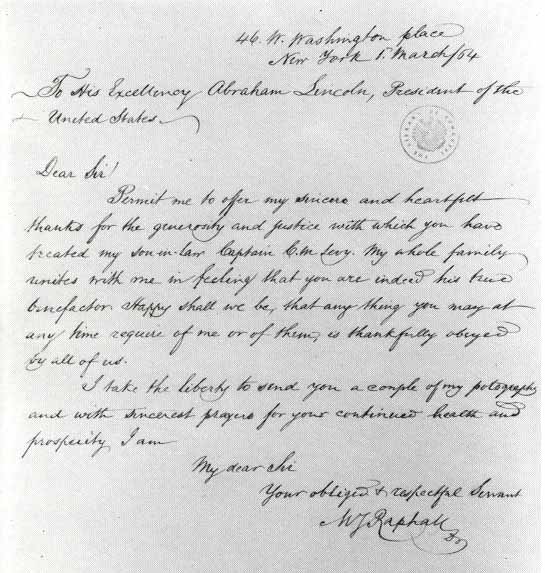

Assigned to the Quartermaster Department in Washington, Captain Levy undertook as an added task to distribute special food and clothing to Jewish soldiers in the capital's hospitals. On October 9, 1863, a Captain C. M. Levy was court-martialed and dismissed from service for unspecified charges. Apparently appealed to, Lincoln must have responded with his fabled compassion, for on March 1, 1864, Raphall wrote him thanking him "for the generosity and justice with which you have treated my son-in-law Captain C. M. Levy."

My whole family unites with me in feeling that you are indeed his true benefactor. Happy shall we be that any thing you may at any time require of me or them, is thankfully obeyed by all of us.

I take the liberty of sending you a couple of my potographs [sic] and with sincere prayers for your continued health and prosperity I am Your obliged and respectful servant, M. J. Raphall.

The "potographs" may well have been the prints of a photograph of the rabbi, first published by P. Haas in New York, 1850, of which the Library has a fine copy.

Sources:Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).