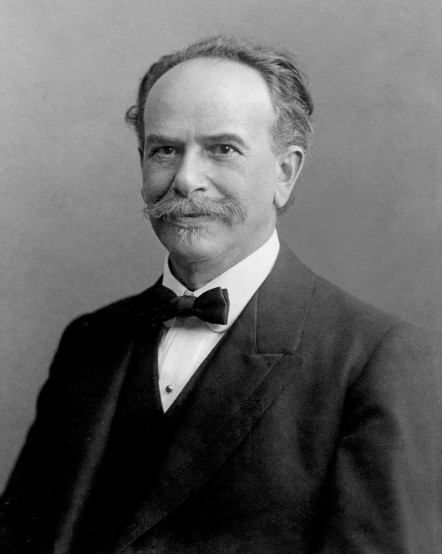

Franz Boas

(1858 - 1942)

Franz Boas, widely regarded as the “father of American anthropology,” was a German-born scholar whose pioneering work reshaped the study of culture and race in the 20th century.

Boas was born on July 9, 1858, in Minden, Westphalia, Prussia (today Germany), to a Jewish merchant family that embraced liberal ideals and the progressive values of the 1848 revolutions. As a child, he was frail in health, so he turned to books and the sciences, developing an interest in botany, geography, and astronomy. Although Jewish by background, he grew up identifying strongly with German culture.

He studied at the universities of Heidelberg, Bonn, and Kiel, earning a Ph.D. in physics with a minor in geography from Kiel in 1881. Following a year of military service, Boas pursued further studies in Berlin before joining a scientific expedition to Baffin Island in 1883–84. There, he observed the Inuit and gathered ethnographic data that shaped his future direction as a scholar of human cultures.

After returning to Germany, Boas worked at the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin and taught geography at the University of Berlin. His encounters with First Nations visitors to Berlin deepened his interest in Indigenous peoples of North America. In 1886, during travels in British Columbia, he stopped in New York City and chose to remain, joining the magazine Science as an assistant editor. That same year, he married Marie Krackowizer.

In the 1890s, Boas held teaching posts at Clark University and the University of Chicago before settling at Columbia University, where he became the first professor of anthropology in 1899. At Columbia, he established the first whole anthropology department in the United States. He also served as curator of ethnology at the American Museum of Natural History from 1896 to 1905.

Boas devoted decades to fieldwork among Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest, especially the Kwakiutl. He emphasized intensive field research and detailed cultural documentation, recording language, myths, and ceremonies with unprecedented precision. His insistence on studying cultures on their own terms laid the foundation for cultural relativism—the idea that no society is inherently superior to another.

In 1911, Boas published The Mind of Primitive Man, challenging prevailing racial hierarchies and arguing that environment and history, not biology, shaped cultural development. He later expanded these ideas in Race, Language, and Culture (1940). His research into immigrant populations also demonstrated the plasticity of human traits, undermining scientific racism.

Boas retired from Columbia in 1937 but continued writing and teaching as professor emeritus until he died in New York on December 22, 1942. Over his career, he authored hundreds of articles and books and trained a generation of influential anthropologists, including Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, Alfred Kroeber, and Edward Sapir.

Boas’s insistence on rigorous fieldwork, his rejection of racial determinism, and his advocacy of cultural relativism permanently altered the discipline of anthropology. Beyond academia, his writings against racism and nationalism influenced public debates in the early 20th century.

Sources: “Franz Boas”, Andrews University.

“Franz Boas”, Biography.com.

“Franz Boas”, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Charles King, “Genius at Work: How Franz Boas Created the Field of Cultural Anthropology,” Columbia Magazine, (2019).

Photo: Canadian Museum of History, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.