From the Land of the Czars: Dashed Hopes and Thwarted Expectations

Morris Rosenfeld (1862-1923) went to New York in 1886 and became a pioneer of Yiddish poetry in America. "Poet Laureate of Labor," he sang of sweatshop and tenement, exploitation and poverty, a threnody of dashed hopes and thwarted expectations. His poems became folk songs, and his own life mirrored the poverty and sadness of his songs.

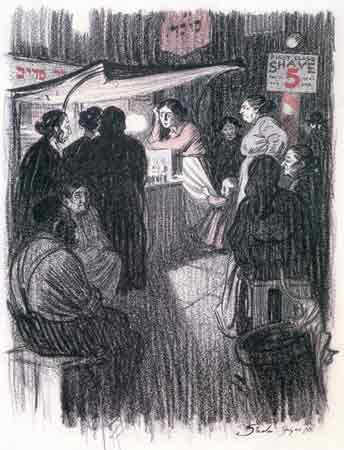

Ephraim Moses Lilien (1874-1925), an artist, illustrator, and printmaker, was the first artist to become an active Zionist. Lieder des Ghetto was one of his earliest important commissions, but the fullness of his talent is already evident. His drawings, done mainly in India ink, were a perfect medium for the somber themes of Rosenfeld's poetry.

Our two unfortunates had to leave, but as Rosenfeld saw it and Lilien depicted it, the plight of those permitted to remain was not much better: endless, unrewarding toil in the sweatshop. Illustrating "An der Namaschine" (At the Sewing Machine), a pious clothing operator, bearded and in skullcap, his tsitsith (holy fringes) dangling, sits at his machine. Man and machine have become one. Behind him, his bejeweled employer literally sucks his lifeblood. Rose Pastor Stokes and Helena Frank catch the essence and tone of this poem in their volume of translations, Songs of Labor by Morris Rosenfeld, Boston, 1914:

The Pale Operator

If but with my pen, I could draw him,

with terror you'd look in his face;

For he, since the first day I saw him,

Has sat there and sewed in his place.Years pass in procession unending,

And ever the pale one is seen,

As over his work he sits bending

And fights with the soul-less machine.More subtle and powerful is Lilien's drawing for "Die Thrane auf dem Eisen" (A Tear on the Pressing Iron), where a presser is bending over his work table, heavy pressing iron in hand. He is completely enclosed in a spider web, in which flies have been caught, and lurking in the top corner of it is a malevolent black spider. Wiener's prose translation reads:

Oh, cold and dark is the shop. I hold the iron, stand and press;-my heart is weak, I groan and cough. . My eye grows damp, a tear falls, it seethes and seethes, and will not dry up.

"Are you perhaps the messenger ... that other tears are coming? ... when will the great woe be ended?"

I should have asked more of ... the turbulent tear; but suddenly there began to flow more tears, tears without measure.

Long hours and drudgery were not limited to the sweatshop. The lot of the street peddlers was no better, and in foul weather, worse. Two original drawings by the illustrator William Allen Rogers, "The Fruit Vendor" and the "Candle Merchant," accompanying a brief sketch, "Friday Night in the Jewish Quarter," in Harper's Weekly, April 19, 1890, capture this perfectly. It is spring, but the vendor is dressed in winter hat, coat, and boots. Standing by his three-wheel pushcart, holding out two pieces of fruit in his right hand, he holds his left hand open in supplication, which matches the look on his wizened face.

|

To call the old woman selling candles a "merchant" is an act of compassion. The sad mute plea on a face wearied by the tribulations of life mark her a beggar as much as a vendor. Her clawlike fingers clutch her means of livelihood, a tray of Sabbath candles still unsold. One is reminded of one of Rosenfeld's most popular and lugubrious poems, "The Candle Seller" (translation by Stokes and Frank):

In Hester Street, hard by a telegraph post,

There sits a poor woman as wan as a ghost.

Her pale face is shrunk, like the face of the dead,

And yet you can tell that her cheeks once were red ...

"Two cents, my good woman, three candles will buy,

As bright as their flame be my star in the sky!" . . .She's there with her baby in wind and in rain,

In frost and in snow-fall, in weakness and pain....

She asks for no alms, the poor Jewess, but still,

Altho' she is wretched, forsaken and ill,

She cries Sabbath candles, to those that come nigh,

And all that she pleads is, that people will buy.But no one has listened, and no one has heard:

Her voice is so weak, that it fails at each word ....I pray you, how long will she sit there and cry ...

How long will it be, do you think, ere her breath

Gives out in the horrible struggle with Death?In Hester Street stands on the pavement of stone

A small, orphaned basket, forsaken, alone.

Beside it is sitting a corpse, cold and stark:

The seller of candles-will nobody mark?

No, none of the passers have noted her yet ...Rogers also illustrated Sylvester Baxter's "Boston at the Century's End," in Harper's Magazine, November 1899, and among those illustrations is "The Jewish Quarter of Boston," of which the Library has the original. Mary Antin describes the "Quarter" in her The Promised Land.

|

Anybody who knows Boston knows that the West and North Ends are the wrong ends of the city. They form the tenement district, or, in the newer phrase, the slums of Boston ... [it] is the quarter where poor immigrants foregather, to live, for the most part, as unkempt, half-washed, toiling unaspiring foreigners; pitiful in the eyes of social missionaries, the despair of boards of health, the hope of ward politicians, the touchstone of American democracy.

William Allen Rogers's original drawing of "The Jewish Quarter of Boston," for Sylvester Baxter's article, "Boston at Century's End," which appeared in Harper's Magazine, November 1899.

Prints and Photographs Division.

On the other side of the coin is the tale of a Jewish immigrant girl, Yetta, the appealing sprite in Frederic Dorr Steele's original drawing to illustrate Myra Kelly's, "A Passport to Paradise," in McClure's, November 1904. Yetta is the heroine in one of Miss Kelly's touching tales about Jewish children of the Lower East Side. Born in Ireland, Myra Kelly lived most of her brief life-she died at thirty-five--in that section of New York, where she taught public school. Her stories appeared in leading magazines and were subsequently published in three collections. Theodore Roosevelt expressed the appreciation of many:

Mrs. Roosevelt and I and most of the children know your very amusing and very pathetic accounts of East Side school children almost by heart, and I ... thank you for them. While I was Police Commissioner I quite often went to the Houston Street public school and was immensely ... impressed by what I saw there. I thought there were a good many Miss Bailies [the schoolteacher heroine of Miss Kelly's stories] there, and the work they were doing among their scholars (who were so largely of Russian-Jewish parentage, like the children you write of) was very much like what your Miss Bailey has done.

|

"A Passport to Paradise" is a bittersweet story of a little immigrant girl with a penchant for cleanliness, hard to achieve when water had to be brought up to the tenement apartment from the yard below; an ambition to serve in the exalted position of monitor; and a longing for her country peddler father whom she sets out to find, arousing fears that she has become lost. Most of all it is a loving account of Jewish boys and girls and their relationship with their Irish teacher. Steele's drawing catches the pathos and wonder of the immigrant community in the Jewish neighborhoods of tum-of-the century American cities, where there was a natural community bound together by memory, empathy, and shared aspirations.

|

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).