Klaus Barbie

(May 1987)

On May 11, 1987, after four years of legal wrangling, Klaus Barbie, the SS officer in charge of the Gestapo in Lyon, France from November,

1942 to August, 1944, would finally attend his long overdue meeting

with justice. There was little doubt that Klaus

Barbie, a frail old man sitting in the defendant's box of a French

courtroom, was the same Klaus

Barbie who had been responsible for thousands of deaths forty years

earlier. Of Barbie's hundreds of crimes, including murder, torture,

rape, and deportation, only those of the gravest nature, the "crimes

against humanity," would be pursued at the trial. Specifically,

Barbie would be tried for his role as a perpetrator of Hitler's Final Solution and the material

evidence against him was staggering.

|

When the trial began, the forty-lawyer prosecution

team, which represented Klaus

Barbie's myriad victims, opened its argument by reciting a list

of Barbie's crimes. The list turned out to be so long that the entire

first day of the trial was devoted to its reading. Moreover, the prosecution

had scores of witnesses, mainly those who had been tortured by Barbie

because he suspected that they were members of the French Resistance

or because they were Jewish.

While the prosecution was preparing its witnesses,

the defense was preparing its own argument. To defend Barbie, who France already sentenced to death twice, in absentia, would be a daunting and

unpopular task, but for a radical lawyer named Jacques Vergès,

the Barbie trial was the moment for which he had spent most his entire

adult life preparing. Vergès' defensive strategy was in his own

words to "attack the prosecution," and almost as soon as the

judges let him speak, he transformed Barbie's trial into a trial of France and of something much

greater, history itself.

- Historical Background

- The Occupation: The Years France Forgot

- Criminal In Absentia (1945-1983)

- Preparing Barbie's Defense (1983-1987)

- The Courtroom (1987)

- Conclusion

Historical Background

On April 6, 1944, actually Maundy Thursday, three vehicles,

two of which were lorries, pulled up in front of the children's refuge

in Izieu, a sleepy village nestled in the piedmont east of Lyon. The

children, most of whom were Jewish, were hiding in Izieu in order to

escape their hunter, the regional Gestapo,

which was led by First Lieutenant Klaus

Barbie. The lorries' arrival signaled the end of this hunt and as

a witness later recalled, Barbie's Gestapo caught its quarry:

It was breakfast time. The children were in the

refectory drinking hot chocolate. I was on my way down the stairs

when I saw three trucks in the drive. My sister shouted to me: it's

the Germans, save yourself! I jumped out the window. I hid myself

in a bush in the garden...I heard the cries of the children that were

being kidnapped and I heard the shouts of the Nazis who were carrying

them away...They threw the children into the trucks like they were

sacks of potatoes. Most of them were crying, terrorized.1

Following the raid on their home in Izieu, the children

were shipped directly to the "collection center" in Drancy

by the Gestapo. Upon reaching

Drancy, the children were put on the first available train "towards

the East" and, of the forty-four children kidnapped by the Nazis

in Izieu, not a single one returned.2 The

most tragic aspect of the Izieu raid, however, was that Barbie would

have never found the children had patriotic French citizens not volunteered

to help him search for refugees.

When Klaus

Barbie arrived in Lyon in November, 1942 he was assigned two tasks,

to dismantle the Resistance and rid the city of Jews.3 The city's medieval architecture had earned Lyon the title of "Capital

of the Resistance" by providing more than enough cul-de-sacs and

long-forgotten basements in which guerrillas and refugees could hide.4 Barbie's job, however, was not nearly as difficult as it sounded. For

every résistant he encountered, Barbie found that there were

equal numbers of French willing to collaborate with him. Many of the

French who collaborated with Barbie did so out of greed or a lust for

power, but many more collaborated simply because they believed what

they doing was good for France.

The reason for this, as Barbie would soon discover, was that two completely

different notions of what it meant to be French existed side by side.

Such coexistence often led to violence, but more importantly, it both

fed upon and nourished French society's disregard for certain elements

of its past. Barbie's role in that nation-scale oversight was key; during

the Occupation, he manipulated and reinforced it, and during his trial

in 1987, he provided the means to destroy it. Destroying national amnesia,

however, is no easy task considering how far into the past it reached.

The story of the Barbie trial begins not during World

War Two, but with the Enlightenment, where the ideas that propelled

both Barbie and those who judged him were born. Philip Potter, a pastor

from the Antilles, knew as much when he was interviewed by Le Monde

shortly after Barbie's extradition to France:

In reality, Barbie and his like are the products

of your [French] history. Hitler,

Barbie, Eichmann, and

company represent the end of the Aufklärung (century of Enlightenment)

which produced four things: the Industrial Revolution, which subordinated

man to the machine; the founding of the United States on a declaration

of independence where liberty and equality were applied to all men

-- except for blacks and Indians; the French Revolution of 1789 where

liberty, brotherhood, and equality were indeed claimed by the bourgeoisie;

and imperialism based on racism.5

It was the Enlightenment that proclaimed all men to

be equal and that all equals be treated as equals; it was also the Enlightenment

that allowed people to look at the world from a more rational, scientific

perspective. Although this way of thinking transformed France into one of the world's greatest democracies, it also made France into a breeding ground for a new, extremely dangerous form of racism.

Thus, it was the Enlightenment's dual nature that allowed France to become the first nation to grant full civil rights to all of its

minorities and concurrently become the first nation in which racism

was justified through scientific reasoning. As was demonstrated in the

rise of guillotine following the French Revolution, all it took was

a tweak here and a twist there to employ the newfound knowledge to making

blood both boil and flow.

As liberty and equality became rationalized, so did

hatred. It was this dual nature that brought suffering to those who

benefited most from the principles of the Enlightenment when those same

principles were distorted. No finer example exists of the Enlightenment's

dual nature than the fate of the European Jews. When France,

in a fervor of putting the principles of the Enlightenment to good use,

became the first nation to grant full rights to all of its minorities,

including Jews, it also provided fertile soil for hatred to take seed

and grow. As the Jews used their newfound civil rights to integrate

into French society, they increasingly became the victims of a new form

of racism, a scientific one. While democracy and equality were being

rationalized, so were nationalism, xenophobia, and racism. Consequently,

by the 1880s, those who continued to be anti-Semitic,

despite the lack of a religious basis for doing so in a secular democracy,

now had a whole new set of ideas on which to base their hatred.

Now, instead of being persecuted for religious reasons,

Jews became the victims of economic and then racial discrimination.

French Jews, who were well-integrated into French society by the 1880s,

were disproportionately involved in the nation's finance and capital

markets. Whenever there was an economic downturn, the Jews got blamed,

and, this being the age of scientific reasoning, anti-Semites began

looking for scientific explanations for the Jews' place in society.

If there was a "French national character" then there was

also a "Jewish character," and the new generation of French

anti-Semites viewed the two as conflicting.6 Theories emerged that Europe was dominated by Jews, who through their

heavy involvement in finance, academics, and culture managed to control

a disproportionate share of power and wealth. The Jewish "character"

was blamed by many rightist thinkers for the rise of socialism and the

collapse of Europe's monarchies. Everywhere the European Right saw their

enemies they also saw Jews. It was Karl

Marx, a Jew, who designed communism, and it was therefore the Jews

who were destroying Europe's status quo. If Marx was Jewish, then so

was communism, and as the Right intensified its battle against Marx's

growing popularity, it stepped up its battle against the Jews as well.

The new racial anti-Semitism was

therefore neither a spontaneous nor an isolated event, and it often

went hand-in-hand with nationalism, xenophobia, religiosity, and monarchism.

Furthermore, the new wave of anti-Semitic nationalism would prove itself as only the tip of the iceberg of a much

larger trend, one which earned Paris the title of "the spiritual

capital of the European Right."7

The turn-of-the-century marked a new age for French

tolerance and a new age for French anti-Semitism as well. Religious tolerance was on the rise and by the 1890s, Jews

were even allowed to serve as officers in the French Army, traditionally

a bastion of conservatism and therefore anti-Semitism.

The first modern test of the Jewish presence in France began in 1895 when Alfred

Dreyfus, the first Jew to serve as an officer in the French Army's

General Staff, was stripped of his medals and denounced as a traitor

and a spy. From this incident, which soon swelled into a decade-long

national drama, French anti-Semitism got a major boost. Many French already distrusted Jews and the Dreyfus

Affair gave them the perfect opportunity to continue doing so. In

the minds of many French nationalists, especially the militarists on

the monarchist Right, Dreyfus was a spy and a traitor because he was

greedy and hated the French. Why would he be greedy and hate the French?

Because he was a Jew. And why would a Jew be greedy and hate the French?

Because that was his character, his essence, his inner-being, his Jewishness.

Rightists like Charles Maurras, the founder of Action

Française, typified those who used the Dreyfus

Affair to gain support for their attacks on the Jewish presence

in France. As Erna Paris put

it, "Maurras was no mass murderer, to be sure, but rather an aesthete,

a snob, a worshiper of the ancient world, a masculinist...and an elitist

in every sense of the word."8 By 1889,

La Libre Parole, the daily paper of Action Française whose sole

purpose was to attack the Third Republic, boasted a circulation of about

300,000.9 Every time something went wrong

on any level, papers like La Libre Parole blamed the policies of the

Third Republic for whatever happened. Specifically, La Libre Parole

attacked the Third Republic for its liberalness and its toleration of

foreigners, especially Jews. Moreover, these papers frequently revealed

Jews at the center of the Third Republic's scandals and occasionally

even called on the government to revoke the citizenship of Jews or at

least put some restrictions on their involvement in French government,

industry, and culture. Thus, when Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew, was denounced as a traitor, men like Maurras

were ready to pounce. Even though Dreyfus was eventually pardoned, the

uproar surrounding his trial and incarceration renewed the public's

traditional fear of France's

Jewish population, and groups like Action Française were allowed

to ease xenophobia into popular acceptance.

Along with their newfound popular acceptance, French

anti-Semites found that their political base was expanding as well.

During the Dreyfus trials, the anti-Semites held a great deal in common

with conservatives and military leaders whose interests would be advanced

by condemning Dreyfus. Both groups wanted to change or remove the Third

Republic and both groups saw multi-culturalism as a threat to French

society. In both groups, most members were ardent nationalists like

Maurras, some were devout Catholics, and many were enemies of the Republic

as well. They saw the Third Republic as a great hindrance to France for among other reasons, its tolerance of minorities and liberals. Armed

with their new theories of French racial character, they were alarmed

by the Third Republic's willingness to taint French culture by allowing

outsiders to settle there. As a result of the popularity of groups like

Action Française and their association with the popular Right,

many French began to believe that they could not be good nationalists

without being at least mildly anti-Semitic.

Although groups like Action Française appealed

to many by attaching anti-Semitism and xenophobia to the promise of a better future for France,

they were not without opposition. While the French anti-Semites used

the Dreyfus Affair popularize their cause, an equally vocal group defended Dreyfus, and

indeed the whole Jewish presence in France,

against false accusations made against them. When it became clear that

Dreyfus had been framed, the journalist Emile Zola wrote his famous

article entitled "J'Accuse" in which he pointed out the inconsistencies

of Dreyfus's enemies, most of whom were both conservative and anti-Semitic.

For the Left as well as for the large non-socialist Republican Center,

a conviction of Dreyfus would go against tolerance and justice, two

values held dear by the Third Republic. Thus, by the time the Dreyfus

Affair ended, France was

completely polarized over the issue of Dreyfus's role in the army and

over the larger issues of the Jewish presence in France and the validity of what the Third Republic stood for. For the most

part, the socialists and the Center supported Dreyfus while most conservatives,

monarchists, and the military opposed him. Both sides refused the change

their views, but for the time being the more liberal values of the Republic

prevailed and the Right was forced to confine its anti-Semitism to a more tacit level. Although anti-Republicanism and the anti-Semitism went with it were buried, they certainly had not died.

Much of the xenophobia and anti-Semitism that was aroused during the turn of the century disappeared from the

political arena during World War I. On the battlefields of Verdun, the

Somme, and Ypres, French Christians and Jews fought and died side by

side for France. Those who managed

to survive the ordeal of the trenches were respected regardless of their

creed or ancestry. Henceforth, all one had to do to refute the arguments

of an anti-Semite was simply to point to one of France's

many Jewish veterans. Consequently, anti-Semitism in France declined during the

1920s, and as the decade progressed, it faded from most aspects of life

with the notable exceptions of social clubs and spousal choice.10 Moreover, French Jews were allowed to integrate more than ever and it

would be fair to say that France during the 1920s was much more tolerant of Jews than the either the

U.S. or the U.K. at the time.11

France's national

mood of unity and toleration that followed the war was doomed for precisely

the same reasons it came about in the first place. The 1920s attitude

of toleration and unity hinged on a rebounding French economy and a

stable society. As long as mouths were fed, pockets were full, and jobs

were available, everybody was fairly happy, but this national mood of

content quickly faded when France succumbed to the Great Depression in the early 1930s. Besides bringing

mass unemployment and therefore mass unrest to France,

the Great Depression brought Adolf Hitler to power in Germany. France not only had to worry about its internal upheaval, but it had to face

the growing threat of yet another war with Germany as well. After World War One, the French were simply tired of war, especially

given their atrocious losses and the fact that much of that war was

fought on French soil. In the trenches on the Western Front, France lost a whole generation of young men and like most other nations that

participated in the slaughter, France had no desire to repeat the experience ever again. Understandably, France's

foreign policy reflected the popular pacifism brought about by World

War One, and almost all French, from Communists to right-wing radicals,

despised the idea of another war.

Such pacifism on the part of French society beckoned

like a siren's wail to Adolf Hitler,

who from the start of his political career declared that the "mongrel"

French stood firmly in the path of German progress.12 As one of primary forces behind the massive burdens heaped upon Germany at the conclusion of World War One and as a society unprepared for war, France provided an ideal target

for the expansionist Nazis. To make matters worse, French pride in the

Republic bitterly opposed fascism, with which Hitler had replaced the Weimar Republic. Nazi "philosophers" hurled

invectives against the principles of the Enlightenment, which they viewed

as responsible for the rise of the Republic and the Jews. Ironically,

the Nazis owed their ideology of the Volksgemeinschaft, the organic

people's state, to the same principles of the Enlightenment that paved

the way for the French Republics and their toleration of religious diversity.13 Just as French anti-Semites derived their science-based views from the

Enlightenment, the Nazis drew their own brand of anti-Semitism from the same scientific principles.

As if a faltering economy and a looming war were not

enough, France was flooded by

a steady stream of refugees fleeing fascism and poverty. Most prominent,

although not most numerous, were the Jewish refugees from the east.

From Poland and other places

in eastern Europe came a wave

of poor, uneducated, and very unassimilated Jews. When these eastern

Jews arrived in cosmopolitan France they spoke little or no French and placed a great strain on the French

economy that was already facing record unemployment. Not only did these

Jewish immigrants clash with French culture, they, like all immigrants,

were viewed as threats to French job security. Thus, from fears of job

displacement arose yet another kind of anti-Semitism,

one in which Jews were, depicted as "predatory proletariats."14 When anger towards Jewish immigrants expressed itself in renewed hostility,

fully assimilated and highly successful French Jews were often lumped

together with their poor immigrant counterparts. As a result, economic

worries became blended with traditional anti-Semitism,

and the word "Jew" began to mean "job stealer" as

well as "exploiter."

Although French xenophobia was on the rise in the early

1930s because of the socioeconomic problems brought about by the new

wave of poor immigrants, the bulk of the French population was sufficiently

liberal and open-minded to elect in 1936 the Popular Front headed by Léon Blum, a socialist and

a Jew. The Popular Front's main platform stood against the fascism that

was on the rise in France's neighbors Germany, Italy, and Spain. Although

the Popular Front had put a Jew in power, the same forces that persecuted

Dreyfus were also returning. For the enemies of the Third Republic,

many of whom were anti-Semitic,

or became anti-Semitic once Blum

took office, Blum's role as Premier confirmed their fears that Jews

were taking over France. They

pointed to France's sluggish

economy and deteriorating relationships with its fascist neighbors as

sure signs that the Jews were out to ruin France.

Many also feared that an enraged Blum and his "Talmudic Cabinet"

would try to pick a fight with Germany because of Hitler's anti-Semitism.15 In reality, Blum's administration made great efforts to appease Hitler,

and ironically, that effort to make peace would soon bring unprecedented

disaster to France.

When something went wrong in France during the Blum administration, and a lot did go wrong in the late Thirties,

the Jews as a group were often blamed along with Blum's government and

the immigrants. To make matters even worse for Blum, France experienced the Refugee Crisis, its biggest-ever surge of refugees,

between 1938 and 1941. When Germany began to expel political opponents and Jews en masse in 1938, many of

them ended up in France, and

soon other waves of political refugees swept in from fascist Spain and

Italy. As if the sheer volume of refugees was not enough to test French

tolerance of outsiders, many of the refugees were violent political

extremists, not the type of people a society on the verge of turmoil

wanted. Although the French tried to prevent the refugees from ending

up in France, they had the misfortune

of sharing the same landmass with the source of the refugees. From the

Blum administration's point of view, France was faced with the choice of paying for the refugees' food, clothing,

and shelter or letting them run amok in the streets. Either way, Blum

would lose.

In the southern regions of France,

massive camps de concentration were set up for the destitute refugees.

The bill came to $6 million per month to run each of these camps and

Blum got blamed for the whole thing.16 In the area where the camps were located, later to become the geographic

heart of the Vichy regime, the locals had become thoroughly fed up with

refugee situation. Henceforth, the cards were stacked against the refugees

from the minute they entered France.

Immigrants could not find work because there were no jobs, they could

not integrate because they were unwanted, and they could not leave because

they were trapped. Worse, to many native French, the refugees seemed

like a lost cause. As evidence, they pointed out that the refugees,

many of whom were Jews, were not working, were not assimilating, and

were staying on French soil completely at France's

expense. In short, the locals wanted the refugees out, immediately.

They would have their wish granted much sooner than they expected.

Unfortunately for Blum, the situation went from bad

to worse as the surge of refugees swelled due to the deteriorating situations

in their homelands. After a decade of economic regression and social

upheaval, the traditional Republican tolerance of refugees was pushed

beyond its limit. As popular sentiment against the Jews intensified

because of the Refugee Crisis and the apparent ineptness of Blum's government,

the distinction between assimilated French Jew and immigrant faded while

the old distinction between Catholic Frenchman and Jew resurfaced. Many

conservative and pacifistic French began to worry that the Refugee Crisis

would drag France into war with

her fascist neighbors and they often blamed the Jews for the growing

tensions in Europe. The idea that it would be the Jews who dragged France into war was reinforced in 1938 when Herschel Grynszpan, a recent Jewish

immigrant to France, shot and

killed a German diplomat in Paris.17 In

the minds of conservative pacifists, the Grynszpan incident was a worst-case

scenario: a Jew, who was an unwelcome burden for France to begin with, had sabotaged the already delicate relationship between France and Germany.

When war between France and Germany finally broke out

on September 3, 1939, it was certainly not because Blum had picked a

fight with the Germans. Instead, it was Hitler's

aggression and the Nazis' fear that France would become a formidable foe if given enough time to build up its armies

that prompted the Werhmacht to sweep across the Low Countries into France.18 Before the German army even reached French soil, however, France was invaded by over a million refugees from Holland and Belgium who

were fleeing the advancing armies. The wave of panic-stricken mobs that

poured into France made the Refugee

Crisis of the late Thirties seem like a picnic. For the French government,

which was trying to fight a war at the time, this flood of refugees

could not have come at a worse moment. Desperate times called for desperate

measures and the government resorted to cramming thousands of refugees

in boxcars and shipping them to the already crowded camps de concentration.

The camps de concentration were nothing like the camps the Nazis would

soon run, but conditions there were nevertheless wretched; a typical

camp de concentration being the Velodrome d'Hiver, a huge indoor sports

complex in Paris where up to 5,000 refugees lived in squalor for months.

In the camps, families were split apart and disease ran rampant. Most

refugees, however, did not end up in the government-run camps and when

the hotels and boarding-houses filled up or when they ran out of money,

they simply lived on the streets.19 In

every public space in Paris there were refugees and where there were

refugees there was chaos.

Many French citizens were so angry about refugee situation

that they demanded an armistice with Germany just so that the refugees could be sent home. If the war between France and Germany would end, then

so would the refugee problem. Those who wanted a quick end to the war

got their wish as the combination of German innovation and French ineptness

on the battlefield, caused mainly by poor leadership and outdated tactics,

brought the "Phony War" to an end a scant two months after

the Germans began their westward push. With the German troops on their

way to Paris and with the French armies nowhere to be seen, there was

absolutely nothing to stop Nazi Germany's

occupation of its longtime enemy, France.

In the chaos following the German invasion of May-June

1940, the Third Republic collapsed. The death knell of the Third Republic

occurred on June 14, 1940 when the Germans entered Paris. Two days later,

with a swastika hanging from the Arc de Triomphe and German soldiers

goose-stepping down the Champs-Elysees, the last remnants of the Third

Republic collapsed. That day, in a last-ditch attempt to salvage traditional

honor, the government gave full executive power to Marshal Philippe

Pétain. What Pétain was supposed to do was be a savior.

If Pétain could be a savior on the battlefields of Verdun where

he overcame terrible odds to halt the German advance in 1916, then he

could do it again in 1940. Pétain was no ordinary military leader

though, he attained the status of a demigod: "On the army's most

glorious day, Philippe Pétain had been its most glorious leader

and in the minds of those for whom the army was the nation, the Marshal

had become the incarnation of France itself."20

For rightist anti-Semites like Charles Maurras, Pétain's

ascension was a dream come true. Upon taking office, Pétain vowed

to "take up a righteous sword against liberalism, communism, and

'selfish capitalism' and rid our country from the most menacing threat

of all, that of money."21 France,

under Pétain's nominal leadership and under the guidance of conservative

nationalism would at once be proud, militant, and xenophobic. Thus,

when Maurras boasted that he would prefer a German occupier to the Third

Republic, he was deadly serious: "Our worst defeat has had the

good result of ridding us of democracy." 22 Within a week of its formation, Pétain's rightist government

settled in the resort town of Vichy and began to prepare a formal surrender

to German. The Vichy government's surrender to the German's would not

be a loss but rather a triumph, especially to those who disliked the

Third Republic so much. In its quest to battle the evils of communism,

a force that many, if not most, of Vichy's leaders saw as France's

true nemesis, Vichy found itself allied with the Nazis for more than

just reasons of survival.

Although those who ran the Vichy regime would later

claim that Vichy served to shield the French from the full wrath of

the Nazis, most of them had far more in mind than deterring the Nazis

when they first took charge.23 The leaders

of Vichy, who had been enemies of the Republic before it fell, had always

had their own visions for France and sought to implement them now that the Republic was gone. Who were

these men who led Vichy? One trait they had in common besides hatred

for the Third Republic was a strong sense of conservative nationalism.

Common aspects of the sort of nationalism found in Vichy's leaders were

xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and anti-Leftism.

They were the old Right who fought against Dreyfus forty years before

and they were the old Right who had been denied any political say for

decades.

Though one would think that people who were so ardently

nationalistic would be the first the resist the invading Germans, in

fact the opposite was true. Even though many of these nationalists were

fiercely anti-German, their drive to purge France of what they called "subversive elements" overpowered their

hostility towards the invaders.24 The Germans,

after all, were fighting against the Communists and the Jews, two groups

that rightist French nationalists traditionally hated. Consequently,

more than a few Pétainists saw the German invasion as a blessing

because it would for the first time give them a free hand in ruling France and in fighting their

traditional enemies, the Communists and the Jews. Some French were so

impressed by the Nazi zeal against Bolshevism that they volunteered

to serve in the Waffen ("fighting") SS.

The 20,000 Frenchmen who fought in the "Charlemagne" division

of the SS fought so well

that several were awarded the Iron Cross for their actions on the Eastern

Front.25 By keeping in mind the extremely

nationalistic beliefs of men like Maurras one can understand that they

were not collaborating with the Nazis because they admired Germans but

because collaboration would be best way to obtain their vision of a

"pure" France. Pierre

Laval, the man who really ran the Vichy regime, was sure that the Germans

would eventually conquer all of Europe and wanted to ensure that France would still be a major power when the Nazis prevailed.26 He sought to accomplish this by playing a dangerous game of diplomacy

during which he tried to wheedle concessions out of the Germans in exchange

for French cooperation.

Many times the interests of the Vichy regime and of

the Nazis coincided. When the Nazis demanded that Vichy France deport its Jews, the Vichy government wholeheartedly complied. The Rightist

xenophobes who ran Vichy were overjoyed that the Germans wanted to take

the refugees off their hands and ordered the milice, state-sponsored

militia units that did the dirty work for the Vichy government and ultimately

the Nazis, to begin rounding up the Jews. Probably no two Vichy leaders

had the same reason for supporting the deportation of the Jews, though.

Populist leaders answered to the many inhabitants of southern France who wanted the foreign Jews deported because they were fed up with the

refugees and the camps de concentration. Besides the popular backlash

against the refugee camps, ultra-conservatives associated the Jews with

communism and saw the deportations as a sign of the true France reasserting itself. Meanwhile, racial anti-Semites like Maurras who

saw the Jews as a threat to French culture shed no tears when they were

"excised."27

The incarnation of the Vichy regime's nationalistic

ideology took the form of the Alibert law, which was perhaps the most

blatant expression of anti-Semitism in France during the Occupation.

The Alibert Law isolated and alienated Jews by excluding them from all

state administration jobs, and forbade them to work in the press, cinema,

radio, and theater. This law was applied mercilessly to all Jews, assimilated

and non-assimilated, with the exception of war veterans. Though it is

tempting to claim that the Vichy government passed such laws to appease

their Nazi masters, those who drafted and enforced Vichy's anti-Semitic policies asserted that such laws had nothing to do with Nazism. Xavier

Vallat, Vichy's Commissioner-General for Jewish Affairs proudly claimed

from his prison cell that Pétain's government was not a "servile

plagiarist of the Nazis" and that the anti-Jewish legislation of

Vichy never went beyond the "just limits set by the Church in order

to protect the national community."28 Revealingly, Vallat boasted that "The Alibert Law...owes nothing

at all to Nazism," and dispelling any doubt about the origins of

the Alibert Law, continued: "...M. Raphael Alibert was only adhering

to a policy which found not only its source in a long national tradition,

but also its justification in the position taken throughout the centuries

by the Church with regard to the Jewish problem." 29

When Vallat claimed Vichy's anti-Semitism was a product of French tradition rather than Nazi occupation, he also

went to great lengths to defend Vichy's anti-Semitism by pointing out the differences between it and Nazism. Vallat thus argued

that the surfacing of French anti-Semitism during Vichy was part of the popular French Catholic tradition and not

something forced upon the French by the Nazis. In defense of his claim,

Vallat points out the similarities between Vichy's anti-Semitism and that of the various popes throughout the ages. Following this logic,

even the Vichy decree of forcing Jews to wear yellow

stars did not come from the Nazis but rather from Pope Honorius

III who introduced the idea in 1221.30 Such a distinction is echoed by historian Eric Hobsbawm who claims the

Holocaust arose from the same "grassroots" anti-Semitism of eastern Europe that catalyzed

pogroms as opposed to the more academic anti-Semitism of Western Europe.31 Furthermore, the Vichy

government did not force Jews to live in ghettos or force them out of

public areas. Nor did it forbid mixed marriages or social interaction

between Jews and gentiles.32 Vichy's anti-Semitism,

concluded Vallat, was even milder than the what papal legislation called

for and therefore much milder than Nazi legislation.

Vallat's mentality is perhaps best illustrated in his

attitude toward to the Nazi plan to exterminate the Jews. In his memoirs,

Vallat also says that he knew of the Final

Solution starting in January, 1941, but that he "had problems"

with the Nazi plans.33 His main concern

at that time was to protect the French "national community,"

and he therefore wanted to rid France of all foreign Jews, regardless of their fate. Thus, Vallat was quite

relieved when the Germans began to deport foreign Jews in large numbers

as well as French Jews who "threatened the national community."

But as much as Vichy wanted to get rid of the Jews, it also wanted political

leverage with the Germans and Laval unhesitatingly used trainloads of

Jews as his bargaining chips. When the Germans did not grant Vichy the

concessions it demanded in exchange for a given number of Jews or French

laborers, or material goods, Laval would withhold all exportation of

humans and materials until the Germans complied. Until his execution

as traitor in 1945, Laval firmly believed that his collaboration with

the Nazis was a patriotic act and he died shouting "Viva La France!"34 Those who shot him believed the opposite, that they were serving France's

best interests by ridding it of collaborators like Laval. It is this

duality that allowed the two sides of France to coexist during the Occupation (the subject of the next chapter) and

it is this duality that determined the course of Klaus

Barbie's trial forty years later.

The Occupation: The Years

France Forgot (1940-1945)

When the Germans invaded France,

they only occupied the portions of France that provided them with what they thought would be worth the expense

and trouble of occupation. The Germans therefore occupied Paris, the

Channel Coast, and the Atlantic Coast. Paris was important because it

was a capital and controlling it meant controlling the region. The North

and West coasts were the front between the Germans and their main enemy

at the time, the British. By being located between territory that the

Germans firmly controlled and Mussolini's Italy, the southeastern part

of France was strategically negligible

and thus not worth the trouble of occupying. Not wanting to waste their

valuable resources guarding a secure region, the Germans left southern France complete in French hands.

The Germans also had bigger plans than just occupying France.

In 1940, Hitler was

pooling every available resource the Reich had for his main attack,

the one against his ideological enemy but then ally, the Soviet Union.

If the French wanted to govern themselves and cooperate too, then why

should the Germans waste any of their precious resources that they could

be using in their fight to gain Lebensraum in the East.

Although the Vichy regime's zeal for persecuting the

Jews pleased the Nazis a great deal, it alienated and angered the bulk

of the French population. While some Frenchmen were glad to see the

foreign refugees get sent back East, many were horrified when Vichy

began to deport French Jews. When Frenchmen saw other Frenchmen handing

their compatriots over to the Nazis, they became disillusioned then

infuriated. For many, the mistreatment of the Jews was the key factor

that caused them to join the Resistance but resistance did not always

take the form of fighting. While some French blew up railroad tracks

or shot Nazis, many men and women resisted Vichy and the Nazis passively

by refusing to collaborate or by hiding rèsistants and Jews.

Perhaps the best illustration of France's

dual nature can be found in the film, Au Revoir Les Enfants. In the

film, which is based on a true story, a group of priests hide French-Jewish

children in their boarding school, but their generosity ends in tragedy

when someone on their own staff informs the Gestapo of their crime. When the Gestapo arrive to haul the Jewish children and the head priest off to their

certain deaths, the informant, a young Frenchmen, seems quite proud

of his work.

By 1942, the Vichy government was in full-swing and

at the peak of its power. Under Vichy, order had been restored, the

refugee problem solved (many of them were deported, never to be heard

from again) and it looked as if France might be entering a special relationship with her patron and ally, Nazi Germany. In Germany,

1942 was also the year it achieved its greatest power. On January 20,

1942, the Nazis held the Wanasee Conference and worked out all of the

details of the Final Solution and decided to put it into action. By choosing to exterminate the Jews,

the Nazis had opened their war on three fronts; Russia, Western Europe,

and Jewish civilians. In 1942, the Third Reich was at its maximum size:

its territories stretched from the Urals in Russia to the Atlas mountains

of Morocco, and its enemies either lay in ruins or had yet to assemble

their armies. In 1942, it was also clear that Germany would not win its war nearly as quickly as everybody thought it would

in 1940. Defying what both Hitler and Pétain called its fate, Britain stubbornly held out against

German aerial attacks and was even beginning to strike back on the fringes

of Hitler's vast empire.

On a much larger scale, the Russians, with the help the of the "endless

steppe" and an extremely harsh winter, had stopped to bulk of the

Wehrmacht dead in its tracks. Meanwhile, the Americans and British in

North Africa were beginning to set the trap in which they could catch

and destroy Rommel's Afrika Korps. In France,

the Resistance, most violently carried out by the Communists, was hampering

German control of the area and was growing.

The German military planners knew they would soon be

on the defensive and wanted to make sure they had complete control over

all of Europe before the Allies tried to invade it. One glaring exception

to this complete control was Vichy France,

and on November 11, 1942 the Germans entered the area under the Vichy

regime's control without meeting any resistance. The Vichy government

was still allowed to function as it had before, but the Germans would

keep a closer eye on it and would conduct operations of their own within

Vichy's territory.

Exactly twenty-four years after his native Germany surrendered to France, Oberssturmfüher

(First Lieutenant) Klaus Barbie of the Gestapo entered

the city of Lyon. Barbie's orders were simple and strict: "...fight

and kill the Resistance" and rid Lyon of Jews.35 When the Gestapo assigned

Barbie to Lyon, an ancient city where both the Resistance and Jews could

easily hide, they knew they would not be disappointed. Before being

sent to Lyon, Barbie had proved himself an able and enthusiastic SS officer in Amsterdam where he earned a well-deserved reputation for

being both especially cunning and especially brutal. One time, when

he received orders to arrest two German-Jewish ice-cream peddlers, he

decided that a mere arrest would not satisfy his Nazi ideology. Instead

of arresting the two men, he decided to kill them on the spot. He killed

one man by bludgeoning him with an ashtray and the other he shot. For

his zeal, he was awarded the Iron Cross by his superiors.36 On a separate occasion, Barbie was given credit for rounding up and

dispatching over 200 "Zionists" when he tricked the local

Jewish Council into giving him the locations of hundreds of Jews who

were hiding in Amsterdam.37 Thus, when

the Gestapo needed to

pick a man to head their office in Lyon, the "Capital of the French

Resistance," Klaus Barbie with his cunning, language skills, and special zeal was a natural choice.

When Barbie arrived in Lyon, he immediately set up

shop in the elegant Hotel Terminus, which would serve as his base of

operations throughout his stay in Lyon. Although Barbie was comfortable

in his posh new headquarters, he had a tough job to do, and Lyon proved

to be his biggest challenge yet. Lyon had earned the nickname "Capital

of the Resistance" for several reasons: it had been under the relatively

lax control of the Vichy regime for two years, it was near Switzerland,

and it was a medieval city with more than enough winding streets, cul-de-sacs,

and secret basements to hide in. The job of "cleansing" Lyon

was far too large for the Gestapo to handle alone, but, as Barbie would soon discover, the natives had

already started his work for him.

During his time in Lyon, Klaus

Barbie was responsible for two of the most infamous acts the Nazis

committed in France. First was

the murder of Jean Moulin, Charles de Gaulle's right-hand man, and the

man who united the Resistance. Immediately after Moulin succeeded in

uniting the various factions of the Resistance, he went to meet the

leaders of Lyonnaise Resistance. Moulin was supposed to meet with several

of his most important allies but he found himself sharing a park bench

with none other than Klaus

Barbie. Following his arrest, Moulin would spend his days in Montluc

and his nights in a basement near Gestapo headquarters where he was tortured almost to the point of death by Barbie's

men, and probably by Barbie himself. After his final meeting with Barbie,

a half-dead Moulin was unceremoniously dumped in the courtyard of Montluc

Prison. As Christian Pineu, the prison's barber describes, Moulin was

in bad shape: "Moulin was unconscious, his eyes [were] pushed into

his skull as though they had been pushed through his head. A horrible

blue wound scarred his temple. A rattling sound came out of his swollen

lips."38 Within a week, Jean Moulin

succumbed to his wounds, and in dying, made Klaus

Barbie, his murderer, a name France would never forget. What makes Moulin's death even more tragic is that

he never would have been captured had he not been betrayed by his fellow

résistants. Even Klaus

Barbie later acknowledged that he would have never caught Moulin

had it not been for the help of Réné Hardy, one of Moulin's

comrades.39

The other crime for which Klaus

Barbie's name should never be forgotten was the "liquidation"

of a camp where Jewish children were hiding. The forty-four children,

most of whom were immigrants and all of whom were under the age of fourteen,

were living in an old boarding house in the tiny village of Izieu which

lies in the foothills not too far from Lyon. The camp, where the children

were being schooled while they were being hidden was run by the O.S.E.

(Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants - "Children's Welfare Organization")

, an organization that among other things ran camps to keep Jewish children

away from S.S.-infested areas.40 Thus,

it was not by chance that the O.S.E. picked Izieu, a sleepy little town

a few miles east of Lyon, for the location of a modest children's camp.

The town seemed friendly enough to their presence and there were relatively

few problems establishing a children's home there in late 1943.41 For several months the children, under the guardianship of half-a-dozen

adults, lived the bittersweet lives of homesick children. For the time

being, the children and their guardians, tucked away in an isolated

and friendly village, seemed perfectly safe from the goings on in the

outside world. Then, on April 6, 1944, actually Maundy Thursday, four

vehicles, three of which were lorries, pulled up in front of the house;

from those vehicles emerged Klaus

Barbie's Gestapo.

As a witness of the raid later recalled:

It was breakfast time. The children were in the

refectory drinking hot chocolate. I was on my way down the stairs

when I saw three trucks in the drive. My sister shouted to me: it's

the Germans, save yourself! I jumped out the window. I hid myself

in a bush in the garden...I heard the cries of the children that were

being kidnapped and I heard the shouts of the Nazis who were carrying

them away...They threw the children into the trucks like they were

sacks of potatoes. Most of them were crying, terrorized.42

Following the raid on their home in Izieu, the children

were shipped directly to the "collection center" in Drancy

by the Gestapo. Upon reaching

the at Drancy, the children were put on the first available train "towards

the East" and, of the forty-four children kidnapped by the Nazis

in Izieu, not a single one survived the journey. One survivor of Auschwitz

revealed during Barbie's trial what happened to the children:

I asked myself where were the children who arrived

with us? In the camp there wasn't a single child to be seen. Then

those who had been there for a while informed us of the reality. 'You

see that chimney, the one smoke never stops coming out of. . . you

smell that odor of burned flesh. . . ?' 43

As was the case in his capture of Jean Moulin, Barbie

was able to locate and conduct a surprise raid on the Izieu house because

a Frenchman saw it in his interests to help the Gestapo.

Without collaboration, the Gestapo,

which had never set foot in Izieu until the day of the raid, would have

never known about, let alone found, the house where the Jewish children

were staying. Someone, and nobody in the tight-knit community of Izieu

wants to say who, had gone out of his or her way to inform the Gestapo that there were Jews staying in Izieu.

Although they are his most well-known crimes, the murder

of Jean Moulin and the deportation of the forty-four children staying

in Izieu were certainly not Klaus

Barbie's only crimes. During his eighteen-month reign of terror

in Lyon, Klaus Barbie oversaw

the deportation of thousands of Jews and résistants from Lyon.

Most of those whom Barbie deported would never return, and, when Barbie

signed the orders to send people to Auschwitz, he knew full well what

would happen to them.44 One deportee distinctly

remembered the Gestapo officer who was leading him and hundreds of others onto a train saying

in broken French, "Where you're going it will be worse than death."45 For the prisoners who stayed in Lyon, life was not too much better.

A trip to Lyon's Montluc prison when Barbie was running it meant almost

certain death. When Barbie wanted to discourage the Resistance, he took

hostages, and when the Resistance ignored his warnings, the hostages

were lined up in Montluc's courtyard and shot.

Klaus Barbie did not just limit his activities to shootings and deportations. What

made Barbie such an effective Gestapo officer, and what made people afraid to try to assassinate him for fear

they would miss, was his use of torture. Most people who were tortured

by Barbie had similar experiences. Following their arrest, the prisoners

who had information or who had somehow angered the Gestapo,

were taken the elegant fourth-floor lounge of the Hotel Terminus for

"reinforced interrogation." As the prisoners sat in the lounge

waiting for their "interviews" with the Gestapo,

those who arrived a few hours earlier were paraded in front of them.

Often just seeing the mutilated bodies of one's comrades was enough

to make otherwise stubbornly brave people cooperate. Then, the prisoners

were taken one-by-one into one of the hotel's most luxurious suites

where they were beaten by club-wielding Gestapo men.46 Once the Gestapo broke enough of the prisoner's bones to make sure he or she would remain

sedentary for the interrogation session, they would leave the prisoner

alone for a few hours. For the most stubborn prisoners, Barbie resorted

to whipping, amputations, starvation, and the infamous "baths."

A bath at the Hotel Terminus meant being held under water in one of

the hotel's elaborately decorated baths until one fainted, then being

revived, then being asked questions, then being dunked again. As prisoners

were being tortured, a normal office operated in the background. As

André Frossard, a résistant captured by Barbie, the process

of being torture often had a level of absurdity rivaling the best fiction

of Sartre or Camus:

[I] was strung up by the hands and feet, then suspended

by a pole and immersed in cold water. And the strangest thing was

that everything was normal. Here you were hanging naked over a bathtub

while a secretary typed, and people told jokes, and someone smoked,

and someone munched on a sandwich, and someone else looked out the

window. 47

Barbie would have stayed in Lyon to the bitter end

of the German occupation of the city in September, 1944, but just before

Lyon fell, Barbie contracted a venereal disease and had to be hospitalized

in western Germany. As Barbie

was being driven to the hospital, his men were carrying out his last

order, emptying Montluc prison. Instead of fighting on the battlefield

to defend Lyon, Barbie's men rounded up their 70 remaining prisoners

and shot them. Among the dead were two priests.48 Within a week, Lyon fell, but by time the Allies captured Lyon, Barbie

was already in Germany and most

of his victims dead. When Barbie recovered from his illness a few months

later, he was released from the hospital, and that was the last time

anyone officially saw him for almost forty years.49

When the war ended, the Vichy regime was dissolved

and its leaders were tried as traitors. The beloved Pétain was

convicted but then pardoned, but Laval was excuted by a firing squad

on October 15, 1945. Until the very end, Laval firmly believed that

his collaboration with the Nazis was a patriotic act and he died shouting

"Viva La France!"50 Laval's view was held by many of his underlings and when the newly forming

Fourth Republic incorporated those who ran the Vichy regime into its

own adminstrative body, it chose to reconcile the two views of France by forgetting, not teaching or supressing. By forgetting, the Fourth

Republic dismissed the pain of those who suffered at the hands of Vichy

and set a precedent for future inconsistencies. Each time it forgot

though, the pain built, but more than forty years would pass before

that pain would see the light of day.

Klaus Barbie: Criminal

In Absentia (1945-1983)

Klaus Barbie was gone for almost forty years and in those forty years France changed a great deal. France had not only put the ambiguities of the Occupation behind her, but had

done the same for the colonial wars in Indochina and Algeria. The transition

back to democracy was not smooth, nor was the process of losing the

empire, and France decided that

the best way to cope with the inconsistencies of the past was to forget

about them as quickly as possible. In the name of progress, France forgot and forgave the sins of the Occupation, Indochina, and Algeria.

But, for each sin France forgave,

there were victims. There were victims of the Occupation, there were

victims of Indochina, and there were victims of Algeria. When the victims

cried for justice, France, the

land of the tricolor chose to ignore them. This, the victims neither

forgave nor forgot.

Like France, Klaus Barbie experienced

many changes during the forty years between his disappearance and his

trial. It turned out that Barbie did not just disappear on his own,

but had been smuggled out of Europe by the United States government.

(See FBI document on U.S. role in hiding Barbie) Immediately following Germany's surrender, Barbie

became a leading figure in a clandestine "resistance" organization

made up of other former SS officers who were at large and who wanted to prevent the former Reich

from falling into the hands of the Communists. The group planned to

approach the British and Americans and offer them "a strong experienced

corps of post-war leaders, loyal to Germany and opposed to Communism."51 In February,

1947, however, the American Counter-Intelligence Corps (C.I.C.) infiltrated

the organization and arrested all of its senior members, except for

Barbie, who eluded arrest by climbing out his bathroom window.52 The C.I.C., which was mainly concerned with countering Soviet espionage,

wanted to force the S.S. men to work for the Americans by arresting

them and then recruiting them through bribery and blackmail.53 Despite his escape, the C.I.C.'s offer of money and protection was too

much for Barbie to resist and he surrendered himself to a C.I.C. agent

in June, 1947.54 For the next two years Barbie would act

as a U.S. agent in Germany where

would live "very comfortably" and would receive "hundreds

of dollars" for his anti-communist activities.55 Then, in 1949, Barbie disappeared again.

An investigation by Allan A. Ryan, Jr. of the U.S.

State Department revealed that Barbie's disappearance in 1949 was sponsored

by the C.I.C., which wanted to use him as an anti-communist agent in

Bolivia.56 By 1951, the transformation

of Klaus Barbie from a Gestapo officer to an

American agent was complete, and he was living under the assumed name

of "Klaus Altmann" in Bolivia. In Bolivia, Barbie used his

identity as a former Gestapo officer to his advantage; if the C.I.C. ever tried to prosecute him

for his crimes during the war, he would embarrass the U.S. government

by revealing that he and others like him were on their payroll. With

the only people who knew of his identity and whereabouts silent, Barbie

was a free man.

In order to secure his place in Bolivia, Barbie often

performed services for Bolivia's various military regimes. When Hugo

"El Petiso" Banzer, one of Bolivia's most oppressive leaders,

came to power in 1971, he relied on Barbie's expertise to maintain his

unpopular rightist regime. That year, Banzer "gave total powers

to Klaus Altmann [Barbie] to concentrate on the creation of internment

camps for his [Banzer's] political opponents...torture and executions

were common in those camps." Many of Banzer's enemies were Communists

and Barbie probably saw no discontinuity between his activities in Lyons

and La Paz."57 Between 1951 and 1983,

Barbie also participated in drug-running schemes and even served as

an officer in the Bolivian secret police for a few years. When he was

not suppressing uprisings against Bolivia's various military regimes,

Barbie led a peaceful life as businessman and was an active socialite

in some La Paz circles. Aside from his activities in Bolivia, Barbie

also had a wife and children in Europe and he visited Europe on a regular

basis throughout the Fifties and Sixties to see them. On one visit he

even had the nerve to go on a sightseeing tour of Paris, where he had

been sentenced to death twice in absentia, in 1952 and 1954, by French

war crimes tribunals.

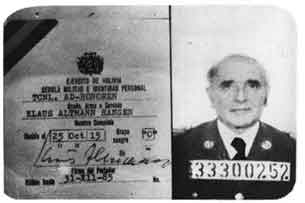

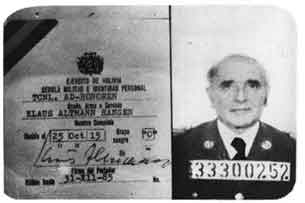

| Klaus

Barbie's ID card from when he was an officer in the Bolivian

secret police (Source: Children of Izieu). |

As Barbie transformed from a Gestapo agent into an American agent and then into a businessman and henchman

in Bolivia, he never gave up his Nazi ideology. Robert S. Taylor, an

American intelligence operative who recruited Nazis to work for the

C.I.C., described Barbie as "strongly anti-Communist and a Nazi

idealist who believes that he and his beliefs were betrayed by the Nazis

in power."58 Not only was Klaus

Barbie free, he was still a proud Nazi. Such a proud Nazi that in

1966 he was forcibly removed from the German club in La Paz for shouting

"Heil Hitler"

to an envoy from the West German government.59

While Barbie roamed South American and Europe, his

numerous victims and enemies began to look for him. Barbie's principle

adversary was Serge Klarsfeld, a French Jew who devoted much of his

adult life to hunting Nazis and bringing them to justice. Klarsfeld

himself was a survivor of the Holocaust but his survival would not have

been possible had it not been for the fatal sacrifice made by his father,

Arno Klarsfeld. When the SS swept through Nice on the night of September 30, 1943, to round up Jews,

the Klarsfelds hid behind a false wall in their apartment's coat closet.

Arno Klarsfeld, knowing how thoroughly the S.S. searched for hidden

people, realized that in order to save his family he had to prevent

the Nazis from examining the apartment too closely. He knew that if

the S.S. found his wife and children, they would almost certainly die,

but, as a healthy man who spoke German fluently and who had years of

experience as a manual laborer, he figured the Germans would put him

to work instead of simply killing him. When the Gestapo arrived, Arno was waiting for them and surrendered himself while his

family hid behind the closet. His gamble paid off and the SS left with their prisoner without bothering to thoroughly search the

apartment.60 The family was saved, but

it turned out that Arno Klarsfeld's guess was only partially correct.

He was right that his family would have been killed by the Nazis, and

he was right that as an able-bodied man the Nazis would put him to work.

He was wrong, however, to think he would survive. Arno Klarsfeld expected

hard work ahead of him, but not even the heartiest of men could survive

the notorious Furstengrube mines where he worked until his health was

destroyed by 36-hour work shifts and malnutrition. When he was worn

down to the point at which he could no longer work, Arno Klarsfeld was

sent to Auschwitz, where he disappeared in March 1944.61 For the young Serge Klarsfeld cowering in a closet and knowing that

he would never see his father again, the Nazis became his eternal enemies

and he vowed never to rest until they had all been brought to justice.

The other person responsible for the end Klaus

Barbie's life as a free man was Beatte Kunzel, the wife of Serge

Klarsfeld. Kunzel, a German whose father had served in the Wehrmacht,

was enraged that Nazis could go free "because of the apathy of

governments" and, like her husband, devoted her life to tracking

down these criminals.62 The Klarsfelds'

strategy was simple; they would flush a hidden Nazi criminal out of

hiding and then whip up public interest so that a trial could take place.

The really tricky part was not finding the Nazis or getting the public

enraged, but was getting the governments of the counties where the Nazis

were hiding to cooperate. In 1972, the Klarsfelds got a lucky break

when they stumbled across a secret report claiming that Klaus Altmann,

a German living in Bolivia, and Klaus

Barbie, the "Butcher of Lyons," were one and the same.63 While Serge worked his way through the French legal system, Beatte went

to La Paz and told the Bolivian press about Altmann/Barbie. Although

she succeeded in creating an uproar and in getting to French government

to ask formally for Barbie's extradition, Barbie was again saved from

answering to justice.

What saved Barbie in 1972 was the greed of Hugo Banzer,

the military dictator who ran the Bolivian government from 1971 to 1978.

Not only was Barbie one of Banzer's most valuable henchmen, he was a

potential form of currency. In essence, Banzer wanted to sell Barbie

to France for increased political

leverage, money, and weapons and because Barbie was valuable to both

Banzer and France, the price

was quite high.64 So high, in fact, that

the Pompidou administration refused to play Banzer's game. The relatively

conservative Pompidou administration had another reason for not purchasing

Barbie, they were perfectly content with Barbie staying in Bolivia where

he could not dredge up any unwanted memories.

Favorable circumstances saved Barbie in 1972, but it

was only a matter of time before both France and Bolivia saw it in their best interests to extradite him. Barbie's

time ran out in the early 1980s, when Banzer had been replaced by a

leftist regime who wanted to get rid of Barbie, and when Pompidou was

replaced by the liberal Mitterand administration which was eager to

take Barbie off of Bolivia's hands. In late 1982, the Bolivians had

lowered their demands but still wanted something in exchange for turning

over Barbie and surely it was no coincidence that the Bolivian president

received "a planeload of arms, three thousand tons of wheat, and

fifty million dollars" on his visit to Paris in 1983.65 With Barbie's "airfare" paid for, all that remained was the

actual extradition, but even in 1983 France was not truly prepared for Barbie's arrival, because with Barbie also

arrived the past.

For the Mitterand administration, Barbie's return seemed

like a no-lose situation. The administration figured that if they prosecuted Klaus Barbie, who was guilty

beyond the shadow of a doubt of some of the most heinous crimes of the

Occupation era, they would surely become more popular among their constituents.

When France brought justice to Klaus Barbie, it would

redeem all the wrongs and inconsistencies of the Occupation. Thus, it

was not just Barbie who was on trial but France itself. By confronting Barbie, France would be confronting its past and by punishing him, France would be conquering the past. And most importantly, it was a trial the

government thought it would certainly win.

For his victims and their relatives, Barbie's return

had even greater significance; justice finally seemed within grasp after

almost forty years of painful waiting. In 1983, Klaus

Barbie was the same man as forty years before. Never once over the

past forty years had Barbie apologized for his crimes, nor did he ever

show the slightest bit of remorse for them. Even in the late Seventies,

Barbie bragged to a journalist that he was proud of his role in Lyons

and he went so far as to claim he prevented France from falling to communism.66 Thus, the

only cure for many of the wounds Barbie had inflicted and then his irreverent

absence would be his punishment. Even the usually pessimistic French

press was caught up in the excitement. "He is going to pay, at

last!" boasted Le Monde's front page on February 7, 1983, the day

following Barbie's arrival in France.67 No group was more optimistic than the Left, though. Daniel Voguet, lawyer

for the Parti Communiste Française, was quite optimistic about

the upcoming trial: "The entire trial will be an accusation of

the Right. The French right-wing was in collaboration with the Germans."68 The PCF thus saw the trial as a chance to highlight its role in the

Resistance and for the first time ever it seemed as if the 150,000 Communists

who died during the Occupation would be vindicated. Whatever their political

outlook, most of the French media were looking forward to the trial

and promised that trial would be "long and spectacular."69 That was too true.

Although he did not know it when he was being taken

to a Bolivian prison for failing to repay a debt, Klaus

Barbie would play a key role in forcing France to confront her inconsistent past and present. What he did know was

that chances were pretty slim that his arrest was solely for the failure

to repay $10,000. To begin with, Barbie had already been sentenced to

death in absentia in 1952 and 1954 for his crimes against the Resistance

Under France's Statute of Limitations,

however, Barbie was no longer accountable for his past crimes and could

not be punished for them. The logic behind this law is that, if twenty

years passes between when a person is convicted for something and when

he is punished for it, there have been so many changes in the political

environment and the individual's life that punishment would be futile.

Over the course of twenty years a criminal might "go straight"

and raise a family and try to leave the past behind; likewise, what

was a crime twenty years ago, may not seem so bad in retrospect. Barbie,

who was sentenced to death twice in absentia by French military tribunals,

in 1952 and 1954, for his "war crimes," and who twenty years

after those trials, was still in Bolivia, could not be excluded from

the Statute of Limitations should he be tried under French law.70 Although he had escaped being punished for his war crimes, Barbie was

far from off the hook. Starting in 1972, when the Klarsfelds found Barbie

living under the name of Altmann in Bolivia, there was a considerable

push to try Barbie for a different set of crimes, those he conducted

against humanity. The Klarsfelds' success is illustrated by the shift

in the French government's attitude towards Barbie. In 1972, the French

government attempted to extradite Barbie for war crimes, that is, for

acts of violence against the Resistance, but by 1983 the Mitterand administration

extradited Barbie for his "crimes against humanity." To admit

that Barbie's crimes were against humanity was to give a new and well-deserved

weight to his crimes, but it was also to make any trial of Barbie that

much more sensitive. Although distance and time had saved Barbie from

paying for his crimes against the Resistance, the incircumscribability

of the Nuremburg laws made it impossible for him to escape being tried

for the torture, massacres, and deportation of civilians.

From his prison cell in La Paz, Barbie was taken to

the airport and flown to French Guiana where was put on a military plane

bound for Lyons. Once he figured out that the plane was going to France and not Germany as he had hoped,

Barbie "walled himself in silence."71 Maybe he thought that if he were quiet enough, the French would forget

about him, just as they had so conveniently forgotten about their own

past. He was not forgotten and when he arrived in Lyons on February

6, 1983, the whole world remembered who he was. Although the French

military had tried to keep the details of Barbie's flight secret, someone

leaked Barbie's itinerary to the press. By the time Barbie arrived in

Lyons, the police were struggling to restrain the angry crowds that

awaited Barbie at the airport. The emotions running through the crowd

were at a fever pitch and more than one person had come to the airport

with plans to kill Barbie. For instance, a woman who had been interned

in Drancy for three months bought a 22-caliber rifle just for the occasion.72 Unluckily for those who wanted to continue forgetting about the past,

she missed. Also at the airport that day was another group of people,

those trying to flee the memories brought back by Barbie's return. For

some, Barbie's return triggered unbearable flashbacks to the Occupation,

but many others feared that Barbie would denounce them collaborators

and shatter the lives they had constructed for themselves over the past

forty years.

When Barbie arrived back in Lyons, the memories of

the Occupation began to return and the general public became nervously

euphoric about finally getting the chance to confront one of the darkest,

most tragic chapters of their history face on. As was the case with

most trials of prominent Nazis, the trial of Klaus

Barbie was surrounded by a swarm of misconceptions. Like the trial

of Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the Final

Solution, the most prominent and most short-lived misconception

was that the trial would be an easy victory for the prosecution.73 The problem was that what Barbie and his fellow Nazis had done had caused

a great deal of pain and because that pain had gone unanswered for almost

forty years, it became even deeper. Repressed agony on a massive scale

makes for moral uneasiness and given the amount of memories they repressed,

it is fair to say that the French liked to avoid such uneasiness. To

paraphrase Erna Paris, in order to convict Barbie, France would have to open the door of the closet into which the truth about

Vichy had been so hurriedly shoved.74 Once

that door had been opened, it would remain that way until all its contents

had been exposed. Nervous or not, most French thought they were ready

to finally confront their past. What they did not know was how much

of the past they would confront, because far more than just the Occupation

was going to be brought up during Barbie's trial.

Preparing Barbie's Defense

(1983-1987)

During the first few days following Barbie's return,

it seemed that his upcoming trial would run along the lines of France versus the forces of evil. On the day after Barbie's arrival, Le Monde

printed a special section intended to educate the public on who Barbie

was and what he had done. The press emphasized two things the most:

that Barbie was the murderer of Jean Moulin and that Barbie had been

working for the Americans when he was in Bolivia. There was very little

mention of Barbie's role in the Final

Solution and even less mention of the French collaborators. Once

the papers tired of printing chronologies of Barbie's whereabouts and

the like, they opened up their pages to political writers and philosophers.

Instantly the mood changed from nervous glee to just nervousness. In

an article entitled "The Justice of Whom?" the prominent political

writer Gilbert Comte worried aloud that the Barbie trial would "demoralize

the youth of France more than

it instructs them."75 Opposite Comte's

article was a piece by Joseph Rovan, a former résistant and historian.

Rovan complained that the trial came too late and the only thing that

could come from it was pain. In Rovan's opinion the French would try

to place too much weight on the trial and act as if "Bolivia gave

us Hitler himself."

Doing that, feared Rovan, would hurt Franco-German relations, and would

ultimately hurt the French themselves.76 As the politicians and writers scrambled to have their views on Barbie

printed, perhaps the most poignant statement on Klaus

Barbie was one by Philip Potter, a pastor from the Antilles. Tucked

neatly under the continuation of a huge article about Jean Moulin's

death, a tiny side column several pages deep into February 11th's Le

Monde quoted Potter as saying:

In reality, Barbie and his like are the products of your [French] history. Hitler, Barbie, Eichmann

and company represent the end of the Aufklärung (century of Enlightenment)

which produced four things: the Industrial Revolution, which subordinated

man to the machine; the founding of the United States on a declaration

of independence where liberty and equality were applied to all men -

except for blacks and Indians; - the French Revolution of 1789 where

liberty brotherhood, and equality were indeed claimed by the bourgeoisie;

and imperialism based on racism. 77

It was racism, ironically justified by the principles

of the Enlightenment that created the Nazis and that same racism was

eternally bound to both the ideals of the Republic and the evils of

imperialism. What Potter both hoped for and feared was that Barbie's

reappearance would make those who were products of the Enlightenment,

that is, everyone, realize the pain their history had caused. Potter's

only mistake was that he spoke to soon, and three short days after Barbie's

arrival his voice was drowned in a sea of others.

When Barbie arrived in the Montluc Prison in Lyons, this time as a prisoner,

he was greeted by his lawyer, Alain de la Servette, head of the Lyons

Bar Association. De la Servette, a fairly liberal lawyer of "impeccable

reputation" had, like many of his peers, volunteered to defend

Barbie. For a young aspiring lawyer, the Barbie trial could be the chance

of a lifetime, but de la Servette had already succeeded and though he

stood to gain much respect from his peers for taking such a tough case,

what he really wanted was a fair trial.78 De la Servette, who had a great deal of experience in criminal law was

concerned that because the evidence was overwhelmingly against Barbie

and because the charges were so serious, the accused would not be able

to receive a fair trial in a country quite hostile to his presence.

If Barbie was to be convicted under French law, then he must enjoy its

benefits as well. Of all of France's

lawyers, de la Servette believed he was the one most qualified to defend

Barbie because he had experience, because he avoided politics, and because

he had a sense of judicial fairness. If justice were to prevail during

the Barbie trial, claimed de la Servette, then that trial must be fair.

Unlike all the others who volunteered to defend Barbie, de la Servette,

as head of the Lyons Bar Association, was in charge of picking a lawyer

for Barbie, so he picked himself for the job.

Keeping with his desire to see Barbie receive a fair