France Virtual Jewish History Tour

|

Throughout the country’s stormy history - from the Roman period through the present – Jews have lived in France, their fate intimately tied to the various kings and leaders. Despite physical hardship and anti-Semitism, Jewish intellectual and spiritual life flourished, producing some of the most famous Jewish rabbis and thinkers, including Rashi and Rabenu Tam.

Jews have contributed to all aspects of French culture and society and excelled in finance, medicine, theater, and literature. Currently, France hosts Europe’s largest Jewish community—440,000 strong—and Paris is said to have more kosher restaurants than even New York City. As anti-Semitism has spiked in France, thousands of French Jews have made aliyah.

|

Learn More - Cities of France: |

Roman-Medieval Period

Middle Ages

French Revolution & Restoration

Early 20th Century

The Holocaust

Post-Holocaust Era

Modern Community

Threats to the Community in the 21st Century

Islamic Terror

Anti-Zionism Cloaked as Anti-Semitism

Protests Against Anti-Semitism

Relations with Israel

Jewish Tourist Sites

Roman Period to the Medieval Period

A Jewish presence existed in France during the Roman period, but the community mainly consisted of isolated individuals rather than an established community. After the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, boats filled with Jewish captives landed in Bordeaux, Arles, and Lyons. Archeological finds of Jewish objects with menorahs imprinted on them date back to the first through the fifth century.

Jewish communities have been documented in 465 in Vannes (Brittany), in 524 in Valence, and in 533 in Orléans. Jewish immigration increased during this period, and attempts were made to convert the Jews to Christianity.

In the 6th century, a Jewish community thrived in Paris. A synagogue was built on the Ile de la Cite but was later torn down and a church was erected instead.

Anti-Jewish sentiments were not common in this early period; in fact, after a Jewish man was killed in Paris in the 7th century, a Christian mob avenged his death.

During the 8th century, Jews were active in commerce and medicine. The Carolingian emperors allowed Jews to become accredited purveyors in the imperial court. Jews also became involved in agriculture and dominated the field of viticulture; they even provided the wine for Mass.

The Middle Ages

The First Crusade (1096-99) had no immediate effect on the Jews of France; however, in Rouen, statements were made by the Crusaders justifying their persecution of Jews across Europe.

After the Second Crusade (1147-49), a long period of persecution began. French clergymen gave frequent anti-Semitic sermons. In some cities, such as Beziers, Jews were forced to pay a special tax every Palm Sunday. In Toulouse, Jewish representatives had to go to the cathedral weekly to have their ears boxed as a reminder of their guilt. France’s first blood libel took place in Blois in 1171, and 31 Jews were burned at the stake.

The situation deteriorated during the rule of King Philip Augustus. Philip was raised believing that Jews killed Christians and, therefore, held an ingrained hatred toward the Jews. After four months in power, Philip imprisoned all the Jews in his lands and demanded a ransom for their release. In 1181, he annulled all loans made by Jews to Christians and took a percentage for himself. A year later, he confiscated all Jewish property and expelled the Jews from Paris; he readmitted them in 1198, only after another ransom was paid and a taxation scheme was set up to procure funds for himself.

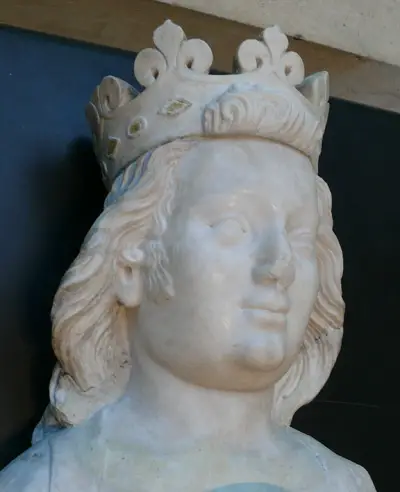

Philip IV the Fair from Recueil des rois de France, by Jean Du Tillet (1550) |

In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council forced Jews to wear a badge in the provinces of Languedoc, Normandy, and Provence.

More anti-Jewish persecutions took place in the western provinces during the rule of Louis IX (1226-70). In 1236, crusaders attacked the Jewish communities of Anjou and Poitou and tried to baptize all the Jews; those who resisted were killed. An estimated 3,000 Jews were murdered.

In 1240, Jews were expelled from Brittany, and the famous disputation of the Talmud began in Paris on June 12. The Talmud was put on trial and was subsequently burned in 1242. Despite the persecution, Jews managed to remain active in moneylending and commerce. Jews expelled from England were also admitted into France. Again, in 1254, Jews were banished from France, and their property and synagogues were confiscated; however, after a couple of years, they were readmitted.

Phillip IV, “The Fair,” ascended to power in 1285. In 1305, he imprisoned all the Jews and seized everything they owned except the clothing on their backs. He expelled 100,000 Jews from France and allowed them to travel with only one day’s provisions.

Charles IV |

Phillip IV’s successor, Louis X, allowed the Jews to return in 1315.

On June 24, 1322, Charles IV, “The Fair,” the son of Phillip IV, expelled all the Jews from France without the promised one-year warning.

Between 1338 and 1347, 25 Jewish communities in Alsace were victims of terror. Massacres in response to the Black Plague (1348-49) struck Jewish communities throughout the east and southeast. The Jews of Avignon and Comtat Venaissin were spared similar fates because of intervention from the pope. Further bloodshed spread to Paris and Nantes in 1380. The culmination of all the persecution and bloodshed was the definitive expulsion of Jews from France in 1394.

A Jewish presence was first mentioned in Besançon, in eastern France, in 1245. Jews left the town in the 15th century and returned only after the French Revolution. Jews were first permitted to reside in Belfort, the capital of the Belfort region in eastern France, in the 1300s. By the time of the Nazi occupation, there were 700 Jews in the town, of which 245 were killed.

Despite all the expulsions and persecutions, Jewish learning thrived during the Middle Ages. Il-de-France and Champagne became centers for Jewish scholarship, and other centers of learning grew in the Loir Valley, Languedoc, and Provence. In the north, Talmudic and biblical commentary, as well as anti-Christian polemic and liturgical poetry, were studied. In the South, grammar, linguistics, philosophy, and science were studied. Also, in the South, numerous translations were made of religious materials from Arabic and from Latin to French.

One of the foremost Jewish scholars during the Middle Ages was Rashi, who started his own yeshiva in France. His biblical commentary is among the most popular and widely known works today.

Many Marranos, secret Jews from Portugal, came to France in the mid-1500s. Most did not remain faithful to Judaism and assimilated into French society. This was the first time since 1394 that Jews were allowed to live legally in the kingdom of France.

After the Chmielnicki massacres in 1648, more Jewish settlers, fleeing Ukraine and Poland, came to Alsace and Lorraine. An influx of immigrants came to southeast France when the Duke of Savoy issued an edict declaring Nice and Villefranche-de-Conflent free ports.

The communities of Avignon and Comtat Venaissin flourished in the 17th century. Jews became involved in commercial activity and frequently attended fairs and markets. Success spread to other nearby communities, including the Jewish community of Alsace, who exploited the facilities given to the Marranos, “Portuguese Jews.”

Jews began resettling in Paris in the 18th century. Two groups of Jews came to Paris: southern Jews mainly of Sephardic descent from Bordeaux, Avignon, and Comtat Venaissin and Ashkenazim from Alsace, Lorraine, and other northern cities. The wealthier Sephardim settled on the Left Bank, while the Ashkenazim settled on the Right. Paris’s first kosher inn opened in 1721, and its first synagogue opened in 1788.

Anti-Jewish laws began to be repealed in the 1780s, such as the “body tax,” which likened Jews to cattle.

French Revolution & Restoration

|

About 500 Jews were living in Paris and about 40,000 in France at the time of the French Revolution, which began with the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, and lasted for more than ten years.

On December 23, 1789, a three-date debate on Jewish rights began in the National Assembly. Count Stanislas de Claremont-Tonnerre declared, “The Jews should be denied everything as a nation but granted everything as individuals.” Abbe Jean Siffrein Maury said, “I observe first that the word Jew is not the name of a sect, but of a nation that has laws which it has always followed and still wishes to follow. Calling Jews citizens would be like saying that without letters of naturalization and without ceasing to be English and Danish, the English and Danish could become French.” Robespierre commented, “The evil qualities of the Jews emanate from the degree of humiliation to which you have subjected them…any citizen who fulfills the conditions you have laid down, has the right to public office.”

No conclusion was reached following the debate; nevertheless, the Sephardim received citizenship on January 28, 1790, and the Ashkenazim received it about six months later. Jews were given civic rights as individuals but lost their group privileges.

During the Reign of Terror (1793-94), synagogues, communal organizations, and other religious institutions were closed.

Napoleon considered the Jews “a nation with a nation,” and he decided to create a Jewish communal structure sanctioned by the state. Hence, in 1806, he ordered the convening of a Grand Sanhedrin, composed of 45 rabbis and 26 laymen. The Grand Sanhedrin paved the way for the formation of the consistorial system, which were religious bodies established in every department of France that had a Jewish population numbering more than 2,000. The consistorial system made Judaism a recognized religion and placed it under government control.

Despite the newfound freedoms, anti-Jewish measures were passed in 1808. Napoleon declared all debts with Jews annulled, reduced, or postponed, which caused the near ruin of the Jewish community. Restrictions were also placed on where Jews could live to assimilate them into French society.

The Jews did not receive the Restoration with any hostility. Jewish educational institutions were established. In 1818, schools were opened in Metz, Strasbourg, and Colmar. Other Jewish schools were opened in Bordeaux and Paris. The Metz Yeshiva closed during the Revolution and was reopened as a central rabbinical seminary. The seminary was transferred to Paris in 1859, where it continues to function today. Judaism was given the same status as other recognized religions.

During the 19th century, Jews were extremely active in many spheres of French society. Rachel and Sarah Bernhardt are two Jewish women who became famous for acting at the Comedie Francaise in Paris. Bernhardt eventually directed plays at her theater, and was called “Divine Sarah” by Victor Hugo.

Jews became involved in politics; for example, Achille Fould and Isaac Cremiuex served in the Chamber of Deputies. Jews also excelled in finance; two leading families were the Rothschild and the Pereire families.

In literature and philosophy, well-known Jews included Emile Durkheim, Marcel Proust, and Salomon Munk.

While the situation improved for Jews in France, the Damascus Affair served as a rude awakening. The accusation of a blood libel in Damascus led to an outbreak of anti-Jewish disorders in France in 1848. General unrest led to attacks in Alsace and spread northward; Jewish houses were pillaged, and the army had to be sent in to resume order.

|

|

The 1870 war transferred the Jewish communities of Alsace and Lorraine from French control to German control, a major loss for the Jewish community.

An upsurge of anti-Semitism began in the late 1800s. Anti-Semitic newspapers were circulated, including Edouard Drumont’s La France Juive (1886), which became a best-seller. Jews were blamed for the collapse of the Union Generale, a leading Catholic bank.

In this atmosphere, the infamous Dreyfus case was tried. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was arrested on October 15, 1894, for spying for Germany. He received a life sentence on Devil’s Island off the coast of South America. The government chose to repress evidence, which came to light through the writings of Emile Zola (J’Accuse...! (I Accuse)) and Jean Jaures. Ten years later, the French government fell, and Dreyfus was declared innocent. The Dreyfus case shocked Jewry worldwide and motivated Theodor Herzl to write the book “The Jewish State: A Modern Solution to the Jewish Question” in 1896. The Dreyfus case also led to the French law in 1905 separating church and state.

In October 2021, the Dreyfus Museum opened in the Paris suburb Médan. The museum contains documents, photos, court papers, and personal objects related to the Dreyfus Affair. The museum is in the Zola House, a cultural institution devoted to preserving the memory of Émile Zola. The director of the museum and institution, Louis Gautier, said the new space “will show and tell about the affair but also pose questions on vital issues of tolerance, othering, human rights, women’s rights, the separation of church and state and the contract between the republic and its citizens.”

Early 20th Century

At the turn of the century, Jewish artists, including Modigliani, Soutine, Kisling, Pissarro, and Chagall, were highly prominent.

France faced an increase in Jewish immigration in the early 1900s. More than 25,000 Jews came to France between 1881 and 1914. Immigrants hailed from all over Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Although, for many of the immigrants, France served as a transit point rather than a final destination.

The advent of World War I halted Jewish immigration and also put an end to anti-Semitic campaigns because of the need for a unified front. France was able to regain Alsace and Lorraine and many Jewish families were able to reunite once Alsace and Lorraine became part of France.

During the inter-war years, Jewish immigration from North Africa, Turkey, and Greece increased once again. Immigration from Eastern Europe also skyrocketed; many came after the pogroms in Ukraine and Poland. The trend continued, especially after the United States prohibited free immigration in 1924.

The Federation des Societes Juif de France (FSJF) was established in 1923 to take care of the needs of the French Jewish community.

On June 4, 1936, Leon Blum became the first Jew elected prime minister of France. He served just a year but returned to power in 1938; this time, his government lasted less than a month (March 13-April 10, 1938). After the war, he briefly served as prime minister again (December 16, 1946-January 22, 1947) in the transitional postwar coalition government.

The Holocaust

|

|

The Germans invaded France on May 10, 1940, and Paris fell on June 14. Two weeks later, the armistice was signed, France was divided into unoccupied and occupied zones, and Alsace-Lorraine was annexed to the Reich. A Vichy government was set up in France. An estimated 300,000 Jews lived in France before the invasion.

Until the German occupation of France in 1940, no roundup of Jews would have been possible because no census listing religions had been taken in France since 1874. A German ordinance on September 21, 1940, however, forced Jewish people of the occupied zone to register at a police station. These files were then given to the Gestapo.

Between September 1940 and June 1942, several anti-Jewish measures were passed, including expanding the category of who is a Jew, forbidding free negotiation of Jewish-owned capital, confiscating radios in Jewish possession, executing and deporting Jewish members of the resistance movement, establishing a curfew, banning a change of residence, ordering all Jews to wear a yellow badge and prohibiting access to a public area.

The Vichy government established a Commissariat General aux Questions Juives in April 1941 that worked with German authorities to Aryanize Jewish businesses in the occupied zone. French Jewry was represented in the Union Generale des Israelites de France (UGIF) during the occupation. Non-French Jews living in France were treated differently than French Jews during this period. Non-French Jews were rounded up for deportation by the French police, whereas French Jews were rounded up by the Gestapo, who did not trust the French authorities to do so.

In March 1942, the first convoy of 1,112 Jews was deported to concentration camps in Poland and Germany.

Beginning at 4:00 a.m. on July 16, 1942, 13,152 Jews were arrested, including 5,802 (44%) women and 4,051 (31%) children. The Vel’ d’Hiv roundup, codenamed Opération Vent Printanier (“Operation Spring Breeze”), was one of several Nazi-directed raids carried out by the French police aimed at eradicating the Jewish population in France. The name is derived from the nickname of the bicycle velodrome and stadium, where most of the victims were temporarily confined. Others were sent to the Drancy, Pithiviers, and Beaune-la-Rolande internment camps. All were subsequently transported in cattle cars to Auschwitz for their mass murder.

The Jews could take only a blanket, a sweater, a pair of shoes, and two shirts with them. Most families were split up and never reunited. The roundup accounted for more than one-quarter of the 42,000 Jews sent from France to Auschwitz in 1942, of whom only 811 returned to France at the end of the war.

Another notorious round-up occurred on August 15, 1942, when 7,000 foreign Jews were arrested and handed over to the Germans. Between 1942 and July 1944, nearly 76,00 Jews were deported to concentration camps in the East via French transit camps, and only 2,500 returned. Of those deported, 23,000 had French nationality; the rest were “stateless.”

France’s major transit camp, Drancy, located outside Paris, was established in 1941. Several other transit camps were created throughout France and were run by the French police. Drancy was designed to hold 700 people, but at its peak in 1940, it held more than 7,000. Drancy served as a stopping point for thousands of Jews en route to Auschwitz.

There were also concentration camps located inside France, such as Gurs, which opened in June 1940. By 1941, it housed about 15,000 inmates, including foreign Jews; many perished there from malnutrition and bad sanitation. More than 3,000 Jews died in these internment camps. When Germany occupied all of France in late 1942, most of the inmates were sent to concentration camps in Germany and Poland. After the deportations ended in mid-1943, only 1,200 prisoners remained.

It is estimated that 25 percent of French Jewry died in the Holocaust.

Several of the men responsible for the deportation of French Jews were later brought to trial:

Post-Holocaust Era

France became a haven for postwar refugees, and within 25 years, its Jewish population had tripled. In 1945, 180,000 Jews were living in France, and by 1951, the population reached 250,000. An influx of North African Jews immigrated to France in the 1950s due to the decline of the French empire. Subsequent waves of immigration followed the Six-Day War when another 16,000 Moroccan and Tunisian Jews settled in France. Hence, by 1968, Sephardic Jews were the majority in France. These new immigrants were already culturally French and needed little time to adjust to French society.

Two of the major problems facing French Jewry are assimilation and anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism has been present throughout France’s post-war history. After the Six-Day War in 1967, anti-Israel stances were taken by de Gaulle and his government. Anti-Israel propaganda was published in May 1968 by the New Left and supporters of Palestinian terrorism; several physical clashes broke out between Jews and Arabs in certain quarters of Paris. This atmosphere increased the aliyah of French and Algerian Jews in the late 1960s.

In the late ’70s, a spate of racist and anti-Semitic attacks were carried out against Jewish monuments and cemeteries. On October 3, 1980, a bomb exploded outside a Paris synagogue, killing four people. Terrorism and anti-Semitism continued to be a problem in the 1980s and 90s, as many synagogues, cemeteries, and restaurants were vandalized and desecrated. Few of the perpetrators have been apprehended.

In the late 1990s, Jews were concerned about the rise to power of the National Front political party, which espouses anti-immigration and anti-Semitic views.

Besides problems with anti-Semitism, France has had difficulty owning up to its role in the Holocaust. It took many years to apprehend and try French war criminals. Serge and Beate Klarsfeld played major roles in finding many of the Nazis and collaborators and bringing them to justice.

In the 1980s, a trial was held against Klaus Barbie, who received a sentence of life imprisonment. In 1994, Paul Touvie, who was responsible for the massacre of seven Jews in Lyon during World War II, was tried and condemned to life in prison. A third trial, in 1997, tried Maurice Papon, a senior official responsible for Jewish affairs in Bordeaux. Papon’s trial was different than the other two because the other two were killers, whereas Papon was a bureaucrat who signed the death warrants for 1,560 French Jews, including 223 children. Papon was found guilty of crimes against humanity and was sentenced to ten years in jail. The trial served as a pretext for reexamining France’s role in the Holocaust. Debate arose about the Vichy regime’s involvement in rounding up, deporting, and murdering French Jews.

Restitution for stolen-era artwork from France is another issue of controversy. In 1998, France finally created a centralized body to investigate Holocaust restitution cases for heirs and descendants of those whose property was confiscated during World War II. France’s national museum is trying to track down the owners or heirs to more than 2,000 pieces of unclaimed artwork in its possession. It is estimated that over 100,000 pieces of artwork were taken from Jews and others in France alone; Jewish art collections in France were among those coveted by the Nazis.

|

|

After decades of denying the French role in the deportations of Jews during the war, French President Jacques Chirac apologized in 1995 for the complicit role that French policemen and civil servants served in the Vel’ d’Hiv raid. In 2017, President Emmanuel Macron denounced his country’s role in the Holocaust and the historical revisionism that denied France’s responsibility for the 1942 roundup. “It was indeed France that organized this [roundup],” he said. “Not a single German took part.”

A plaque marking the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup was placed at 8 Boulevard de Grenelle in 1959. Another was placed at the Bir-Hakeim station of the Paris Métro on July 20, 2008. In 1994, a monument to those deported was erected on the edge of the Quai de Grenelle. The sculpture includes children, a pregnant woman, and a sick man. The French inscription says: “The French Republic pays homage to the victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecutions and crimes against humanity committed under the so-called ‘Government of the State of France’ 1940-1944. Let us never forget.”

On December 11, 2005, a memorial to 86 Jewish victims of Nazi physician August Hirt was unveiled at the Jewish cemetery in Kronenbourg.

A Holocaust memorial museum was opened in 2012. It provides details of the persecution of the Jews in France and many personal mementos of inmates before their deportation to Auschwitz.

A memorial was also constructed in 1976 at the site of the Drancy internment camp. A railway wagon used to carry internees to Auschwitz is also displayed at Drancy.

At the inauguration of a new Holocaust museum in Pithiviers in July 2022, Macron said of France’s behavior during the war: “Those dark hours have forever stained our history…France at that time committed the unforgivable.”

The Vichy regime, Macron added, “betrayed its own children eight decades ago and delivered them to their murderers. France now has a duty, in order to remain true to itself, to acknowledge this and to cede no inch to the present-day anti-Semitism.”

Modern Community

Today, of the 460,000 Jews in France, 277,000 live in Paris. There are 230 Jewish communities in France, including Paris, Marseilles (70,000), Lyons (25,000), Toulouse, Nice, and Strasbourg.

The Consistoire Central Israelite de France et d’Algerie reopened following the war. It is responsible for training and appointing rabbis, providing religious instruction for youth, supervising kashrut, and applying Jewish law in personal matters. The Consistoire mainly represents Orthodox synagogues, so several liberal synagogues fall outside its jurisdiction.

Another major organization, the Conseil Representaif des Juifs de France (CRIF), was founded in 1944. Today, it is comprised of 27 Jewish organizations, from Zionist to socialist. Since 1945, it has played a significant role in the fight against anti-Semitism.

The major Jewish community organization is the Fods Social Juif Unife (FSJU), founded in 1949. It is involved in social, cultural, and educational enterprises, as well as fundraising. The FSJU’s community centers played a large role in the absorption process of new Jewish immigrants.

Only 40% of French Jewry is associated with one of these community bodies. It is also estimated that only 15 percent of French Jews go to synagogue. Still, Jewish life and culture are flourishing. There are more than 40 Jewish weekly and monthly publications, as well as numerous Jewish youth movements and organizations.

Most French Jews send their children to public schools, although there is increased attendance in Hebrew day schools; today, nearly 25% of school-age children attend full-time Jewish schools. In Paris alone, there are 20 Jewish schools in the day school system. Hebrew is also being offered as a foreign language in many state high schools. In 1985, a new library sponsored by the Alliance Israelite Universelle (AIU) opened. It is now the largest Jewish library in Europe.

During the 1980s, there was a rise in the number of ultra-Orthodox Jews in France, especially in Paris. The Lubavitch movement has done much outreach work in France, putting up billboards during holidays and holding public candle-lighting ceremonies on Chanukah.

There is also a bilingual English-speaking community in Paris called Kehilat Gesher. Kehilat Gesher, a community of around 145 families, is the only French Anglophone liberal synagogue serving the greater Paris area through two locations, Paris 17th and St-Germain-en-Laye.

The best high schools in France are Jewish schools, according to a comprehensive report ranking all of France’s 4,300 high schools released in April 2015 by Le Parisien Daily. Beth Hanna High School, part of France’s Chabad Lubavitch school network, was ranked as the top school in the entire country due to its impressive 99% success rate on matriculation exams. The Jewish high school, The Lycee Alliance, was also ranked highly. Many lists from other reputable sources, including Le Figaro, ranked the Jewish schools as some of the top-performing schools in the country.

Threats to the Community in the 21st Century

For many years following the Holocaust, anti-Semitism in France was only a mild problem, but in the late 2000s, the Jewish Community Protection Services reported a strong surge in anti-Semitic incidents and attacks. From 2008 to 2010, there was a nearly 75% increase in anti-Semitic incidents, many attributed to anger over Israel’s Operation Cast Lead in the Gaza Strip and the ongoing conflict with the Palestinians.

Violence in France, especially directed at Jews, has been primarily perpetrated by Muslims. An estimated eight million Muslims live in France, compared to fewer than 500,000 Jews, and a large segment of that Muslim population has not successfully integrated into French society. Some came with radical views, and others have become more extreme because of contact with Islamists inside and outside of France.

In 2011, an estimated 389 incidents of anti-Semitism were reported, and the severity of the threat to Jews grew to the point where Jews were discouraged from wearing clothes or jewelry or anything that might identify them as Jews.

On March 19, 2012, a radical Muslim fired at children entering a Jewish school in Toulouse, killing a 30-year-old teacher and his three- and six-year-old children. A third child, aged eight, was also murdered, and a 17-year-old student was seriously injured. After that deadly attack, 90 anti-Semitic attacks were recorded in the next ten days. In October, a kosher grocery store was bombed in Sarcelles, wounding two people. Overall, France saw an increase of 58 percent in anti-Semitic incidents in 2012 compared to the previous year, according to a study released in February 2013 by the SPCD, the security unit of France’s Jewish communities. In addition, a 2012 Anti-Defamation League poll in France found that 58 percent of the respondents believed their government was not doing enough to ensure the safety and security of its Jewish citizens. [Click here for more French public opinion regarding Jews and Israel.]

The situation continued to deteriorate. According to a survey conducted by the Foundation for Political Innovation released in November 2014, 16 percent of France’s citizens believe there is a “Zionist conspiracy on a global scale.” One-fourth of the respondents said that “Zionism is an international organization that seeks to influence the world and society in favor of the Jews.” Out of all the individuals surveyed, 35 percent said that “Jews today, in their own interest, exploit their status as victims of the Nazi genocide during WWII,” and 25 percent stated that “Jews have too much power in the fields of economy and finance.”

In May 2022, following the reelection of President Macron, Élisabeth Borne was appointed France’s first female prime minister in more than 30 years. Her father was a Holocaust survivor. She resigned in January 2024 over disagreements with Macron related to immigration policy. She was replaced by Education Minister Gabriel Attal, who, at 34, is the country’s youngest-ever prime minister and its first to be openly gay.

Attal was raised Russian Orthodox Christian, his mother’s faith, but was also influenced by his Jewish father, who had relatives deported during World War II.

Following the right-wing National Rally Party’s success in the French parliamentary elections in 2024, Grande Synagogue of Paris Chief Rabbi Moshe Sebbag expressed concern about the future of Jews in France, urging youth to consider emigrating to Israel or safer countries. Sebbag highlighted the rising antisemitism linked to societal changes and mass immigration, noting the far Right’s growth and the Left’s recent antisemitic tendencies.

In the French elections on July 7, 2024, the far left unexpectedly gained significant seats in parliament, heightening concerns within the French Jewish community due to the left-wing elements that have anti-Israel and pro-Hamas stances. In response to the changing political landscape and growing apprehensions about the future, many Jews are turning to aliyah organizations to explore their options. Studies show that 38% of French Jews are considering making aliyah, translating to roughly 200,000 people, with 13%, or about 60,000 people, seriously considering it.

A May 2025 IMPACT-se report examines how French history textbooks and curricula depict Jews, Judaism, anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While the materials largely align with UNESCO standards, particularly in Holocaust education and the framing of Israel’s founding, significant gaps remain. Jewish history is often reduced to victimhood, with little attention to Jewish contributions to French society or the deep historical connection to Israel. Ancient Judaism is treated mainly as a precursor to other religions, and modern Jewish voices are underrepresented. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is oversimplified, and key historical nuances are missing. The report offers targeted recommendations to improve historical balance and representation.

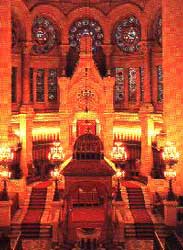

Islamic Terror

The entire French nation was traumatized on January 7, 2015, when two Islamic extremists attacked a French satirical newspaper that had published cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, killing 10 members of the staff and two police officers. Two days later, while police surrounded the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, an assailant believed to have killed a policewoman the day before took hostages at a Kosher supermarket in eastern Paris. After murdering four of the hostages, the suspect was killed when police stormed the market. During the siege, Jewish schools and shops in the neighborhood were closed, and, for the first time since World War II, the Grand Synagogue of Paris was closed for Friday prayers.

Three soldiers patrolling outside of a Jewish Community Center in Nice, Southern France, were attacked by an individual wielding a knife on February 3, 2015. The attacker was identified as 30-year-old Mousa Coulibaly (no relation to the Kosher supermarket gunman Ahmed Coulibaly) and had been expelled from Turkey during the previous week. Earlier that afternoon he had been riding on a tram in France when a tram employee approached him and could not produce a ticket. He was forced off of the train at the next stop, where he became irate and targeted the soldiers, slashing one soldier on the cheek, a second soldier on one of their legs, and a third soldier on the chin. He flew to Turkey on January 28 with a one-way ticket, which raised suspicions with French authorities who asked the Turkish government to send him back.

On November 13, 2015, terrorists affiliated with the Islamic State carried out a planned and coordinated terror attack on seven separate targets in Paris, France. The first attack occurred at the Stade de France, the country’s national sports stadium. At a friendly football match (not played for rank) between France and Germany attended by French President Francois Hollande, a bomber detonated himself outside of the stadium at 9:20 pm local time after a venue security guard discovered his explosive vest. A second bomber did not attempt to enter the stadium and detonated himself a few moments after the first explosion. It is a popular practice for fans to light firecrackers during the games, so the crowd was not dispersed, and the teams kept playing following the initial explosions. President Hollande was evacuated immediately, and once security inside the stadium realized what was happening, they stopped the game and had the fans come onto the field. A third bomber detonated himself at a McDonald’s restaurant close to the stadium thirty-three minutes after the second stadium bomber detonated.

At 9:20 p.m., almost simultaneous with the first suicide bomb detonation at the Stade de France, attackers opened fire at people eating dinner at Le Carillon cafe and Le Petit Cambodge on streets rue Bichat and rue Alibert. The assailants fled in two vehicles following the attack, in which they killed eleven people. Twelve minutes after the start of this attack, at 9:32 pm, an attacker opened fire on the Cafe Bonne Biere, killing five and injuring eight. Four minutes later, at nearby restaurant La Belle Equipe, multiple terrorists opened fire, killing nineteen and wounding nine others before fleeing in vehicles. At 9:40 p.m., a suicide bomber was seated at the Comptoir Voltaire cafe and placed an order before detonating his explosives, killing himself and seriously injuring fifteen.

U.S. blues-rock band The Eagles of Death Metal was playing a sold-out show at the Bataclan Theater on Boulevard Voltaire when, at approximately 9:45 p.m., three men dressed in all-black toting AK-47 assault rifles entered the concert hall. Shouts of “Allahu Akbar” were heard, and the gunmen started firing calmly into the crowd. Some concertgoers initially mistook the machine-gun fire for pyrotechnics, but it soon became apparent that they were in danger. The initial attack lasted for 10-20 minutes, with the attackers re-loading three or four times each while lobbing grenades into the frenzied crowd. Band members managed to escape the theater soon after the attack began, but some of their crew members were killed. The attackers started to round up a group of 60-100 hostages at 11:00 pm, and shortly after midnight, French police launched an assault on the Bataclan theater. Two terrorists detonated their suicide vests when police stormed the building; police shot one, and one escaped. The terrorists at the Bataclan theater killed eighty-seven people. Syrian and Egyptian passports were found on the bodies of the attackers, but these proved to be fake. In total, these attacks killed 129 people and injured over 350.

A state of emergency was declared in France by President Hollande in the days after the attack, which was then extended until the beginning of 2016. The French army carried out its largest air strikes on ISIS on November 15, 2015, dropping 20 bombs on the self-proclaimed capital in Raqqa. Hollande vowed to “mercilessly” fight terrorism while on a visit to the Bataclan theater after the attacks.

During the first half of 2015, there was an 84% increase in anti-Semitic attacks compared with the same period the previous year. Although Jews make up less than 1% of France’s population, more than 50% of all reported racist attacks in France in 2015 were perpetrated against Jews.

A rabbi and his son were attacked outside of a synagogue in Marseille in mid-October 2015. In an interview after the fact, the Rabbi clarified details about the attack; for example, the attacker was allegedly drunk and stumbling. A Jewish schoolteacher in Marseille, France, was stabbed multiple times by youths professing allegiance to the Islamic State on November 18, 2015. Three teenagers, one wearing a shirt bearing the symbol of ISIS, approached the teacher on the street and taunted, insulted, and finally stabbed the victim three times before being chased away by a car.

On January 11, 2016, a 35-year-old Jewish teacher who was wearing a traditional Jewish skullcap, or kippah, was assaulted by a teenager wielding a machete. The 15-year-old attacker stated in police custody that he felt ashamed that he did not manage to kill his Jewish victim. Like many of the attacks during 2015, this one took place in Marseille, which has France’s second-largest Jewish population. In the days following the attack, Jewish community leaders in France debated whether they should discourage the wearing of kippahs or not. France’s top Jewish community leader, Zvi Ammar, recommended that Jewish men and boys refrain from wearing the skullcap “until better days.” French President Francois Hollande rejected this sentiment, stating that it is “intolerable that in our country citizens should feel so upset and under assault because of their religious choice that they would conclude that they have to hide.”(Daily Mail, January 15, 2016)

Seventy-three-year-old French Jewish politician Alain Ghozland was found dead in his apartment from multiple stab wounds on January 12, 2016. It appeared that his apartment had also been robbed.

On April 4, 2017, 65-year-old Jewish mother Sarah Halimi was assaulted in her third-floor apartment by a 27-year-old neighbor, Kobili Traoré. Traoré gained access to a neighboring apartment and climbed out of their balcony up to Halimi’s apartment. He called her a “demon” and shouted Arabic slogans as he beat her savagely before throwing her out the window to her death. A judge controversially found Halimi unfit to stand trial, citing a “psychotic episode” shortly before the incident. That decision was upheld on appeal.

A memorial to young victims of the Holocaust in Lyon, France, was smashed by vandals in August 2017. French President Emanuel Macron denounced the perpetrators as shameful and cowardly, and local Jewish groups committed to rebuilding the memorial.

In a speech to the CRIF umbrella group of French Jewish communities in December 2017, French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe condemned anti-Semitism, which he said has deep roots in France. “In our country, anti-Semitism is alive. It is not new, it is ancient. It is not superficial; it is well-rooted, and it is alive. And it hides always behind new masks, attempts to justify itself through diverse reasons. This ideology of hate is here, it’s present and it’s making some French Jews to make aliyah.” Pained by the trend, he added, “It should be a spiritual choice, but it pains all citizens of the republic when it’s a form of self-exile, made out of insecurity and fear.”

On August 24, 2024, an explosion outside the Beth Yaacov synagogue in La Grande-Motte, southern France, injured a police officer. The terror attack involved a 33-year-old Algerian man with French residency, who was caught on surveillance footage wearing a Palestinian flag. The explosion was caused by two cars being set ablaze, one of which contained a propane gas tank. Authorities revealed that the suspect had become increasingly radicalized in recent months, harboring deep animosity towards Jews due to the situation in Gaza. He admitted to staging the attack to support the Palestinian cause and to provoke a reaction from Israeli authorities. Prosecutors are pursuing preliminary charges against him, including attempted murder, arson motivated by race or religion, and armed violence against police. French President Emmanuel Macron condemned the attack as an act of antisemitism, and police reinforcements were ordered to protect Jewish places of worship across the country. The Representative Council of Jewish Institutions in France (CRIF) described the incident as an attempt to kill Jews, highlighting the rising antisemitic sentiment in the country since the onset of the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Anti-Zionism Cloaked as Anti-Semitism

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo said during her address at the CRIF event that “anti-Semitism, which cloaks itself as anti-Zionism, must never be allowed to succeed.” She said her city opposes the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement against Israel, whose promotion is illegal in France and is considered incitement to discrimination or racial hate.

In January 2018, two Jewish children were assaulted in separate attacks. In one case, a 15-year-old Jewish girl was slashed in the face while walking home from her private Jewish school wearing its uniform. The second instance involved an 8-year-old Jewish boy wearing a kippah while walking to a tutor who two teenagers beat. After the second attack, French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted, “Every time a citizen is attacked because of his age, his appearance or his religion, the whole country is being attacked.” He added: “And it is the whole country that stands, especially today, alongside the French Jews to fight each of these despicable acts, with them and for them.”

Jewish Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll was murdered in her Paris apartment on March 24, 2018, in what French authorities deemed a religiously-motivated hate crime. The 85-year-old victim had been stabbed to death and badly burned when the attackers tried to set fire to her apartment. Two suspects, Yacine Mihoub and Alex Carrimbacus, were arrested in the days following the attack.

Knoll’s death inspired a rally against anti-Semitism in Paris the following week.

More than two years later, in May 2020, the two men were indicted for murder aggravated by anti-Semitic hatred.

Le Parisien released a statement condemning anti-Semitism signed by over 250 prominent French figures on April 22, 2018. The statement, drafted by a former editor of the Charlie Hebdo magazine, specifically draws connections between France’s Muslim minority population and recent anti-Semitic activity in the country. A group of 30 influential French Imams issued a harsh condemnation of recent anti-Semitism and Islamic terrorism during the same week. In the letter published in the French daily Le Monde, the Muslim leaders derided the confiscation of our religion by criminals.

Approximately 40% of all violent acts in France classified as racially or religiously motivated during 2017 were perpetrated against Jews, and anti-Semitic acts reported in France saw a 20% increase from 2016 to 2017. Anti-Semitic acts rose by 74 percent in 2018, increasing from 311 to 541.

At the beginning of 2019, there was a rash of incidents. In February, for example, a tree was planted in the Paris suburb of Sainte-Genevieve-du-Bois in memory of Ilan Halimi, a young man who, in 2006, was kidnapped and tortured because a gang thought his Jewish family had a lot of money to pay the ransom, was chopped down. Artwork on two Paris post boxes showing the image of Simone Veil, a Holocaust survivor and former magistrate, was defaced with swastikas, while a bagel shop was sprayed with the word “Juden,” German for Jews, in yellow letters. The public was particularly outraged when protestors were filmed hurling abuse on February 16, 2019, at Alain Finkielkraut, a well-known Jewish writer and son of a Holocaust survivor.

Francis Kalifat, president of CRIF, told the Jerusalem Post in October 2021 that “Jewish life in France is flourishing. “We are building synagogues, Jewish community centers, [and] there are a lot of Jewish cultural events in France. Jewish education is doing well, and France is really the center of Jewish life in Europe.”

On the other hand, he said, anti-Jewish hatred from the far Right and the extreme Left, often masked behind anti-Zionism, continues to be a problem. Most concerning, however, are radical Muslims, particularly in low-income neighborhoods with large immigrant populations. Kalifat said 12 French Jews have been killed over the past 15 years by extremist Muslims.

“Anti-Semitism is not the problem of the Jews; it’s the problem of the French Republic at large, and the public authorities must understand that these threats to Jewish life can affect the decision of people living as Jews in France and Europe and needs to be taken into account,” he said.

Reports of anti-Semitic incidents in France increased by 75% in 2021, according to the French Jewish community’s main watchdog group. Incidents targeting people – as opposed to communal buildings and institutions – accounted for 45% of all incidents in 2021. Of those, 10% were physical assaults. Use of weapons, mostly knives and guns, in anti-Semitic incidents was also unusually high in 2021, occurring in 20% of all assaults and 10% of all cases of intimidation, the report said. In nearly a third of all cases, perpetrators indicated they were motivated by issues connected to Palestinians, which is likely due to the violence and protests that followed Israel’s war in Gaza in May (Operation Guardian of the Walls).

The increasingly hostile environment, combined with the economic problems in France, prompted a significant jump in immigration to Israel. Nearly 36,000 French Jews made aliyah to Israel between 2000 and 2015. A record high of 6,628 made the move in 2015, the year of a coordinated terror attack on Paris. An average of 2,829 French Jews fleeing anti-Semitism and terror attacks immigrated to Israel in the following six years. French Jews have also increasingly chosen Britain as their new home. Still, with 446,000 Jewish residents, France remains the Diaspora’s second-largest (after the United States) Jewish community.

In the wake of the Israeli war with Hamas that began with the terrorist massacre of 1,400 Israelis on October 7, 2023, anti-Semitism surged in France. In Paris and other cities, Stars of David were spray-painted on the walls of buildings. In Lyon, a Jewish woman was stabbed, and a swastika scrawled on her door. Overall, anti-Semitic acts increased from 436 in 2022 to 1,676 in 2023, with nearly 60% of those acts being attacks involving physical violence, threatening words, or menacing gestures, according to CRIF. The number of incidents after October 7 “equalled that of the previous three years combined”

French Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne, whose father survived Auschwitz, said, “My government is determined to wage a merciless fight against” anti-Semitism and that “It is the duty of the republic to protect all the Jews of France.”

Interior Ministe.r Gerald Darmaninon ordered local authorities to ban all pro-Palestinian demonstrations and tighten security around Jewish schools, synagogues, and other sites.

According to Macron, 13 French citizens were killed by Hamas; 17 were missing and believed to be among the more than 200 hostages taken by the terrorists.

Concerns about rising antisemitism in France surged on May 17, 2024, when police shot and killed an armed man attempting to set fire to a synagogue in Rouen. The incident, which shocked the city, comes as President Emmanuel Macron addresses increasing antisemitic acts following the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel and the war in Gaza. A recent poll shows 76% of French citizens and 92% of French Jews believe antisemitism is widespread, up significantly from 2022. French universities face challenges distinguishing between criticism of Israel and antisemitism, leading to police clearing pro-Palestinian protesters who made Jewish students feel unsafe. The government is also investigating politicians accused of condoning terrorism. This arson attempt highlights the difficulties in maintaining security. The country’s terrorism alert remains high after various incidents, including the recent killing of a high-school teacher by a man on a terrorism watch list.

A study by CRIF, conducted via Ipsos in September 2024, revealed significant anti-Semitism in France, with 12% of the population and 20% of those under 35 expressing they would welcome Jews leaving the country. Nearly half (46%) of respondents endorsed multiple anti-Semitic stereotypes, including beliefs about Jewish wealth (46%), loyalty to Israel over France (52%), and undue political influence (49%). Anti-Semitic views were more prevalent among far-left La France Insoumise (LFI) supporters than the far-right, with 55% of LFI backers agreeing with such views and 44% not classifying Hamas as a terrorist organization. While 75% held favorable views of Jews, only 21% viewed Israel positively, down from 27% in 2020. Nonetheless, 89% of French citizens rejected any justification for anti-Semitism, offering a glimmer of hope amidst troubling findings.

A March 2025 Institut français d’opinion publique (IFOP) survey commissioned by CRIF reveals a troubling rise in anti-Semitism among French youth, particularly in immigrant Muslim communities. The study, involving over 2,000 minors, highlights widespread religious and identity tensions in schools, with Jewish students disproportionately targeted. The problem is most acute in priority education networks (REP) in immigrant-heavy areas, where 72% of Muslim students oppose friendships or relationships with Jewish peers who support Israel. The findings link increased anti-Semitism to poorly integrated Muslim immigration, especially from former French colonies in North Africa. Despite the severity of the issue, mainstream media and political leaders have largely remained silent, raising concerns about addressing the growing cultural divisions in France.

On March 22, 2025, Rabbi Aryeh Engelberg, the chief rabbi of Orléans, was assaulted while walking home from synagogue with his 9-year-old son. The attacker, a 16-year-old boy with no prior record, punched, kicked, and bit the rabbi on the shoulder, causing injuries to his head and hand. A passerby intervened, prompting the assailant to flee, but he was later arrested. The Orléans public prosecutor has opened an investigation into the attack as a hate crime. Mayor Serge Grouard condemned the incident as “despicable and intolerable,” expressing support for the rabbi and the Jewish community.

Protests Against Anti-Semitism

Political leaders from all parties, including former Presidents Francois Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy, gathered in Paris on February 19, 2019, filling the Place de la Republique, a symbol of the nation, to decry anti-Semitic acts with one common slogan: “Enough!”

Demonstrations were also held in cities from Lille in the north to Toulouse and Marseille in the south.

Earlier in the day, 96 gravestones were vandalized in a Jewish cemetery in the eastern French village of Quatzenheim. President Emmanuel Macron paid respects at one of the desecrated graves and said, “Whoever did this is not worthy of the French republic and will be punished... We’ll take action, we’ll apply the law and we’ll punish them.”

Macron later visited the national Holocaust Memorial in Paris with the heads of the Senate and National Assembly.

One reason for the demonstrations was an increasing number of anti-Semitic incidents by “yellow vest” protesters, so called because of the color of vests worn by people objecting to rising fuel prices, the high cost of living, and claims that a disproportionate burden of the government’s tax reforms was falling on the working and middle classes.

In response to the upsurge of violence, Macron said that France needed to draw “new red lines” against intolerance and announced plans for a bill to combat online hate speech. He also called for the dissolution of three extremist right-wing groups.

The French president said he would also urge his education minister to look at how Jewish children are “too often” forced to leave public schools for private Jewish schools due to racism and harassment. He said France would also take steps to define “anti-Zionism as a modern-day form of anti-Semitism.”

Following an assault in Strasbourg on a Jewish graphic artist on August 27, 2020, the archbishop of the city, Bishop Luc Ravel, condemned the attack and said people needed to speak out against anti-Semitism. “A great concern is born in my heart in the face of the repetition of such acts,” he declared, “and the lack of conscience in those who do not oppose them.” Ravel added, “Their silence supports them, their indifference feeds them.”

Ahmed Moualek, 53, a blogger who posted videos of himself calling for the murder of Gilles William Golnadel and Alain Jakubowitz, two well-known Jewish lawyers, as well as journalist Elisabeth Levy, was found guilty on May 27, 2021, of promoting terrorism and making death threats. He was sentenced to five years in prison by a court in Cusset, France.

In an address to CRIF in February 2022, President Macron said, “The fight against anti-Semitism is European. I said this last January 27 on the occasion of the International Day dedicated to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust. France has chosen to make the fight against racism and anti-Semitism one of its major priorities for its Presidency of the Union. The fight is and remains of course nationally. France, which hosts the largest Jewish community in Europe, must show the way.”

With anti-Semitic incidents increasing dramatically after the start of the Gaza War, an estimated 180,000 people marched in rallies against anti-Semitism on November 12, 2023.

On March 3, 2024, a Jewish man was verbally and physically assaulted as he left a synagogue in Paris. The attack occurred soon after the Interior Minister ordered increased police protection for Jewish communities and institutions around the country.

Relations with Israel

France and Israel have maintained relations since before the state’s founding. Strong contacts between the Yishuv and the Free French existed before the War of Independence; France gave moral and financial support to Palestine’s illegal immigrants. In 1947, France supported the UN partition plan, but normalization between the two countries was gradual.

Cooperation between France and Israel was at its height during the Sinai campaign in 1956 and afterward until the Six-Day War in 1967. During this period, France became one of Israel’s main arms suppliers, and a network of technical and scientific cooperation was established. A cultural agreement was signed between France and Israel in 1959, establishing French language and literature classes at Israeli universities and Hebrew language instruction at French universities.

After De Gaulle came to power in 1958, France began reconsidering its Middle East policy. Franco-Israeli relations deteriorated after the Six-Day War when De Gaulle imposed an arms embargo against Israel and supported the Arab position. France began renewing its relations with Algeria and other Arab states, further distancing itself from Israel. De Gaulle’s resignation in 1969 and his subsequent death in 1972 did not lead to any change in policies toward Israel. President Georges Pompidou endorsed a pro-Arab Middle East policy. After his sudden death in 1974, Alain Poer, a longtime friend of the Jews, took over as acting president. Nevertheless, France continued to become closer to the Arab states and did not intervene in the boycott of Jewish banks by Arab investors.

Francois Mitterrand’s presidential election in May 1981 brought hope of a favorable change in attitude toward Israel. These hopes were reinforced when Mitterrand visited Israel in early 1982. In this visit, Mitterrand expressed the need for a Palestinian state, disappointing those who wanted to see more robust support for Israel.

During the Lebanon War, France tried to pass a UN resolution pressuring Israel into accepting a cease-fire and not entering Beirut; the United States vetoed the UN resolution. Historically, France and Lebanon were close since Lebanon used to be a French colony.

In the 1990s, Mitterrand sent forces to join the Allies during the Gulf War. He also met with President Herzog in 1992 and established Maison France-Israel, located in the heart of France. Despite these positive developments, a questionable friendship with Rene Bousquet, secretary general of the police in the Vichy government, who was assassinated in 1993, embittered many French Jews.

Mitterrand was replaced as president by Jacques Chirac in 1995. Chirac was the first head of state to address the Palestinian legislative council in 1996. He also supports a more prominent European role in the peace process, especially in mediating a peace agreement between Israel and Lebanon. Subsequent leaders have also sought to increase France’s role in the region, particularly in the negotiations between Israel and its neighbors, but the Israeli sense that France and other European countries side with the Palestinians has minimized their influence. Still, recent leaders, including Nicolas Sarkozy and current president François Hollande, have enjoyed good relations with Israel.

Those ties were tested in December 2014, however, when the French Parliament, following the examples set by Ireland, Britain, Spain, and Sweden, voted to recognize “Palestine unilaterally.” The French Parliament released a statement saying it hoped to use the recognition of a Palestinian state as a means of resolving the conflict with Israel.” This vote was condemned by Sarkozy, who referred to the security of Israel as the “fight of his life.” Sarkozy expressed support for a two-state solution and recognition of a Palestinian state eventually, but he told members of his UMP party that “unilateral recognition a few days after a deadly attack and when there is no peace process? No!” Sarkozy was referring to the deadly attack in which two Palestinian cousins, Ghassan, and Uday Abu Jamal, entered the Kehilat Yaakov synagogue in Jerusalem during morning prayers and massacred five individuals with guns, knives, and axes. In response to the vote, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asked, “Do they have nothing better to do at a time of beheadings across the Middle East, including that of a French citizen?” (

Considering these recent votes to recognize a Palestinian state, EU Foreign Policy Chief Federica Mogherini expressed doubts as to whether the movement to unilaterally recognize Palestine is beneficial to the peace process. Mogherini explained that “The recognition of the state and even the negotiations are not a goal in itself, the goal in itself is having a Palestinian state in place and having Israel living next to it.” She encouraged European countries to become actively involved and push for a jump start to the peace process instead of simply recognizing the state of Palestine. Mogherini said that the correct steps to resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict might involve Egypt, Jordan, and other Arab countries forming a regional initiative and putting their differences aside at the negotiation table. She warned her counterparts in the European Union about getting “trapped in the false illusion of us needing to take one side” and stated that the European Union “could not make a worse mistake” than pledging to recognize Palestine without a solid peace process in place.

French officials announced on January 29, 2016, that they would be spearheading an initiative to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and pledged to recognize the independent state of Palestine if their efforts were to fail. French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius revealed preparation plans for an international conference “to preserve and make happen the two-state solution,” including American, European, and Arab partners. The French initiative to convene a global peace summit to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was presented to Israeli diplomats on February 15, 2016. The French initiative included a 3-step process: consulting with the parties involved, convening a meeting in Paris of the international negotiation support group including several countries wanting to jump-start the peace process, and finally, the summit itself that will hopefully re-start negotiations between the Israelis and Palestinians. In contrast to the comments of Palestinian Authority Foreign Minister Riyad al-Maliki, who stated during a February visit to Japan that the Palestinians “will never go back and sit again in direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations,” Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas said that he welcomed the French proposal. The proposal was scoffed at by Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu, who called the initiative “bizarre” and maintained that bilateral negotiations between the Israelis and Palestinians were the only way to achieve lasting peace.

In late 2016, French President Francois Hollande’s presidential plane was upgraded with an Israeli-made defense system. The system, developed by Elbit, uses thermal-imaging cameras to detect incoming missiles or other threats and targets them with a laser beam that disrupts their tracking systems.

The French government announced a second Middle East peace conference in Paris in January 2017, which the Israelis once again soundly rejected. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu verbally assailed the organizers, referring to the conference as a “rigged conference, rigged by the Palestinians with French auspices to adopt additional anti-Israel stances.”

French pilots joined their peers from Israel, the United States, Germany, Italy, India, and Poland in June 2017 for the 2017 Blue Flag exercise, the largest aerial training exercise ever in Israel.

Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu visited France on July 16, 2017, to mark 75 years since the mass deportation of French Jews to concentration camps. In addition to attending a ceremony in commemoration of the mass deportation, Netanyahu and French President Emmanuel Macron held a formal meeting at the Élysée Palace. The visit was a resounding success despite criticisms and protests in the previous weeks.

Although promoting the boycott of Israel is illegal, it was disclosed that the French Development Agency gave an 8 million Euro grant in 2020 to the NGO Development Center. This Palestinian group rejects “any normalization activities with the occupier [Israel], neither at the political-security nor the cultural or developmental levels.”

In an address to CRIF in February 2022, President Macron said, “Like you, I am concerned about the United Nations resolution on Jerusalem which continues to deliberately and against all evidence remove Jewish terminology from the Temple Mount....Erasing Jerusalem’s Jewishness is unacceptable, just as it is unacceptable that in the name of a just fight for freedom, associations misuse historically shameful terms to describe the State of Israel.”

Macron also reacted to a report by Amnesty International accusing Israel of “apartheid.” He said, “How dare we talk about apartheid in a state where Arab citizens are represented in government and positions of leadership and responsibility?”

Following the Hamas massacre of 1,400 Israelis and the taking of more than 200 hostages on October 7, 2023, the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States released a joint statement expressing “steadfast and united support to the State of Israel” and “unequivocal condemnation of Hamas and its appalling acts of terrorism.” On October 22, the leaders of the U.S., Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and the UK issued a joint statement supporting Israel and expressing concern for civilians and hostages.

French President Emmanuel Macron met with Netanyahu on October 24. “We will fight against this terror together, the way we fought against ISIS,” Macron said.

Relations became more testy as the civilian toll in the war in Gaza grew, and Macron became more critical of the Israeli operation.

On May 31, 2024, the French Defense Ministry and the organizers of the Eurosatory arms and defense industry exhibition announced that Israel will not be able to participate in the event. This decision came in response to Israel's continued operations in Rafah, following President Macron’s calls for Israel to cease its operations in the area.

Just days after the July 2024 election French President Macron called Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu to complain of Israeli Diaspora Minister Amichai Chikli interfering by supporting Marine Le Pen's far-right party. Netanyahu promised to prevent further interference, but Chikli continued making statements. An Israeli diplomatic source said Chikli acts independently with far-right European parties, often without the Foreign Ministry’s knowledge.

On October 5, 2024, French President Macron called for an immediate halt to arms deliveries to Israel, emphasizing the need for a political solution to the escalating Gaza conflict since Hamas’s attack on October 7. He reiterated that France is not supplying arms to Israel and that efforts should focus on achieving peace rather than prolonging the conflict. This stance drew criticism from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who deemed the arms embargo call “a disgrace,” highlighting Israel’s need for self-defense against Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran. Following their phone conversation, Macron expressed solidarity with Israel’s fight against terrorism but insisted that continuing arms deliveries would not enhance security for Israel or the region. He has also faced backlash from members of his party, allies, and U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham, who argued that France should “double down on helping Israel because the people who want to destroy Israel also want to destroy the French people.”

On October 15, 2024, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressed his opposition to a unilateral ceasefire in Lebanon during a phone call with French President Emmanuel Macron, emphasizing that Israel’s military actions aim to neutralize the threat from Hezbollah and ensure the safety of northern residents. This conversation followed a report suggesting Macron had criticized Netanyahu, stating that Israel’s establishment was based on a UN decision, while urging adherence to UN resolutions. In response, Netanyahu’s office rebuked Macron’s remarks, referencing France’s World War II collaboration with the Nazis and stating that Israel was founded through its War of Independence.

On October 16, 2024, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant criticized French President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to prohibit Israeli firms from exhibiting at an upcoming naval arms show in Paris, labeling it a “disgrace” and accusing France of maintaining a hostile stance toward the Jewish people. The decision was made despite allowing participation by firms which have known ties with sanctioned Iranian companies, including Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) naval sector. An Israeli source indicated French companies lobbied to exclude Israeli firms for competitive reasons. On October 30, 2024, a French court overturned President Macron’s decision to exclude Israeli companies from the exhibition, a move influenced by legal and diplomatic efforts from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Foreign Minister Israel Katz hailed the ruling as “an important victory for justice and a clear message against attempts to weaken Israel in its fight against the forces of evil.” On November 15, 2024, it was reported that a French government representative responsible for the Paris region has filed an appeal with the Paris Administrative Court to overturn the ruling. Although the Euronaval maritime defense exhibition ended a week before, the appeal’s primary implication is to allow the French government to block Israelis from future defense exhibitions, including the significant Paris Air Show. In response, the Manufacturers Association of Israel vowed to continue their legal fight against what they see as discriminatory attempts to exclude Israeli companies from international exhibitions.

This adds to ongoing tensions stemming from France’s disapproval of Israel’s military actions in Gaza and Lebanon, particularly after failed diplomatic efforts to secure a truce with Hezbollah. Despite France’s claims of commitment to Israel’s security, Macron’s calls for a ceasefire and criticism of Israel’s military operations have further strained relations, prompting sharp responses from Israeli officials who assert their right to defend against multiple fronts, regardless of France’s stance.

In response to the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrants against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant issued on November 21, 2024, France initially stated that its reaction would align with the court’s statutes. The following day, France moderated its position, emphasizing that the ICC’s decision was not a ruling but a formalization of accusations. French Foreign Ministry spokesman Christophe Lemoine reiterated France’s commitment to supporting international justice and respecting the ICC’s independent work under the Rome Statute. On November 27, 2024, France affirmed that Netanyahu has immunity under international law, as Israel is not a party to the ICC statutes. It emphasized that such immunities must be considered if the ICC requests his arrest. France intends to continue working closely with Netanyahu despite the ICC’s recent arrest warrant.

According to a 2024 report by the Counter Extremism Project (CEP), France’s partnership with Qatar carries significant implications for Israel. As Qatar’s investments in France expand into luxury goods, hospitality, and sports sectors, it gains increasing cultural leverage, which has influenced French foreign policy, especially concerning the ongoing conflict in Gaza. Qatar, which provides substantial financial support to Hamas, uniquely influences French affairs and may impact France’s stance in regional disputes. The report also highlights that Macron’s recent foreign policy choices align him with Iran in Lebanon and the Caucasus. His support for Hezbollah-linked political agreements in Lebanon and his arms support for Armenia, opposed by Azerbaijan (an ally of Israel), further reflect this trend. These actions indicate that France’s policy in the Middle East and neighboring regions could challenge Israeli interests amid shifting alliances.

On January 26, 2025, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu secured assurances from French President Emmanuel Macron that Israeli companies would be able to participate in the Paris Air Show in July following a series of disputes. Tensions arose after Netanyahu highlighted France’s 2021 Mali airstrike during a Gaza conflict-related interview, angering Macron and prompting bans on Israeli companies from recent French defense exhibitions. Legal battles led by Israeli advocates overturned these bans, allowing limited participation, but not without significant delays. Israeli firms, including Israel Shipyards and Israel Aerospace Industries, have continued to compete against French defense companies in global markets, securing substantial contracts like Morocco’s $1 billion satellite deal. Israeli participation in the prestigious Paris Air Show is now confirmed despite past frictions.

On March 5, 2025, France, along with the UK and Germany, urged Israel to ensure the “unhindered” delivery of humanitarian aid to Gaza, emphasizing that aid should not be used as a political tool or tied to a ceasefire. They warned that Israel’s recent decision to block aid deliveries until Hamas agrees to terms for extending the truce could violate international humanitarian law. The three European nations described the situation in Gaza as “catastrophic” and called for the immediate and unconditional release of all hostages, alongside the continuation of humanitarian aid. They stressed the importance of maintaining the ceasefire and ensuring the safety and well-being of Gaza’s population.

France supports a one-time release of all hostages held in Gaza as part of a comprehensive deal to end the war. France is actively engaged in diplomatic efforts, working with Arab states to facilitate the agreement. France emphasized the need to transition to a post-war phase focused on ensuring Israel’s security and replacing Hamas rule in Gaza. Macron has previously stressed the importance of a long-term political solution to stabilize the region.

In April 2025, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that France plans to recognize a Palestinian state in the coming months, potentially during a UN conference in New York this June, which France aims to co-chair with Saudi Arabia. Macron emphasized that this move is part of a broader push for mutual recognition between Israel and Palestine, urging pro-Palestinian actors also to recognize Israel’s right to exist. He framed the initiative as a step toward regional stability and a clear stance against actors like Iran who deny Israel’s legitimacy.

Days later, French President Macron reaffirmed France’s stance on Gaza: support for peace, Israel’s security, and a Palestinian state without Hamas. He emphasized the need to release all the hostages, a lasting ceasefire, immediate humanitarian aid, and a political solution based on two states. Macron underscored his support for both the Palestinians’ right to statehood and Israelis’ right to peace and security. He expressed hope that the June conference on the two-state solution would be a turning point.

The same month, a confrontation outside a Jewish-owned bakery in Strasbourg during a pro-Palestinian march sparked widespread condemnation from French politicians, who viewed it as reflective of deeper societal tensions. Though the Dreher bakery itself was not targeted, viral footage showed protesters waving Palestinian flags and clashing with a pro-Israel counter-demonstrator outside the shop, with police intervening. The march, organized by Collectif Strasbourg Palestine, had been planned to pass the location. French officials, including Equality Minister Aurore Berge and Senator Valérie Boyer, decried the incident as emblematic of rising anti-Semitism under the guise of anti-Zionism, calling for urgent national action.

In May 2025, French President Emmanuel Macron warned that France may toughen its stance on Israel and consider sanctions against Israeli settlers if what he described as a “humanitarian blockade” of Gaza continues. Macron said the situation on the ground was “untenable” and urged Israel to change course, reaffirming his support for a two-state solution. In response, Israel’s Foreign Ministry rejected Macron’s claim, calling it a “blatant lie” and insisting there is no blockade. The ministry highlighted ongoing efforts to deliver aid, including nearly 900 trucks and the newly established Gaza Humanitarian Fund, which has distributed millions of meals to date. Israel accused Macron of siding with Hamas and undermining its efforts to defeat terrorism.

The following month, at the Paris Airshow, France shut down the main stands of four major Israeli defense companies, Elbit Systems, Rafael, IAI, and Uvision, for refusing to remove offensive weapons from display, prompting a sharp protest from Israel. While smaller Israeli exhibits without hardware and an Israeli Ministry of Defense stand remained open, Israel condemned the move as an “outrageous and unprecedented decision” motivated by political and commercial interests. France stated that exhibitors had been informed in advance that attack weapons were prohibited, citing its growing diplomatic concerns over Israel’s military actions, particularly in Gaza.

In July 2025, France’s National Court of Asylum (CNDA) ruled that residents of the Gaza Strip can be granted refugee status due to “persecution by the Israeli armed forces.” The landmark decision was made under the 1951 Geneva Convention and applies to Gazans not protected by the UN, citing indiscriminate violence by Israel following the collapse of the January 2025 ceasefire. The case that triggered the ruling involved a Gazan mother and her son, who were admitted to France via consular passes and initially granted temporary protection. The court ultimately recognized them as refugees on the grounds of their Palestinian “nationality,” despite France not formally recognizing a Palestinian state.

Later that month, Reaffirming France’s support for a just and lasting peace in the Middle East, French President Emanuel Macron announced that France would recognize the “State of Palestine,” with a formal declaration planned for the UN General Assembly in September. Emphasizing the urgency of ending the war in Gaza, he called for an immediate ceasefire, the release of all hostages, and massive humanitarian aid, alongside the demilitarization of Hamas and the rebuilding of Gaza. He stressed that the creation of a viable, demilitarized Palestinian state that recognizes Israel is essential to regional security, and pledged France’s commitment to making peace a reality.