Warsaw, Poland

Warsaw, the capital of Poland,

once had a Jewish population equivalent to the number of Jews living

in all of France. It was the only city that rivaled New York’s

Jewish population. The city's Jewish population was decimated during the Holocaust. Today only fragments remain.

- Early History

- Religious, Social & Political Life

- Jewish Press

- World War I & Inter-War Period

- The Holocaust

- Deportations

- Ghetto Uprising

- Post-War Warsaw

- Present-Day Community

- Jewish Tourist Sites

Early History

Jews settled in Warsaw during the 14th century, after the reign of King Kasimierz. Even at this early stage,

non-Jewish townsman felt hostility toward the Jews. In 1483, Jewish

inhabitants were expelled from Warsaw. From 1527-1768, Jews were

officially banned from the city; consequently, Jewish settlers lived

in jurydykas (privately owned settlements) on the outskirts of

the city.

|

Some

Jews were allowed to enter the city for short periods of time. After

1572, Jews were allowed to enter Warsaw during conventions of the

National Sejm (parliament). Jewish representatives in the Council of

Lands were also permitted to visit Warsaw. According to a census in

1765, 2,519 Jews lived in Warsaw. This number increased after Jews

were officially allowed to live in the city in 1768. By 1792, the

Jewish population nearly tripled to 6,750. A Jewish bourgeoisie began

to form in Poland, consisting mainly of businessman, taverners, and

artisans. Jewish entrepreneurs also emerged, acting as moneylenders

and army suppliers.

Jews were not allowed to have an authorized Jewish

community until the Prussian conquest; however, those living in the

city still ran prayer meetings, charitable associations and appointed

Jewish leaders to take care of tax collection and other judicial

services.

Following the first partition of Poland in 1772, a

rise in organized street fights against the Jews took place. Three

years later, there was a partial expulsion of Jews from Warsaw.

Many Jews in Warsaw participated in the Polish

uprising against the Russians during the partition period and were

killed when Russian troops massacred the Jewish civilian population.

In 1796, Warsaw became part of Prussia and Jews

were subject to Juden Reglements, which only allowed Jews living in

Warsaw prior to 1796 to remain in the city. By 1804, 11,630 Jews

lived in Warsaw. Jews were subject to attacks by the Polish

population in 1805.

In the late 18th century, Hasidism spread to Warsaw. On the other hand, the Haskalah,

Jewish enlightenment, was not as strong. The followers of the

Enlightenment Movement (maskilim), led by Isaac Flatau, formed

their own synagogue, called the

German Synagogue, in 1802.

In 1809, a Jewish quarter was established in the

city. Only Jewish bankers, merchants, manufacturers, army suppliers,

and doctors were allowed to live there, if they agreed to wear

European style clothing and send their children to general schools.

In 1826, a government-sponsored Rabbinical

assembly opened; it closed in 1863 during the Polish uprisings.

The population of Warsaw continued to grow in

the19th and 20th century. In 1816, Jews numbered 15, 600

and, by 1910, the population reached 337,000 (38% of the total

population of Warsaw). This rise was due to mass migration in the

1860's and another set of migrations after the 1881 pogroms in

Russia, after which 150,000 Jews moved to Warsaw. Many Jews came from

Lithuania, Belorussia and the Ukraine.

In the early 1800's, life in the "Jewish

Quarter" was restricted, but improved in the 1860's. Jews

participated in the Polish uprisings against the Russians in the

1860's. Also during this period, Jews continued to play an important

role in banking. Jewish bankers also had monopolies in the sale of

salt and alcoholic beverages. Jews consisted of more than half of all

those involved in commerce in the city and were also involved in the

crafts.

Religious, Social & Political Life

During the late 1800's, Hasidism further spread

throughout Warsaw. Nearly two-thirds of Warsaw’s 300 approved synagogues

were Hasidic. On the other hand, the rise of the Mitnaggdim also grew

with the arrival of the Litvaks. Warsaw’s Jewish leadership, until

the end of the 1860's, was mainly Orthodox.

Four rabbis served all of Warsaw and they removed from office all the

Mitnaggdim, whom did not find favor in the eyes of the Hasidic Jews.

Jewish education in this period was run by Orthodox

groups in the form of the heder, small classes often located

in the house of the rabbi. By the mid-19th century, nearly 90% of all

Jewish children attended heder. In 1896, 433 authorized hederim existed in Warsaw, as well as a number of unauthorized ones.

In this period, assimilationist philosophy became popular

among the youth. Many Jews converted to Christianity and Warsaw had

the highest conversion rate in Eastern Europe.

From

the late 18th century, the Jewish community in Praga was centered around

Szeroka and Petersburska streets (now Jagiellonska and Klopotowska).

A round, masonry synagogue was built in the neighborhood by architect

Józef Lessel in 1836. It was one of only six circular buildings

in all of Europe, and the most important meeting place for Jews in Praga

before World War II.. The

synagogue was used as a delousing center during the Nazi occupation.

After the war, the building housed offices of the Central Jewish Committee

in Poland. In 1961, the building was demolished over Jewish protest,

though it was still in good condition. Since 1991, the site has been

used for a public high school.

The largest and most beautiful synagogue in Warsaw

was the Great Synagogue in Tlomackie Square. This was the only place

offering a Reform service, and it was used by the wealthy and middle

class, as well as the intelligentsia. Unlike the Nozyk Synagogue where Yiddish was spoken, Polish

was used in the Great Synagogue. The synagogue, designed by Leandro

Marconi (who came from a family of architects, one of whom had designed

the Pawiak prison later used in the Warsaw

Ghetto), held 2,400 people and had a large hall, meeting rooms,

an archive, a library, and a school. It was completed in 1878. The Main

Judaic library was erected next to the Great Synagogue in 1936. Construction

was funded by donations of the Jewish population, and State and municipal

subsidies. Its designer was the architect Edward Eber.

|

Most

of Warsaw's synagogues were small, often private, prayer houses located

in the courtyards or backyards of tenements. One such synagogue was

discovered in one of the oldest houses in Praga-Warsaw. Built in 1811

at what is now 50/52 Targowa Street, the building was turned into a

warehouse after World War II. Inside fragments of wall paintings depicting

the Western Wall, Rachel's

Tomb, and signs of the Zodiac remain. A Hebrew inscription says

the paintings were financed by donations in 1934.

Zionist groups flourished

in Warsaw in the late 1800's. Chapters of Hovevei

Zion and the Society Menuha ve Nahalah opened. Hovevei Zion opened

its own modern heder in Warsaw in 1885.

The Bund, Jewish socialists, also promoted their ideologies.

The Bund was popular among Jewish workers and helped promote Yiddish

culture. The Bund was ardently opposed to Zionism and the revival of

Hebrew.

Jewish Press

Yiddish and Polish weeklies emerged in the 1820's

and the Hebrew Press began later in the 1880's. Warsaw became the

center of Hebrew publishing in Poland and many famous writers either

lived or worked in the city, including: Isaac

Bashevis Singer, Shalom Asch, I.L. Peretz, David Frischman and Nachum

Sokolow.

World War I & Inter-War Period

During World War I, thousands of refugees came to

Warsaw. By 1917, there were 343,000 Jews living in Warsaw, about 41%

of the total population. In this period, the Jewish population

increased, while the percentage of Jews living in Warsaw, compared to

non-Jews, decreased to about 30%. Many Jews — about 34% in 1931 —

were unemployed.

The main political struggle in Warsaw and in

Poland took place between the Zionists parties and the Orthodox -Hasidic groups, which had joined together

and formed the Agudat Israel.

By 1936, though, the Bund had received the majority of votes to serve

on the communal leadership and represent the Jewish community in the

Warsaw municipality. The Polish government annulled the election

results, however, and appointed a different community (kahal)

board, which was used until the beginning of the German occupation.

In the inter-war period, a Jewish school system

existed, but most Jews attended state schools. During this period,

many Hebrew writers immigrated to Israel; nevertheless, the Yiddish

and Polish Jewish press still thrived. By the start of World War II,

more than 1,000 Jewish workers were involved in Hebrew printing works

in Warsaw.

The Holocaust

Warsaw’s

pre-war Jewish population in 1939 was 393,950 Jews, approximately one-third

of the city total. From October 1939 to January 1940, Germans enacted

anti-Jewish measures, including forced labor, the wearing of a Jewish

star and a prohibition against riding on public transportation.

In

April 1940, construction of the ghetto walls began. On Yom Kippur, October

12, 1940, the Nazis announced the building of Jewish residential quarters.

Roughly 30% of the city’s population was to be confined to an area

that comprised just 2.4% of city lands. Jews from Warsaw and those deported

from other places throughout Western Europe were ordered to move into

the ghetto, while 113,000 Christians were moved out of the area. The

ghetto was divided into two sections, a small ghetto at the south end

and a larger one at the north end. German and Polish police guarded

its outside entrance and a Jewish militia was formed to police the inside.

The

population of the ghetto reached more than half a million people.

Unemployment was a major problem in the ghetto. Illegal workshops

were created to manufacture goods to be sold illegally on the outside

and raw goods were smuggled in. Children became couriers and

smugglers.

Hospitals,

public soup kitchens, orphanages, refugee centers and recreation facilities

were formed, as well as a school system. Some schools were illegal and

operated under the guise of a soup kitchen. Still, many Jews died from

mass epidemics (such as typhoid) and hunger. The streets were filled

with corpses. Jews in the ghetto still had to pay for burial, and if

they couldn't afford it, the bodies were left unburied.

Clandestine

prayer groups and yeshivot were also started. Some religious Jews believed

that their suffering was preordained and would bring about the Messiah.

There were also many religious Jews involved in heroic acts. One famous

leader was Janusz Korczak,

the director of the Jewish orphanage, who chose to accompany the children

he cared for when they were deported.

Deportations

This first mass deportation of 300,000 Jews to Treblinka began in the summer of 1942. The number of deportees averaged about

5,000-7,000 people daily, and reached a high of 13,000. At first, ghetto

factory workers, Jewish police, Judenrat members, hospital workers and their families were spared, but they were

also periodically subject to deportation. Only 35,000 were allowed to

remain in the ghetto at one time. Adam

Czerniakow, the head of the Warsaw Judenrat committed suicide on July 23, 1942, to protest the killing of Jewish

children.

A second wave of deportations to Treblinka began on January 18, 1943, during which many factory workers and

hospital personnel were taken. Unexpected Jewish armed resistance,

however, forced the Nazis to retreat from the ghetto after four days

of deportations.

Mordechai

Anielewicz

Mordechai

Anielewicz |

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Following

the armed resistance in January 1943, all social institutions and the Judenrat ceased to

function and even walking on the streets became illegal. Mordechai

Anielewicz, at the age of 24, became the leader of the Jewish

Fighting Organization (ZOB). He recruited more than 750 fighters, but

amassed only 9 rifles, 59 pistols and a couple of grenades. A

developed network of bunkers and fortifications were formed. The

Jewish fighters also received support from the Polish Underground.

On

April 19, 1943, the Warsaw Ghetto

uprising began when German troops penetrated the ghetto to begin

a third round of mass deportations. The ZOB faced a formidable force

of 2,000 armed German soldiers, yet the Germans were unable to defeat

the Jews in open street combat. After several days, the Germans switched

tactics and began burning down houses. The ZOB headquarters on 18 Mila

Street fell on May 8, 1943; at this time Mordechai

Anielewicz died in battle.

A Polish partisan fighter from the "Piesc" Battalion of the Armia Krajowa, led by Stanislaw Jankowski "Agaton", on a rooftop overlooking the Ewangelicki cemetery in the Wola district of Warsaw (August 2, 1944). A Polish partisan fighter from the "Piesc" Battalion of the Armia Krajowa, led by Stanislaw Jankowski "Agaton", on a rooftop overlooking the Ewangelicki cemetery in the Wola district of Warsaw (August 2, 1944).

|

On

May 16, 1943, the ghetto was liquidated and the Germans blew up the

Great Synagogue on Tomlacke Street in victory. Sixty thousand Jews

died in the ghetto uprising.

Not all Jews were found by the Nazis by May 16 and

intermittent fighting lasted until June 1943. About 50 ghetto

fighters were saved by the Polish "People’s Guard" and

formed their own partisan group, named after Anielewicz.

The Warsaw Ghetto uprising empowered Jews throughout Poland and

resulted in armed resistance in other ghettos. After the ghetto was

liquidated, Jewish leaders continued to work underground on the

"Aryan" side by hiding Jews and issuing forged documents.

Many Jews became active in the Polish underground of Greater Warsaw.

Post-War Warsaw

In September 1944, Warsaw’s eastern suburb, Praga,

was liberated and, in January 1945, the main parts of the city on the

left bank were liberated by the Soviets. About 6,000 Jews participated

in the battle for the liberation of Warsaw. Two thousand Jewish survivors

were found in underground hideouts, when the city was liberated. When

the city stadium was built, the bones of approximately 100,000 people

were found in a mass grave and reburied in the city cemetery.

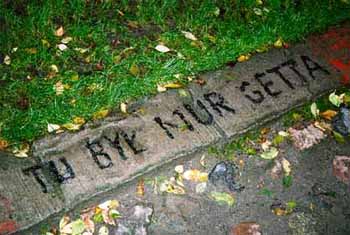

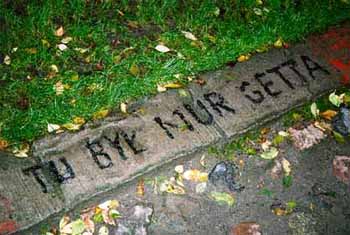

The message reads: "Here was the walls of the Ghetto"

The message reads: "Here was the walls of the Ghetto" |

By the end of 1945, 5,000 Jews settled in Warsaw.

The population doubled when Jews who survived the war in Russia

returned to Warsaw. The city became the seat of the Central Committee

of Polish Jews and a number of Jewish cultural institutions were

opened in 1949.

Over the next two decades, waves of immigration

were stimulated by anti-Semitism and communist persecution. The first

large group left for Israel in 1946-47 following the Kielce

pogrom. Others left in 1957-58 and 1967-68. By 1968, most Jewish

institutions ceased to function.

Present-Day Community

Currently, most of Poland’s Jewish population lives

in Warsaw. The Union of Religious Congregations has its main office

in Warsaw. There is both a Jewish primary school and a kindergarten.

Warsaw also houses the offices of the Main Judaic Library and Museum

of Jewish Martyrology. It is the home also of the E.R. Kaminska Jewish

Theater, the only regularly functioning Yiddish theater in the world.

Most of its actors today are not Jewish. While parts of Europe have

seen an upsurge of anti-Semitism,

this has not occurred in Poland.

While Jews living in Warsaw feel their situation today

is good, few are in prominent positions. One of the major issues for

the community remains the restitution of property taken from Jews during

the war.

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin joined Polish officials, Holocaust survivors, and media representatives on October 28 2014 for the opening of Poland's new "Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews". The building was innaugurated last year and the museum cost in total over $100 million. The museum was built on the grounds where the Warsaw Ghetto stood during the Holocaust. The visit to the opening of the museum was Israeli President Rivlin's first foreign trip since his election in Summer 2014. The core exhibit tells the story of the 1,000 year history of Jews in Poland through 8 chronological gallery sections.

Jewish Tourist Sites

Not one house in the Warsaw Ghetto survived. Everything

was rebuilt after the war, and the area is now a residential neighborhood.

Several monuments to the ghetto and uprising are scattered about the

area.

The Bunker on 18 Mila Street

More

than 100 people died on May 8, when the Nazis surrounded the bunker.

Nothing remains from the bunker. It is marked by a commemorative

stone engraved in Polish, Yiddish and Hebrew

The Musuem of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw

In April 2013, the Museum of the History of Polish Jewry in Warsaw - built on hallowed ground of the Warsaw Ghetto - opened to visitors interested in learning more about the Jewish community of the city. The museum itself is housed in a structure of green glass and stone, symbolic of transparency, and the main entrance faces a plaza dominated by the Nathan Rapoport memorial, which commemorates the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The museum's design was completed by Finnish architects Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma who were chosen from among 200 submissions to Poland’s first international architectural competition. The plot of land for the museum and an additional $13 million were donated by the city of Warsaw to the project.

Chief Curator of the Warsaw Museum and New York University Professor Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett said that the 1,000-year history of Polish Jews, 3 million of whom were killed during the Holocaust, was an “integral part” of the Poland’s history in general. “Jews are not a footnote to Polish history,” Kirshenblatt-Gimblett said.

Memorial of the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto

Between Karmelicka and Zamenhofa streets stands the "Ghetto Heroes Monument". Designed by sculptor Nathan Rappaport. It commemorates all who lost their lives in the Ghetto Uprising led by Mordechai Anielewicz.

Commemorative Gateway.

A

commemorative Gateway Monument was built on the site of the ramp,

known as Umschlagplatz (collection point), used for railroad

transport to Treblinka.

Names of 400 Jews are etched on it. The train station began its first

actions in the summer of 1942.

Warsaw Ghetto Walls

Only

a small piece remains of the ghetto walls, which were about 11 miles

long.

Nozyk Synagogue

The

synagogue was founded in 1902, by Zalman Nozyk, a wealthy Jewish merchant.

The synagogue was known for its singing and religious music and attracts

visitors from around the world. Built by an unknown acrhitect in neo-Roman

style with elements of Byzantine and Mauritian ornamentation, the Nozyk

is Warsaw’s only surviving synagogue from before the war. During

WWII, it was was located in the ghetto. The Germans allowed public worship

in autumn 1941, but it was later used as a stable.

The Warsaw "geniza," a collection of holy

scripts from all over Poland was under the synagogue, but it was nearly

useless for some time because all the people were gone. At one point,

there were more Jewish books in Poland than Jews.

The synagogue was renovated and reconstructed between

1977-83. Today, services are held daily and on major Jewish holidays.

Jewish Historical Institute (ZIH)

In 1993, the Bank Tower was completed on the grounds

where the Great Synagogue once stood. Superstitious residents believe

the site to have been cursed by the last rabbi. Behind the tower is

the Judaic Library building, which suffered major damage during the

war, but was restored and handed over to the Jewish Historical Institute

in Poland. The building presently houses offices and research rooms,

and boasts a large collection of Jewish art, religious objects, and

mementos. Its archives contain a large collection of materials and documents

relating to Jewish history in Poland, including Dr. Emanuel Ringelblum's

Underground Archives. The Institute's library has about 60,000 volumes.

The Jewish Historical Institute in Poland is funded by the State and

acts under the auspices of the Polish Academy of Sciences. The Institute’s

library has more than 60,000 volumes of literature and old manuscripts,

from as early as the 10th century.

Cemeteries

The Brodno Jewish Cemetery

Founded in 1799, it is the oldest Jewish cemetery in

Warsaw. It was almost completely destroyed in the war. In 1985, renovations

took place. One can find a 26-foot sculpture to remember Jewish martyrs.

Okopower St. Jewish Cemetery (Gensha Cemetery)

Dated to the beginning of the 19th century,

it is Warsaw’s largest Jewish cemetery with 250,000 people buried

in 200,000 graves. Special gravestones exist for the Kohanim (priests). Mass graves for 300 victims of the Nazis can be found, as

well as gravestones for those who perished in the Warsaw ghetto and

Jewish officers and enlisted men in the Polish army who lost their lives

defending Warsaw in 1939. Some of the more famous gravestones include,

I.L. Peretz (writer), Meir Balaban (historian), Esther Kaminska (actress)

and Dr. Zaminhoff (the creator of Esperanto). There is also a statue

commemorating Janusz Korczak.

Ordinarily, a Jew who commits suicide is not allowed to be buried in

a cemetery, but the family of Adam

Czerniakow, the head of the Warsaw Judenrat who killed himself during the war to protest the killing of Jewish children,

was given special dispensation for burial in the cemetery.

Sources: Beyond

the Pale: The History of Jews in Russia.

Gruber, Ruth Ellen. Jewish

Heritage Travel: A Guide to East-Central Europe. Jason Aronson,

Inc. Northvale, New Jersey, 1999.

"Newly Opened Museum Aims to Show Jews Not a 'Footnote to Polish History'," E-Jewish Philanthropy (April 17, 2013).

Johnson, Paul. A

History of the Jews. Harper & Row, Publishers. New York.

1987.

LNT

Poland

March of

the Living - Canada

Poland. Encyclopedia

Judaica. CD-ROM Edition. Judaica Multimedia. 1995.

Poland. Virtual Jerusalem - Jewish

Communities of the World

Polish-Jewish

Relations

Grange

Ghetto

Photo Credits: Holocaust photos courtesy of Andrew

Kobos' Shoah

- The Holocaust site. Cemetery photo courtesy of Pawel Brunon Dorman. Warsaw underground fighter photo from Wikimedia Commons. Peretz grave photo courtesy of Stephen

Epstein/Big Dipper Communications. Warsaw tower, old city, memorials,

ghetto wall photos courtesy of Scrap

Book Pages. |