|

[By: David Shyovitz]

The Jewish presence in the Netherlands [Holland] began, and nearly ended, in tragedy: The first Jews came after being expelled

from Spain, and the huge community was decimated 350 years later

by the Holocaust. In between, Dutch

Jews contributed to one of the most

prosperous and enlightened eras in the history of the Netherlands. The

history of Jews in the Netherlands was different than their experience

in any other country. There was a concerted effort by Jewish leaders during the Holocaust to perserve Dutch Judaism, which was still decimated by deportations. Today, the Jewish community of the Netherlands numbers approximately 29,900.

- Early History

- New Beginnings

- Jews in the "Golden Age"

- Emancipation Debate

- Holocaust Era

- Modern Period

Early History

It is likely that the earliest Jews arrived in the

“Low Countries,” present day Belgium and the Netherlands, during the Roman conquest early in the common era. Little is known about these early

settlers, other than the fact that they were not very numerous. For

some time, the Jewish presence consisted of, at most, small isolated

communities and scattered families. Reliable documentary evidence dates

only from the 1100s; for several centuries, the record reflects that

the Jews were persecuted and expelled on a regular basis. The most violent

such persecution took place in 1349 and 1350, after the Jews were accused

of spreading the Black Plague. Rioters massacred the majority of the

Jews in the region and expelled those who survived. For the next two

hundred years, the number of Jews in the area was likely close to zero.

By the time the Dutch principalities rebelled against Spain late in the sixteenth century to form the United Provinces of the Netherlands,

there were probably no Jews left.

Interestingly, while the Jews were numerically inconsequential

in the region during medieval times, their place in the Low Countries'

culture was much more prominent. A significant portion of the surviving

literature and poetry from that era is rife with anti-Semitic references, and the contemporary Christian legends emphasize the perfidy

of the Jews, and their role in the death

of Jesus.

News Beginnings

Beginning in the sixteenth century, the Netherlands

became home to numerous Portugese merchants, as the region, and particularly

the city of Amsterdam, became a center of world trade and shipping.

Among these merchants were many Marranos, who had been forced out of Spain by the Inquisition in 1492. They kept their Jewish identities a secret, but, by the end

of the century, had formed a community in Amsterdam, a city that did

not recognize religions other than Protestantism. The community was

discovered, and its leaders arrested, in 1603. As a result, some of

the newly-acknowledged Jews moved to the towns of Alkmaar, Rotterdam,

and Haarlem, which extended them protective charters. The majority,

however, remained in Amsterdam, and even founded a second community

there in 1608.

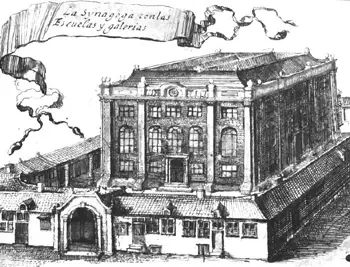

A drawing of the “Snoga”

Sephardi synagogue.

A drawing of the “Snoga”

Sephardi synagogue. |

The Protestant Church, the official religion of the state, was furious

that the Jews were not being repressed, but secular authorities were

not eager to punish the Jews, who had become important traders and merchants.

To clear up the religious controversy, new statutes regarding religious

tolerance were issued in 1619. These new laws left the decisions regarding

Jews completely in the hands of individual city rulers. Amsterdam itself

declared that Jews were welcome, but not as citizens; they could practice

freely, but were somewhat limited in their commercial and political

rights. Most cities followed Amsterdam's example, though some cities

granted Jews complete rights, and others prohibited Jewish settlement

altogether. Thus, the overall status of Jews in the Netherlands remained

inconsistent, but was generally in the Jews' favor.

In 1620, the first Ashkenazi Jews arrived in Amsterdam, and they formed a community by 1635. The

Ashkenazim, who first came from Germany,

and later from eastern Europe as well,

also settled elsewhere in the Netherlands, particularly Rotterdam and

the Hague. The Ashkenazim in the Netherlands soon became superior to

the Sephardim in numbers,

but, with the exception of a few wealthy Ashkenazi families, they remained

inferior socially and economically.

Politically, the Jews were for the most part left

to their own devices. Their internal affairs were managed by the kehilla,

the Jews' semi-autonomous governing body. The Jews judged themselves

in bet dins (religious courts), organized their own educational

system, and appointed leaders from within their own ranks. This political

isolation from the rest of society on the part of the Jews was typical

in Europe in this period.

Jews in the "Golden Age"

In other ways, however, the Netherlands' Jewish community

was atypical. While in general, European Jews isolated themselves economically

and socially as well as politically, the Jews of the Netherlands enjoyed,

as early as the seventeenth century, economic and social integration

that the rest of European Jewry would not know for hundreds of years.

Professions like medicine became very popular, and Jewish physicians

were free to practice even among non-Jews. More importantly, the Jews,

particularly the Sephardim, played a large role in the economic expansion

that elevated the Netherlands to a world center in the 1600s. The Portugese

Jews, with their knowledge of languages and connections to the international

trade network of Jews and Marranos, became important in the shipping

and trading industries. Several Jews were important shareholders in

the East Indies Company, which dominated international trade during

the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Jews became prominent in other

businesses as well, succeeding in the tobacco, sugar refining, and printing

industries. Most of all, the diamond industry soon became an almost

exclusively Jewish occupation due to their success in it.

Because of their economic integration, Jews in the

Netherlands eventually united with the greater society to a much larger

extent than any other Jewish community in this period. While they continued

to be governed by the kehilla, they lived not in a ghetto, but in a

Jewish quarter, which the Jews were free to leave and which was frequented

by non-Jews – the artist Rembrandt, for example, lived and worked

in the Jewish quarter. The anti-Semitic violence that was still prevalent

in Germany and eastern Europe was non-existent in the Netherlands. Christian conversions to Judaism,

while not common, were not unheard of, and secular scholars were remarkably

knowledgeable about Judaism –

at a time when most of Europe believed in the blood

libel that the Talmud required the blood of a Christian child to be baked into matzah, scholars

in Amsterdam were studying the Mishna and the Talmud,

and even composing poetry in Hebrew.

Reciprocally, some Jewish artists and authors made significant contributions

to the flourishing culture of the Dutch Golden Age.

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza |

This account of the Jews' welfare and integration,

however, is subject to a caveat: It was only the Sephardic Jews who were succeeding so well in the Netherlands. The more numerous Ashkenazim were closer

to a proletariat than a merchant class. They continued to speak primarily Yiddish, made no lasting

contributions to Dutch culture, and, more surprisingly, made few contributions

to their own. While many important rabbinical works were published in

the Netherlands because of the excellent printing industry, few, if

any, were composed there. The Ashkenazi community never produced its own rabbis,

and was forced to import them from abroad. Nonetheless, Ashkenazim in the Netherlands did face less persecution than their brethren in

the rest of Europe, and were definitely better off in that regard.

While the relations between Jews and society were favorable

in this period, the internal life of the Jews was far from perfect.

Religious divisions led to several schisms that split the often polarized

community. The most apparent division was that between the Jews of different

nationalities: The Sephardim,

the Jews of Portugese origins,

maintained a kehilla separate from that of the Ashkenazim. The

Ashkenazim themselves were split into two kehillas, a German one and a Polish one, until

1673, when the municipal authority ordered them joined. Further tension

resulted from the messianic frenzy that greeted the announcement, in

1665, that Shabbetai Zvi was

the messiah, and the subsequent

dismay when he converted to Islam.

Within both the Ahkenazi and Sephardi communities of Amsterdam, factions

loyal to the false messiah battled with those who denounced him as a

heretic. In 1713, the ongoing feud resulted in the dismissal of Chief

Rabbi Zvi Ashkenazi; by that point, of course, Shabbetai Zvi was long

dead.

Finally, religious controversy engulfed Amsterdam

communities when an increasing number of apostates appeared on the scene.

Philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who made important contributions to the Netherlands' culture and scholarship,

was excommunicated by all of the leaders of the Amsterdam communities.

Uriel da Costa, another famous heretic of the era, was banned as well.

On a smaller scale, in 1618, the Sephardi community split over how liberal their community should be, and a group

of strictly Orthodox Jews

left the kehilla to begin their own. By 1639, however, that rift

had been mended.

Emancipation Debate

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Netherlands was

in a serious decline. As England and France began to catch up

to and then surpass the Dutch efforts in trade and shipping, the prosperity

that the Netherlands had enjoyed was replaced by economic instability.

At the same time, the Enlightenment moved the focus of European culture

and scholarship from the Netherlands to France.

Matters grew even worse during the Anglo-Dutch war of 1780-1784, and

the subsequent popular revolt that resulted in French occupation of

the Netherlands – trade dwindled to near zero, and a full-fledged

economic crisis affected Jews and non-Jews alike. Consequently, the

gap between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews steadily

narrowed. By the end of the eighteenth century, 54% of the Jewish population

survived only on charity, a figure that was roughly the same in both

Jewish ethnic groups.

Dissatisfied with their economic situation, and influenced

by the nearby French revolution, Jews began to lobby for emancipation,

and the abolition of the autonomous kehilla. The Batavian Republic,

France's puppet government in the Netherlands, officially instituted

emancipation on September 2, 1796, but the rights granted to the Jews

were rebuffed by a large percentage of the community, who wanted to

retain their political separateness. The kehilla split into two

factions: One wanted to be emancipated, the other refused. The government

sided with the pro-emancipation camp, and so did Napoleon Bonaparte,

after he annexed the Netherlands and turned it into the Kingdom of Holland.

Members of a Labor Zionist organization

prepare for immigration to a kibbutz in Palestine.

Members of a Labor Zionist organization

prepare for immigration to a kibbutz in Palestine. |

Despite the technical emancipation, there was no actual

change in the situation of the Jews for some time due to the turmoil

that was affecting the region as a whole. Napoleon's wars and his eventual

defeat made the Netherlands' bad economic situation worse. When, in

1814, a coup again changed the political landscape of the country, the

ruler of the new Kingdom of the Netherlands inherited a Jewish population

composed of nearly 60% paupers. For the first time, the Sephardim were

even worse-off than the Ashkenazim. But improvements were not long in

coming now that the Netherlands was once again an independent country.

An economic boom benefitted the Jews, who became active in the cotton

industry, and returned to the diamond industry. As their prosperity

grew, so too did their rights. King William I began to regulate the

Jewish community's internal affairs, effectively disbanding the Netherlands kehilla; he instituted compulsory secular education for Jewish

children; and he waged a determined battle against Yiddish,

which resulted in the Jews' widespread adoption of Dutch. The efforts

of the government were aided by those of the Dutch maskilim,

who were of course in favor of integration. Soon, Jews infiltrated the

professional classes, and many became doctors and lawyers.

The new opportunities for Jews were most available

in the cities, resulting in the consolidation of nearly all of the Netherlands'

Jews in urban locations by the end of the nineteenth century. Not surprisingly,

the integration into secular society impacted the religiosity of Dutch

Jewry. Orthodoxy lost its influence to Liberalism, and the Jewish population

gradually declined, due to conversions, intermarriage, and a low birthrate.

As a result, the Jewish nationalist movement never got a foothold in

the region, and Zionism never achieved the popularity that it did elsewhere in Europe.

The Holocaust Era

From 1939-1940, 34,000 refugees entered the Netherlands

as Jews fled Nazi Germany. The Netherlands maintained an open-door policy

for immigration. In 1940, at the time of its occupation by the German,

140,000 Jews lived in Holland. Jews represented 1.6 percent of the total

population. This figure includes refugees from Germany, Austria, and

the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

A sign reading “Jewish quarter”

in German and “Jewish neighborhood” in Dutch.

A sign reading “Jewish quarter”

in German and “Jewish neighborhood” in Dutch. |

These refugees would be no better off in the Netherlands.

Soon after the Nazi occupation,

the first anti-Jewish laws removed Jews from their professions, their

schools, and their homes. In late 1941, a deportation plan was intacted

providing for the removal of the Jews from all the provinces and their

concentration in Amsterdam. This phase was launched on January 14, 1942,

beginning with the town of Zaandam. The Dutch nationals among the Jews

were ordered to move to Amsterdam, while those who were stateless were

sent to the Westerbork camp.

The attempt to make Holland Judenrein (clean

of Jews) was completed when the Nazis began to deport Jews countrywide

on October 2, 1942. 12,296 were deported. In May 1943, the rate of deportations

was accelerated. Most were sent to Auschwitz and Sobibor. Interestingly,

a relatively large percentage of the Holocaust survivors in Amsterdam did so by either hiding with non-Jews, or

forging documents with the help of non-Jews. The most famous example

of this phenomenon was the Frank family, who survived for several years

hidden in an Amsterdam building. The diary kept by Anne

Frank has become the most widely-read account of life during the

Holocaust.

In April 2005, Holland’s prime minister Jan Peter

Balkenende, apologized for his country’s collaboration with the

Nazis. The Dutch wartime government “worked on the horrible process

whereby Jews were stripped of their rights,” Balkenende said before

he helped mark the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Westerbork transit

camp.

The Modern Period

In 1946, there were 30,000 Jews in the Netherlands,

just 20 percent of the pre-war population; of these, nearly a third were

partners in mixed marriages. The population had decreased by several

thousand by the mid-1950s, due to emigration and a low birthrate. In

fact, the emigration from the Netherlands to Palestine, and later to Israel, surpassed that of any other

Western European country. In many ways, the Jews of the Netherlands

were better-off after the Holocaust than they had ever been. Relations with non-Jews were friendly, and

reparation payments made the Jewish community very wealthy. Traditional

Jews, however, were few and far between, and organized community membership

dropped due to increased assimilation.

A WWII memorial stands in front

of the Amsterdam Ashkenazi Synagogue.

A WWII memorial stands in front

of the Amsterdam Ashkenazi Synagogue. |

To the present day, the

number of Jews in Amsterdam has held steady

at between 25,000 and 30,000. While the total

numbers have remained constant, however, levels

of observance have increased. Primarily due

to the presence of Chabad,

there are currently three Jewish schools in

Amsterdam, and the number of Jews affiliated

with communities has grown over the years. Kosher food is available in Amsterdam, the Hague,

and several other cities with Jewish populations.

Nonetheless, the majority of Jews are still

unaffiliated.

The relationship between the Netherlands and Israel

has been a mostly friendly one. The Netherlands voted in favor of partition in the U.N., and has frequently

defended Israel both in the U.N. and in the European Union. They have

provided sporadic military aid to Israel as well. However, the Netherlands

has at times refused to support Israel, and there is great deal of sympathy

for the Palestinian cause in the Dutch media. Nonetheless, the PLO,

and subsequently, the Palestinian

Authority, have been granted only limited recognition in the Hague,

the Netherlands' political capitol.

On November 25 2014, Holland's newly appointed Foreign Minister Bert Koenders expressed his support for negotiations towards a two state solution, and condemned the unilateral recognitions of Palestinian statehood that had recently been declared by Ireland, Britain, Spain, and Sweden. Koenders stated that this recognition of a Palestinian state by these countries "does not contribute to the priority issue of restarting negotiations" and that the Netherlands would recognize Palestine "at a strategic moment". Although he expressed support for the negotiations and disdain for the recognition of Palestine at this time, he also referred to the Israeli blockade of Gaza as collective punishment, and condemned the West Bank security barrier as a violation of international law. Groups involved in the BDS movement were hoping that Koenders would take a much harsher stance on Israel and were sorely dissapointed.

The Centre for Information and Documentation on Israel (CIDI), the main anti-Semitism watchdog organization of the Netherlands, reported in April 2015 that during 2014 the country experienced 171 anti-Semitic incidents, in contrast to 100 incidents during 2013. This reflects a worldwide trend, with anti-Semitic attacks globally increasing in frequency by 40% on average according to a report released by the Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry at Tel Aviv University. Rabbi Benjamin Jacobs, the leader of the Netherlands Jewish community, recommended solving the problem and combatting anti-Semitism through education.

The Dutch government issued a travel warning in June 2015 on it's website focusing on tourism in Israel, causing a stir with what was perceived as anti-Semitic rhetoric. The Dutch government posted travel warnings, urging Dutch citizens to avoid “Jewish colonists [who] live in illegal West Bank settlements and organize demonstrations,” when they travel to Israel. Dutch citizens were warned in this online posting that “the colonists are sometimes violent. At times, these colonists throw stones at Palestinians and international vehicles.” The warning advises Dutch citizens to stay away from Gaza as a general statement, stating that they may become a victim of an Israeli aerial attack, or may be caught in crossfire between radical Islamic groups.

During a visit to the Netherlands in September 2016 Israeli and Dutch officials committed to jointly improving water and energy supplies to Gaza, although no plans were specified.

Amsterdam

Today, the Jewish quarter, which was destroyed during

the Nazi occupation, has been largely abandoned; only the “Snoga,”

the Sephardi synagogue remains in use there. Nonetheless, the quarter is still full of monuments

and historical sights. The Rembrandthuis (Rembrandt House) is located

on Jodenbreestraat, and contains a collection of his works. Among the

pieces displayed there are numerous biblical scenes, and several portraits

of prominent seventeenth century Jews.

A painting of an Ashkenazi synagogue

in Amsterdam.

A painting of an Ashkenazi synagogue

in Amsterdam. |

Not far from the Rembrandthuis are several restored

synagogues. A large complex houses the Great Shul (built in 1670), the

Obbene Shul (1672), the Dritt Shul (1700) and the Neie Shul (1730);

all four were badly damaged during WWII and its aftermath, and have

recently been renovated. The shuls reflect the rapid growth of Dutch Ashkenazi Jewry in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – each synagogue was constructed

when the previous one proved too small for the expanding community.

The complex also contains a mikva and houses the Jewish Historical Museum, which has a large collection

of memorabilia and ritual objects.

Around the corner, on Plantage Middenlaan, is the Hollandsche Schouwberg.

The spot was once the site of Jewish dramatic performances; later, it

was the gathering spot for Jews who were rounded up and deported by

the Nazis. A Holocaust memorial stands there today.

The Beth Chayim Sephardi cemetery,

which dates back to 1614.

The Beth Chayim Sephardi cemetery,

which dates back to 1614. |

The “Snoga,” the Sephardi synagogue that has been in almost continual use since 1672, stands nearby.

It is famous for its magnificent interior, its sand covered floors,

and its library, which contains priceless copies of some of the scholarly

works that made Amsterdam famous during the Golden Age. Down the road,

on Waterlooplein, is the site where the previous Sephardi shul stood,

in which Baruch Spinoza was excommunicated. The house he grew up in is nearby as well, and today

houses a church.

The Anne Frank House, at Prinsengracht 263, is one of the most visited sites in all

of the Netherlands. The small house in which the Frank and Van Damm

families hid for two years today houses a museum. Much of the house,

however, has not been changed from its original state: posters of movie

stars still hang on the wall of what was Anne's bedroom, and the kitchen

walls are marked with pencil lines where the family marked their children's

growth spurts.

Ther government of Amsterdam announced on May 23, 2016, that they would be compensating the city's Jewish community to the tune of $11 million, to make up for taxes imposed on Holocaust survivors returning to the city following World War II. Survivors were forced to pay taxes as well as insurance fees when they returned, on homes left vacant after the owners were forcibly taken away by the Nazis. Amsterdam's government decided to give the money to the Jewish community because finding the individual people or relatives entitled to compensation would be too long and arduous a process.

The Hague

The seat of the Dutch government is less cosmopolitan

than Amsterdam, but it too contains important history. Many Jews lived,

and still live, in this city, most notably Baruch

Spinoza during the last years of his life. There are several museums

located in the houses he occupied, which are run by the Spinoza Society.

Additionally, his grave is located in the Churchyard of the Nieuwe Kirk

(New Church). While his excommunication prevented him from being buried

in a Jewish cemetery, a memorial adorned with the Hebrew word “amcha”

(“your people”) was placed on the site in 1956 by the Israel

Spinoza Society, on the 300th anniversary of his excommunication.

Also in the Hague is a Jewish Community center, and

several synagogues. The most popular attraction in the city is the Madurodam,

a miniature city on a 1:25 scale in which cars and busses move, windmills

turn, and music and lights go on and off. The model was built by the

Maduro family in memory of George Maduro, a Jewish military hero who

died in Dachau.

Middelburg

Middelburg was one of the first cities in the Netherlands where Jews could express their religion freely. The synagogue in Middelburg

was founded in 1705 and was the first synagogue to be built outside of Amsterdam. During the Holocaust, Middelburg's small Jewish community of 200 was first transported to Amsterdam in 1942 and from there was sent to concentration camps in Eastern Europe. The Germans used the synagogue as a storehouse during the war and the building was later severely damaged during the liberation of 1944.

Only six of Middelburg's Jews returned to the city after the war. Without a Jewish community, Middelburg's synagogue fell into decay and by 1980, only a few walls remained intact. In 1987, the Stichting Synagoge Middelburg, the Middelburg Synagogue Foundation, was formed to undertake the resoration of the synagogue. The restoration was completed in 1994 and it is now possible to go visit one of the oldest surviving synagogues in the Netherlands between March and November, every Thursday from 10:00 untill 4:00.

Middleburg is also home to two Jewish cemeteries, one Ashkenazi and the other Sephardic. The Ashkenazi cemetery dates back to 1705 and is still in use today. The Sephardic cemetery was in use between 1655 and 1721

and was recently restored. Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel's son Samuel is buried at this cemetery. Ben Israel petitioned Oliver Cromwell in 1655 to allow the re-entrance of Jews to England and is believed to be partially responsible for Cromwell's decision in favor of their re-admittance. Both of Middelburg's Jewish cemeteries have been recognized as national monuments.

Sources: Sterling, Toby/Deutsch, Anthony. “Netanyahu says Netherlands, Israel to improve water, gas supply to Gaza,” Reuters, September 6, 2016);

“Amsterdam to pay Jewish community $11M for Holocaust survivor taxes,” JTA, (May 23, 2016);

“Attacks against Jews in the Netherlands have risen 71% in the past year, says Rabbi Benjamin Jacobs,” IBTimes, (April 17, 2015);

"Holland's 'idealist' foreign minister gets real on Palestine", JTA, (November 25 2014);

Encyclopedia

Britannica, “The Netherlands.”

Encyclopedia

Judaica, “The Netherlands.”

Tigay, Alan. The

Jewish Traveler. Jason Aronson,

Inc. Northvale, NJ, 1994.

Wigoder, Geoffery. Jewish Art and Civilization.

Walker and Co. New York, 1972.

Stichting Synagoge Middelburg (Middelburg Synagogue Foundation)

Photo Credits: Center for

Research on Dutch Jewry, at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

Ellen

Land-Weber, from her book To

Save a Life: Stories of Holocaust Rescue.

|