Iran Virtual Jewish History Tour

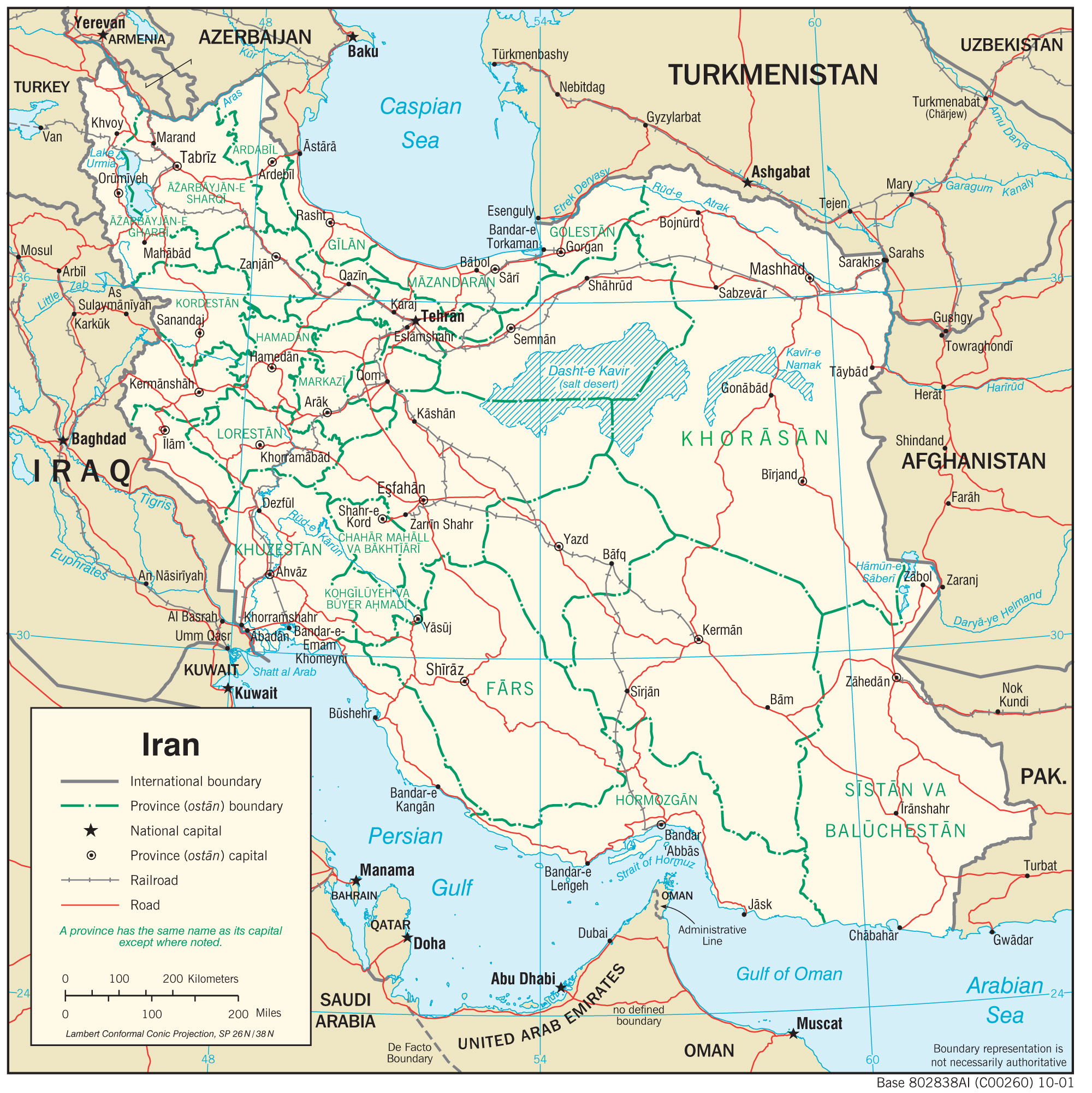

The Jewish community of Iran is one of the oldest in the Diaspora, with its roots reaching back to the 6th century B.C.E., the time of the First Temple. Jewish history in the pre-Islamic period of Iran is intertwined with that of neighboring Babylon. Jewish colonies were scattered from centers in Babylon to Persian provinces and cities such as Hamadan and Susa. The books of Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Daniel give a favorable description of the relationship of the Jews to the official government and court. The Iranian Jewish community is the largest Jewish community in the Middle East outside of Israel, and two-thirds of Iranian Jews live in the Iranian capital, Tehran. With the Islamization of the country, the overthrow of the Shah, and the declaration of an Islamic state in 1979, Iran severed relations with Israel and imposed strict control over Jewish institutions in the country. Today, Iran’s Jewish population – approximately 9,200 – is the second largest in the Middle East after Israel; however, reports vary as to the condition and treatment of this tight-knit community, and the population can only be estimated due to the community’s isolation from world Jewry. (See also Jews of Iran.) Population Population

The earliest report of a Jewish population in Iran goes back to the 12th century. It was Benjamin of Tudela who claimed that there was a population of about 600,000 Jews. This number was later reduced to 100,000 in the Safavid period (1501–1736), and it further diminished to 50,000 at the beginning of the 20th century, as reported by the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) emissaries in Iran. The drastic decrease in number was the result of persecution, forced conversions, Muslim laws of inheritance (which encouraged conversion and allowed the convert to inherit the properties of his Jewish family), and massacres. These problems continued at least up to the Constitutional Revolution in Iran (1905–09). According to unofficial statistics released by the Jewish Agency in Teheran, between 100,000 and 120,000 Jews were living in Iran in 1948. The following numbers, with some variation, were reported for the Jews of major cities: Teheran, about 50,000 Jews; all Iranian Kurdistan, between 15,000 to 20,000; Shiraz, 17,000; Isfahan, 10,000; Hamadan, 3,000; Kashan, 1,200; Meshed, 2,500; Kermanshah, 2,864; Yazd/Yezd, 2,000 (uncertain). There are no reliable statistics for other communities scattered in many small towns and villages, such as Borujerd, Dārāb, Fasā, Golpāygān, Gorgān, Kāzrun, Khunsār, Lahijān, Malāyer, Nowbandegān, Rasht, and many more. There were also censuses carried out once every ten years by the government, beginning in 1956. These censuses usually were not reliable as far as the Jewish communities were concerned since Jews were not enthusiastic about being identified as such. For example, the official census of 1966 cites 60,683 Jews in Iran, but the Jewish sources put the number much higher than 70,000. The data provided by different sources, especially by those involved or interested in Iran’s Jewish community affairs, differ greatly from one another. Today's Jewish community in Iran numbers approximately 8,300. OccupationWe do not possess a reliable source regarding the occupations of the Jews in different towns and settlements in Iran. The data varies in time and place, but one may nevertheless find similarities in the reports. We have more reliable statistics concerning the second largest community in Iran, the Jews of Shiraz which may, to some degree, represent the Jewish occupations in other major cities – with the exception of the goldsmiths and musicians who made Shirazi Jews famous. The following was reported by Dr. Laurence Loeb, who resided in Shiraz from August 1967 through December 1968, as investigated and reported on the distribution of occupations. In addition, Loeb found in Shiraz 41 persons who were dentists, cooks, carpenters, barbers, seed merchants, laborers, librarians, restaurant workers, bath attendants, leather tanners, photographers, beauty parlor attendants, appliance store clerks, lambswool merchants or dairy store attendants. They constituted 10.12 percent of the workforce of the community. There were also eight unemployed persons (1.98%). Most Jews living in Iran find it preferable to own their own business or work for themselves instead of working at a larger organization where they may face discrimination. EducationModern Jewish education in Iran has generally been in the hands of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) since 1898. The AIU was active only in major cities such as Teheran (from 1898), Hamadan (1900), Isfahan (1901), Shiraz (1903), Sanandaj (1903), and Kermanshah (1904). In the second decade of the 20th century, it opened schools in Kashan and Yazd and also in some small towns close to Hamadan, such as Tuyserkān, Borujerd, and Nehāvand. Parallel to the AIU schools, community schools were established in a few towns, such as Koresh in Teheran and Koresh in Rasht. During the Pahlavi regime, some Jews also studied in non-Jewish schools. In 1946/47, the Oẓar ha-Torah schools were opened in Teheran and other cities. Rabbi Isaac Meir Levi, a Polish Jew who had come to Iran in 1941 to organize the dispatch of parcels to rabbis and synagogues in Russia, was appointed by the Oẓar ha-Torah center in New York to establish a network of schools in Iran. Given the great wave of immigration to Israel which swept the Jews of Iran in the 1950s, most immigrants being poor and unskilled, the economic prosperity that Iran enjoyed in the 1960s and 1970s, and the rise to wealth of a large segment of the remaining Jewish community, more attention was devoted to education. In 1977/78, there were in Teheran 11 Oẓar ha-Torah schools, 7 AIU schools, and six community schools, including one ORT vocational school and the Ettefāq school belonging to Iraqi Jews resident in Teheran. This picture changed drastically with the mass exodus of Jews resulting from the Islamic revolution. Before the Islamic Republic of Iran (= IRI), there were three Jewish schools in Shiraz and one in each major city. By the end of the 20th century, there were generally three Jewish schools in Teheran, one in Shiraz and one in Isfahan. Most of these schools were funded and sponsored by Oẓar ha-Torah (Netzer, 1996). Aliyah to IsraelImmigration to Israel was facilitated and accelerated through the Zionist Association in Teheran (founded in 1918) and its branches in 18 major cities. The following official statistics published by the Government of Israel show the rate of Iranian Jewish immigration to Israel (the number 3,536 below for the years 1919–1948 does not accurately reflect reality since thousands of Iranian Jews immigrated to Israel illegally and were consequently not registered by the British Mandate or the Jewish Agency). It is believed that on the eve of independence, about 20,000 Iranian Jews were living in Israel. In the past, the majority of Iranian Jews lived in Jerusalem, while at the beginning of the 21st century, they were to be found primarily in Tel Aviv, Holon, Bat-Yam, Rishon le-Zion, Kefar Saba, Nes Ẓiyyonah, and Reḥovot. A smaller number chose to reside in Jerusalem, Netanya, Haifa, Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Beersheba. Since 1948, the Jews of Iran have founded several moshavim: Agur, Amishav (now a quarter in Petaḥ Tikvah), With the change of the regime and Khomeini’s rise to power, about three-quarters of Iran’s 80,000 Jews left. Many immigrated to Israel and the United States, but some preferred settling in European countries. The official statistics of Israel show that in 2001, there were 135,200 Jews who were considered Iranian either as olim or as individuals, one of whose parents was Iranian-Jewish. The above figure includes 51,300 who were born in Iran and 83,900 who were born in Israel. Iranian Jews in Israel became active and reached high ranks in academic life, in the socioeconomic realm, politics, and the military. Since 1955, they have had about a score of university teachers; Rabbi Ezra Zion Melamed, professor of Talmud at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was granted the Israel Prize. There have been several Knesset members, two chief commanders of the Air Force (General Eitan Ben-Eliyahu and General Dan Halutz), two army chiefs of staff (Major-General Shaul Mofaz and Major-General Dan ?alu?); one defense minister, Shaul Mofaz; one Sephardi chief rabbi (Rabbi Bakshi Doron); and one president of the State of Israel, Moshe Katzav. Representation in the MajlesThe Jewish representatives in the Iranian Parliament (Majles) since its inception (1907) were the following: Azizollah Simāni, a merchant (replaced by Ayatollah Behbāhni after only a few months); Dr. Loqmān Nehoray, a physician (1909–23); Shemuel Haim, a journalist (1923–26); Dr. Loqmān Nehoray (1926–43), Morād Ariyeh, a merchant (1945–56); Dr. Mussa Berāl, a pharmacologist (1956–1960), Morād Ariyeh, (1960–64), Jamshid Kashfi, a merchant (1964–68), Lotfollah Hay, a merchant (1968–75), and Yosef Cohen, a lawyer (1975–79), Aziz Daneshrad (1980), Manuchehr Eliasi (1996-2000), Maurice Motamed (2000-2008), and Siamak Moreh Sedgh (2008-2020). Iran-Israel RelationsRelations between the Yishuv and Iran began in 1942 when the Jewish Agency opened a Palestine Office in Teheran to assist the Jewish-Polish refugees from Russia and arrange for their immigration to the Land of Israel. This office continued to function until 1979. Iran voted, together with the Muslim and Arab states in the UN, against the partition of Palestine (November 29, 1947). In the Israel-Arab conflict, Iran sided with the Arabs. However, Iran’s need for socioeconomic reforms drove it to establish closer relations with the West, especially with the U.S. Consequently, after the Shah’s trip to the U.S. in 1949, Iran gave Israel de-facto recognition in March 1950. The relations between the two countries remained “discreetly unofficial,” even though diplomatic missions were operating in Teheran and Tel Aviv. These continued to function until early 1979. Practical relations between the two states existed in a variety of fields such as trade, export-import, regular El Al flights to Teheran, supply of Iranian oil to Israel, and student exchanges. They developed especially strong relations in three major fields: agriculture, medicine, and the military. Israeli experts assisted Iran in various development projects such as the Qazvin project in the 1960s. The Six-Day War is regarded as the high point of friendly Israel-Iran relations, particularly in the Intelligence Service. The Shah and his military were surprised by the swift Israeli victory over Syria, Jordan, and Egypt. Likewise, the Israeli setback in the Yom Kippur War (1973) induced the Shah’s pragmatic diplomacy to develop amicable relations with Anwar Sadat of Egypt. It has been said that it was this policy of the Shah that encouraged Sadat to make peace with Israel. With Khomeini coming to power in February 1979, the friendly relations between the two states changed into enmity. In 2006, the growing Iranian nuclear threat and President Ahmadinejad’s declaration that Israel should be wiped off the face of the earth led to increasing talk of a preemptive military strike against Iran. In August 2017, the Iranian government banned two soccer players on Iran’s national team for life after they competed against a team of Israelis while playing for Greece during a club team match. The two players, Masoud Shojaei, 33, the captain of the Iranian national team, and Ehsan Haji Safi, 27, had during the previous week played a game for their Greek club team Panionios against the Maccabi Tel Aviv team from Israel. Iran adopted a law in June 2020 entitled “Countering Israel’s Actions,” which describes Israel as a virulent and malign state and bans commercial, academic, and cultural activities, political agreements, negotiations, and exchanges of information “with official and unofficial Israeli entities.” Entities that “work for the goals of the Zionist regime and international Zionism all over the world” and companies in which “over half of the shares belong to Israeli citizens” are included in the ban. The law also forbids the use of hardware and software developed in Israel or by companies with production branches in Israel. Enforcement of some provisions will be impossible to enforce and would compel Iranians to abandon modern technology. In April 2021, Iran was suspended by judo’s world governing body as punishment for refusing to let its athletes face opponents from Israel. The International Judo Federation began considering the ban when former world champion Saeid Mollaei left the Iranian team in 2019, claiming he was ordered to lose world championship matches to avoid facing Israelis. In December 2023, Iran carried out a series of executions of suspected spies for the Mossad. One man was killed in the middle of the month, and four other “saboteurs,” three men and a woman, were put to death at the end of the year. In May 2025, Iran executed Pedram Madani, who was accused of spying for Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency. According to the Iranian judiciary’s Mizan news agency, Madani had been arrested in 2020 for allegedly attempting to pass classified information about sensitive Iranian sites to Israel and for illegally amassing wealth. Just a month earlier, another Iranian, Mohsen Langarneshin, was also executed on similar charges. See also: Iran Nuclear History Jews in the Pahlavi RegimeThe economic boom of the 1960’s and the 1970’s in Iran benefited the Jews too. Many Jews became rich, enabling them to provide their children with higher education. In 1978, there were about 80,000 Jews in the country, constituting one-quarter of one percent of the general population. Of these Jews, 10 percent were very rich, the same percentage were poor (aided by the Joint Distribution Committee), and the rest were classified as from middle class to rich. Approximately 70 out of 4,000 academicians teaching at Iran’s universities were Jews; 600 Jewish physicians constituted six percent of the country’s medical doctors. Some 4,000 Jewish students studied in universities, representing four percent of the total students. Never in their history were the Jews of Iran elevated to such a degree of affluence, education, and professionalism as they were in the last decade of the Shah’s regime. All this changed with the emergence of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Jews in the RevolutionOn September 1, 1978, the Jewish representative in the Majlis, Yosef Kohan, went with another member of parliament, Ahmad Bani-Ahmad, to see Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Kazim Shari‘atmadari to ask him to stop the growing incitement against Jews. The Ayatollah was willing to defend Jews if they were not agents of Israel. Fearing that Jews would be assumed to be working for Israel and targeted, Bani-Ahmad suggested that Shari‘atmadari issue a more general statement, which he made that evening: Reports are reaching us that a series of written threats against religious minorities who are recognized by the Constitution and respected by the Iranian Nation have begun under the name of the Clergy and the banner of Islam….I shall never accept the smallest threat or intimidation against them under the name of Islam. In fact, I consider such actions as an anti-Iranian and anti-Islamic conspiracy. We must know that irresponsible people with missions of sabotage are on the prowl and are hoping to spread the seeds of hate and disunity. A week later, mass demonstrations, which included many Jewish participants, erupted in Tehran. The Shah sent the army to quell the unrest and shot many of the protesters in what became known as Black Friday. Many of the casualties were taken to the Jewish hospital – Sapir Hospital. Rumors spread that the Shah had Israeli soldiers to confront the protesters. Nissim Levy, one of the Israeli embassy’s security officers, said he later saw graffiti around Tehran that said, “Kill Every Israeli—But Do Not Harm the Jews.” Larger demonstrations occurred in December, with as many as 5,000 Jews involved. A few weeks later, on January 15, 1979, the Shah left Iran. Shortly after that, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran with a delegation of Jews among those who greeted him at the airport. Lior Sternfeld said many Jews undoubtedly recognized the Shah’s days were numbered. Jews who participated in and welcomed the revolution were mainly from the younger generation. She explained: Whereas members of their parents’ generation in the late 1960s and early 1970s spent their own youths paving the way to leave the ghettos and the Jewish traditional life in order to pursue education and careers in the private and public sectors, their children felt they had to fight not for their status as a marginal minority but rather for a better society for Iran. Iranian Jews AbroadIt is estimated that during the first 10 years of the Islamic regime, about 60,000 Jews left Iran; the rest, some 20,000, remained in Teheran, Shiraz, Isfahan, and other provincial cities. Of the 60,000 Jews who emigrated, about 35,000 preferred to immigrate to the U.S.; some 20,000 left for Israel, and the remaining 5,000 chose to live in Europe, mainly in England, France, Germany, Italy, or Switzerland. The spread of Iranian Jews in the U.S. provides us with the following demographic map: of the total 35,000; some 25,000 live in California, of whom about 20,000 prefer to dwell in Los Angeles; 8,000 Iranian Jews live in the city of New York and on Long Island; the remaining 2,000 live in other cities, mainly in Boston, Baltimore, Washington D.C., Detroit, or Chicago. In every city abroad, the Jews of Iran tried to establish themselves in their own newly founded organizations and synagogues. In Los Angeles alone, they set up more than 40 organizations, 10 synagogues, about 6 magazines, and one television station. The Iranian Jewish community in the U.S. is, for the most part, well-educated and financially stable. Education is one of the strongest values stressed by the Iranian Jewish community, which considers itself the cream of all immigrant groups in the U.S. The Iranian Jews brought money, doctors, engineers, upper-class, educated businessmen, and professionals in almost all fields. Many became wealthy in their new homes in the U.S., Europe, and Israel. Jewish Musical TraditionThe musical patrimony of the Iranian Jews contains several different styles. The nature of their non-synagogal music, the general approach to music, and how it is performed are identical to those of their non-Jewish neighbors. The attachment to poetry and music, which has been characteristic of Iranian culture from its earliest days, is also found among the Jews, with similar attention devoted to the cultivation of these arts, the special connection of music with the expressions of sorrow, meditation, and mystical exaltation, and the same ideal of voice color and voice production. Some of these characteristics have been transposed to suit the specific conditions of a Jewish culture. The tendency toward mysticism finds its fullest expression in a predilection for the Zohar, which is recited with a special musical intonation. The great importance attached to lamentations for the dead, which constitute a rich and interesting repertoire, may be analogous with the ta’ziya-t of the Persian Shi’ites, which are a kind of vernacular religious drama commemorating the tragedies that marked the birth of the Shi’a sect. Notwithstanding some analogies in style and form, the Iranian influence is hardly traceable in the Iranian synagogal tradition. In the structure of the free rhythmical or recitative character melodies, A.Z. Idelsohn found a strong resemblance to the synagogal tradition of the Yemenite Jews. Their tradition of Pentateuch cantillation is among the more archaic ones, centered almost exclusively on the major divisive accents (see Masoretic Accents, Musical Rendition). On the other hand, most of the metrical piyyutim, mainly those of the High Holidays, are sung to melodies common to all Near Eastern, i.e., “Eastern Sephardi,” communities. In the paraliturgical and secular domain, the poetry and music of the Iranian Jews are simply a part of the general culture, with a few exceptions. Among these are the works of non-Persian Jewish poets, such as Israel Najara, of which a Judeo-Persian translation is in wide use, and which are sung on such occasions as se’udah shlishit and bakkashot (among Persians Jews, contrary to other communities, these are performed at home and not in the synagogue). The most impressive production was in the domain of epic songs. Here, the Persian Jews closely followed the Persian model in language, meter, and musical rendition. However, the Jewish poets and musicians naturally sang of the achievements and history of their own people. The chief representative of epic poetry is Shahin, a Persian-Jewish poet of the 14th century. His poetic paraphrase of the narrative parts of the Pentateuch, called in brief Sh?h?n, is sung in public on Sabbath afternoons and at festive gatherings by specialized “epic singers.” Although they know every word by memory, the public expresses its enthusiasm anew each time. The Shah?n also became a favorite in Bukhara, which was considered a cultural province of Persian Jewry. Shahin himself and, after him, other poets, especially ‘Amrani, wrote other epic songs on Jewish topics which also attained great popularity. Another branch of poetry, but one of a more folkloristic nature, consists of songs that are improvised in an impromptu competition of poets. These are performed at family celebrations, after wine-drinking bouts, and the competition between the two singer-poets adds to the atmosphere of good cheer. The Iran-Iraq WarAs with all Iranian citizens, Jewish Iranian citizens are drafted into the army, and during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) many Jewish citizens fought in the Iranian military. Over one million lives were lost in total, and about 150 Iranian Jewish soldiers were killed in combat. In early December 2014, Iran unveiled a “Monument to the Jewish Martyrs” in Tehran, consisting of a beautiful cemetery and memorial commemorating the Jewish individuals who died fighting in the Iran-Iraq war. The dedication ceremony for the monument was attended by high-ranking Iranian officials, including members of the Iranian Parliament, who praised the Jewish community in Iran for supporting the government and being obedient to Supreme Leader Khamenei. Anti-SemitismSince the revolution, the Iranian government has been rabidly anti-Semitic. In 2016, a Jewish Studies Center was established, which has published more than 1,000 anti-Semitic articles, reports, comment pieces, books, and videos. Ismail Haniyeh's AssasinationOn July 31, 2024, it was reported that Iranian Jews are living in fear of retaliation from the regime after the alleged assassination of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh by Israel in Tehran. A letter from the Tehran Jewish community condemned the killing and expressed solidarity with Haniyeh, labeling him a martyr. This forced show of loyalty is seen as a humiliating submission to the Iranian regime, which exerts severe pressure on religious minorities. The Jewish community, alongside Christians and Zoroastrians, publicly denounced the assassination in a parliamentary letter, reflecting their precarious status as second-class citizens under a totalitarian regime. Despite being coerced into these actions, Iran's Jews, now numbering around 9,000, continue to face systemic discrimination and are subjected to coercive measures, such as being forced to vote in elections, highlighting their vulnerability and marginalization in Iranian society. BIBLIOGRAPHYE. Abrahamian, Iran Between the Two Revolutions (1982); P. Avery, Modern Iran (1965); Bulletin de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle, Paris; I. Ben-Zvi (1935), Nidhei Yisrael (1935, 1965); Sh. Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollas: Iran and the Islamic Revolution (1984); A. Banani, The Modernization of Iran: 1921–1941 (1961); U. Bialer, “The Iranian Connection in Israel’s Foreign Policy,” in: The Middle East Journal, 39 (Spring 1985), 292–315; G.N. Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question, 1–2 (1892), index; R. Graham, Iran: The Illusion of Power (1979); F. Halliday, Iran: Dictatorship and Development (1979); Sh. Hillel, Ruah Qadim (1985); S. Landshut, Jewish Communities in the Muslim Countries of the Middle East (1950), 61–6; G. Lenczowski, Russia and the West in Iran, 1918–1948 (1949); idem, Iran under the Pahlavis (1978); H. Levy, History of the Jews of Iran, vol.3, (1960); A. Netzer, “Be’ayot ha-Integra?ya ha-Tarbutit, ha-?evratit ve-ha-Politit shel Yehudei Iran,” in: Gesher, 25:1–2 (1979), 69–83; idem, “Yehudei Iran, Israel, ve-ha-Republikah ha-Islamit shel Iran; in: ibid., 26:1–2 (1980), 45–57; idem, “Iran ve-Yehudeha be-Parashat Derakhim Historit,” in: ibid., 1/106 (1982), 96–111; idem, “Tekufot u-Shelavim be-Ma?av ha-Yehudim ve-ha-Pe’ilut ha-?iyyonit be-Iran,” in: Yahdut Zemanenu, I (1983), 139–62; idem, “Yehudei Iran be-Ar?ot ha-Berit,” in: Gesher, 1/110 (1984), 79–90; idem, “Anti-Semitism be-Iran, 1925–1950,” in: Pe’amim, 29 (1986), 5–31; idem, “Jewish Education in Iran,” in: H.S. Himmelfarb and S. DellaPergola (eds.), Jewish Education Worldwide, (1989), 447–61; idem, “Immigration, Iranian,” in: J. Fischel and S. Pinsker (eds.), Jewish-American History and Culture (1992), 265–67; idem, “Persian Jewry and Literature: A Socio-cultural View,” in: H.E. Goldberg (ed.), Sephardi and Middle Eastern Jewries (1996), 240–55; J. Nimrodi, Massa’ Hayyay, 1–2 (2003); The Palestine Year Book, 3 (1947–1948), 77; R.K. Ramazani, Revolutionary Iran (1986), 282–5; idem, The Foreign Policy of Iran: 1500–1941 (1966); Sh. Segev, Ha-Meshullash ha-Irani (1981); Ha-Shenaton ha-Statisti le-Israel (2002); Shofar (Jewish monthly in Persian published on Long Island), 243 (May 2001), 22ff.; B. Souresrafil, Khomeini and Israel (1988); J. Upton, The History of Modern Iran: An Interpretation (1968); D.N. Wilbur, Iran, Past and Present (1948); M. Yazdani, Records on Iranian Jews Immigration to Palestine (1921–1951) (1996), 61, 67, 110; Idelson, Melodien, 3 (1922). Sources: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved. |