Alexandria, Egypt

ALEXANDRIA, city in northern *Egypt.

Ancient Period

Jews settled in Alexandria at the beginning of the third century B.C.E. (according to Josephus, already in the time of Alexander the Great). At first they dwelt in the eastern sector of the city, near the sea; but during the Roman era, two of its five quarters (particularly the fourth (= "Delta") quarter) were inhabited by Jews, and synagogues existed in every part of the city. The Jews of Alexandria engaged in various crafts and in commerce. They included some who were extremely wealthy (moneylenders, merchants,

*alabarchs

), but the majority were artisans. From the legal aspect, the Jews formed an autonomous community at whose head stood at first its respected leaders, afterward – the ethnarchs, and from the days of Augustus, a council of 71 elders. According to Strabo, the ethnarch was responsible for the general conduct of Jewish affairs in the city, particularly in legal matters and the drawing up of documents. Among the communal institutions worthy of mention were the bet din and the "archion" (i.e., the office for drawing up documents). The central synagogue, famous for its size and splendor, may have been the "double colonnade" (diopelostion) of Alexandria mentioned in the Talmud (Suk. 51b; Tosef. 4:6), though some think it was merely a large meeting place for artisans. During the Ptolemaic period relations between the Jews and the government were, in general, good. Only twice, in 145 and in 88 B.C.E., did insignificant clashes occur, seemingly with a political background. Many of the Jews even acquired citizenship in the city. The position of the Jews deteriorated at the beginning of the Roman era. Rome sought to distinguish between the Greeks, the citizens of the city to whom all rights were granted, and the Egyptians, upon whom a poll tax was imposed and who were considered a subject people. The Jews energetically began to seek citizenship rights, for only thus could they attain the status of the privileged Greeks. Meanwhile, however,

*antisemitism

had taken deep root. The Alexandrians vehemently opposed the entry of Jews into the ranks of the citizens. In 38 C.E., during the reign of *Caligula, serious riots broke out against the Jews. Although antisemitic propaganda had paved the way for them, the riots themselves became possible as a result of the attitude of the Roman governor, Flaccus. Many Jews were murdered, their notables were publicly scourged, synagogues were defiled and closed, and all the Jews were confined to one quarter of the city. On Caligula's death, the Jews armed themselves and after receiving support from their fellow Jews in Egypt and Ereẓ Israel fell upon the Greeks. The revolt was suppressed by the Romans. The emperor Claudius restored to the Jews of Alexandria the religious and national rights of which they had been deprived at the time of the riots, but forbade them to claim any extension of their citizenship rights. In 66 C.E., influenced by the outbreak of the war in Ereẓ Israel, the Jews of Alexandria rebelled against Rome. The revolt was crushed by

*Tiberius Julius Alexander

and 50,000 Jews were killed (Jos., Wars, 2:497). During the widespread rebellion of Jews in the Roman Empire in 115–117 C.E. the Jews of Alexandria again suffered, the great synagogue going up in flames. As a consequence of these revolts, the economic situation of the community was undermined and its population diminished. See also

*Diaspora

.

[Avigdor (Victor) Tcherikover]

Alexandrians in Jerusalem

During the period of the Second Temple the Jews of Alexandria were represented in Jerusalem by a sizable community. References to this community, while not numerous, can be divided into two distinct categories: (1) The Alexandrian community as a separate congregation. According to Acts 6:9, the apostles in Jerusalem were opposed by "certain of the synagogue, which is called the synagogue of the Libertines and Cyrenians and Alexandrians, and of them of Cilicia and of Asia." The Alexandrian synagogue and congregation are mentioned in talmudic sources as well: "Eleazar b. Zadok bought a synagogue of the Alexandrians in Jerusalem" (Tosef. Meg. 3:6;

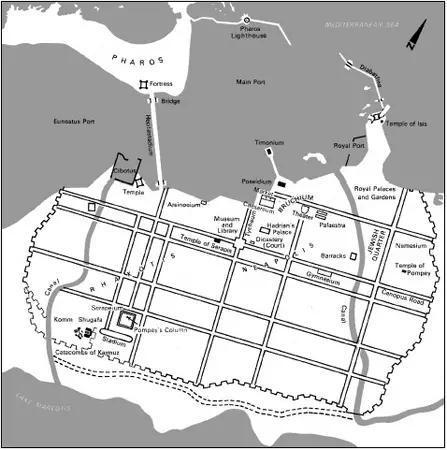

Alexandria in early Christian times. Alexandria in early Christian times.

cf. TJ Meg. 3:1, 73d). (2) References to particular Alexandrians. During Herod's reign several prominent Alexandrian Jewish families lived in Jerusalem. One was that of the priest Boethus whose son Simeon was appointed high priest by Herod. Another family of high priests, the "House of Phabi," was likewise of Jewish-Egyptian origin, although it is not certain whether they came from Alexandria. According to Parah 3:5, Ḥanamel the high priest, who had been appointed by Herod in place of Aristobulus the Hasmonean, was an Egyptian, also probably from Alexandria. "

*Nicanor

's Gate" in the Temple was named after another famous Alexandrian Jew. Rabbinic sources describe at length the miracles surrounding him and the gates he brought from Alexandria (Mid. 1:4; 2:3; Yoma 3:10; Yoma 38a). In 1902 the family tomb of Nicanor was discovered in a cave just north of Jerusalem. The inscription found there reads: "The bones of the sons of Nicanor the Alexandrian who built the gates. Nicanor Alexa."

Jewish Culture

The Greek-speaking Jews of Alexandria were familiar with the works of the ancient Greek poets and philosophers and acknowledged their universal appeal. They would not, however,

give up their own religion, nor could they accept the prevailing Hellenistic culture with its polytheistic foundations and pagan practice. Thus they came to create their own version of Hellenistic culture. They contended that Greek philosophy had derived its concepts from Jewish sources and that there was no contradiction between the two systems of thought. On the other hand, they also gave Judaism an interpretation of their own, turning the Jewish concept of God into an abstraction and His relationship to the world into a subject of metaphysical speculation. Alexandrine Jewish philosophers stressed the universal aspects of Jewish law and the prophets, de-emphasized the national Jewish aspects of Jewish religion, and sought to provide rational motives for Jewish religious practice. In this manner they sought not only to defend themselves against the onslaught of the prevailing pagan culture, but also to spread monotheism and respect for the high moral and ethical values of Judaism. The basis of Jewish-Hellenistic literature was the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Bible, which was to become the cornerstone of a new world culture (see *Bible: Greek translations). The apologetic tendency of Jewish-Hellenistic culture is clearly discernible in the Septuagint. Alexandrine Jewish literature sought to express the concepts of the Jewish-Hellenistic culture and to propagate these concepts among Jews and Gentiles. Among these Jewish writers there were poets, playwrights, and historians; but it was the philosophers who made a lasting contribution. *Philo of Alexandria was the greatest among them, but also the last of any significance. After him, Alexandrine Jewish culture declined. See also *Hellenism.

Byzantine Period

By the beginning of the Byzantine era, the Jewish population had again increased, but suffered from the persecutions of the Christian Church. In 414, in the days of the patriarch Cyril, the Jews were expelled from the city but appear to have returned after some time since it contained an appreciable Jewish population when it was conquered by the Muslims.

Arab Period

According to Arabic sources, there were about 400,000 Jews in Alexandria at the time of its conquest by the Arabs (642), but 70,000 had left during the siege. These figures are greatly exaggerated, but they indicate that in the seventh century there was still a large Jewish community. Under the rule of the caliphs the community declined, both demographically and culturally.

J. *Mann

concluded from a genizah document of the 11th century that there were 300 Jewish families in Alexandria, but this seems improbable. The same is true for the statement of

*Benjamin

of Tudela, who visited the town in about 1170 and speaks of 3,000 Jews living there. In any case, throughout the Middle Ages there was a well-organized Jewish community there with rabbis and scholars. Various documents of the Cairo Genizah mention the name of Mauhub ha-Ḥazzan b. Aaron ha-Ḥazzan, a dayyan of the community in about 1070–80. In the middle of the 12th century Aaron He-Ḥaver Ben Yeshuʿah

*Alamani

, physician and composer of piyyutim, was the spiritual head of the Alexandrian Jews. Contemporary with

*Maimonides

(late 12th century) were the dayyanim Phinehas b. Meshullam, originally from Byzantium, and

*Anatoli b. Joseph

from southern France, and contemporary with Abraham the son of

*Maimonides

was the dayyan Joseph b. Gershom, also a French Jew. In this period the community of Alexandria maintained close relations with the Jews of Cairo and other cities of Egypt, to whom they applied frequently for help in ransoming Jews captured by pirates. A letter of 1028 mentions this situation; it also praises Nethanel b. Eleazar ha-Kohen, who had been helpful in the building of a synagogue, apparently the synagogue of the congregation of Palestinians that may have been destroyed during the persecution of the non-Muslims by the Fatimid caliph al-Ḥākim (c. 996–1021). In addition to this synagogue there was a smaller one, attested to in various medieval sources that mention two synagogues of Alexandria, one of them called "small." The Jews of Alexandria were engaged in the international trade centered in their city, and some of them held government posts.

Mamluk and Ottoman Periods

Under the rule of the Mamluk sultans (1250–1517), the Jewish population of Alexandria declined further, as did the general population.

*Meshullam

of Volterra, who visited it in 1481, found 60 Jewish families, but reported that the old men remembered the time when the community numbered 4,000. Although this figure is doubtless an exaggeration, it nevertheless testifies to the numerical decrease of the community in the later Middle Ages. In 1488 Obadiah of Bertinoro found 25 Jewish families in Alexandria. Many Spanish exiles, including merchants, scholars, and rabbis settled there in the 14th–15th centuries. The historian

*Sambari

(17th century) mentions among the rabbis of Alexandria at the end of the 16th century Moses b. Sason, Joseph Sagish, and Baruch b. Ḥabib. With the spread of the plague in 1602 most of the Jews left and did not return. After the Cossack persecutions of 1648–49 (see *Chmielnicki) some refugees from the Ukraine settled in Alexandria. During the 1660s the rabbi of the city was Joshua of Mantua, who became an ardent follower of

*Shabbetai Ẓevi

. In 1700 Jewish fishermen from *Rosetta (Rashīd) moved to Alexandria and formed a Jewish quarter near the seashore, and in the second half of the 18th century more groups of fishermen from Rosetta, *Damietta, and Cairo joined them; this Jewish quarter was destroyed by an earthquake. At the end of the 18th century the community was very small and it suffered greatly during the French conquest. Napoleon imposed heavy fines on the Jews and ordered the ancient synagogue, associated with the prophet Elijah, to be destroyed. In the first half of the 19th century under the rule of Muhammad ʿAli there was a new period of prosperity. The development of commerce brought great wealth to the Jews, as to the other merchants in the town; the community was reorganized and established schools, hospitals, and various associations. From 1871 to 1878

the Jewry of Alexandria was divided and existed as two separate communities. Among the rabbis of Alexandria in modern times were the descendants of the Israel family from Rhodes: Elijah, Moses, and Jedidiah Israel (served 1802–30), and Solomon Ḥazzan (1830–56), Moses Israel Ḥazzan (1856–63), and Bekhor Elijah Ḥazzan (1888–1908). As a result of immigration from Italy, particularly from Leghorn, the upper class of the community became to some extent Italianized. Rabbis from Italy included Raphael della Pergola (1910–23), formerly of Gorizia, and

David *Prato

(1926–37). Later rabbis were

M. *Ventura

and Aharon Angel. During World War I many Jews from Palestine who were not Ottoman citizens were exiled to Alexandria. In 1915 their leaders decided, under the influence of

*Jabotinsky

and

*Trumpeldor

, to form Jewish battalions to fight on the side of the Allies; the Zion Mule Corps was also organized in Alexandria.

Modern Times

In 1937, 24,690 Jews were living in Alexandria and in 1947, 21,128. The latter figure included 243 Karaites, who, unlike those of Cairo, were members of the Jewish community council. Ashkenazi Jews were also members of the council. According to the 1947 census, 59.1% of Alexandrian Jews were merchants, and 18.5% were artisans. Upon the outbreak of the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, several Jews were placed in detention camps, such as that at Abukir. Most of the detainees were released before 1950. There were several assaults on the Jewish community by the local population, including the throwing of a bomb into a synagogue in July 1951. With

*Nasser

's accession to power in February 1954, many Jews were arrested on charges of

*Zionism

, communism, and currency smuggling. After the

*Sinai Campaign

(1956), thousands of Jews were banished from the city, while others left voluntarily when the Alexandrian stock exchange ceased to function. The 1960 census showed that only 2,760 Jews remained. After the

*Six-Day War

of June 1967, about 350 Jews, including Chief Rabbi Nafusi, were interned in the Abu Za'bal detention camp, known for its severe conditions. Some of them were released before the end of 1967. The numbers dwindled rapidly; by 1970 very few remained and in 2005 just a few dozen, mostly elderly people.

Hebrew Press

The first Hebrew press of Alexandria was founded in 1862 by Solomon Ottolenghi from Leghorn. In its first year, it printed three books. A second attempt to found a Hebrew press in Alexandria was made in 1865.

Nathan *Amram

, chief rabbi of Alexandria, brought two printers from Jerusalem, Michael Cohen and Joel Moses Salomon, to print his own works. However, these printers only produced two books, returning to Jerusalem when the second was only half finished. A more successful Hebrew press was established in 1873 by Faraj Ḥayyim Mizraḥi, who came from Persia; his press continued to operate until his death in 1913, and his sons maintained it until 1916. Altogether, over 40 books were printed. In 1907 Jacob b. Attar from Meknés, Morocco, founded another press, which produced several dozen books. Apart from these main printing houses, from 1920 on the city had several small presses, each producing one or two books. A total of over 100 books for Jews were printed in Alexandria, most of them in Hebrew, the others in Judeo-Arabic and Ladino. Most of them were works by eminent Egyptian rabbis, prayer books, and textbooks.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

ANCIENT TIMES: V.A. Tcherikover, Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews (1959), index; idem, Corpus papyrorum… judaicarum, 1 (1957), index; Klausner, Bayit Sheni, 4 (19502), 267–86; A. Bludau, Juden und Judenverfolgungen im alten Alexandrien (1906); H.I. Bell, Jews and Christians in Egypt (1924); idem, Juden und Griechen im roemischen Alexandreia (1926). ALEXANDRIANS IN JERUSALEM: PEFQS (1903), 125–31, 326–32; E.L. Sukenik, in: Sefer Zikkaron… Gulak ve-Klein (1942), 134–7; Schuerer, Gesch, 2 (19074), 87 n. 247, 502, 524 n. 77; S. Lieberman, Tosefta ki-Feshutah, 5 (1962), 1162; Stern, in: Tarbiz, 25 (1965/66), 246. ARAB PERIOD: Mann, Egypt, 1 (1920), 88; Ashtor, Toledot, 1 (1944), 247–8; 2 (1950), 111–2; 3 (1970); idem, in: JJS, 19 (1968), 8 ff.; B. Taragan, Les communautés israélites d'Alexandrie (1932). OTTOMAN PERIOD: J.M. Landau (ed.), Toledot ha-Yedudim be Miẓrayim ha-Otmanit (1988), index; idem, Jews in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (1969), index; Tcherikover, Corpus, index; idem, Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews (1959), 541–9 (bibliography), and index; Toledano, in: HUCA, 12–13 (1937–38), 701–14. HEBREW PRINTING: A. Yaari, Ha-Defus ha-Ivri be-Arẓot ha-Mizraḥ, 1 (1937), 53–56, 67–85; idem, in: KS, 24 (1947/48), 69–70.

Source: Encyclopaedia

Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group.

All Rights Reserved.

|