The Expiration of the UN Ban on Iran Arms Transfers

(August 2020)

On August 14, 2020, the United States suffered an embarrassing diplomatic defeat when the UN Security Council rejected an American proposal to indefinitely extend an arms embargo on Iran. Russia and China voted against it and European nations abstained. Only the Dominican Republic voted with the U.S. Even if the U.S. could have convinced a majority to support the extension, China and/or Russia would have vetoed it.

The embargo was agreed to with the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2231, which is due to expire in October 18, 2020. It was imposed to prevent Iran from buying and selling weapons, including aircraft and tanks. The good news for Israel is that the expiration of the ban does not allow the sale of missile components to Iran.

After failing to convince the Security Council to renew the embargo, the Trump administration hopes to force the Council to adopt snapback sanctions even though the Europeans, who oppose them (and abstained on the U.S. resolution), are unlikely to cooperate and the Chinese and Russians have said they plan to ignore them.

“These will be fully a valid, enforceable UN Security Council resolution,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said. “We have every expectation that they’ll be enforced just like every other UN Security Council resolution that is in place.”

“We can’t allow the world’s biggest state sponsor of terrorism to buy and sell weapons,” Pompeo also said.

The other signatories to the agreement, however, do not believe the United States has the authority to ask for the snapback since Trump withdrew from the JCPOA. The U.S. disagrees and insists it has the legal standing to unilaterally trigger a sanctions snapback.

“Following the U.S. notification of snapback plans, the other members of the Security Council have 10 days to offer a measure opposing the sanctions, which the U.S. could then veto,” according to the Wall Street Journal. “The sanctions would come back into effect 30 days after the U.S. notification.”

The sanctions lifted after the JCPOA was signed include the prohibition of not just arms deals, but also oil sales and banking agreements.

It is possible Iran could withdraw from the JCPOA if the sanctions are imposed, but the other remaining signatories remain determined to keep the agreement in force. They are hopeful they can wait out Trump and that Joe Biden, who has said he wants to return to the deal, will be elected in November.

The following is an analysis of the issue by the Congressional Research Service.

Overview

A 2015 multilateral Iran nuclear agreement (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA), provides for limits on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. The accord, endorsed by UN Security Council Resolution 2231 (July 17, 2015), contains Annex B that provides for a ban on the transfer of arms to or from Iran until October 18, 2020. The Trump Administration, with the support of many in Congress, seeks to extend the ban to prevent Iran from acquiring new conventional weaponry, particularly advanced combat aircraft. However, on August 14, the UN Security Council, including two key potential arms suppliers of Iran—Russia and China—voted down a U.S. draft to extend the arms transfer ban. Members of the Council, including the European parties to the JCPOA, also oppose a U.S. plan to implement its longstanding threat to invoke the provision of Resolution 2231 that would snap back all UN sanctions on Iran—if the Council does not extend the arms transfer ban.

Annex B contains a ban until October 18, 2023, on supplying equipment with which Iran could develop nuclear-capable ballistic missiles and calls on Iran not to develop ballistic missiles designed to carry nuclear weapons.

Provisions of the Arms Transfer Ban

Annex B of Resolution 2231 restated and superseded the Iran arms transfer restrictions of previous UN Security Council resolutions. Resolution 1747 (March 24, 2007) banned Iran’s transfer of arms from its territory and required all UN member states to prohibit the transfer of Iranian arms. Resolution 1929 (June 9, 2010) banned the supply to Iran of “any battle tanks, armored combat vehicles, large caliber artillery systems, combat aircraft, attack helicopters, warships, missiles or missile systems as defined for the purpose of the United Nations Register of Arms [ballistic or cruise missiles capable of delivering a warhead or weapon of destruction to a range of at least 16 miles] or related materiel, including spare parts….” The Security Council can waive the restrictions on a “case-by-case basis,” but no Iran arms transfers have been approved to date. The arms transfer ban expires on the earlier of: (1) five years after the JCPOA “Adoption Day” (Adoption Day was October 18, 2015), or (2) upon the issuing by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of a “Broader Conclusion” that all nuclear material in Iran remains in peaceful activities.

U.S. and other Security Council member officials interpret the restriction as inapplicable to the sale to Iran of purely defensive systems. In 2007, Russia agreed to the sale to Iran of the S-300 air defense system, and it delivered the system in November 2016. A State Department spokesperson said in May 2016 that the sale “… is not formally a violation [of 2231]” because the S-300 is for defensive uses only.”

Effects of the Ban

The U.S. government has assessed the arms transfer ban as effective. According to Appendix J of the congressionally mandated Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) annual report on the military power of Iran for 2019, released in November 2019, states that Iran wants to “purchase new advanced weapon systems from foreign suppliers to modernize its armed forces, including equipment it has largely been unable to acquire for decades.”

By contrast, the ban on Iranian arms exports has arguably not been effective. According to the DIA report, which represents a consensus U.S. judgment, “Since the Islamic Revolution, Iran has transferred a wide range of weapons and military equipment to state and non-state actors, including designated terrorist organizations.… Although some Iranian shipments have been interdicted, Tehran is often able to get high-priority arms transfers to its customers. [See Figure 1.] Over the years, Iranian transfers to state and non-state actors have included communications equipment; small arms—such as assault rifles, sniper rifles, machine guns, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs)—and ammunition; … artillery systems, including MRLs (multiple rocket launchers) and battlefield rockets and launchers; armored vehicles; FAC (fast attack craft); equipment for unmanned explosives boats; … SAMs (surface-to-air missiles); UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) … ground-attack aircraft …” and other weaponry. A June 2020 report by the UN Secretary General on implementation of Resolution 2231 assessed that Iran attempted to export weaponry and missile parts to Houthi forces in Yemen, and U.S. and allied forces intercepted some of that weaponry in November 2019 and February 2020.

Relevant Laws, Authorities, and Options for the Administration and Congress

The stated Iran policy of the Trump Administration is to apply “maximum pressure” on Iran’s economy, through the imposition of U.S. sanctions, to compel Iran to alter its behavior. The Administration cited the expiration of the arms transfer ban as one among several reasons that the JCPOA was sufficiently flawed to justify a U.S. exit from the accord in May 2018. As part of the maximum pressure campaign, the Administration insisted on keeping the arms transfer ban in place. At a meeting of the UN Security Council on June 30, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated: “Don’t just take it from the United States, listen to countries in the region. From Israel to the Gulf, countries in the Middle East – who are most exposed to Iran’s predations – are speaking with one voice: Extend the arms embargo.” A May 4, 2020, House letter, signed by 387 Members, “urge[s] increased diplomatic action by the United States to renew the expiring United Nations arms embargo against Iran….”

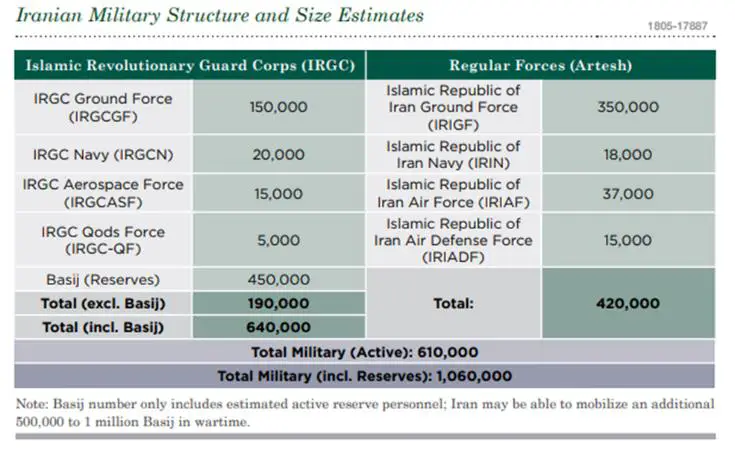

The annual Iran military report, cited above, states: “Iran’s potential acquisitions after the lifting of UNSCR 2231 restrictions include Russian Su-30 fighters, Yak-130 trainers, and T-90 MBTs (main battle tanks). Iran has also shown interest in acquiring S-400 air defense systems and Bastian coastal defense systems from Russia.” On June 23, 2020, Secretary Pompeo posted a Twitter message that: “If the UN Arms Embargo on Iran expires in October, Iran will be able to buy new fighter aircraft like Russia’s SU-30 and China’s J-10. With these highly lethal aircraft, Europe and Asia could be in Iran’s crosshairs.” The composition of Iran’s forces is depicted in below.

In August 2020, the United States circulated a draft UN Security Council resolution that would extend the arms transfer ban “until the Security Council decides otherwise.” Several Council members, including those in Europe, stated opposition to extending, arguing that doing so might cause Iran to leave the JCPOA entirely. Regional U.S. allies, including Israel and the Arab monarchy states of the Persian Gulf, publicly supported the proposed extension

On August 14, the Security Council completed the voting process on the U.S. extension draft. The United States and the Dominican Republic voted in favor, Russia and China voted against, and the remaining eleven Council members abstained. Secretary of State Pompeo immediately denounced the adverse UN vote, saying “The Security Council’s failure to act decisively in defense of international peace and security is inexcusable.” President Trump stated that the United States would proceed to implement its threat to invoke a snap back of all UN sanctions that were lifted upon implementation of the JCPOA if the arms embargo were not extended. He said “We’ll be doing a snapback. You’ll be watching it next week.”

The U.S. plan to trigger a sanctions snap back is based on a State Department legal interpretation of Resolution 21231. According to U.S. officials, Resolution 2231 stipulates that a JCPOA participant could, after notifying the Security Council of an issue that the government “believes constitutes significant non-performance of [JCPOA] commitments,” trigger an automatic draft resolution keeping sanctions relief in effect. A U.S. veto of this resolution would reimpose the suspended sanctions. On April 30, 2020, the then-State Department Special Representative for Iran, Ambassador Brian Hook, asserted that this option is available because the U.S. right “as a participant [in Resolution 2231] is something which exists independently of the JCPOA.”

However, European, Iranian, Russian, and other officials have opposed the U.S. assertion that it can trigger a snapback. On August 16, EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said: “Given that the US unilaterally withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018 and has not participated in any JCPOA structures or activities subsequently, the US cannot be considered as a JCPOA participant. We therefore consider that the U.S. is not in a position to resort to mechanisms reserved for JCPOA participants [such as the so-called snapback].” Despite the dispute over the U.S. standing to trigger a snap back, Secretary of State Pompeo reportedly planned to meet on August 20 with the representative of the current Security Council president – Indonesia – to proceed with the process of snapping back JCPOA sanctions. It is not clear what entity or person might adjudicate the dispute over the U.S standing to do so, and it is not clear that a reimposition of sanctions would obtain broad international implementation

If the United States is not able to snap back sanctions, including the ban, the Administration might use its sanctions authorities to deter any arms sales to Iran. These include the Iran-Iraq Arms Non-Proliferation Act, the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act (INKSNA), Executive Order 13382, the Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act, and Iran’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism provides authorities for the President to sanction arms suppliers to Iran. Alternatively, the United States might try to work with potential arms sellers to Iran to dissuade them from completing any sales.

Sources: Noa Landau, “Iran Arms Embargo: The Quiet Battle of Superpowers Could Shake the UN,” Haaretz, (August 6, 2020);

Michael Schwirtz, “U.N. Security Council Rejects U.S. Proposal to Extend Arms Embargo on Iran,” New York Times, (August 14, 2020);

Courtney McBride and Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. Risks Diplomatic Isolation With Bid to Reimpose U.N. Sanctions on Iran,” Wall Street Journal, (August 19, 2020);

Lara Jakes, “U.S. Heads to United Nations to Demand ‘Snapback’ of Sanctions Against Iran,” New York Times, (August 19, 2020);

Robbie Gramer and Jack Detsch, with Chloe Hadavas, “U.N. Showdown Looms Over U.S. Iran Strategy,” Foreign Policy, (August 20, 2020);

Kenneth Katzman, “UN Ban on Iran Arms Transfers,” Congressional Research Service, (August 19, 2020).