Holy Words

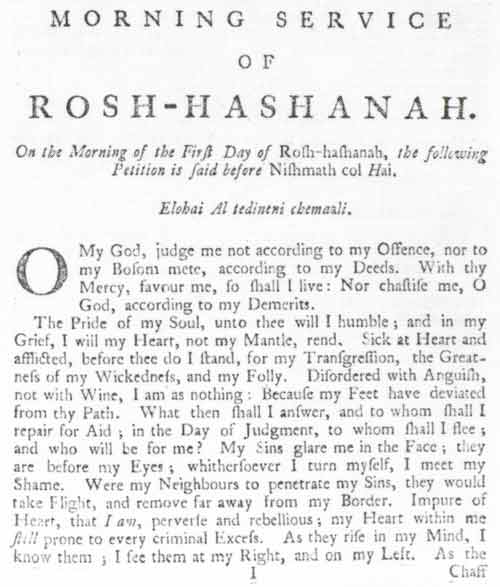

In 1766 there appeared in New York a prayer book

entirely in English, Prayers for Sabbath, Rosh-Hashanah, and Kippur, or

The Sabbath, the Beginning of the Year, and the Day of Atonement . . .

According to the Order of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, translated

by Isaac Pinto, and “for him printed by John Holt in New York A.m.

5526.” Excepting only a fifty-two-page Evening Service of

Roshashanah, and Kippur, published five years earlier in New York, it

is the first published translation of the liturgy into English for synagogue use. The 1761 Evening Service lists neither translator, nor reason

for the translation, but in this volume, Pinto, who was the translator of

both, explains:

[Hebrew] being imperfectly understood by many, by some,

not at all; it has been necessary to translate our Prayers, in the Language

of the Country wherein it hath pleased the divine Providence to appoint our

Lot. In Europe, the Spanish and Portuguese Jews have a Translation in

Spanish, which as they generally understand, may be sufficient, but that

not being the Case in the British Dominions in America, has induced me to

attempt a Translation in English.

The first Jewish liturgical

publication in America was Form of Prayer Performed at Jews Synagogue,

New York, 1760; the second, Evening Service of Rosh-Hashanah and Kippur,

New York 1761; ours, the third, Prayers for Sabbath, Rosh-Hashanah and

Kippur, is the most distinguished for it is a far more substantial work

than the earlier, and because it credits the translator, Isaac Pinto, a

teacher of languages and merchant of New York. It is virtually certain

that he was the translator of the preceding volumes as well. All appeared

before the first prayer book with an English translation was published in

London in 1770. The Library purchased its copy in 1947 for 250 dollars.

Forty years later a copy brought over one hundred times that amount at a

public auction in New York.

Prayers for Sabbath, Rosh-Hashanah and Kippur, translated by Isaac

Pinto, New York, 5526 (1766). Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

|

Not until 1770, four years later, was a prayer book with

an English translation published in London, whose Jewish community was more

than ten times the number of all American Jewry. Acculturation in the New

World was swifter and more complete than in the Old.

Pinto, an English Jew, demonstrated his American loyalty

as a signatory to resolutions favoring the Nonimportation Agreement, one of

America's earliest acts of defiance against England. He was, as Ezra Stiles

describes him, “a learned Jew at New York,” who on his death in

179 1, was extolled in this obituary in a New York newspaper:

Mr. Pinto was truly a moral and social friend. His

conversation was instructive, and his knowledge of mankind was general.

Though of the Hebrew nation, his liberality was not circumscribed by the

limits of that church. He was well versed in several of the foreign

languages. He was a staunch friend at the liberty of his country. His

intimates in his death have lost an instructive and entertaining companion;

his relations, a firm friend; and the literary world, an historian and

philosopher.

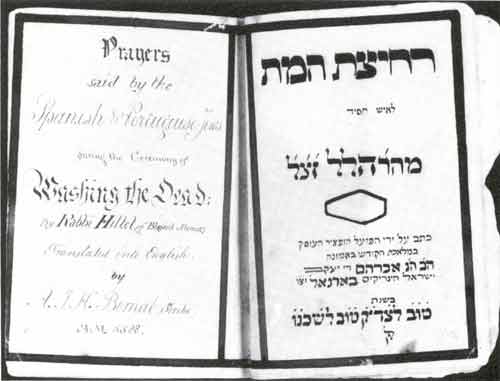

This handbook is to be used

by a member of a Hevra Kadisha (Holy Burial Society), which

prepares the body of the deceased for burial. This manuscript manual

written in Hebrew with an English translation contains both the pertinent

instructions for the proper ritual preparation of the body and the prayers

which accompany it. The scribe, Abraham de Jacob Israel Henriques Bernal,

wrote it in Kingston, Jamaica, for D. K. Da Costa of that community, whose

name appears on the cover. Bernal later served congregations in

Philadelphia and Louisville, Kentucky. It is opened to the double title

page, in Hebrew and English.

Rabbi Hillel, Prayers said by the Spanish and Portuguese Jews during

the Ceremony of Washing the Dead, translated into English by A. 1. H.

Bernal (Scribe), Kingston, Jamaica, 5588 (1828). Hebraic Section.

|

In 1828, acculturation had made such progress in the New

World that Abraham Israel Henriques Bernal, a religious functionary,

teacher and scribe, found it necessary to translate into English the

Prayers said by the Spanish and Portuguese Jews during the Ceremony of

Washing the Dead by Rabbi Hillel of Blessed Memory. A small delicately

written manuscript in Hebrew and English, it contains not only the prayers

to be recited by the Hevra Kadisha (Holy Burial Society) but also

instructions for the ritual preparation of the body for burial. Membership

in this society was traditionally reserved for learned, pious, and

respected members of the community, so that if a translation of the

instructions and the liturgy was needed, it speaks of the poor state of

Jewish knowledge in the Americas. The manual was written in Kingston,

Jamaica, for D. K. Da Costa, a member of its most distinguished family.

“Abr. of I. H. Bernal” is found among the subscribers of that

city for Isaac Leeser's Instruction

in the Mosaic Religion published in 1830. Bernal later went to the

United States and in 1847 was the Hebrew teacher of Congregation Mikveh

Israel in Philadelphia, and three years later was employed as a religious

functionary of the Louisville, Kentucky, congregation.

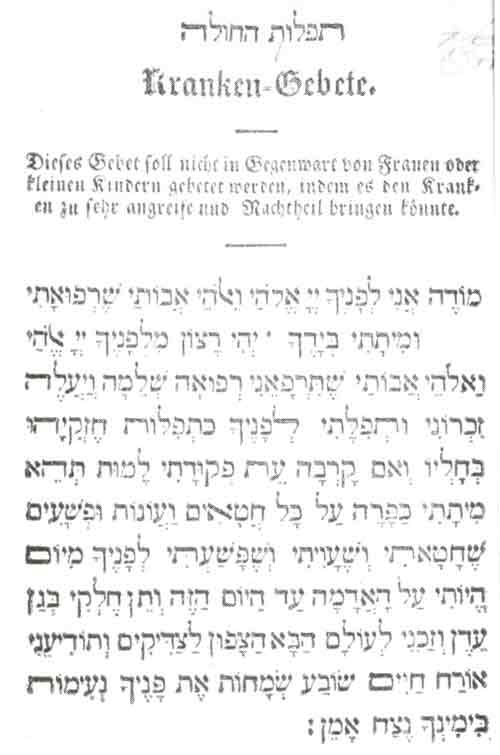

A collection of prayers to be

said by those seeking healing was published in New York (in Hebrew wit

instructions in German) by the Hevra Ahim Rahamim (Society of the

Brothers of Mercy), organized in 1851. Open to a prayer asking God to

“send full healing” or a place in paradise. The German

instruction warns that this petition must not be said in the presence of

women or small children for this could cause too great distress.

T'filat ha-Holeh, Kranken Gebete (Prayers for the Sick), New York,

1854. Hebraic Section.

|

A small pamphlet, Kranken Gebete (Prayers for the

Sick), in Hebrew with instructions in German, issued by the Society of the

Brothers of Mercy in New York in 1854, is among the rarest of American

Jewish liturgical publications. A prayer, to be said by the sick person

himself, carries with it the warning, “This prayer should not be

pronounced in the presence of women or small children, for it may so upset

the sick person as to cause him injury.” it reads in part,

I acknowledge before you, my God, and God of my fathers,

that my healing and my death are in your hand. May it be thy will that you

send me a full healing, and may my prayer rise before you as the prayer of

King Hezekiah in his illness. But if my time has come, let my death serve

as an atonement for all my sins and transgressions ... from the time I was

placed upon the earth to the present day. May my place be Paradise and make

me worthy of the World to Come which is reserved for thy righteous ... Amen

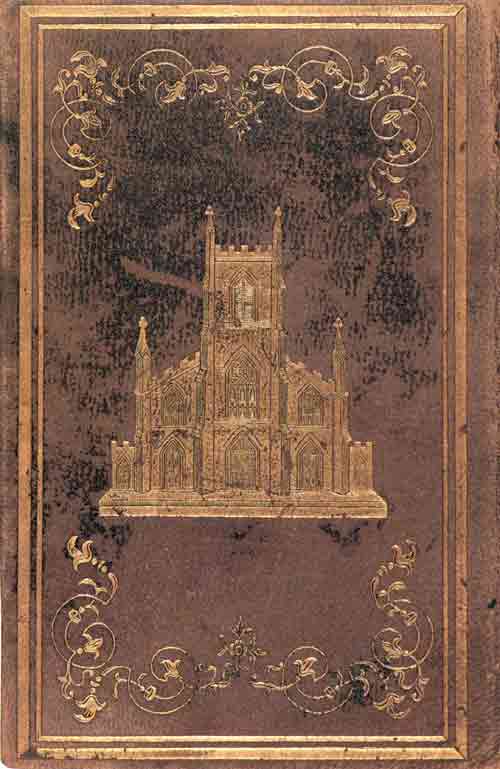

The prayer book prepared for

and published by Temple Emanuel, New York, appropriately has the temple

embossed in gold on its front cover.

Seder T'fillah, The Order of Prayer for Divine Service, revised by

Dr. L. Merzbacher, Rabbi of the Temple Emanuel, 1855; second edition,

revised by Dr. S. Adler, New York, 1863. Hebraic Section.

|

Three Reform prayer

books appeared in the 1850s, each more radical than its predecessor. The

first, Order of Prayer for Divine Service, Revised by Dr Leo Merzbacher (1810-1856), “Rabbi at the Temple Emanu-el'' of New York, was

published in that city in 1855. Though prepared for one of the first and

leading Reform congregations in America, it is an abridged form of the

traditional prayer book, with Hebrew text and facing English translation,

and it is paginated from right to left. The Kol Nidre prayer is omitted,

but the five services for the Day of

Atonement are retained, as is the prayer for restoration of the dead,

“who revivest the dead ... and killest and restorest to life.“

Because it departed from tradition, it could not be used in traditional

congregations; and because its revisions were slight it was not adopted by

Reform congregations either, so very few copies, especially of volume 1,

have survived.

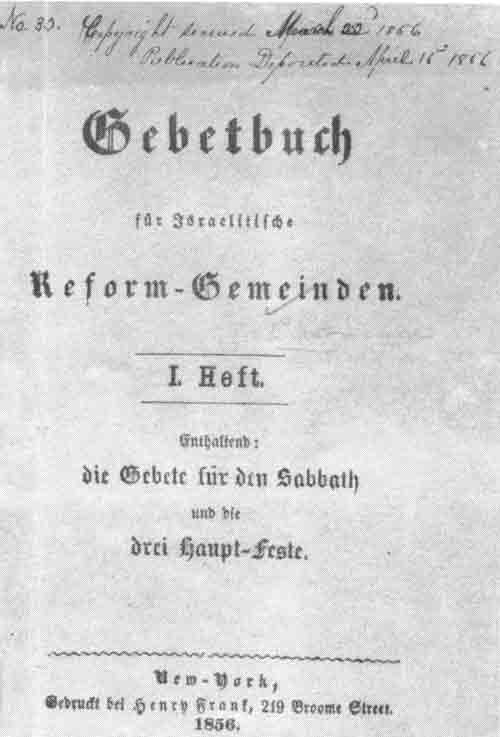

A pamphlet of prayers

prepared by Rabbi David Einhorn for his Har Sinai Congregation, Baltimore.

Unlike the prayer book which Merzbacher prepared for Temple Emanuel a year

earlier, which is an abridgement and revision of the traditional Hebrew

prayer book, the liturgy of Einhorn is a radical departure. Its language

of worship is both German and Hebrew, and it is paginated from left to

right. The complete text was published two years later in 1858, as Olat

Tamid.

Gebetbuch fur Israelitische Reform Gemeinden, I. Heft, New York,

1856. Hebraic Section.

|

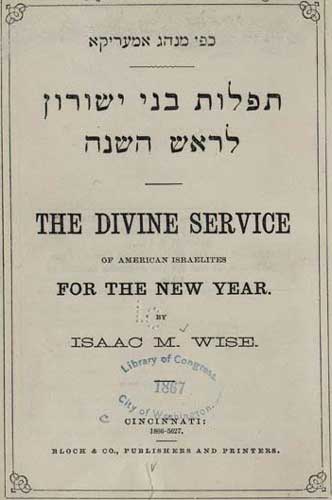

In 1846, Isaac

Mayer Wise began to plan a new prayer book which

was to be a liturgy appropriate to the American scene,

for as he explained in the Occident (vol. 5, p. 109) “the strength of Israel is divided,

because the emigrant brings his own Minhag [liturgical

rite] from his home.” He argued that “such a cause

for dissension would be obviated by a Minhag America.” Ten years later, the projected prayer

book was published in Cincinnati in two versions, the

Hebrew text plus an English or a German translation,

the Hebrew paginated from right to left, the vernacular

from left to right. The Hebrew title is Minhag America,

T'fillot B'nai Yeshurun (the name of his congregation);

the German, Gebet-Buch fur

den offentlichen Got\tesdienst und die Privat-Andacht (Prayer

Book for Public and Private Worship); and the English,

simply, The Daily Prayers.

The form of the traditional prayer book was retained,

but passages which did not conform to “the wants

and demands of time” were freely

deleted. Thus, where the Merzbacher prayer book has “send

a redeemer to their children's children,” Wise

changes the Hebrew goel (redeemer) to geulah (redemption) and the translation

to read “bringest

redemption to their descendants.” it came to be

known as the Wise Prayer Book, as a fitting tribute

to its architect and fashioner, who saw to its publication

and promoted its distribution.

Isaac M.

Wise (1819-1900). Minhag Amerika [The Divine Service of

American Israelites

for the New Year].

Cincinnati: Bloch, 1866. Hebraic

Section

|

Dr. David Einhorn (1809-1879) was brought to Baltimore

by the Har Sinai Congregation in 1855. A year later the first section of

his Gebetbuch fur Israelitische Reform Gemeinden (Prayer Book for

Jewish Reform Congregations) was published in New York, a radical departure

from the traditional prayer book. The Library's copy is as issued: paper

wraps are preserved, and the cover states, “Copyright secured March

22, 1856, Publication Deposited April 15, 1856.” Its main language is

German, its pagination is from left to right, and its changes are both

substantial and substantive. The traditional rubrics are dispensed with,

and special prayers reflecting more the tenor of the age than the

traditions of the faith are inserted. Two years later, in 1858, the

completed work was published in Baltimore with Olat Tamid (Eternal

Offering) added to its title. The traditional day of mourning for the

destruction of the Temple, Tisha b'Av, is turned into a day of

commemoration and consecration:

The one Temple in Jerusalem sank into the dust, in order

that countless temples might arise to thy honor and glory all over the wide

surface of the globe.

When Reform Judaism shaped its first official prayer

book, The Union Prayer Book, the model chosen was Einhorn's Olat

Tamid.

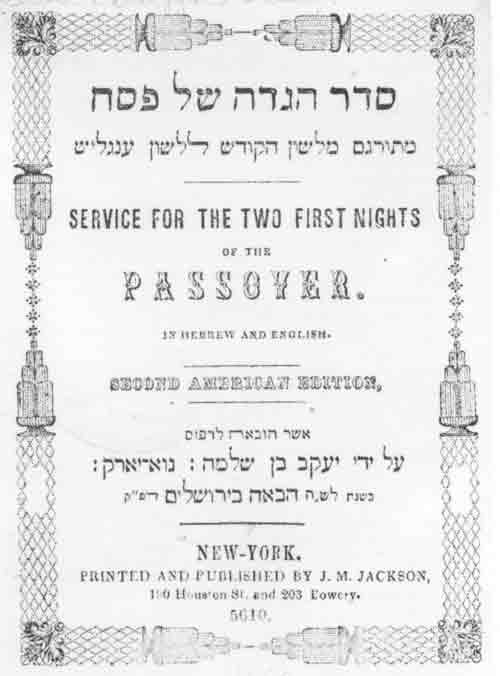

The first American edition of

the Passover Haggadah was published by Solomon Henry Jackson in New York

in 1837. it is fitting that this second American edition be the

publication of his son John M. Jackson, who succeeded his father as the

Hebrew and English printer for New York's Jewish community. On the back

cover Jackson announces that he can supply blank ketuboth (marriage

contracts) printed to order “on parchment if required” and a

family and pocket luach (calendar), and boasts that his prices are

“as cheap as the cheapest!”.

Seder Haggadah shel Pesah (Service for the Two First Nights of the

Passover), second American edition, New York, 5610 (1850). Hebraic

Section.

|

The Haggadah marked “Second American Edition”

is, in a sense, the first. The first edition, so identified by its

publisher S. H. Jackson, was printed in New York in 1837, and on both

Hebrew and English title pages reads, “Translated into English by the

late David Levy of London.” No such attribution to a foreign source is

found on his son's edition, which appeared in 1850, where the only credit

noted is to the printer and publisher, J. M. Jackson, 190 Houston Street

and 203 Bowery. The Hebrew chronogram on both reads “Next Year in

Jerusalem.”

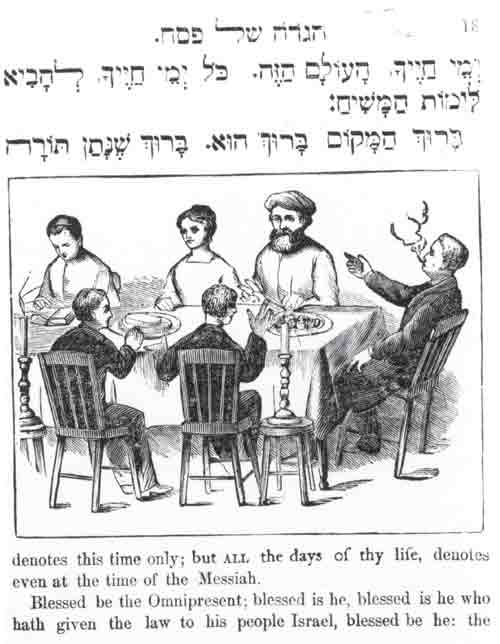

A truly American note is found in a Haggadah published

in New York in 1878. The text is traditional, the translation usual, but

the seder table scene is new. It shows a turbaned father and a prim mother

with the wise son, a kippah (skullcap) on his head and reading from a book, at their side. Across from

them, the simple son sits bareheaded, as does the one “who knows not

how to ask,” while the wicked son, bareheaded, is leaning back on his

chair, smoking a cigarette. Haggadah illustration is commentary.

Although the title page

claims in large bold capital letters WITH NEW ILLUSTRATIONS, the only new

one is the one shown here. An American family at the Seder table presents

a new version of the depiction of the “four sons” described in

the Haggadah. The wise son, kippah (skull cap) on head, is looking at that

Haggadah before him; the simple son, or the backward one, is thumbing his

nose and getting his finger burned by the candle; and the wicked son,

bareheaded, his chair tilted back, is smoking a cigarette.

Seder Haggadah L'Pesah (Form and Relation of the Two First Nights

of the Feast of Passover), New York, 1878. Hebraic Section.

|

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress,

1991).

|