Rebuilding Jewish Communities

What came to an early end in Italy was soon taken up in Jewish communities east and north, in Salonica,

Constantinople, Cracow, Lublin, Amsterdam, Frankfurt an der Oder, Frankfurt am Main, Sulzbach, Vienna,

Warsaw, Vilna, Berlin, Munich, and more, as representative volumes and whole sets of the Talmud in the Library

of Congress attest. Let us look at a few.

Exiles from Spain and Portugal made the port city Salonica in the Ottoman Empire a great center of Jewish life

and learning, and of Hebrew printing as well. Among the early printers were the brothers Solomon and Joseph

Jabez, who began to publish in 1543. All manner of calamities befell the brothers, including fires and plagues,

but they pressed on with their "holy labors." For a while they sought better fortune in Adrianople, another center

for Iberian exiles, and in Constantinople. Joseph resumed publishing in Salonica, announcing in 1560, "when I

saw that the Talmud was burned, I resolved that it was time to do valiantly for the Lord ... to begin publishing the

Talmud again, if God would grant me life, and generous persons their aid." Only a few volumes were published,

of which the Library has the tractate Hulin (1566). In the 1580s the brothers joined together to publish an edition

of the Talmud in Constantinople. Many of the volumes which appeared have found a home in the Library.

In the sixteenth and in the first half of the seventeenth centuries, Poland was the preeminent Jewish community

on the European continent. in this vibrant community-home to great scholars, flourishing schools of learning, and

a busy press-no less than seven editions of the Talmud were undertaken, of which the Library has a number of

volumes published in Cracow by Isaac Prosnitz, 1602-5, and in Lublin by Abraham Jaffe in 1619. An edition of

the Palestinian Talmud was published in Cracow in 1609 "under the sovereignty of the great King Sigmund III,

may his glory be elevated, by Isaac the son of Aaron of blessed memory of the community of Prosnitz. Out of my

straits I have called upon the Lord; He answered me with abundant salvation. The Lord is my helper, I will yet

see the [defeat] of my enemies." (Psalms 118:5, 7) Forty years later, the Jews of Poland called out unto the Lord,

but there was neither saving nor victory. The Ukrainian rebellion against their Polish oppressor, led by Bogdan

Chmielnicki, wrought havoc with Polish Jewry in 1648-49, decimating some seven hundred communities and

destroying uncounted books. The books which survived are few and precious. Even in the midst of destruction, in

1648, the publisher Solomon Zalman Jaffe, his press having been previously ravaged by fire, took up the work

again to publish a Lamentation on the Dread Decrees of 1648 by the noted scholar, Yom Tov Lipmann Heller.

By 1665, printing began again, on poor paper and with roughly cut type. The Library has an imperfect copy of the

first book off the press, Pelah ha-Rimon, set in type by Sarah Jaffe, the wife of the printer.

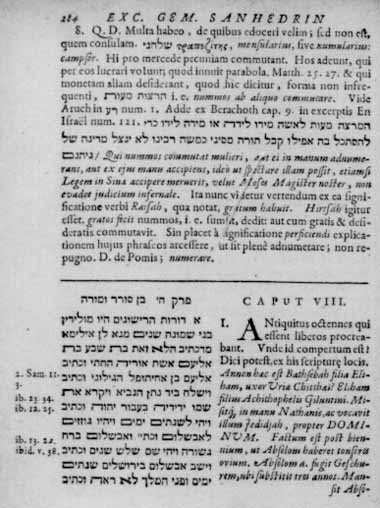

Johannes Koch (1603-1669), Dutch Christian Bible scholar and orientalist, professor of theology at Leyden, published his Latin translation for the Mishnah of tractates Sanhedrin and Maccoth with a commentary, when he was only twenty-six years old. Two poems in fine Hebrew, by John Persius of Amsterdam and a student, Henry Martinus of Bremen, extolling the translator, indicate the extent and quality of Hebrew studies among Christians in the early seventeenth century (Johannes Coccejus, Duo Tituli Thahnudici Sanhedrin et Maccoth, Amsterdam, 1629. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

A full set of the first Amsterdam edition of the Talmud, printed by Immanuel Benveniste, 1644-47, is the first in

a run of complete editions of the Talmud in the Library's collection. Although this edition was esteemed because

passages expunged by censorship in previous editions were now restored, its relatively small size made it

difficult to read-for all pages of all editions of the Talmud were uniform in text from 1520 on; the only way to fit

all the text on the smaller page was to reduce the size of the type. So, soon after its publication it became

necessary to reduce the price drastically, making this the first Hebrew published work to be "remaindered." Later,

however, it gained popularity precisely because its smaller size made it easier to handle, store, and carry.

Publishers in Amsterdam, Metz, and Offenbach subsequently solved the problem of the uniform page by dividing

the page and printing it on two pages, yet retaining the standard pagination. This made it possible to have a

relatively small volume with large type. The Library has a number of such half-page volumes of various tractates

of the Talmud.

Half a century later, an edition published in Frankfurt an der Oder had grand size and great aesthetic distinction.

The printer was a Christian, Michael Gottschalk; the publisher was Professor John Christopher Beckman, who

received special permission for its publication from Duke Frederick 111, Elector of Brandenburg. Publication

was financed by the "court Jew," Behrend Lehmann, whose Hebrew name was Issakar Berman Segal of

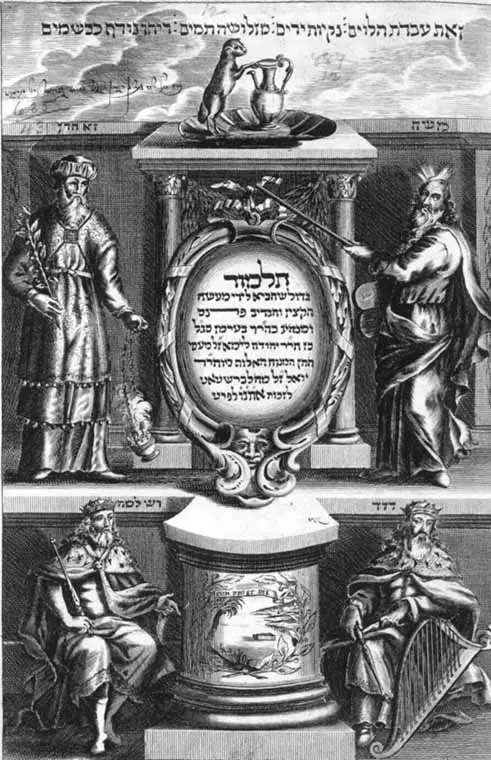

Halberstadt. Each of the twelve volumes has an engraved title page by M. Bernigeroth, showing Moses, Aaron,

David, and Solomon, the first two flanking a tribute to the benefactor. Although each title page bears the claim

that this edition is like "the one printed in Basle," a heavily censored one, many previously expurgated passages

are restored, and where deletions are retained, blank spaces are left to indicate the omission to the reader and, no

doubt, to permit him to fill in by pen what they dared not print. The formerly deleted tractate Avodah Zara (Idolatry) is now included as well, to give further integrity to the published text.

One of the finest editions of the Talmud was this, published in Frankfurt an der Oder in 1697. Moses and Aaron, David and Solomon frame the inscription on the engraved title page which states that it was made possible by the generosity of Berman Segal of Halberstadt. A "Court Jew," he provided 50,000 Rhenish Thaler to make possible its publication and distribution to institutions and scholars in Germany and Polish Jewish communities devastated by the seventeenth-century wars and their aftermath. The owner's inscription is that of "Isaachar, the son of the great Gaon, our rabbi and teacher, Gabriel of Cracow (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

The purpose of the edition was both utilitarian and aesthetic, as is stated in approvals granted by leading rabbis

for its publication. The Thirty Years War (1618-1648) devastated German Jewry, the Uprising of 1648-49 and

the Swedish-Russian War which followed all but destroyed Polish Jewry. Wars over, it was time to rebuild.

Scholars and schools needed the Talmud for study, and the spirit of German and Polish Jewry would be uplifted

by a new edition which would surpass previous ones in grandeur. As Rabbi Moshe Yehudah, the son of Rabbi

Kalonymos Cohen of Amsterdam's Ashkenazi Jewry, wrote in his approbation for the publication of this edition:

The worthy Issakar Berman ... resolved to produce a Talmud of equal quality and worth as the earlier editions of

Cracow and Lublin, and certainly superior to the edition which appeared in Amsterdam in very small type and

unclear print.

The need was attested to by Rabbi Naftali ben Yitzhak Katz of Posen in his approbation:

Our world had turned into void and desolation. Twenty men had to use one Talmud. Each day the holy books

grew fewer in number. We faced the danger that the Torah, heaven forfend, would be forgotten. There was no

hope and no means to have the Talmud reprinted.

And as Rabbi Josef Shmuel of Cracow, Rabbi of Frankfurt am Main, reported in approving its publication:

There was no more than one copy of the Talmud in a city. Many tried to reprint it but failed, until God inspired

the prince and leader, Reb Berman of Halberstadt ... for the honor of the Torah to print the Talmud on fine paper

and good type, and engage good scholars to supervise the work to guard against mistakes or corruption of the

text.(*)

A Swedish visitor to Frankfurt, Olaf Celsius, reported that he saw seven printers busily engaged in setting type,

page by page, of tractate Nazir, and "a Jewish girl sat there too, and reached the third chapter of Baba Kama." The girl was eleven-year-old Ella, who together with her brother is credited at the end of tractate Nidah with

having set the type. In his history of the Jewish community of Halberstadt, B. H. Auerbach states that the

generous patron provided 50,000 Rhenish Thaler for the 5,000-copy edition, half of which was distributed to

scholars who could not afford to purchase it. It was a truly magnificent edition, in typography, adornment and

integrity of text, and in the generosity of Behrend Lehmann, who used a substantial portion of his hard-earned

fortune for the benefit of his faith and the uplift of his people.

*Almost all Hebrew printed books inserted approbations of distinguished rabbis approving their publication. These serve as a copyright for they generally forbade the work's replication for a stated number of years.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress,

1991).

|