Charting the Holy Land: Holy Jerusalem

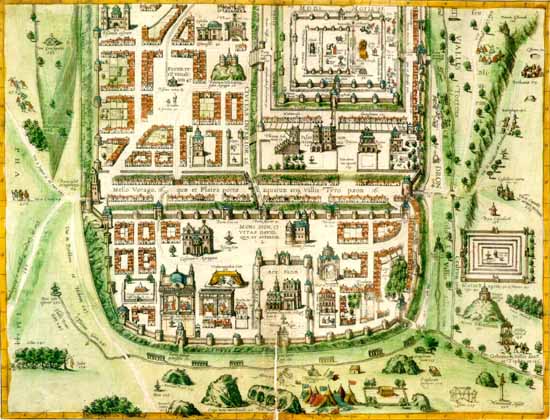

The greatest early cartographic-artistic representational map of Jerusalem is that of Christian von Andrichom (1533-1585). George Braun and Franciscus Hogenberg adapted it for inclusion in their monumental Civitates Orbis Terrarum published in six volumes between 1572 and 1617. It has rightly been called the most impressive and elaborate collection of city views ever produced. Jerusalem is accorded two consecutive sheets, which show the city as it was conceived to be in the time of Jesus. A wall encloses a well laid out metropolis with imposing buildings, wide avenues, and spacious plazas and verdant surroundings; in short, a model medieval European city whose anachronistic character gave to the viewer a sense of immediacy and comfortable familiarity. The seventeenth- and eighteenth-century viewer could "walk its streets" and vicariously experience those momentous events which took place there and so radically altered human history.

The finest early artistic map of Jerusalem architecturally depicted is Christian von Andrichom's double-page plate in Braun and Hogenberg's atlas of the great cities of the world, Civitates Orbis Terrarum. Shown is the lower plate which depicts the Temple of Solomon, the City of David, Mt. Zion, all in contemporary sixteenth-century architecture, (George Braun and Franciscus Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, vol. 4, Cologne, 1612. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress Photo).

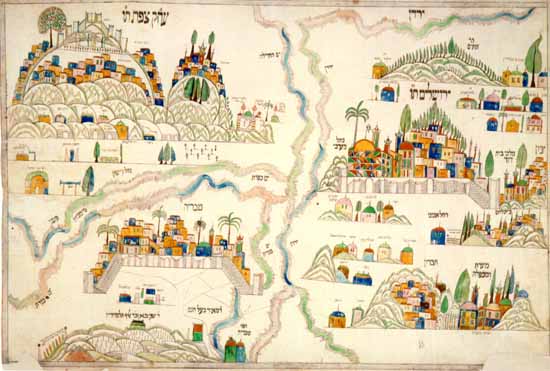

Jerusalem was and remains the holiest of cities in the Holy Land, but Jews also gave a measure of holiness to three other cities there: Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. The holiness of Jerusalem arises in part from what remains there, but more from what took place there. So it is with its sister cities. Hebron is where the patriarchs and matriarchs lived and are buried, and it was the first capital of King David. Tiberias, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, was chosen by the patriarch of the Jews in the second century as his seat. The Palestinian Talmud was largely composed in its great rabbinical academy. in the environs of Safed, high in the Galilean hills, are the graves of the leading rabbis of late antiquity. Its stature as a holy city was enhanced in the sixteenth century, when it was the greatest center of Jewish mysticism and seat of Jewish legal scholarship. To gain entree into the company of the three more ancient holy cities, it called itself Beth-El, suggesting identity with the biblical site which Jacob called "The Gate of Heaven."

This charming pastel watercolor wall plaque depicting the holy cities of the Holy Land-Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias, and Safed-was painted in Palestine in the second half of the nineteenth century. The depiction is neither geographic nor topographic but religio-historical, presenting this holy venue not as it existed on earth but as envisioned by a pious resident or pilgrim who was a gifted primitive artist, ("Holy Cities" Wall Plaque, Pastel Watercolor, Jerusalem (?), c. 1870. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

A striking pastel-colored manuscript "holy site map" links these four holy cities together. Drawn and painted in Palestine in the second half of the nineteenth century, it depicts those venues which indicate their holiness. There is a suggestion of their geographic positioning, but the "map" is far more a statement of the place these cities hold in Jewish veneration, than of the geographical site they occupy. To pious Jewish families, such wall plaques were more meaningful depictions of the Holy Land than the most aesthetically beautiful and topographically exact representations.

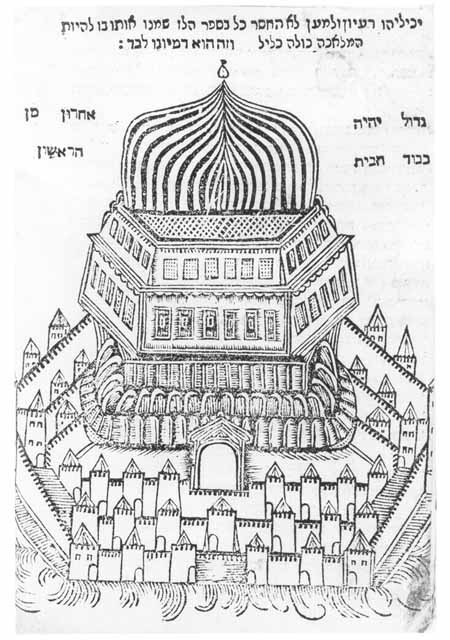

A small illustrated guide book to the burial places of biblical figures and saintly rabbis in the Holy Land, Zikaron Birushalayim, appeared in Constantinople in 1743. It tells the pious pilgrim where graves may be found and what prayers are to be said. Prefaced by a panegyric to the land, it cites a midrashic statement that, in time to come, when Jerusalem shall be rebuilt, three walls-one of silver, one of gold, and the innermost of multicolored precious stones-will encompass the dazzling city.

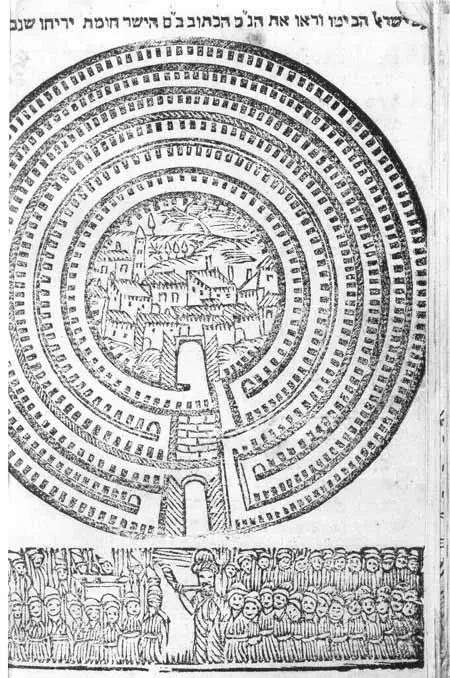

Two woodcut depictions of Holy Land sites: the first of the Temple in Jerusalem, and the second (below) of Jericho, with Joshua and the Children of Israel positioned outside the city walls, (Zikaron Birushalayim (Remembrance of Jerusalem), Constantinople, 1743. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

In Hebron the pilgrim is not only directed to the holy grave sites, but also regaled with wondrous tales. One tells of a sexton of the community sent down to search for a ring which had fallen to the depths of the patriarchs' burial cave, finding at the floor of the cave three ancient men seated on chairs, engaged in study. He greets them; they return his greetings, give him the ring, and instruct him not to disclose what he had learned. When he ascended and was asked what he had seen, he replied: "Three elders sitting on chairs. As for the rest, I am not permitted to tell."

For actual pilgrims, the little volume provided factual information. For pilgrims in their own imagination, it offered edification through tales and quaint illustrations. The last page has a woodcut of Jericho, a seven-walled city, below which a man surrounded by a multitude is sounding a shofar. The most striking woodcut is of an imposing building, representing the Temple in Jerusalem.

In the concentric circles of holiness cited in the Tanhuma, Jerusalem is at the center of the Holy Land; the Temple at the center of Jerusalem; and the Holy of Holies at the center of the Holy Temple. The Temple is prominently featured in illustrated books about the Holy Land. In A Pisgah-Sight of Palestine, three chapters describe and three engravings portray the Temple. Early Hebrew books are quite poor in illustrations, because relatively few deal with subjects that demand visual presentation.

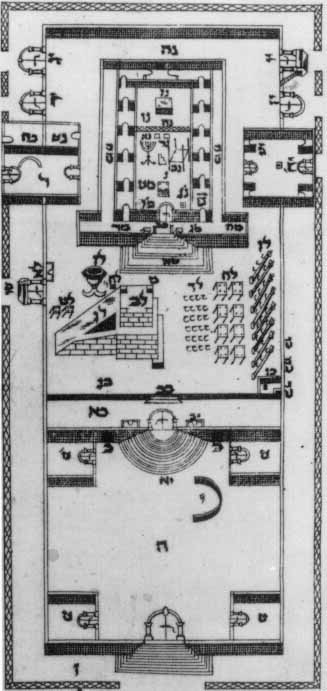

Among these are books dealing with laws concerning the Temple, and since its architecture and vessels are pertinent to the laws, they invite illustration. A case in point is Sefer Hanukat Ha-Bayit by Moses (Hefez) Gentili (1663-1711), published in Venice in 1696. A treatise on the building of the Second Temple, it abounds in engraved architectural illustrations, including a menorah, the seven-branched candlestick; most notable is a large pull-out map of the Temple, identifying fifty-eight components of the Temple's structure. The engravings were added after the printing, as was the map, and a copy containing both is rare.

In the gradations of holiness of space, the Holy Land is the holiest of lands, Jerusalem the holiest of cities, and its holiest place is the Temple Mount, whose holiest spot is the Holy of Holies in the Temple itself. Among the architectural engravings in this work on the Temple is a pullout map of the Temple, identifying its component parts. The Holy of Holies is the uppermost square room, (Moses Gentili, Sefer Hanukat ha-Bayit, Venice, 1696. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

Moses Gentili, born in Trieste, lived in Venice where he taught Talmud and Midrash, and perhaps philosophy and science as well. His best-known work, Melekhet Mahashevet, Venice, 1710, a commentary on the Pentateuch, contains a picture of the author, a clean-shaven, ministerial-looking gentleman.

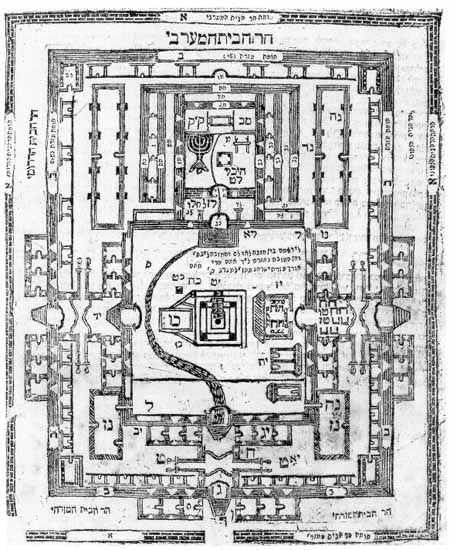

Yom Tov Lipmann Heller's description of the Temple, "the future Temple as envisioned by the prophet Ezekiel," Zurat Beit ha-Mikdash, was first published in Prague, 1702. For this Grodno, 1789 edition, Moses, Ivier added illustrations, notably this architectural map of the "once and future Temple." It is similar to, yet different from the depiction by Gentili, (Yom Tov Lipmann Heller, Zurat Beit ha-Mikdash (The Form of the Temple), Grodno, 1789. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

There are many published descriptions and illustrations of the Temple's appearance in many languages. Some are based on careful study of the available sources, others are creations of the imagination, generally inspired by the grandest building the artist knew. A plan of the Temple to be is found at the end of the 1789 Grodno edition of Zurat Beit Ha-Mikdash (The Form of the Holy Temple) by Yom Tov Lipmann Heller (1579-1654), one of the major figures in Jewish scholarship in the first half of the seventeenth century. The book is one of Heller's earliest works and is a projection of the plan of the Temple as envisaged in the prophecy of Ezekiel.

We have thus traversed the Holy Land and glimpsed its holy places, past, present, and future.

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991).