The First Hebrew Book?

The crown jewel of a great Hebraic collection

would, of course, be the first Hebrew book printed. For that we must

go to Italy, the cradle of Hebrew printing, only Spain, Portugal, and

Turkey sharing its distinction of having produced Hebrew incunabula

(books printed before the end of the fifteenth century). It is

generally agreed by students of Hebrew typography that a group of

books known as the Rome incunabula were the first Hebrew books

printed.

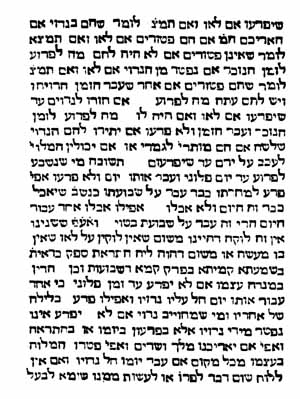

The Rome Incunabula, eight-perhaps nine-in number,

bear no date or place of publication; however, it is widely accepted

that six of these were printed between 1469 and 1472. One, the Commentary

on the Pentateuch of Moses

ben Nahman (Nachmanides) (1194-1270), has the names of the

printers, three in number, "from Rome," but not in or of

Rome. There is far stronger documentary evidence that another, a

collection of Responsa by Solomon ben Adret, was published in Rome.

This was established in 1896 by Rabbi David Simonsen, Chief Rabbi of

Denmark and a noted bibliophile, who pointed out a reference (in a

pamphlet published in Venice in 1566) to the responsa of Solomon ben

Abraham Adret (Rashba) of Barcelona (c. 1235-c. 1310), published

"in Rome," a reference that could fit only the Rome

incunabulum bearing that name: Teshuvot She'elot ha-Rashba (The Responsa of Adret). The Library of Congress has a copy of this

volume, as well as a fourteenth-century manuscript containing thirty

responsa of Adret. In his definitive work on these incunabula, Moses

Marx explains their "primitive" typography as an indication

of their antiquity and proposes "proof" that the Commentary

of Nachmanides was probably the first one printed. His point is well

taken, but the type of the Adret volume looks no less primitive,

being bolder and less refined. It is also slightly larger, which

would argue for its earlier date, since the high cost of paper at the

birth of printing would suggest that smaller type, using less paper,

would be a desired later improvement. Might we then not claim that,

as the only volume which is documented as being printed in Rome, the

one whose typography is larger and more primitive is therefore the

one that may most justifiably be called the first printed Hebrew

book?

|

|

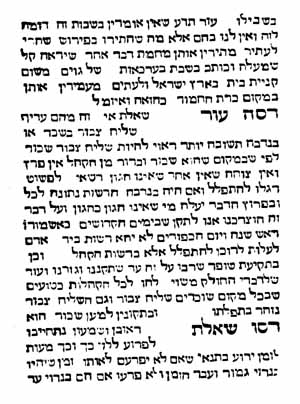

There is no agreement as to which was the first

Hebrew book printed, but there is general agreement that it was one

of a group printed, without place or date of publication, in Rome

between 1469 and 1472. Among these is this volume of Responsa by the

most prolific of respondents, the Rashba, i.e., Solomon ben

Abraham Adret (c. 1235-c. 1310). Our volume is open to responsurn

265, dealing with the question: which is to be preferred, a precentor

who receives remuneration (i.e., a professional cantor), or one who

volunteers his services gratis? The answer: a professional engaged by

the community is to be preferred, so that one unskilled in the art

will not be able "to unfurl his banner" and act the role. (Library

of Congress Photo)

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress, 1991).

|