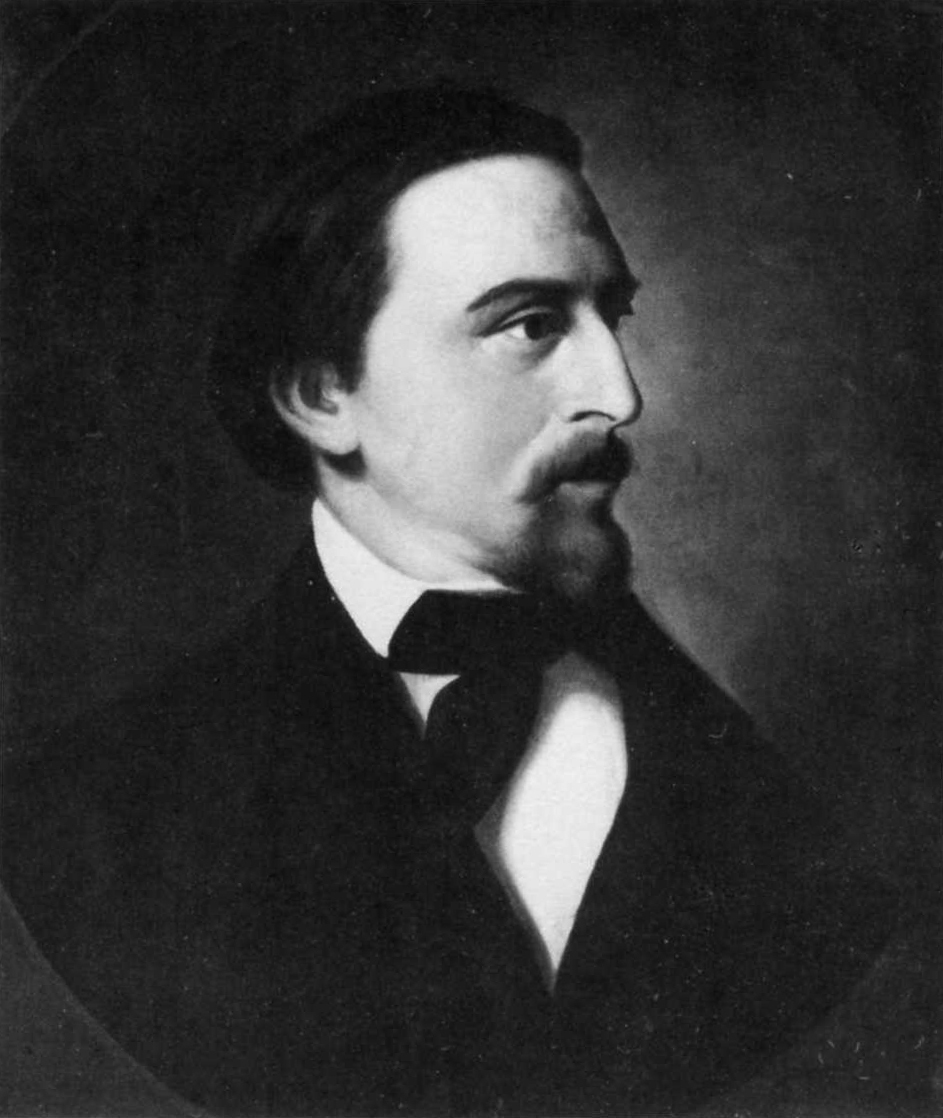

Wilhelm Marr

(1819-1904)

Known as the father of modern anti-Semitism, Wilhelm Marr led the fight to overturn Jewish emancipation in Germany.

Born in 1819, Marr was a Lutheran (not a Jew as sometimes claimed), the son of a famous theater personality.

He entered politics as a democratic revolutionary who favored the emancipation of all oppressed groups, including Jews. He got involved with left-wing exiles in Switzerland, but was expelled from the country in 1843.

He returned to Germany, joining the revolution of 1848 in Hamburg. He became embittered by the failure of the revolution to democratize Germany, and about his own rapidly declining political fortunes. He left for a decade to live in North and Central America.

When he returned to Hamburg, his views had radically changed and he turned his venom against the Jews. His essay “Der Weg zum Siege des Germanenthums uber das Judenthum. (“The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism”) was published in 1862. Marr’s conception of anti-Semitism focused on the supposed racial, as opposed to religious, characteristics of the Jews. His organization, the League of Antisemites, introduced the word “anti-Semite” into the political lexicon and established the first popular political movement based entirely on anti-Jewish beliefs.

That publication attracted little attention, but he produced a bestseller 17 years later with “The Victory of Judaism over Germandom.” This often-reprinted political tract resonated with the German public at a time when the country was in economic and social turmoil. In it, he warned that “the Jewish spirit and Jewish consciousness have overpowered the world.” He believed that Jews had been engaging in an 1,800-year worldwide conspiracy against non-Jews that was about to succeed. He called for resistance against “this foreign power” before it was too late. Marr thought that before long “there will be absolutely no public office, even the highest one, which the Jews will not have usurped.” For Marr, it was a badge of honor to be called an anti-Semite.

Marr and others employed the word anti-Semitism in the largely secular anti-Jewish political campaigns that became widespread in Europe around the turn of the century. The word derived from an 18th-century analysis of languages that differentiated between those with so-called “Aryan” roots and those with so-called “Semitic” ones. This distinction led, in turn, to the assumption – a false one – that there were corresponding racial groups. Within this framework, Jews became “Semites,” and that designation paved the way for Marr’s new vocabulary. He could have used the conventional German term Judenhass to refer to his hatred of Jews, but that way of speaking carried religious connotations that Marr wanted to de-emphasize in favor of racial ones. Apparently more “scientific,” Marr’s Antisemitismus caught on. Eventually, it became a way of speaking about all the forms of hostility toward Jews throughout history.

Over the centuries, anti-Semitism has taken on different but related forms: religious, political, economic, social, and racial. Jews have been discriminated against, hated, and killed because prejudiced non-Jews believed they belonged to the wrong religion, lacked citizenship qualifications, practiced business improperly, behaved inappropriately, or possessed inferior racial characteristics. These forms of anti-Semitism, but especially the racial one, all played key parts in the Holocaust.

Importantly, Hitler and his followers were not anti-Semites primarily because they were racists. The relation worked more the other way around: Hitler and his followers were racists because they were anti-Semites looking for an anti-Jewish stigma deeper than any religious, economic, or political prejudice alone could provide. For if Jews were found wanting religiously, it was possible for them to convert. If their business practices or political views were somehow inappropriate, changed behavior could, in principle, correct their shortcomings. But anti-Semites in the line that ran from Marr to Hitler believed that Jews were a menace no matter what they did. As Marr put the point, “the Jews are the ‘best citizens’ of this modern, Christian state,” but they were that way, he added, because it was “in perfect harmony with their interests” to be so. Undoubtedly, Marr believed – and Hitler agreed even more so – that the interests of Jews were irreconcilably at odds with Germany’s.

For anti-Semites of Marr’s stripe, converted Jews were still untrustworthy Jews. Jewish behavior might change in any number of ways, but the “logic” of racist anti-Semitism did not consider such changes as reasons to give up anti-Semitism. To the contrary, this anti-Semitism interpreted Jewish assimilation as infiltration, Jewish conformity as duplicity, and Jewish integration into non-Jewish society as proof of Jewish cunning that intended world domination. On the other hand, if Jews insisted on retaining their distinctively Jewish ways, that insistence provided evidence of another kind to show that Jews were an alien people. Added to earlier forms of anti-Semitism, racial theory “explained” why the Jews, no matter what appearances might suggest to the contrary, were a threat that Germans could not afford to tolerate.

Marr failed in his effort to establish an organization dedicated to solving the “Jewish question” and faded into poverty and obscurity. He died in 1904.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

P.W. Massing, Rehearsal for Destruction (1949), 6–10, 211–212; M. Zimmermann, Wilhelm Marr: The Patriarch of Anti-Semitism (1986); R.S. Levy, Antisemitism in the Modern World: An Anthology of Texts (1991), 74–93.

Sources: The Holocaust Chronicle.

Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.