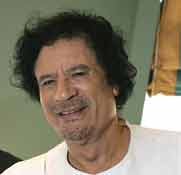

Muammar Gaddafi

(1942 - 2011)

Colonel Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi (June 1942 - October 20, 2011) is best known as the de

facto leader of Libya from 1969 till his death in 2011.

Though Gaddafi did not have an official title or hold a

public office since 1977, he was accorded

the honorifics “Guide of the First

of September Great Revolution of the

Socialist People’s Libyan Arab

Jamahiriya” or “Brotherly

Leader and Guide of the Revolution” in

government statements and the official Libyan

press.

Early life

Gaddafi was the youngest child born into

a peasant family and grew up in the desert

region of Sirte. He was given a traditional

religious primary education and attended

the Sebha preparatory school in Fezzan from

1956 to 1961. Gaddafi and a small group of

friends that he met in this school went on

to form the core leadership of a militant

revolutionary group that would eventually

seize control of the country in the lat 1960's. Gaddafi's inspiration

was Gamal Abdel Nasser, president of neighboring Egypt, who rose to the presidency by appealing

to Arab unity. In 1961, Gaddafi was expelled

from Sebha for his political activism.

Gaddafi went on to study law at the University

of Libya, where he graduated with high grades.

He then entered the Military Academy in Benghazi

in 1963, where he and a few of his fellow

militants organized a secretive group dedicated

to overthrowing the pro-Western Libyan monarchy.

After graduating in 1965, he was sent to

Britain for further training at the British

Army Staff College, now the Joint Services

Command and Staff College, returning in 1966

as a commissioned officer in the Signal Corps.

Military coup d'état

On September 1, 1969, a small group of military

officers led by Gaddafi staged a bloodless

coup d'état against King Idris I,

while he was in Kammena Vourla, an area in

Greece for medical treatment. His nephew

the Crown Prince Hasan as-Senussi was set

to become King on September 2 when the abdication

of King Idris dated August 4 was to take

effect. Before the end of the day

the monarchy was abolished and the Libyan

Arab Republic was proclaimed with the Crown

Prince being placed under house arrest.

Unlike some other military

revolutionaries, Gaddafi did not promote

himself to the rank of general upon seizing

power, but rather accepted a ceremonial promotion

from captain to colonel, a rank he remained at throughout his life thereafter. While at odds with western

military ranking for a colonel to rule a

country and serve as Commander-in-Chief of

its military, in Gaddafi's own words, Libya's

utopian society is “ruled by the people,”

so he needs no more grandiose title or supreme

military rank. Gaddafi's decision to remain

a colonel is not a new concept among military

coup leaders; Gamal

Abdel Nasser remained

a colonel after seizing power in Egypt, and

Jerry Rawlings, President of Ghana, held

no military rank higher than flight lieutenant.

In the same fashion, the Republic of El Salvador

was ruled by Lieutenant Colonel Oscar Osorio

(1950-1956), Lieutenant Colonel José María

Lemus (1956-1960), and Lieutenant Colonel

Julio Adalberto Rivera (1962-1967).

Islamic socialism and pan-Arabism

Gaddafi based his new regime

on a blend of Arab nationalism, aspects of

the welfare state and what Gaddafi termed “direct,

popular democracy.” He called this

system “Islamic socialism” and

while he permitted private control over small

companies, the government controlled the

larger ones. Welfare, “liberation,” and

education were emphasized. He also imposed

a system of Islamic morals, outlawing alcohol

and gambling. To reinforce the ideals of

this socialist-Islamic state, Gaddafi outlined

his political philosophy in his Green

Book,

published in three volumes between 1975 and

1979. In practice, however, Libya's political

system is thought to be somewhat less idealistic

and from time to time Gaddafi has responded

to domestic and external opposition with

violence. His revolutionary committees called

for the assassination of Libyan dissidents

living abroad in April 1980, with Libyan

hit squads sent abroad to murder them. On

April 26, Gaddafi set a deadline of June

11 for dissidents to return home or be “in

the hands of the revolutionary committees.”

Nine Libyans were murdered during that time,

five of them in Italy.

External relations

With respect to Libya's

neighbors, Gaddafi followed Nasser's ideas

of pan-Arabism and became a fervent advocate

of the unity of all Arab states into one

Arab nation. He also supported pan-Islamism,

the notion of a loose union of all Islamic

countries and peoples. After Nasser's death

on September 28, 1970, Gaddafi attempted

to take up the mantle of ideological leader

of Arab nationalism. He proclaimed the “Federation of Arab

Republics” (Libya, Egypt and Syria)

in 1972, hoping to create a pan-Arab state,

but the three countries disagreed on the

specific terms of the merger. In 1974, he

signed an agreement with Tunisia's Habib

Bourguiba on a merger between the two countries,

but this also failed to work in practice

and ultimately differences between the two

countries would deteriorate into strong animosity.

Libya was also involved in a sometimes violent

territorial dispute with neighbouring Chad

over the Aouzou Strip, that Libya occupied

in 1973. This dispute eventually led to the

Libyan invasion of the country and to a conflict

that was ended by a ceasefire reached in

1987. The dispute was at the end settled

peacefully in June 1994 when Libyan troops

were withdrawn from Chad in full respect

for a judgement of the International Court

of Justice that was issued on 13 February

1994.[4]

Gaddafi also became a strong supporter of

the Palestine

Liberation Organization, which

ultimately harmed Libya's relations with

Egypt when in 1979 Egypt pursued a peace

agreement with Israel. As Libya's relations

with Egypt worsened, Gaddafi sought closer

relations with the Soviet Union. Libya became

the first country outside the Soviet bloc

to receive the supersonic MiG-25 combat fighters,

but Soviet-Libyan relations remained relatively

distant. Gaddafi also sought to increase

Libyan influence, especially in states with

an Islamic population, by calling for the

creation of a Saharan Islamic state and supporting

anti-government forces in sub-Saharan Africa.

Notable in his politics has been the support

for liberation movements, and also sponsoring

rebel movements in West Africa, notably Sierra

Leone and Liberia as well as Muslim groups.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, this support

was sometimes so freely given that even the

most unsympathetic groups could get Libyan

support. Often the groups represented ideologies

far away from Gaddafi's own. International

opinion was confused by these policies. Throughout

the 1970s, his regime was implicated in subversion

and terrorist activities in both Arab and

non-Arab countries. By the mid-1980s, he

was widely regarded in the West as the principal

financier of international terrorism. Reportedly,

Gaddafi was a major financier of the “Black

September Movement” which perpetrated

the Munich

massacre at the 1972 Summer Olympics,

and was accused by the United States of being

responsible for direct control of the 1986

Berlin discotheque bombing that killed three

people and wounded more than 200, of whom

a substantial number were U.S. servicemen.

He is also said to have paid “Carlos

the Jackal” to kidnap and then release

a number of the Saudi Arabian and Iranian

oil ministers.

Tensions between Libya and the West reached

a peak during the Ronald

Reagan administration,

which tried to overthrow Gaddafi. The Reagan

administration viewed Libya as a belligerent

rogue state because of its uncompromising

stance on Palestinian independence, its support

for revolutionary Iran in its 1980-1988 war

against Saddam Hussein's Iraq and its backing

for “liberation

movements” in the developing world.

Reagan himself dubbed Gaddafi the “mad

dog of the Middle East.” In March 1982

the U.S. declared a ban on the import of

Libyan oil and the export to Libya of US

oil industry technology; European nations

did not follow suit.

In 1984, British police

constable Yvonne Fletcher was shot outside

the Libyan Embassy in London while policing

an anti-Gaddafi demonstration. A burst of

machine-gun fire from within the building

was suspected of killing her, but Libyan

diplomats asserted their diplomatic immunity

and were repatriated. The incident led to

the breaking-off of diplomatic relations

between the United Kingdom and Libya for

over a decade.

The U.S. attacked Libyan patrol boats from

January to March 1986 during clashes over

access to the Gulf of Sidra, which Libya

claimed as territorial waters. Later, on

April 15, 1986, Ronald Reagan ordered major

bombing raids, dubbed Operation El Dorado

Canyon, against Tripoli and Benghazi killing

45 Libyan military and government personnel

as well as 15 civilians. This strike followed

U.S. interception of Telex messages from

Libya's East Berlin embassy suggesting Libyan

government involvement in a bomb explosion

in West Berlin's La Belle discotheque, a

nightclub frequented by U.S. servicemen on

April 5. Among the fatalities of the April

15 retaliatory attack by the U.S. was Gaddafi's

adopted daughter.

In late 1987 a merchant vessel, the MV Eksund,

was intercepted. Destined for the IRA, a

large consignment of arms and explosives

supplied by Libya was recovered from the

Eksund. British intelligence believed this

was not the first and that Libyan arms shipments

had previously reached the IRA. (See Provisional

IRA arms importation)

For most of the 1990s, Libya

endured economic sanctions and diplomatic

isolation as a result of Gaddafi's refusal

to allow the extradition to the United States

or Britain of two Libyans accused of planting

a bomb on Pan Am Flight 103, which exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland.

Through the intercession of South African

President Nelson Mandela - who made a high-profile

visit to Gaddafi in 1997 - and U.N. Secretary-General

Kofi Annan, Gaddafi agreed in 1999 to a compromise

that involved handing over the defendants

to the Netherlands for trial under Scottish

law. U.N. sanctions were thereupon suspended,

but U.S. sanctions against Libya remained

in force.

In August 2003, two years

after Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi's

conviction, Libya wrote to the United

Nations formally accepting

'responsibility for the actions of its officials'

in respect of the Lockerbie bombing and agreed

to pay compensation of up to $2.7 billion – or

up to $10 million each – to the families

of the 270 victims. The same month, Britain

and Bulgaria co-sponsored a U.N. resolution

which removed the suspended sanctions. (Bulgaria's

involvement in tabling this motion led to

suggestions that there was a link with the

HIV trial in Libya in which 5 Bulgarian nurses,

working at a Benghazi hospital, were accused

of infecting 426 Libyan children with HIV.)

Forty per cent of the compensation was then

paid to each family, and a further 40% followed

once U.S. sanctions were removed. Because

the U.S. refused to take Libya off its list

of state sponsors of terrorism, Libya retained

the last 20% ($540 million) of the $2.7 billion

compensation package.

On June 28, 2007 Megrahi

was granted the right to a second appeal

against the Lockerbie bombing conviction.

One month later, the Bulgarian medics were

released from jail in Libya. They returned

home to Bulgaria and were pardoned by Bulgarian

president, Georgi Parvanov.

Western Openness

Simultaneously, Gaddafi also emerged

as a popular African leader. As one of the

continent's longest-serving, post-colonial

heads of state, the Libyan leader enjoyed

a reputation among many Africans as an experienced

and wise statesman who had been at the forefront

of many struggles over the years. Gaddafi

earned the praise of Nelson Mandela and

others, and was a prominent figure

in various pan-African organizations, such

as the Organization of African Unity (now

replaced by the African Union). He was also

seen by many Africans as a humanitarian,

pouring large amounts of money into sub-Saharan

states. Large numbers of Africans have come

to Libya to take advantage of the availability

of jobs there. In addition, many economic

migrants, primarily from Somalia and Ghana,

use Libya as a staging-post to reach Italy

and other European countries.

Gaddafi also appeared to be attempting to

improve his image in the West. Two years

prior to the terrorist attacks of September

11, 2001, Libya pledged its commitment to

fighting Al-Qaeda and offered to open up

its weapons program to international inspection.

The Clinton

administration did not pursue

the offer at the time since Libya's weapons

program was not then regarded as a threat,

and the matter of handing over the Lockerbie

bombing suspects took priority. Following

the attacks of September 11, Gaddafi made

one of the first, and firmest, denunciations

of the Al-Qaeda bombers by any Muslim leader.

Gaddafi also appeared on ABC for an open

interview with George Stephanopoulos, a move

that would have seemed unthinkable less than

a decade earlier.

There are many explanations for the change

of Gaddafi's politics. The most obvious is

that the once very rich Libya became much

less wealthy as oil prices dropped significantly

during the 1990's. Since then, Gaddafi has

tended to need other countries more than

before and hasn't been able to dole out foreign

aid as he once did. In this environment,

the increasingly stringent sanctions placed

by the UN and US on Libya made it more and

more isolated politically and economically.

Another possibility is that strong Western

reactions have forced Gaddafi into changing

his politics. It is also possible that realpolitik

changed Gaddafi. His ideals and aims did

not materialize: there never was any Arab

unity, the various armed revolutionary organizations

he supported did not achieve their goals,

and the demise of the Soviet Union left Gaddafi's

main symbolic target, the United States,

stronger than ever.

Following the overthrow

of Saddam

Hussein by U.S. forces in

2003, Gaddafi announced that his nation

had an active weapons of mass destruction

program, but was willing to allow international

inspectors into his country to observe

and dismantle them. President George

W. Bush and other supporters of the

Iraq War portrayed Gaddafi's announcement

as a direct consequence of the Iraq War

by stating that Gaddafi acted out of fear

for the future of his own regime if he

continued to keep and conceal his weapons.

Italian Premier Silvio Berlusconi, a supporter

of the Iraq War, was quoted as saying that

Gaddafi had privately phoned him, admitting

as much. Many foreign policy experts, however,

contend that Gaddafi's announcement was

merely a continuation of his prior attempts

at normalizing relations with the West

and getting the sanctions removed. To support

this, they point to the fact that Libya

had already made similar offers starting

four years prior to it finally being accepted.

International inspectors turned up several

tons of chemical weaponry in Libya, as

well as an active nuclear weapons program.

As the process of destroying these weapons

continued, Libya improved its cooperation

with international monitoring regimes to

the extent that, by March 2006, France

was able to conclude an agreement with

Libya to develop a significant nuclear

power program.

In March 2004, British prime

minister Tony Blair became one of the first

western leaders in decades to visit Libya

and publicly meet Gaddafi. Blair praised

Gaddafi's recent acts, and stated that he

hoped Libya could now be a strong ally in

the international war on terrorism. In the

run-up to Blair's visit, the British ambassador

in Tripoli, Anthony Layden, explained Libya's

and Gaddafi's political change thus:

“35 years of total

state control of the economy has left them

in a situation where they're simply not

generating enough economic activity to

give employment to the young people who

are streaming through their successful

education system. I think this dilemma

goes to the heart of Colonel Gaddafi's

decision that he needed a radical change

of direction.”

On May 15, 2006, the U.S.

State Department announced that it would

restore full diplomatic relations with Libya,

once Gaddafi declared he was abandoning Libya's

weapons of mass destruction program. The

State Department also said that Libya would

be removed from the list of nations supporting

terrorism. On August 31, 2006, however,

Gaddafi openly called upon his supporters

to “kill

enemies” who asked for political change.

In July 2007, French president

Nicolas Sarkozy visited Libya and signed

a number of bilateral and multilateral (EU)

agreements with Gaddafi.

Internal dissent

In October 1993, there was an unsuccessful

assassination attempt on Gaddafi by elements

of the Libyan army. In July 1996, bloody

riots followed a football match as a protest

against Gaddafi.

Fathi Eljahmi is a prominent dissident who

has been imprisoned since 2002 for calling

for increased democratization in Libya.

A website that actively sought

his overthrow was set up in 2006 and listed

343 victims of murder and political assassination.

The Libyan League for Human Rights (LLHR) – based

in Geneva – petitioned Gaddafi to set

up an independent inquiry into the February

2006 unrest in Benghazi in which some 30

Libyans and foreigners were killed.

In February 2011, following revolutions in neighbouring Egypt and Tunisia, protests against Gaddafi's rule began anew and in earnest. These escalated into an uprising that spread across the country, with the forces opposing Gaddafi establishing a government based in Benghazi. This led to the 2011 Libyan Civil War, which included a military intervention by a NATO-led coalition to enforce a Security Council resolution calling for a no-fly zone and protection of civilians in Libya.

Gaddafi and his forces lost the Battle of Tripoli in August, and on September 16, 2011 the newly formed government took Libya's seat at the UN, replacing Gaddafi. He retained control over parts of Libya, most notably the city of Sirte, to which it was presumed that he had fled. Although Gaddafi's forces initially held out against the NTC's advances, Gaddafi was captured alive as Sirte fell to the rebel forces on October 20, 2011 and he died the same day under unclear circumstances.

Personal life

Gaddafi has eight children,

seven of them sons. His eldest son, Muhammad

Gaddafi, is by a wife now in disfavor, but

runs the Libyan Olympic Committee and owns

all the telecommunication companies in Libya.

The next eldest Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, was

born in 1972, is a painter, runs a charity

which has been involved in negotiating freedom

for hostages taken by Islamic militants,

especially in the Philippines. In 2006, after

sharply criticizing his father's regime,

Saif Al Islam briefly left Libya, reportedly

to take on a position in banking outside

of the country. He returned to Libya soon

after, launching an environment friendly

initiative to teach children how they can

help clean up parts of Libya. He has also

been on the forefront of resolving the HIV

case of a Palestinian doctor and Bulgarian

nurses described previously.

The third eldest, Al-Saadi

Gaddafi, is married to the daughter of a

military commander. Al Saadi runs the Libyan

Football Federation, plays for Italian Serie

A team U.C. Sampdoria, made billions of dollars

in the petrol industry and produces films.

The fourth eldest, Mutasim-Billah

Gaddafi, was a Lieutenant Colonel in the

Libyan army. He fled to Egypt after allegedly

masterminding an Egyptian backed coup attempt

against his father. Gaddafi forgave

Mutasim-Billah and he returned to Libya where

he now holds the post of national security

adviser and heads his own unit within the

army. Saif Al Islam and Mutasim-Billah are

both seen as possible successors to their

father.

The fifth eldest, Hannibal

once worked for a public marine transportation

company in Libya. He is most notable for

being involved in a series of violent incidents

throughout Europe, including charges against

him for beating up his then pregnant girlfriend,

Alin Skaf. (In September

2004, Hannibal was involved in a police chase

in Paris.)

Gaddafi has two younger sons, Saif Al Arab

and Khamis, a police officer in Libya.

Gaddafi's only daughter is Ayesha Gaddafi,

a lawyer who had joined the defense team

of executed former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.

She married a cousin of her father in 2006.

Gaddafi's reportedly adopted

daughter, Hanna, was killed in the 1986 USAF

bombing raid. At a “concert for peace” held

on April 15, 2006 in Tripoli to mark the

20th anniversary of the bombing raid, U.S.

singer Lionel Richie told the audience:

“Hanna will be honored

tonight because of the fact that you've

attached peace to her name.”

In January 2002, Gaddafi purchased a 7.5%

share of Italian football club Juventus for

USD 21 million, through Lafico (“Libyan

Arab Foreign Investment Company”).

Though Gaddafi is an avid football fan, this

more importantly continued a longstanding

association with the late Gianni Agnelli,

the primary investor in Fiat. Gaddafi has

also become involved in chess: in March 2004,

FIDE, the game's world governing body, announced

that he would be providing prize money for

the World Championship, held in June-July

2004 in Tripoli.

Lahore, Pakistan's primary cricket stadium,

Gaddafi Stadium, is named after him.

In addition to his Green

Book, al-Gaddafi

is the author of a 1996 collection of short

stories, Escape to Hell.

In November 2002, he hosted the Miss Net

World beauty pageant, a first for Libya and

as far as is known, the world's first to

be held on the internet.

Gaddafi's personal bodyguard,

the Amazonian guard, is composed of women

who are martial arts experts and highly-trained

in the use of weapons. The Amazonian guard

accompanied him on his 2004 visit to Brussels.

The Amazonian Guard sparked

an international incident in 2006 when Gaddafi

landed in Nigeria with over two hundred armed

guards for a summit. Nigerian security officials

refused to allow the Libyans entry based

on their armaments, and Gaddafi angrily resolved

to set off on foot 40 km to Nigeria's capital

from the airport. The Nigerian President

personally intervened, and a compromise was

sought. However, the Libyans rejected mediation

and threatened to fly home, whereupon the

Nigerians revoked their compromise offers

and announced that the Libyans could only

bring in 8 pistols, which is the limit for

international delegations. The Libyans finally

backed down and complied with the Nigerians

after several hours.

Gaddafi holds an honorary

degree from Megatrend University in Belgrade

proclaimed by former Yugoslav President Zoran

Lilic.

Quotations

“Ronald Reagan plays

with fire! He sees the world like the theater.”

“I have nothing

but scorn for the notion of an Islamic

bomb. There is no such thing as an Islamic

bomb or a Christian bomb. Any such weapon

is a means of terrorizing humanity, and

we are against the manufacture and acquisition

of nuclear weapons. This is in line with

our definition of—and

opposition to—terrorism.”

“Israel is a colonialist-imperialist

phenomenon. There is no such thing as an

Israeli people. Before 1948, world geography

knew of no state such as Israel. Israel

is the result of an invasion, of aggression.”

“I've got two idols

in my life — President

Lincoln and Dr. Sun Yat-sen.”

“Irrespective of

the conflict with America, it is a human

duty to show sympathy with the American

people and be with them at these horrifying

and awful events which are bound to awaken

human conscience.” — September

11, 2001

“Man’s freedom

is lacking if somebody else controls what

he needs, for need may result in man’s

enslavement of man.”

“We have four million

Muslims in Albania. There are signs that

Allah will grant Islam victory in Europe – without

swords, without guns, without conquests.

The fifty million Muslims of Europe will

turn it into a Muslim continent within

a few decades. Europe is in a predicament,

and so is America. They should agree to

become Islamic in the course of time, or

else declare war on the Muslims.”

“The Libyans said

they'll buy their way out of these three

[terrorism] black lists. We'll pay so much,

to hell with $2 billion or more. It's not

compensation. It's a price. The Americans

said it was Libya who did it. It is known

that the president was madman Reagan who's

got Alzheimer's and has lost his mind.

He now crawls on all fours.”

Name

Due to the inherent difficulties

of transliterating written and regionally-pronounced

Arabic, Gaddafi's name can be transliterated

in many different ways. An article published

in the London Evening Standard in 2004 lists

a total of 37 spellings; a 1986 column by The

Straight Dope quotes a list of 32 spellings

known at the Library of Congress. Muammar

al-Gaddafi, used in this article, is the

spelling used by Time magazine and

the BBC. The Associated Press, CNN, and Fox

News use the spelling Moammar Gadhafi, Al-Jazeera

uses Muammar al-Qadhafi, the Edinburgh Middle

East Report uses Mu'ammar Qaddafi and the

U.S. Department of State uses Mu'ammar Al-Qadhafi.

In 1986, Gaddafi reportedly responded to

a Minnesota school's letter in English using

the spelling Moammar El-Gadhafi. Though

according to Gaddafi's personal website he

prefers the spelling Muammar Gadafi, the

domain name gives yet another version: al-Gathafi.

Sources: The

photograph was produced by Agência

Brasil, a public Brazilian news agency. Their website states: "O

conteúdo deste site é publicado

sob a licença Creative

Commons Atribuição 2.5 Brasil" (The

content of this website is published under

the Creative

Commons License Attribution 2.5 Brazil |