Background & Overview

by Mitchell Bard

(Updated February 2016)

From September 2000 to mid-2005, hundreds of Palestinian suicide bombings and terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians killed more nearly 1,000 innocent people

and wounded thousands of others. In response, Israel's

government decided to construct a security

fence that would run near the “Green

Line” between Israel and

the West Bank to prevent Palestinian

terrorists from easily infiltrating into Israel proper. The

project had the overwhelming support of the Israeli public and was deemed legal by Israel's Supreme Court.

Israel's fence garnered international condemnation, but the outrage is a clear double standard - there is nothing new about the construction

of a security fence. Many nations have fences to protect their

borders - the United States, for example, has one to prevent illegal immigration. In fact, when the West Bank fence was approved, Israel had already built a fence surrounding the Gaza

Strip that had worked - not a single suicide

bomber has managed to cross Israel's border with Gaza.

- Israel is Forced to Act

- Making Terrorism More Difficult

- Other Benefits

- Planning the Fence Route

- High Tech Fence

- Politics

- Precedents

- Inconvenience vs Saving Lives

- 2016 Security Fence

Israel is Forced to Act

The

Palestinians committed themselves in the Oslo

accords and in the road map to dismantle terrorist networks and confiscate illegal weapons. After

more than 10 years of negotiations, and a mounting toll of Israeli civilian

casualties, however, it became clear to the Israeli people that the Palestinian Authority (PA) made

a strategic choice to use terror to achieve its aims and that something

had to be done to protect the civilian population.

“It obliges us to establish a barrier wall which

is the only thing that can minimize the infiltration of these male and

female suicide bombers,” said Defense Minister Benjamin Ben-Eliezer,

who has emphasized that “the fence is not political, [and] is not

a border.”

Some Israelis oppose the fence either because they

fear it will constitute a recognition of the 1949 armistice line as

a final border. Jews living in the West Bank, beyond the planned route

of the fence, in particular, argue that they are now being left relatively

unprotected and worry that they might be forced to relocate behind the

fence if it does become a political border in the future.

Making Terrorism

More Difficult

Before the construction of the fence, and in many places

where it has not yet been completed, a terrorist need only walk across

an invisible line to cross from the West Bank into Israel. No barriers

of any kind exist, so it is easy to see how a barrier, no matter how

imperfect, won't at least make the terrorists' job more difficult. Approximately

75 percent ofthe suicide bombers who attacked targets inside Israel

came from across the border where the first phase of the fence was built.

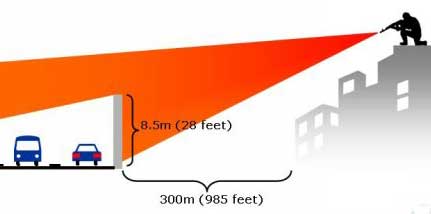

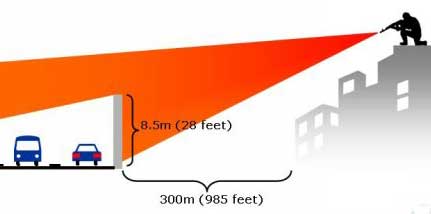

This diagram shows why a wall is being built in

a few specific places where Palestinian snipers have terrorized motorists.

This diagram shows why a wall is being built in

a few specific places where Palestinian snipers have terrorized motorists. |

During the 34 months from the beginning of the violence

in September 2000 until the construction of the first continuous segment

of the security fence at the end of July 2003, Samaria-based terrorists

carried out 73 attacks in which 293 Israelis were killed and 1950 wounded.

In the 11 months between the erection of the first segment at the beginning

of August 2003 and the end of June 2004, only three attacks were successful,

and all three occurred in the first half of 2003.

Since construction of the fence began, the number of attacks has declined

by more than 90%. The number of Israelis murdered and wounded has decreased

by more than 70% and 85%, respectively, after erection of the fence.

Even the Palestinian terrorists

have addmitted the fence is a deterrent.

On November 11, 2006, Islamic

Jihad leader Abdallah Ramadan

Shalah said on Al-Manar

TV the terrorist

organizations had every intention of continuing suicide

bombing attacks, but that their

timing and the possibility of implementing

them from the West

Bank depended

on other factors. “For example,” he

said, “there is the separation fence,

which is an obstacle to the resistance, and

if it were not there the situation would

be entirely different.”

The value of the fence in saving lives is evident from the data: In 2002, the year before construction started, 457 Israelis were murdered; in 2009, 8 Israelis were killed.

In order to thwart possible Hezbollah infiltrations through the border with Lebanon, in April 2015 it was announced that the IDF had begun construction of a 7-mile long land berm (earth barrier) on the Northern border. The IDF is “executing a significant engineering endeavor, creating obstacles in the terrain so as to use if for our defense” by constructing the border, according to IDF Colonel Alon Mendes. The barrier is expected to be expanded in the future.

Other Benefits

The Green Line is crossed by numerous dirt roads and it is impossible to patrol it.

Many Palestinians take advantage of these roads to come to work illegally

in Israel or to get between parts of the Palestinian administered territories

to avoid checkpoints. Some also cross to carry out terror operations

and theft. Since 1994, Palestinians, sometimes in cooperation with Israeli

middlemen, have stolen thousands of automobiles as well as farm machinery

and animals.1

Israelis living along the Green

Line, both Jews and Arabs, favor the fence to prevent infiltration

by suicide bombers and by thieves and vandals. In fact, the fence has

caused a revolution in the daily life of some Israeli Arab towns because

it has brought quiet, which has allowed a significant upsurge in economic

activity.

The Palestinians in the territories will also benefit

from the fence because it will reduce the need for Israeli military

operations in the territories, and the deployment of troops in Palestinian

towns. Onerous security measures, such as curfews and checkpoints, will

either be unnecessary or dramatically scaled back.

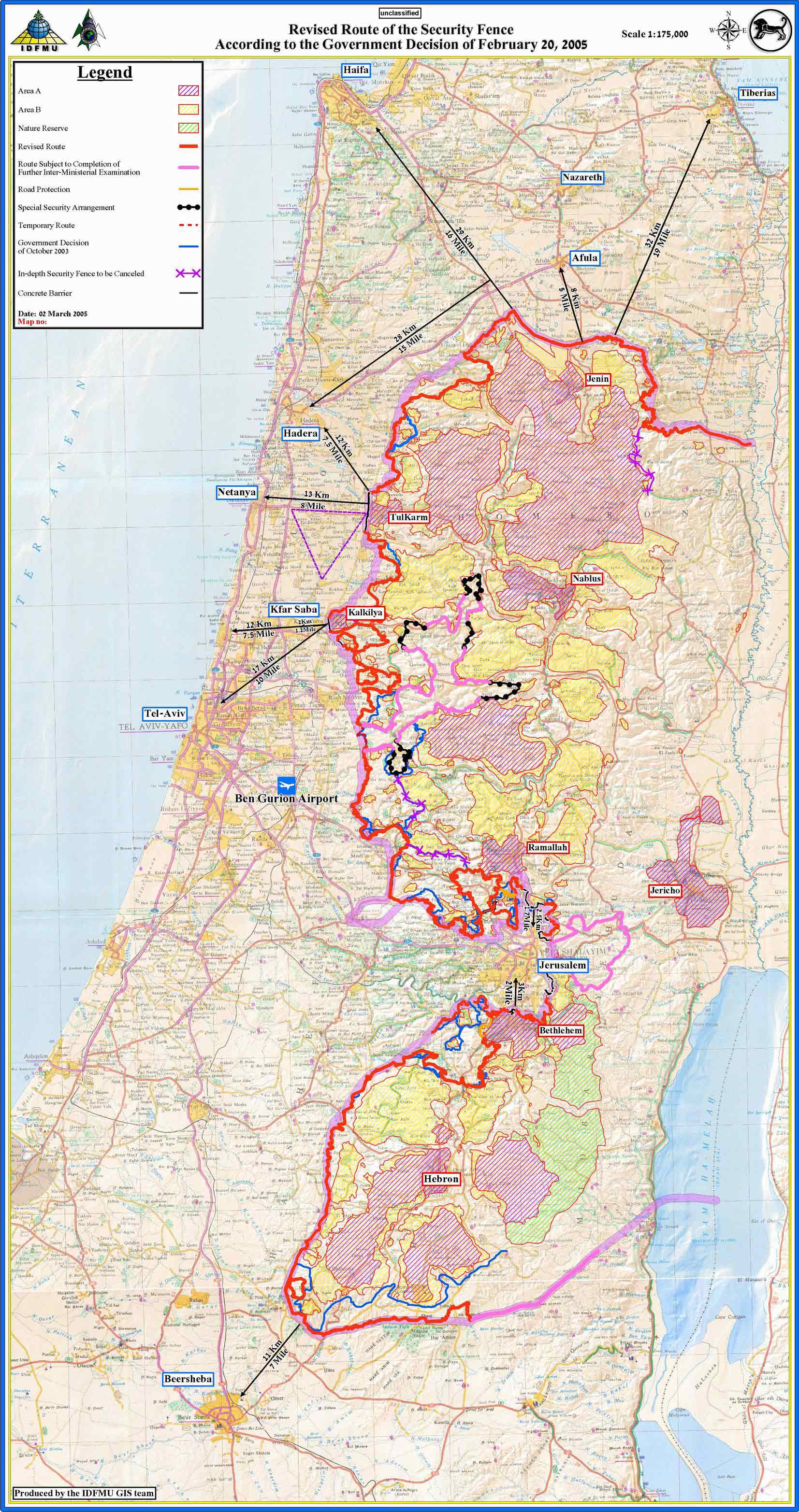

Planning the Route

The route of the fence must take into account topography,

population density, and threat assessment of each area. The fence is

scheduled to be built in stages. Phase A of construction, approximately

85 miles from Salem to Elkana was completed at the end of July 2003.

Phase B, which is about 50 miles, runs from Salem toward Bet- Shean,

through the Jezreel Valley and the Gilboa mountains. It was completed

in 2004.

Phase C of construction

incorporates Jerusalem.

During the “al-Aqsa intifada,” more

than 30 suicide bombings have targeted Jerusalem.

A total of 90 terrorist attacks have killed

170 people and injured 1,500 in the capital.

The original “Jerusalem Defense Plan” approved

in March 2003 called for the fence to be

constructed around three parts of the capital,

which has been the most frequent target

of suicide

bombers. This section of the fence

was expected to run about 40 miles around

the municipal boundaries of the city. Israeli

and Palestinian residents in areas along

the fence route filed legal challenges

that required changes in the construction

plan. In March 2005, Israel announced

it would build a temporary fence separating Jerusalem from the West

Bank by July,

leaving the structure in place while legal

challenges to the permanent barrier are

decided by the courts.

The updated route

is to run about 32 miles around Jerusalem,

but was only 25 percent complete in July

2005. The fence along the southern rim,

encircling neighborhoods such as Har

Homa and Gilo is mostly complete. The

northern section that will incorporate Pisgat

Zeev and Neveh Ya'acov began more recently.

The government originally set September 1,

2005, as the deadline for completing the

Jerusalem barrier, but shortly after this

decision, the Interior Minister said it could

not be finished before December or January.

As of August 2008, nearly one-third of the

fence — about 30 miles of

the approximately 100 mile fence — remained

unfinished. The principal impediment to finishing

the job has been a shortage of funds, however,

about 2 miles of the fence has also been

held up

by ongoing legal appeals.

Phase D will span approximately

93 miles from Elkana to Ofer. In addition,

several special sections of the fence will

protect specific areas and populations.

An inside fence of 15 miles will protect

the road from the airport to Jerusalem.

A fence around the town of Ariel will stretch

about 35 miles and a 31 mile section will

traverse the road between Ariel and Kedumim.

A 32-mile span will go from Jerusalem to Gush

Etzion,

another 19 miles will surround Gush Etzion

(incorporating 10 settlements and approximately

50,000 Israelis), and the fence

will continue an additional 58 miles to Carmel.

The planned route was approximately 458 miles; however,

the plan has been repeatedly modified and, in February 2004, the government

announced its intention to shorten the route and move the barrier closer

to the 1949 armistice line to make it less burdensome to the Palestinians

and address U.S. concerns. The announced changes included the dismantling

of a small stretch of fence east of Kalkilya to make movement easier

for residents going into the West Bank. The government cancelled plans

to build deep trenches to protect Ben-Gurion Airport and Route 443 from

Modi'in to Jerusalem because of concern about the impact on the Palestinians

in the area.

In February 2005, the route

was again modified to take into account

the decision by the Israeli Supreme

Court to take greater account of the impact of

the fence on the Palestinians. The proposed

route runs closer to the Green

Line than the original plan approved

in October 2003. For the first time, however,

the fence will include Ma'aleh Adumim and

the surrounding settlements.

To the east of the town, a “ring road” will connect the northern and southern parts

of the West

Bank,

allowing Palestinians to travel between Jenin

and Hebron.

The route of the fence in the Gush

Etzion region was altered to exclude

four Palestinian villages whose residents

will have free access to Bethlehem.

A special protective wall will be built along

Route 60 that links Gush

Etzion with Jerusalem.

The route of the fence in the Hebron Hills,

which originally included several settlements and

a large expanse of land beyond the Green

Line, has been brought close to the Green

Line. This new route will include 7

percent of the West

Bank on its “Israeli” side — as

opposed to 16 percent in the original

plan — and

approximately 10,000 Palestinian residents.

One of the most controversial questions has been whether

to build the fence around Ariel, a town of approximately 20,000 people,

the second largest Jewish settlement in the territories. To incorporate Ariel, the fence would have to extend

approximately 12 miles into the West

Bank. The United States has opposed the inclusion of Ariel inside

the fence. In the short-run, Israel decided to build a fence around

Ariel, but said in February 2005 it would be incoporated within the

main fence at a later stage.

As a result of the modifications,

the length of the barrier is expected to

be approximately 500 miles. As of July 2010,

only about 320 miles (64%) of the barrier

was completed

and much of the rest was tied

up by petitions to the Israeli Supreme

Court and Justice Ministry deliberations.

Work

is now being done on mostly constructed sections

of the fence and areas that have to be rerouted

in response to court

rulings. The Defense Ministry previously projected

the fence would be completed by 2010,

but now it does not give an end date.

The secruity fence is

the largest infrastructure project in Israel's

history. The cost of the project has ballooned

from an

expected $1 billion to more than $2.1 billion.

Each kilometer of fence costs approximately

$2 million.

Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon has said that

the “fence is not a political border, it is not a security border,

but rather another means to assist in the war on terror.” As such,

Israel has repeatedly stated its willingness to move or remove the fence

as part of a Palestinian-Israeli peace agreement.

In the past, Israel has been willing to move fences,

even elaborate and expensive ones such as this security barrier. Along

the border with Lebanon, where

a high-tech fence equipped with surveillance cameras and sensors closely

monitors the situation, Israel has moved sections of fence more than

a dozen times in order to implement its U.N.-certified

withdrawal from Lebanon.

Israel has maintained that the security fence will

be an obstacle to terrorism, but not to an agreement with the Palestinians.

“I do not believe that the routing of the fence can prevent a

real accord,” said Finance Minister Benjamin

Netanyahu. “A fence can always be moved.”

A High-Tech Fence

Although

critics have sought to portray the security

fence as a kind of "Berlin

Wall," it is nothing of the sort. First,

unlike the Berlin Wall, the fence does not

separate one people, Germans from Germans,

and deny freedom to those on one side. Israel's

security fence separates two peoples, Israelis

and Palestinians, and offers freedom and

security for both. Second, while Israelis

are fully prepared to live with Palestinians,

and 20 percent of the Israeli population is already Arab, it is the Palestinians who

say they do not want to live with any Jews

and call for the West Bank to be judenrein.

Third, the fence is not being constructed

to prevent the citizens of one state from

escaping; it is designed solely to keep terrorists

out of Israel. Finally, only a tiny fraction

of the total length of the barrier (less

than 3% or about 10 miles) is actually a

30 foot high concrete wall, and that is being

built in three areas where it will prevent

Palestinian snipers from around the terrorist

hotbeds of Kalkilya and Tul Karm from shooting

at cars as they have done for the last three

years along the Trans-Israel Highway, one

of the country's main roads. The wall also

takes up less space than the other barriers,

only about seven feet, so it did not have

a great impact on the area where it was built.

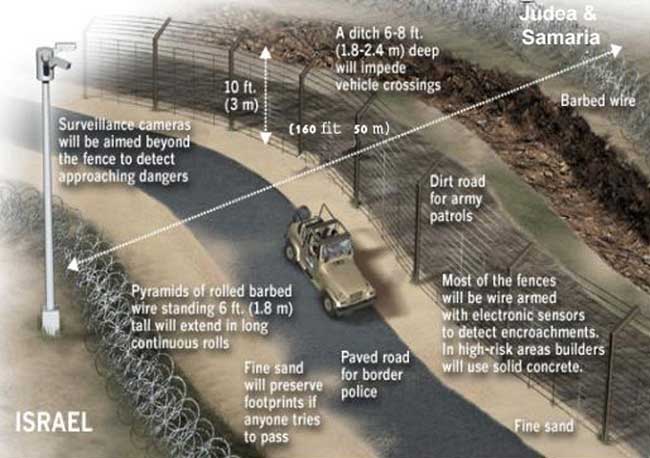

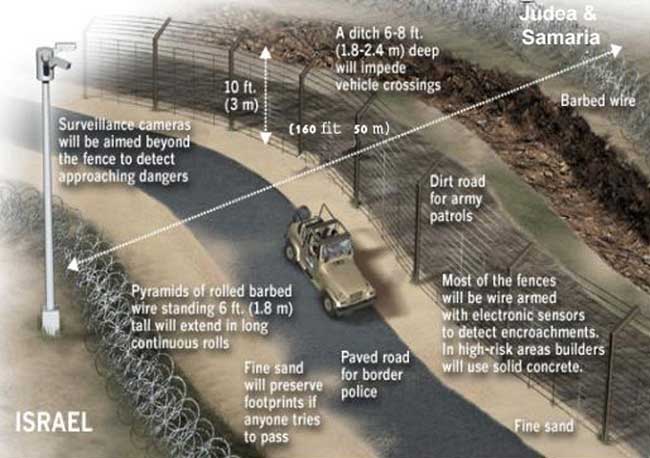

Most of the barrier will be a chain-link type fence

similar to those used all over the United States combined with underground

and long-range sensors, unmanned aerial vehicles, trenches, landmines

and guard paths. Manned checkpoints will constitute the only way to

travel back and forth through the fence. The barrier is altogether about

160 feet wide in most places.

The land used in building the security fence is seized

for military purposes, not confiscated, and it remains the property

of the owner. Legal procedures are already in place to allow every owner

to file an objection to the seizure of their land. Moreover, property

owners are offered compensation for the use of their land and for any

damage to their trees.

Politics

The construction of the fence has been slowed by political

divisions over the precise route. The most controversial aspects of

the project are decisions regarding the inclusion of Jewish settlements.

Israel wants to include as many Jews within the fence, and as few Palestinians

as possible. To incorporate some of the larger settlements, however,

it would be necessary to build the fence with bulges inside the West

Bank. The Bush Administration understands Israel's security arguments

regarding the need for the fence, but does not want it to prejudge negotiations

or to threaten the possibility of creating a contiguous Palestinian

state and therefore has pressured Israel to restrict construction to

the area along the pre-1967 border, or as close as possible to it. The

so-called “Green Line,”

however, was not an internationally recognized border, it ws an armistice

line between Israel and Jordan pending the negotiation of a final border.

Building the fence along that line would have been a political statement

and would not accomplish the principal goal of the barrier, namely,

the prevention of terror.

|

Most

of the fence runs roughly along the Green

Line. The fence is about a mile to the east in three places that

allows the incorporation of the settlements of Henanit, Shaked, Rehan,

Salit, and Zofim. The most significant deviation from the 1967 line

is a bulge of less than four miles around the towns of Alfei Menashe

and Elkanah where about 8,000 Jews live. In some places, the fence is

actually inside the “Green

Line.”

The fence especially complicates

potential negotiations related to Jerusalem as

it will make it more difficult to devise

a compromise that would lead to a division

of the city, an idea that is unpopular with

Israelis. Since the fence is not permanent,

it is possible that it could be relocated,

or become unnecessary if a peace agreement

were reached, in which case a political settlement

could be reached.

In the meantime, an estimated

55,000 Jerusalem Arabs from four neighborhoods

are expected to be on the Palestinian side

of the fence while 180,000 Arab residents

of the city remain on the Israeli side

of the barrier. Over the past year, thousands

of Arab have moved to more central East

Jerusalem neighborhoods to stay on the Israeli

side of the fence. Representatives of some

Arab neighborhoods have gone so far as to

petition the Israeli Supreme

Court to order the Defense Ministry

to reroute the fence so it runs to the

east of the neighborhoods of Anata, Ras

Hamis and Shuafat and allows them to be

on the Israeli side. To alleviate the inconvenience

caused by the fence, the Cabinet approved a plan

to construct 11 passages through the barrier

to facilitate movement in and out of

the city. In addition, the government is

allocating NIS 8 million for the municipality

to provide special services to Arab residents

of Jerusalem who will be adversely affected

by the fence.

Palestinians complain that the fence creates “facts

on the ground,” but most of the area incorporated within the fence

is expected to be part of Israel in any peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Israeli negotiators have always envisioned the future border to be the

1967 frontier with modifications to minimize the security risk to Israel

and maximize the number of Jews living within the State. When the Palestinians

stop the violence and negotiate in good faith, it may be possible to

remove the fence, move it, or open it in a way that offers freedom of

movement. Israel, for example, moved a similar fence when it withdrew

from southern Lebanon. The

fence may stimulate the Palestinians to take action against the terrorists

because the barrier has shown them there is a price to pay for sponsoring

terrorism.

Precedents

It is not unreasonable or

unusual to build a fence for security purposes.

Israel already has fences along the frontiers

with Lebanon, Syria,

and Jordan,

so building a barrier to separate Israel

from the Palestinian Authority is

not revolutionary. Most nations have fences

to protect their borders and several use

barriers in political disputes:

- The United States

is building a fence to keep out illegal

Mexican immigrants.

- Spain built a fence,

with European Union funding, to separate

its enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla from

Morocco to prevent poor people from sub-Saharan

Africa from entering Europe.

- India constructed

a 460-mile barrier in Kashmir to halt

infiltrations supported by Pakistan.

- Saudi

Arabia built a 60-mile barrier

along an undefined border zone with Yemen to

halt arms smuggling of

weaponry and announced plans

in 2006 to build a 500-mile fence along

its border with Iraq.

- Turkey built a barrier

in the southern province of Alexandretta,

which was formerly in Syria and is an

area that Syria claims as its own.

- In Cyprus, the UN

sponsored a security fence reinforcing

the island’s de facto partition.

- British-built barriers

separate Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods

in Belfast

Ironically, after condemning

Israel’s barrier, the UN announced plans

to build its own fence to improve security

around its New York headquarters.

Inconvenience

Versus Saving Lives

Every effort is being made

to exclude Palestinian villages from the

area within the fence and no territories

are being annexed. The land used in building

the security fence is seized for military

purposes, not confiscated, and it remains

the property of the owner. Legal procedures

are already in place to allow every owner

to file an objection to the seizure of their

land. In addition, Israel has budgeted $540

million to ease

the lives of Palestinians affected

by the fence by building extra roads, passageways,

and tunnels.

Israel is doing its best

to minimize the negative impact on Palestinians

in the area of construction and has created

70 agricultural passageways to allow farmers

to continue to cultivate their lands, and

crossing points to allow the movement of

people and the transfer of goods. Moreover,

property owners are offered compensation

for the use of their land and for any damage

to their trees. Contractors are responsible

for carefully uprooting and replanting the

trees. So far, more than 60,000 olive trees

have been relocated in accordance with this

procedure. In addition, the government

has spent NIS 2 billion to construct

an alternative system of roads, underpasses

and tunnels to facilitate Palestinian travel

around the barrier.

Additionally, the

Civil Administration in Judea and Samaria opened a District Coordinating

Office (DCO) in December 2004, to assist Palestinians living in

the Jerusalem area affected

by the construction of the fence.

Operations of this office will focus on assisting the 110,000 Palestinians

living in Abu Dis and Eizariya, in the areas east of Jerusalem and Kalandiya,

A Ram and Bir Naballah to the north. The office will deal with issues concerning education, religion,

employment, humanitarian assistance and will coordinate entry of Palestinians

into Jerusalem.

Despite Israel's best efforts, the fence

has caused some injury to residents near

the fence. Israel’s Supreme

Court took up the grievances of Palestinians and ruled that

the construction of the security fence is

consistent with international law and was

based on Israel’s security requirements

rather than political considerations. It

also required the government to move the

fence in the area near Jerusalem to make things easier for the Palestinians.

Though the Court’s

decision made the government’s

job of securing the population from terrorist

threats more difficult, costly, and time-consuming,

the Prime Minister immediately accepted

the decision and began to reroute the fence

and to factor the Court’s

ruling into the planning of the rest of the

barrier.

Palestinians continue to

challenge the route of the fence and the

Court has issued a number of decisions, some

favoring the existing route and others, the

petitioners. For example, in June

2006, the Court ordered Israel to

tear down a two-mile stretch of fence around

Zufin, a settlement near the West

Bank town of Kalkilya

and reroute it to accommodate Palestinians

in the area. In July 2008, the government

responded to another court decision and agreed

to move part of the barrier that was on the

land of the residents of the village of Bil’in.

The security fence does create some inconvenience to

Palestinians, but it also saves lives. The deaths of Israelis caused

by terror are permanent and irreversible whereas the hardships faced

by the Palestinians are temporary and reversible.

2016 Security Fence

Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu unveiled a proposal to surround Israel with a security fence in February 2016, stating that Israel needed to protect itself from Palestinian and terrorist infiltration. The Prime Minister received criticism from world leaders as he referred to citizens of Israel's neighboring countries as well as Palestinians as "wild beasts." Netanyahu described the border project as a multi-year plan to surround all of Israel with security fences. The Prime Minister made the announcement while visiting a newly constructed fence between Israel and Jordan in February 2016, and also said that the Israeli government would be looking to permanently fix gaps in the current seperation wall. Education Minister Naftali Bennett expressed disdain for Netanyahu's proposal, explaining “the prime minister spoke today about how fences are needed. We are wrapping ourselves in fences. In Australia and New Jersey there is no need for fences.”

Following months of daily lone-wolf terror attacks dubbed by Palestinian leadership as the “Days of rage,” Israeli officials announced that Israel would fill in gaps in the separation barrier in Jerusalem, and complete the barrier in Tarkumiya. Some Palestinians who participated in the late-2015, early-2016 wave of violence used gaps in the security fences to enter Israel illegally without proper permits.

Sources:Near

East Report, (July 15, 2002; July

28, 2003);

Jerusalem Report, (September 8,

2003, December 7, 2005,

July 10, 2007; July 28, 2008);

Ha'aretz,

(February 25, 2004);

Israeli

Foreign Ministry;

Ministry

of Defense;

B'tselem, (January 15,

2006);

Miller, Elhanan. “Land berm going up on Lebanon border to thwart Hezbollah,” Times of Israel(April 15, 2015);

Beaumont, Peter.

“Netanyahu plans fence around Israel to protect it from 'wild beasts',” The Gaurdian (February 10, 2016);

Ravid, Barak. “After Terror Attacks, Israel to Complete Separation Barrier Construction Around Jerusalem, Southern West Bank,” Haaretz, (March 9, 2016);

Color maps courtesy of MidEast

Web

1MidEast

Web

2JTA,

(June 18, 2003).

|