Virtual Jewish World: Lvov, Ukraine

Virtual Jewish World: |

|

|---|

Lvov was a walled city, as was common of cities during the Middle Ages. In the 14th century, Lvov had two Jewish communities, one inside the walled city and one that lay on the outskirts. The two neighborhoods had separate synagogues and mikvahs (ritual baths), but the cemetery they shared. By 1550, Lvov had a Jewish population of nearly 1,000.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, the community suffered from foreign invasion, mostly by the Tartars, and also from a series of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, fired and epidemics. Despite these setbacks, the Jewish community grew significantly after Lvov was annexed to the Polish Kingdom in 1349.

During this time, Jews engaged in such trades as moneylending, tax farming, and wholesale and retail trade. They were also very active in the trade of perfumes, silk goods, and other exotic items that they imported throughout Poland. They expanded commercial ties with Nuremberg, Danzig and Breslau. They also began to import goods from Hungary, Holland and England, and dealt in grain, cattle, hides, wine and other goods of this nature. Also, by 1610, there were 70 Jewish butchers living in Lvov, as well as several tailors, tanners and silversmiths. The poorer Jews, mostly living outside the city walls, were peddlers.

From the second half of the 16th century, Yitzhak ben Nahman and his descendants led the community for 100 years. A gothic-style synagogue was built in 1571, which remained standing until World War II, known as the Golden Rose Synagogue. In 1682, another congregation was built for the community living outside the city walls.

In the early 17th century, a violent conflict erupted in Lvov between the Jews and the Jesuits over the Golden Rose Synagogue, which had been constructed inside the old city walls by the Nachmanovich family. The Jesuits claimed the land that the synagogue sat on was theirs, but the Jews were able to prove otherwise.

By 1708, the center of the city was filled with Jewish stores, and the population increased steadily, despite a significant number of deaths that occurred due to the frequent invasions on the previous century.

In 1772, Galicia became part of the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Lvov again changed names, this time to Lemberg. Jews’ rights were curtailed, and by the turn of the century, only those Jews who were wealthy and educated, and who adopted the German way of life, were able to live outside the city’s Jewish quarter. By 1800, the first two original Jewish communities no longer existed as such, and the main Jewish quarter lay outside the walls of the old city. Most Jews at this time were shopkeepers or craftsmen.

Despite a marriage tax and residence restrictions placed upon them by Lvov’s new rulers, the Jewish population again grew, reaching over 19,000 in 1826, caused by a influx of Jews into the city from provincial towns. However, due to the overcrowding, unhealthy living conditions and a typhoid epidemic, many perished.

Economic conditions worsened when Jews were cut off from the markets in Danzig and Leipzig. They were excluded from the grain trade as well as from traditional leaseholdings. They made a resurgence however when they entered the trade business between Russia and Austria. Jews became army suppliers and played a part in the city’s industrial development.

In 1820, the Jews owned 265 of Lvov’s 290 stores. The city boasted a Jewish hospital as well as an orphanage. It was around this time that Jews began to be accepted into Lvov University, and the rise of the professional class was underway. These professionals together with the sons of wealthy merchants became the first adherents to the Haskalah (the Jewish enlightenment). A Jewish elementary school was founded in 1844-1845, as well as a Temple that held bat mitzvah classes for girls.

Hasidism, a sect of Orthodox Judaism, also began to spread around this time, and Lvov became the center of the Hasidic movement by the end of the 18th century. Still, other sects were prominent in the city, and in 1844, a Reform synagogue was erected.

The first Zionist organizations were organized in the 1880s, which published periodicals and formed youth groups. Jews played a leading role in industry, banking and commerce throughout the latter half of the 19th century. There were also several Jewish doctors and lawyers, but most were still tradesman, such as shopkeepers, artisans and peddlers. A new Jewish hospital, one of the best in Poland, and orphanage were unveiled as well.

Cultural as well as professional life also flourished, with an outpouring of Hebrew and Yiddish literature and the establishment of a Jewish theater. By 1910, the city’s Jewish population had swelled to over 57,000.

With the outbreak of World War I, Lvov saw thousands of refugees arrive in the city, fleeing persecution by the Cossacks. The Russians took the city on September 3, 1914, after the Austrians withdrew. Lvov had remained under Austrian control from 1772 until this time. About 16,000 Jews fled. The Russians withdrew in May 1915, and Austrian rule was eventually dissolved at the end of the war.

Between the World Wars

Once again, the city of Lvov became contested territory, and at the end of World War I, Jews were caught in the middle as Poles and Ukrainians fought for control of eastern Galicia. Pogroms broke out in 1917 and 1918, leaving over 100 Jews dead and hundreds more wounded, as mobs burned and looted homes.

Between the two world wars, Poland remained in control of the city. Despite hardships associated with the government’s anti-Jewish policies and general anti-Semitism, Jewish cultural and educational life flourished in Lvov during this time. The city boasted numerous Jewish schools, including three Jewish high schools with Hebrew language instruction, newspapers, and had about 50 functioning synagogues. The Jewish population neared a high of 110,000 in 1939, one-third of Lvov’s total population, nearly double that of what is was just a short thirty years before. Lvov was also home to the third largest Jewish community in the country.

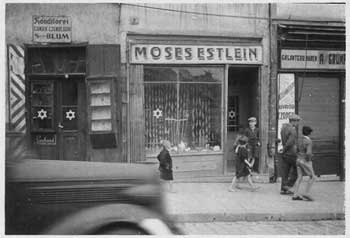

If cultural life flourished, then professional life waned. An economic crisis hit Poland at this time, causing Jewish shops to close. In addition, Jews were fired from their jobs, business licenses were revoked, and lawyers were excluded from public service. By the 1930s, exclusion was not the only form of anti-Semitism, as physical attacks on Jews increased, including stabbings.

The Holocaust

|

|---|

At the start of World War II, Lvov again changed hands, this time falling under the control of the Soviets, who entered the city on September 22, 1939 and immediately annexed it together with the rest of Eastern Galicia. Refugees poured into the city from German-occupied western Poland, and the Jewish population ballooned to more than 200,000. In the summer of 1940, many of them were expelled to the remote regions of the Soviet Union.

Under the Soviets, Lvov underwent a process of “Ukrainization,” whereby Jewish shopkeepers were forced to sell their stocks, and later liquidate their businesses, and synagogues were forced to close down. Schools were instructed to adopt Soviet curriculums, and the Ukrainian language was gradually introduced at the expense of Yiddish. However, about 100,000 Jewish refugees from western Poland gathered in Lvov during this time, which led to widespread Yiddish cultural activity.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, about 10,000 managed to escape from Lvov, together with the retreating Red Army. Germany captured the city on June 30, 1941, and the systematic decimation of the Jewish community began that same day, with nearly 4,000 murdered instantly in pogroms carried out over a four day period by members of the Einsatzgruppe C, German soldiers, Ukrainian nationalists, and the local population, fueled by rumors that Jews had participated in the execution of Ukrainian political prisoners, whose bodies had been discovered in the dungeons of the NKVD (the Soviet political police). The riots finally subsided on July 3, 1941.

On July 8, Jews over the age of fourteen were required to wear a white badge with a blue Star of David on their arms at all times. July 25 to 27 again witnessed mass riots, which left 2,000 more Jews dead. These pogroms became to be known as the Petliura Days.

A temporary Jewish committee was established at the end of July 1941, which comprised of five prominent community leaders. The committee was enlarged in a relatively short time and became a Judenrat (a Jewish council), with Dr. Joseph Parnes serving as the chairman.

The summer of 1941 was a terrible time for the Jews of Lvov – synagogues were destroyed, property was stolen and cemeteries were desecrated. Thousands were sent to off to be used as forced labor in the building of bridges, roads and military training camps for the Germans.

In September, a Jewish police force was set up under the Judenrat, to keep order and ensure cleanliness in the streets where Jews resided, to confiscate valuables at the request of the Germans, and to escort people on their way to forced labor. Parnes, the leader of the Judenrat, was killed by the Nazis at the end of October for refusing to hand over Jews who were then going to be moved to the Janówska work camp. Abraham Rotfeld replaced him.

On November 8, the Nazis published an order on the establishment of the Jewish ghetto of Lvov, which would eventually hold more than 100,000 people. They had until December 15 to pack up their belongings and move into the ghetto. During this time, as Jews began to file into the ghetto, five thousand elderly and sick Jews were killed as they were about to cross the bridge on Peltewna Street.

The deportations began soon after, during the winter of 1941-1942 with the Nazis sending thousands at a time to the labor camps at Laszki Murowane, Hermanów, Vinniki, Jaktorów, Kamionka Strumilowa, and Skole. In February 1942, Abraham Rotfeld died, leaving Henryk Landsberg in charge as Judenrat chairman, at the appointment of the Germans.

|

|---|

In March 1942, the Judenrat was forced to hand over lists of Jews who could be sent to work in camps in the East. A delegation of rabbis pleaded with Landsberg and begged him not to cooperate, but Landesberg refused, stating that many more would be killed if refused to hand over the lists. This Aktion began on March 19, and continued until the end of the month. Nearly 15,000 Jews were deported to the Belzec extermination camp, 60 miles to the north in Poland. On July 8, many were also sent to the Janówska labor camp in the northern outskirts of Lvov where most were shot to death by firing squads. On August 10, another mass deportation ensued, which lasted until August 23, and 50,000 Jews were again sent to the Belzec death camp.

In September, the ghetto was sealed, and the Nazis hanged Landsberg and a group of Judenrat members. Eduard Eberson then became head of the Judenrat in Lvov. Toward the end of 1942, the ghetto having been greatly reduced by further deportations, it became to act as more of a labor camp. The ghetto officially became a labor camp in January 1943, called a Julag (Judenlager, or “Jewish camp”). Ten thousand Jews were executed immediately, being that they could not produce a proper employment card. The Judenrat was disbanded on January 30, and most of the remaining members were killed. An Oberjude (chief Jew) was then appointed to serve as a liaison between the ghetto and the Nazis.

By May 1943, another 1,500 Jews had been murdered inside the ghetto and 800 were transported to Auschwitz. The Selektionen process was then speeded up, and only those deemed “vitally important” were permitted to stay. The rest were killed.

The ghetto was liquidated in June 1, 1943. Every avenue of escape was sealed off, and additional police units were called into assist. A small number of Jews managed to launch a few hand grenades and Molotov cocktails and the encroaching German and Ukrainian police forces. They managed to kill nine and wound twenty before the Germans began to set the buildings on fire. During the liquidation, 7,000 Jews were seized and sent to Janówska, where they were immediately murdered, and three thousand were killed in the ghetto itself. It was all over in a day. By the time the Soviets reentered the city in July 1944, only a handful of Jews remained.

Lvov Today

The postwar Jewish population reached a high of 30,000 in 1979. After the war, Jews slowly returned to Lvov but due to religious suppression and anti-Semitism, the Jewish population has dwindled. Many have since emigrated to Israel, Germany and the United States.

Today, about 5,000 Jews reside in Lvov, which is now a part of the Ukraine, and called Lviv in Ukrainian. In 2004, the Jewish community center opened, operated by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which includes a one-room museum with photographs and Judaica. A synagogue exists, called the Bais Aron V’Yisroel Synagogue, led by Chief Rabbi Mordechai Shlomo Bald. The rabbi and his wife helped established the Jewish school, the Acheinu Lauder school, in which about 60 children are enrolled. An orthodox prayer group meets in a building adjacent to the ruins of the Golden Rose Synagogue, which includes a small kosher canteen.

The old walled city of Lvov went virtually unscathed during the war, and today, Old Town, anchored by cobblestoned Rynok Square, is one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sights.

Although relations have remained stable over the years, there is still a strong undercurrent of anti-Semitism in Lvov. Jewish monuments and buildings are frequently vandalized, with anti-Semitic epithets smeared across fences and walls.

Jewish Tourist Sites

Bais Aron V’Yisroel synagogue was built in 1924 designed by architect Aba Kornbluth. It is a modest yellow building designed in the tradition of Renaissance synagogues of the 17th century. The Nazis used the building as a stable and the Communists later converted it into a warehouse. It was returned to the Jewish community in 1989, and recently underwent a major interior renovation under the direction of architect Aron Ostreicher, known for his projects restoring synagogues around the world. The synagogue was rededicated in 2007.

The Nazis burned down the Golden Rose synagogue in 1942. Part of the building’s northern wall remained in tact and now bears a plaque, written in English, Hebrew and Ukrainian. Like the synagogue, little remains of the old Jewish quarter of Lvov. In 1941, the Nazis destroyed both the Reform synagogue, built in the 13th century, and the Hasidic Grand Synagogue, built in the 17th century. A small plague marks the spot of where the Reform Synagogue once stood.

A small synagogue built in the mid-19th century does remain. It survived World War II, and was the city’s only functioning synagogue from 1945 until 1962, when it was closed by the Soviets. The former Jewish Hospital, built in 1904, also survived, and still functions as a gynecological hospital.

Other sights in the city include a memorial to the victims of the Lvov ghetto, which includes a large statue depicting a Jew raising one hand to the heavens and one hand clenched in protest at one end, and a menorah bearing an inscription that says “remember and keep in your heart” at the other. About 15 minutes drive from the city sits the Janówska labor camp.

Sources: Fellner, Dan. “The Jewish Traveler: Lvov.” Hadassah Magazine (April 2008).

Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. “Lvov.”

The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life: Before and During the Holocaust. “Lwow.”

Photo credits: Top photo (panoramic view of Lvov & Lvov’s old city walls) - courtesy of Jan Mehlich on Wikipedia

Holocaust Photos - H.E.A.R.T.