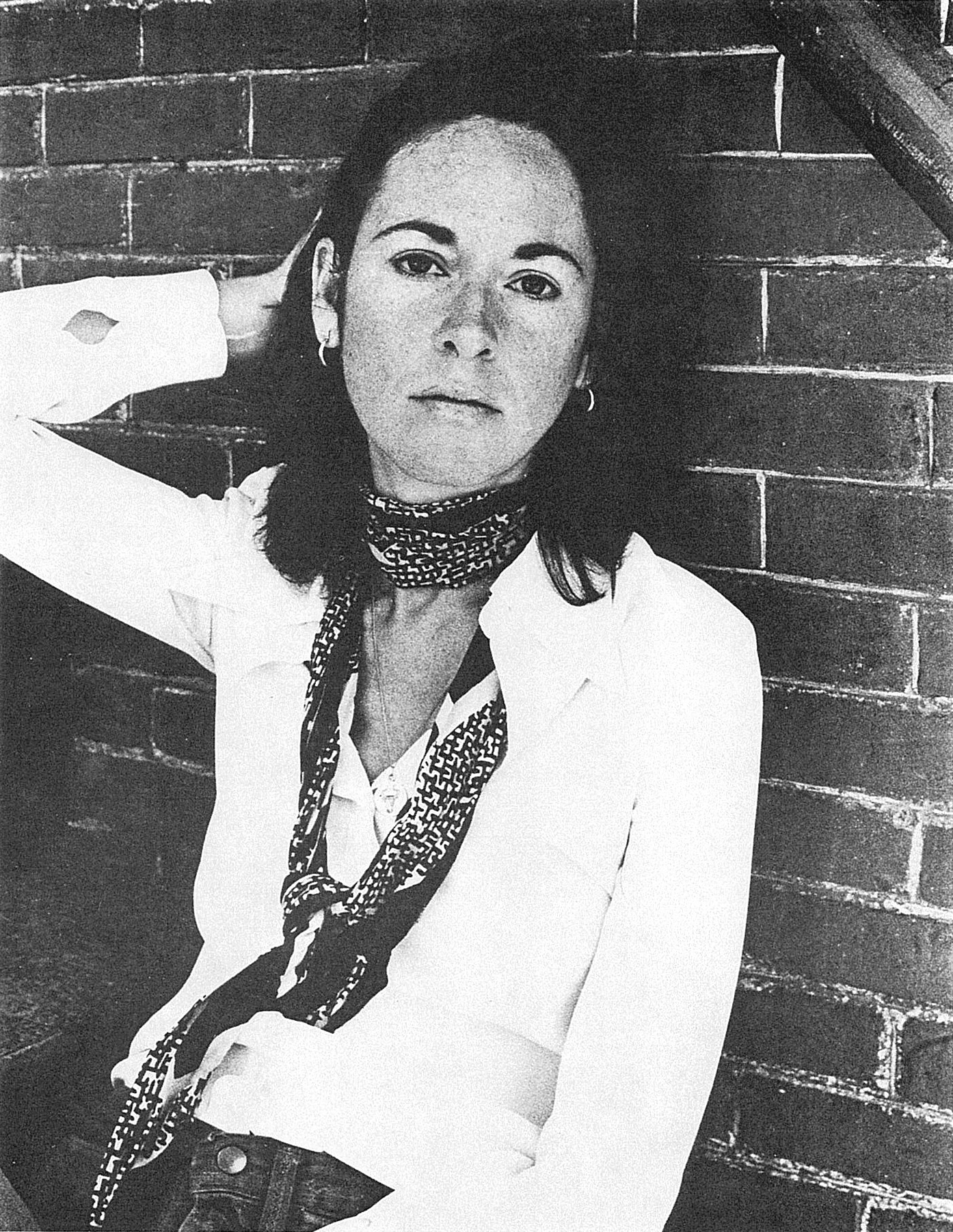

Louise Glück

(1943 - 2023)

Louise Elisabeth Glück, the recipient of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature, was born on April 22, 1943, in New York City to a father who never acted on his dream of being a writer and a mother who fought to attend Wellesley College before women’s education was accepted. Glück’s paternal grandparents, Hungarian Jews, emigrated to the United States, where they eventually owned a grocery store in New York. Glück’s father went into business with his brother-in-law and, together, achieved success when they invented the X-Acto Knife.

From an early age, Glück received from her parents an education in Greek mythology and classic stories such as the legend of Joan of Arc. She began to write poetry at an early age.

Illness

As a teenager, Glück developed anorexia nervosa, which became the defining challenge of her late teenage and young adult years. She has described the illness, in one essay, as the result of an effort to assert her independence from her mother. Elsewhere, she has connected her illness to the death of an elder sister, an event that occurred before she was born.

During the fall of her senior year at George W. Hewlett High School, in Hewlett, New York, she began psychoanalytic treatment. A few months later, she was taken out of school to focus on her rehabilitation, although she still graduated in 1961.

Of that decision, she has written, “I understood that at some point I was going to die. What I knew more vividly, more viscerally, was that I did not want to die.” She spent the next seven years in therapy, which she has credited with helping her to overcome the illness and teaching her how to think.

As a result of her condition, Glück did not enroll in college as a full-time student. She has described her decision to forgo higher education in favor of therapy as necessary: “…my emotional condition, my extreme rigidity of behavior and frantic dependence on ritual made other forms of education impossible.”

Instead, she took a poetry class at Sarah Lawrence College and, from 1963 to 1965, she enrolled in poetry workshops at Columbia University’s School of General Education, which offered programs for non-traditional students. While there, she studied with Léonie Adams and Stanley Kunitz. She has credited these teachers as significant mentors in her development as a poet.

Career

After leaving Columbia without a degree, Glück supported herself with secretarial work. She married Charles Hertz, Jr., in 1967. The marriage ended in divorce.

In 1968, her first collection of poetry, Firstborn was published. Encyclopedia Britannica observed how Glück “used a variety of first-person personae, all disaffected or angry. The collection’s tone disturbed many critics, but Glück’s exquisitely controlled language and imaginative use of rhyme and metre delighted others.”

Glück experienced a prolonged case of writer’s block, which was only cured, she has claimed, after 1971, when she began to teach poetry at Goddard College in Vermont. The poems she wrote during this time were collected in her second book, The House on Marshland (1975), which many critics have regarded as her breakthrough work, signaling her “discovery of a distinctive voice.”

In 1973, Glück gave birth to a son, Noah, with her partner, John Dranow, an author who had started the summer writing program at Goddard College. In 1977, she and Dranow were married.

In 1980, Dranow and Francis Voigt, the husband of poet Ellen Bryant Voigt, co-founded the New England Culinary Institute as a private, for-profit college. Glück and Bryant Voigt were early investors in the institute and served on its board of directors.

In 1980, Glück’s third collection, Descending Figure, was published. It received some criticism for its tone and subject matter: for example, the poet Greg Kuzma accused Glück of being a “child hater” for her now widely anthologized poem, “The Drowned Children.” Overall, however, the book was well received.

In the same year, a fire destroyed Glück’s house in Vermont, resulting in the loss of all her possessions. In the wake of that tragedy, Glück began to write the poems that would later be collected in her award-winning work, The Triumph of Achilles (1985). Writing in the New York Times, the author and critic Liz Rosenberg described the collection as “clearer, purer, and sharper” than Glück’s previous work. The critic Peter Stitt, writing in The Georgia Review, declared that the book showed Glück to be “among the important poets of our age.”

In 1984, Glück joined the faculty of Williams College in Massachusetts as a senior lecturer in the English Department. The next year she published The Triumph of Achilles (1985) in which she creates her own midrashic interpretation of a story from the Midrash Rabbah and measures her immigrant grandfather’s life against that of Joseph in Egypt.

The same year her father died. The loss prompted her to begin a new collection of poems, Ararat (1990), the title of which references the mountain of the Genesis flood narrative. In 2012, New York Times, critic Dwight Garner called Ararat “the most brutal and sorrow-filled book of American poetry published in the last 25 years.”

Winning the Pulitzer

Glück then followed this collection in 1992 with one of her most popular and critically acclaimed books, The Wild Iris is an entire book in the voice of one of the Hebrew prophets translated to a modern sensibility. Publishers Weekly proclaimed it an “important book” that showcased “poetry of great beauty.” It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1993, cementing Glück’s reputation as a preeminent American poet.

While the 1990s brought Glück literary success, it was also a period of personal hardship. Her marriage to John Dranow ended in divorce and she channeled her experience into her writing, entering a prolific period of her career. In 1994, she published a collection of essays on the theory and practice of poetry, Proofs & Theories (1994), which won the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for Nonfiction.

She then produced Meadowlands (1996), a collection of poetry about the nature of love and the deterioration of a marriage.

Although her poetry shows the strong influence of psychoanalysis and classical mythology, she also draws on Jewish tradition for mythic images and stories. Garner said, “Ms. Glück’s collected poems have a great novel’s cohesiveness and raking moral intensity. This is a poet with a prosecutorial mind: in supple and exact language, she interrogates the world around us. She is fearsome. And fearless.”

Anders Olsson, Chairman of the Nobel Committee observed:

A good example was Vita Nova (1999), which earned Glück the prestigious Bollingen Prize from Yale University. “Although the ostensible subject matter of the collection is the examination of the aftermath of a broken marriage,” her biography from the Poetry Foundation notes, “Vita Nova is suffused with symbols drawn from both personal dreams and classic mythological archetypes.”

In 2001, she published The Seven Ages and, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Glück published a book-length poem entitled October (2004). The poem draws on ancient Greek myth to explore aspects of trauma and suffering.[34] That same year, she was named the Rosenkranz Writer in Residence at Yale University.

Since joining the faculty of Yale, Glück has continued to publish poetry. Her books published during this period include Averno (2006), A Village Life (2009), and Faithful and Virtuous Night (2014). In 2012, the publication of a collection of a half-century’s worth of her poems, entitled Poems: 1962-2012, was called “a literary event.” Another collection of her essays, entitled American Originality, appeared in 2017.

“Honed by inner wounds from the death of an older sister, and by her battle with anorexia, years of psychoanalysis, and study with Stanley Kunitz, Glück’s poetic voice is lyrical yet reticent, cloaking the confessional in the classical,” noted Linda Rodriguez. “Her poetry explores the intimate drama of family tragedies resonating through the generations and the relationship between human beings and their creator.”

Rodriguez added, “she writes with passion restrained by intelligence in a voice of controlled elegance, and luminous mystery.” Rodriguez noted that “her use of myth and story to illuminate the individual heart and the archetypal family, as well as her recurrent attempts to understand God, have led some to call her work cryptic or harsh.”

In 2003, Glück was named the 12th U.S. Poet Laureate. That same year, she was named the judge for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, a position she held until 2010.

In addition to the Pulitzer and Bollingen Prizes, she has received many awards and honors for her work, including the Lannan Literary Award for Poetry, a Sara Teasdale Memorial Prize, the MIT Anniversary Medal, and fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundations, and from the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2008, she was awarded the Wallace Stevens Award, and, in 2015, she received the Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

She received the Nobel Prize in Literature in October 2020 “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” Olsson said, “Louise Glück’s voice is unmistakable.” He added, “It is candid and uncompromising, and it signals this poet wants to be understood.” But he also said her voice was also “full of humor and biting wit.”

Glück lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts where she died on October 13, 2023. She is survived by her son.

Bibliography

Firstborn. – New York: New American Library, 1968

The House on Marshland. – New York: Ecco Press, 1975

The Garden. – New York: Antaeus Editions, 1976

Descending Figure. – New York: Ecco Press, 1980

The Triumph of Achilles. – New York: Ecco Press, 1985

Ararat. – New York: Ecco Press, 1990

The Wild Iris. – Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1992

Proofs and Theories: Essays on Poetry. – Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1994

The First Four Books of Poems. – Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1995

Meadowlands. – Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1996

Vita Nova. – Hopewell, N.J.: Ecco Press, 1999

The Seven Ages. – New York: Ecco Press, 2001

October. – Louisville, Ky: Sarabande Books, 2004

Averno. – New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006

A Village Life. – New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009

Poems 1962–2012. – New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012

Faithful and Virtuous Night. – New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014

American Originality: Essays on Poetry. – New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017

Sources: F. Diehl (ed.), On Louise Gluck: Change What You See (2005);

Dwight Garner, “Dwight Garner’s 10 Favorite Books of 2012,” New York Times, (December 17, 2012);

Linda Rodriguez, Encyclopaedia Judaica, (2nd ed.), © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved;

“Louise Glück,” Poetry Foundation;

“Louise Glück,” Wikipedia;

“Louise Glück,” Encyclopedia Britannica, (October 8, 2020);

Alex Marshall and Alexandra Alter, “Louise Glück Is Awarded Nobel Prize in Literature,” New York Times, (October 8, 2020);

Anders Olsson, “Biobibliographical notes,” The Nobel Prize, (October 8, 2020);

“The Nobel Prize in Literature 2020,” The Nobel Prize, (October 8, 2020).

Photo: Public Domain.