Syria Virtual Jewish History Tour

|

|

See also: The Jews of Syria

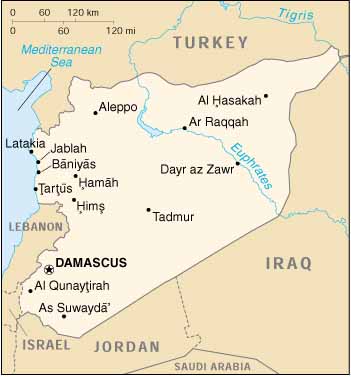

Syria, located in southwest Asia, borders Israel and Jordan to the south, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, and Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Syria, once home to a large and budding Jewish community, has seen its Jewish population dwindle as repressive Islamic regimes control the country. Today, only four Jews are known to be living in Syria.

Learn More - Cities of Syria:

Aleppo | Damascus | Emesa | Euphrates | Hierapolis | Jubar | Naveh | Raqqa | Riblah | Tadmo

Biblical & Second Temple Period

Following the Arab Conquest

Contemporary Period

Jewish Community in Independent Syria

Developments Since the 1970s

Attitude Toward Israel

Biblical & Second Temple Period

For its earlier history see Aram; Aram-Damascus. During the late biblical era, the political history of Syria is somewhat similar to that of Ereẓ Israel, as both territories were either subject to the great powers of the east (e.g., Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia) or disputed by two or more prominent empires. (Under subsequent Roman rule the two districts were often considered one entity, with jurisdiction over the area in the hands of the Syrian governor). During the Hellenistic period, Syria served as the administrative center of the Seleucid Empire, with Antioch as the capital. With the collapse of that empire, the country passed briefly into the hands of the Armenians and was eventually conquered by Pompey (64 B.C.E.). The defense of Syria became strategically vital to the Roman Empire because it was the eastern outpost bordering on the perennial enemy, in the form of the Parthian and subsequently the Sassanid empires. In 616, Syria was briefly controlled by the Persians under Chosroes II and was recaptured by the Byzantines only to fall to the Muslims in 636.

Dating back to biblical times, the Jewish community in Syria developed due to the proximity of the Jewish center in Palestine. Thus, according to Josephus, Ezra was commanded by the Persian Xerxes to appoint judges among the Jews "to hold court in all of Syria and Phoenicia " (Ant. 11:129). During the Second Temple period, the Jewish community apparently thrived, and even Roman governors of Syria were known to fall under the influence of the Jewish multitudes (cf. Philo, Legatio ad Gaium 355 – 367). Similarly, Josephus, in describing the tribulations of the Jews of Antioch, begins by stressing that "the Jewish race, densely interspersed among the native populations of every portion of the world, is particularly numerous in Syria, where intermingling is due to the proximity of the two countries. It was at Antioch that they especially congregated, possibly owing to the greatness of that city, but mainly because the successors of King Antiochus [Epiphanes, 175–164 B.C.E.] had enabled them to live there in security" (Wars 7:43). These Jews therefore flourished and were in a position to send costly offerings to the Temple at Jerusalem. The community was granted citizen rights equal to those of the Greeks (ibid.; cf. Apion 2:39, where these rights were granted by the founder of the city, Seleucus I Nicator), and this probably caused considerable envy of the Jews, which erupted into violence upon the declaration in Palestine of the great war against Rome (66 C.E.). Jewish influence was also felt in Damascus, where a majority of the female Greek population had strong leanings toward Judaism. This, however, did not prevent the Greeks of that city from slaughtering the entire Jewish population of 10,500 with the outbreak of the Jewish-Roman War (Wars 2:561).

Both the proximity to Ereẓ Israel and the great number of Syrian Jews subsequently convinced the rabbis to consider the area similar to Palestine in certain respects, and thus the halakhot pertaining to the land

(מִצְווֹת הַתְּלוּיוֹת בָּאָרֶץ) were often applied to Syria. The Mishnah states that: “He who buys land in Syria is as one who buys in the outskirts of Jerusalem“ (Hal. 4:11); “If Israelites leased a field from gentiles in Syria, R. Eliezer declares their produce liable to tithes and subject to the Sabbatical laws, but R. Gamaliel declares it exempt” (ibid. 4:7). Numerous tannaitic traditions discuss the particular halakhic status of Syria (cf. Tosef., Kelim BK 1:5, Ter. 2:9–13; Av. Zar. 2:8), and it appears that the rabbis differentiated between certain districts in Syria (Tosef. Peah 4:6). Nevertheless, the Jews of Syria probably considered themselves part of the Diaspora, and this would explain not only financial support of the Palestinian rabbis but also the fact that a number of Syrian Jews were brought to Bet Shearim for burial.

Following the Arab Conquest

As far as can be deduced from the writings of Arab historians the Jews of Syria did not occupy a position of prominence at the time of the conquest of the country by the Arabs during the 630s. There is, however, no doubt that they preferred the conquerors, as did most of the population, to the Byzantine rulers. In the history of the conquest related by the Arab historians the Jews are occasionally mentioned among the groups of the population who negotiated with the Arabs; they were included in the surrender treaty of Damascus in 635. Later, when the inhabitants of Tripoli fled to Byzantium, the Arabs placed a Jewish garrison in this important coastal town. With the Arab conquest, the situation of the Jews improved in comparison to the former servitude and religious coercion. The Umayyad dynasty, which chose Damascus as the capital of the Muslim empire, treated non-Muslims with tolerance. As the number of Christians in Syria was far greater than that of the Jews, the Arab authors principally mention the Christian officials and counselors of the first Umayyads; there were, however, several Jews in the royal court of Mu ʿ āwiya. Although the last Umayyads, the descendants of Marwān, emphasized the Muslim character of the kingdom, they did not harass the Jews. With the advent of the Abbasids (750), there was a decisive change in the attitude of the Muslim kingdom toward Jews and Christians – a situation that was acutely felt in Syria. The burden of the taxes was increased and growing pressure was exerted on non-Muslim groups to convert to Islam. During this period the Muslim authorities began to issue decrees against Jews and Christians, e.g., separation from Muslims by wearing distinctive signs on their clothing (see Covenant of Omar ).

|

|

The disintegration of the Abbasid caliphate began in the early ninth century. For a period of four centuries, Syria became the scene of a struggle between various dynasties and the Jews, like the remainder of the population, suffered greatly. The local rulers and the governors of the caliphs who often regained control over Syria were incapable, for example, of preventing the invasion of the Karmatian hordes from Bahrain or of the Byzantines who penetrated into the country on several occasions and devastated it. In spite of this, the tenth century was a period of numerical growth and economic progress for the Jewish population of Syria. Political chaos in Iraq prompted many of its Jews to immigrate to other countries, and a considerable number settled in Syria. The immigrants retained their identity and founded their own synagogues in the towns where their numbers were considerable. The Jews then began to play an important role in commerce and banking, even though most of them were craftsmen. The tenth-century Arab geographer al-Maqdisī wrote in his work that in this land, most of the bankers, dyers, and tanners are Jews.

Immediately after their conquest of Egypt (969), the Fatimids sent their armies to Syria, which they also succeeded in annexing. Their control over Syria, however, was unstable and the northern regions detached themselves from their authority after a short while. This Shiʿite dynasty, which sought to depose the orthodox caliphs of the Abbasid dynasty, displayed tolerance toward the members of other faiths either because this policy was in accordance with their religious outlook or under the force of circumstances. The period of Fatimid rule over southern Syria was a prosperous one for the Jewish communities.

The first vizier of the Fatimids, Jacob Ibn Killis, a Jew who converted to Islam but remained loyal to his former coreligionists, appointed a Jew, Manasseh b. Abraham al-Qazzāz, to head the administration of Syria. He utilized his powers on behalf of the Jews and granted many of them positions in government. His son Aṣiya was also a high-ranking official in the government. At the beginning of the 11th century, the attitude toward the Jews changed for a time when the caliph al-Ḥākim issued various decrees against non-Muslims. In several towns, synagogues were destroyed or converted into mosques. After a few years, however, al-Ḥākim reconsidered these moves and the synagogues were returned to the Jews or new ones were constructed.

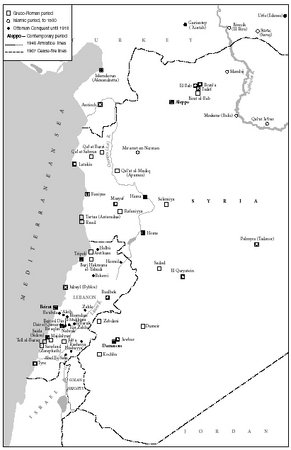

The leading communities in Syria at the time existed in Damascus, Aleppo, and Tyre; there were also smaller communities in Tripoli, Jubayl, Baalbek, Baniyas, Bazā ʿ a, and others. The Jews of Syria maintained regular contact with the Palestine academy and were guided by its leaders in all religious affairs. The communities of Syria themselves produced eminent scholars during the 11th century, among them R. Baruch b. Isaac, who was rabbi in Aleppo during the second half of the century and wrote commentaries on the Gemara, as well as other intellectuals who wrote florid poems in Hebrew.

During the 1070s the Seljuk armies invaded and conquered Syria, with the exception of the coastal strip to the south of Tripoli. The Seljuk conquest brought disaster to the whole of Syria and Ereẓ Israel and the academy was consequently transferred from Jerusalem to Tyre and then during the crusader invasion to Ḥadrak near Damascus, and later to Damascus itself. At the close of the century, the crusaders arrived in Syria and conquered the coastal strip. Many Jews fled to towns in the interior of Syria, which remained under Muslim domination.Benjamin of Tudela, the 12th-century traveler, provides statistics on the number of Jewish inhabitants in the towns of Syria, many of whom he states were dyers. The Jews of Antioch and Tyre also engaged in the manufacture of glass, and other sources confirm that many of the Jews of Tyre earned their livelihood in this industry. Jews in Tyre were also engaged in international commerce.

The spiritual and religious life of the Jews of Syria was concentrated around the academy, which Solomon, son of the Gaon Elijah ha-Kohen, had transferred to Damascus. The academy continued to exist for several generations and its leaders were known as geonim. During the 1140s it was headed by Abraham b. Mazhir and then by his son Ezra, whom Benjamin of Tudela met. These heads of academies were the final authority in all matters pertaining to religious life, and the descendants of the Babylonian exilarchs, who were referred to by the title of nasi, also played a role in the leadership of the Jewish population.

During the 1170s Sultan Ṣalāḥ-al-Dīn (referred to as Saladin by the Christians) succeeded in uniting Egypt and Muslim Syria under his domination and was thus able to conquer considerable territory from the crusaders. Saladin and his successors, who belonged to the Kurdish Ayyubid dynasty, were not inclined to persecute non-Muslims and permitted Jews to return to Jerusalem in 1187 after they had conquered the city from the crusaders. Indeed the situation of the Jews improved during this period as a result of the lenient attitude of the Ayyubids and the economic prosperity of the state, owing to the close commercial ties with European countries, notably the Italian commercial colonies of the coastal towns. The Hebrew poet Judah Al-Ḥarizi, who visited Syria in the late 1210s, mentions a lengthy list of physicians and government officials in the communities of Damascus and Aleppo.

In 1260 Syria was invaded by the Mongols, led by Hulagu Khan. They carried out massacres in several towns, but it appears that Jews, like Christians, suffered less than Muslims. In Arab historians’ reports of the conquest, it is indicated that the great synagogue in the town of Aleppo was one of the refuges which remained untouched by the Mongols and that all the Jews who had escaped to this place were saved. There was no bloodshed in Damascus since the town surrendered to the Mongols. The two largest Jewish communities in Syria thus remained unharmed. The Mongols also advanced into Ereẓ Israel but were defeated at Ayn Jalut (near Ein-Harod) by the Mamluk army coming from Egypt and retreated from Syria (1260). From then until the beginning of the 16th century, the Mamluk sultans ruled Syria. The Mamluks were inclined to accede to the requests of the Muslim theologians and frequently issued decrees against the non-Muslim communities, such as those pertaining to clothing and the dismissal of Jewish (and Christian) officials from government service (1301). The Mamluks, however, were unable to administer their affairs without the assistance of experienced officials and these were therefore restored to their positions after a short while. Yet these decrees intensified conversion to Islam within the non-Muslim intellectual classes.

After the Mamluks conquered Acre (1291) and the other coastal towns which had remained in the hands of the Crusaders, they destroyed them so that they would not provide a foothold in the event of further invasions from the sea. The ancient communities in these towns, such as the large community of Tyre, thus disappeared. The Jews probably settled in Damascus and Aleppo, where from that time the majority of the Jewish population of Syria resided. The deputy of the nagid of Cairo, whose status was recognized by the Muslim authorities, stood at the head of the Jewish community in Syria, as did the nesi’im of the House of David, who were known as exilarchs. On the occasion of the controversy between the kabbalists of Acre and R. David Shimoni during the 1280s, the exilarch of Damascus, R. Jesse b. Hezekiah supported the Maimonidean faction, and in 1286 he issued a ḥerem (ban) against Maimonides’ opponents.

During the second half of the 14th century, there were frequent changes in the leadership of the Mamluk State and certain rulers once more found it necessary to resort to decrees against the non-Muslim communities in order to mollify their subjects; in 1354 the decrees of 1301 (see above) were reintroduced in Syria. One of the officials, the Karaite Moses b. Samuel of Damascus, later expressed his experiences in Hebrew poems, particularly on how he went on a pilgrimage to Mecca in the retinue of a Mamluk minister. Non-Muslim officials were returned to their positions after a short while, but Muslim fanatics occasionally induced the authorities to renew the discriminatory decrees and thus caused Jews (and Christians) much suffering.

At the close of 1400 the Mongolian leader, Timur Lank (Tamerlane), invaded Syria with a powerful army, captured Aleppo, massacred its people, and then plundered Hama and Damascus. Before he returned to Central Asia his troops burned Damascus, while many craftsmen were taken captive and exiled to Samarkand. Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew sources indicate that the fate of the Jews was no different from that of the other inhabitants; many of them were killed or exiled. The Jewish population recovered very slowly from these misfortunes.

During the 15th century, trade in the region prospered once more and European merchants returned to Syria to buy spices and other goods from the Far East. Most Syrian Jews were craftsmen and small merchants, a certain number of whom were living in poverty. Extant information on the size of the Jewish community, which was recorded by Jewish travelers of the late 15th century, confirms its impoverishment during the Mamluk period. According to the writings of R. Joseph de Montagnana, R. Meshullam of Volterra, R. Obadiah of Bertinoro, and an anonymous traveler from Italy, there were about 400–500 families in Damascus (apart from Karaites and Samaritans). The above-mentioned travelers left no data on other communities, with the exception of R. Obadiah of Bertinoro, who points out that there were 100 families in Tripoli. Thus, the Jewish population of Syria consisted of not more than 1,200 families or approximately 7,000 persons.

In 1492, Jews were expelled from Spain and many went to countries like Italy and Turkey before settling in Syria and bringing about a decisive change in the composition and nature of the Jewish community. Once the number of Spanish Jews in the Syrian towns increased, various problems related to the organization of the communities appeared and the process of their assimilation with the native-born Arabized Jews, the Mustarabs, raised considerable difficulties. The language spoken by the expellees, their way of life, habits, and outlook were different from the accepted Jewish way of life in Middle Eastern countries. In the large towns – where they resided in greater numbers – the Spanish Jews established their own communities, with independent synagogues, cemeteries, and battei din. The wide erudition of their rabbis and the relatively large number of scholars among the Spanish Jews helped them to become leaders of Syrian Jewry throughout the eastern part of the Mediterranean.

A new and significant era in the history of Syria started in 1516 with the defeat of the Mamluks by the Ottoman Turks, who had earlier, in 1453, captured Constantinople and put an end to the Byzantine empire. The 400 years of Ottoman rule (until 1917) greatly contributed to shaping politics, administration, economy, and society in the Syrian lands (including Lebanon and Palestine–Ereẓ Israel), particularly during the 19th century.

One of the largest Muslim empires in history, the Ottoman Sultanate, now controlled major Islamic, Christian, and Jewish centers – Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Damascus – as well as Mecca, Medina, and Constantinople-Istanbul. The majority Muslim-Arabic speaking population and religious leaders developed, by and large, quasi-allegiance to the sultan, who was represented by Ottoman pashas, and governors of several provinces – eyalets or vilayets of Aleppo, Damascus, Sidon, Acre, and Beirut. These governors, however, controlled only the major cities and their rural neighborhoods but were periodically challenged by local forces. In the countryside, notably the mountain regions, feudal lords, tribal chiefs, and large families assumed autonomous rule, collected taxes for the sultan, and provided tolerable security. Only from the 1830s – under the brief Egyptian rule (1832–40) and the reformed Ottoman administration – was the country gradually put under central control. The growing security facilitated the expansion of foreign activities, diplomatic, economic, and educational, notably by Russia, France, and Great Britain as well as by various missionary organizations. Their main object was the Christian communities in the Syrian lands, some half a million (out of the total population of a million and a half, mostly Sunni Muslims, and small communities of Alawis, Druze, and Jews – some 30,000 by the mid-19th century). Russia supported the (Greek) Orthodox Arabic-speaking Christians – the largest Christian community; France helped the Catholics, mainly the Maronites on Mount Lebanon; while Great Britain backed the newly established Protestant community as well as the Druze in Lebanon and Syria and the Jews in Palestine.

European economic activities that grew significantly during the 19th century benefited mostly Christians (and some wealthy Muslim and Jewish merchants) but damaged the livelihood of Muslim artisans and traders, members of the traditional middle classes. They and members of the lower classes were also badly affected by the newly introduced Ottoman reforms of the Tanzimat in 1839, 1856, and 1876, namely, regular taxation, mandatory recruitment to the army as well as some reduction in the role of Islam, and equal status granted to non-Muslims, particularly Christians. All these developments – European intervention, the Tanzimat reforms, and periodically provocative Christian behavior – led to Muslim-Christian tension and violence, particularly in Aleppo in 1850 and in Damascus in 1860. In Damascus, thousands of Christians were massacred by Muslims, assisted actively by Druze and passively by Jews. Around the same time, Druze in Lebanon massacred many Christian Maronites in an ongoing attempt to curb their socio-political ascendancy in Mount Lebanon.

As a result of these events, many thousands of Christians emigrated from Syria and Lebanon to more tolerant places, including Europe and the Americas. Many others, who remained in their homes, sought the protection of foreign powers to enhance their separate communal life. Yet, a small number of Christian intellectuals, mostly educated by American missionaries, tried to find a common ground with their Muslim neighbors in the Arabic language and culture and in secular patriotism centered on Syria. This cultural and patriotic movement constituted a first phase of Arab nationalism that emerged in the early 20th century, but initially, it did not attract Muslim intellectuals, let alone Jewish ones.

Some Jews traveled on extended journeys. The strengthening of the ties between the Jews of Syria and Jewish communities in other parts of the empire and the commercial ties as well as the mutual relations between the communities of Syria and Ereẓ Israel resulted in continued immigration of Spanish Jews to Syrian towns. Aside from the two large communities of Damascus and Aleppo, various 16th-century sources mention the continued existence of smaller communities in ʿAyntāb and Alexandretta ( Iskenderun ) in the north of the country and in Hama, Tripoli, Beirut, Sidon, Baalbek, and Baniyas. There were also village settlements in southern Lebanon, to the south of Sidon, where at least some of the Jews engaged in agriculture.

The most important community from both the economic and the cultural points of view was in Aleppo. During the first half of the 16th century, the community was headed by R. Meir Anashikon (Kore ha-Dorot, 33b) and at the close of the century by R. Samuel Laniado. The rabbis of Syria during this period maintained regular contact with the rabbis in Ereẓ Israel and exchanged opinions with them in all religious and legal matters. The influence of the Safed kabbalists was also important, especially in Damascus, where R. Ḥayyim Vital and R. Moses Alsheikh lived for a long time. The teachings of the Kabbalah were propagated with great facility because the Spanish expellees and the first generations of their descendants were carried away by a mood for ecstatic religion. The religious awakening was also expressed in the writing of many homiletical works. Most of the works of the Syrian rabbis were published in Leghorn, Venice, or Istanbul. In 1605, a Hebrew printing press was established in Damascus, but only one book was printed before it closed. At the time there were also intellectuals among the Jews of Syria who wrote secular poems in Hebrew; aside from R. Israel Najara no other poet of any stature appeared.

The proponents of Shabbateanism succeeded in winning followers in the communities of Syria, and Shabbetai Zvi found many fervent supporters among them. Nathan of Gaza went to Damascus and Aleppo, and even after Shabbetai Zvi’s conversion, he pursued his activity and received support from within these communities. Due to Aleppo’s extensive commerce, Jewish merchants from European countries settled there and by their contributions enabled scholars to devote their lives to the study of the Torah. The literary activity of the rabbis of Aleppo continued as before and for a long time was led by the members of the Laniado family. In the large community of Damascus, however, there were also rabbis who were universally recognized as reliable authorities; these included R. Mordecai Galanté (at the close of the 18th century) and his son R. Moses Galanté.

During the second half of the 18th century, there was a great decline in the trade of Aleppo, but on the other hand, a wealthy class of bankers emerged among the Jews of Damascus, favored by the authorities and playing an important role in the development of community life. During the middle of the 18th century, Saul Farḥi was the banker ( ṣarrāf ) of the governor of Damascus; his son Ḥayyim succeeded him and helped organize the Turkish defenses during Napoleon’s siege of Acre (1799). He played an important role in Jazzār Pasha’s government in Acre until he was killed in 1820 on the order of ’Abdallah Pasha.

During the 1830s, the Jewish bankers were led by Raphael Farḥi, brother of Ḥayyim Farḥi, who skillfully protected their positions. The Jewish community in the mountains of Lebanon prospered during this period, particularly in Deir el-Qamar and Ḥāsbayya. In 1832 Ibrahim Pasha, the son of Muhammad ’Ali of Egypt, conquered Syria and introduced modern administration in the country. The direction of the finances of Damascus was entrusted to a Christian, Hanna Bahri, a rival of Farhi. Even though Ibrahim Pasha abolished the discriminatory laws against non-Muslim communities, he allowed the notorious Damascus blood libel to occur (1840). Once this traumatic event subsided, the life of the Damascus community, as well as that of Jewish communities in the other towns of Syria, improved under the renewal of Ottoman rule. Most of the Damascus Jews earned their livelihoods in various crafts, and a small class of wealthy Jews engaged in the wholesale and international trade of Persian and local products, as well as in the leasing of taxes. Christians periodically devised more blood libels against the Jews, but with little effect. During the 1860 events, the Jewish community of Syria-Lebanon was affected in two ways: in Damascus Christians accused Jews of assisting the rioters and enriched themselves by purchasing the looted property after it was plundered. Some Jews were indeed imprisoned as a result of these accusations until their innocence was proven. In the mountains of Lebanon Jewish communities in Druze villages, such as Deir el-Qamar and Ḥāsbayya, were liquidated.

The end of the 19th century saw a considerable decline in the economic conditions of the Jews in Damascus. Local industries were ruined due to the growing importation of European goods and the opening of the Suez Canal, in particular, which dealt a severe blow to the trade with Persia through the Syrian Desert. Many Jews from Damascus and other places settled in Beirut, which became a large town and a commercial center. Others immigrated overseas, particularly to the Americas. In Damascus, adherence to the values of Judaism was greatly weakened and attempts at the turn of the century to maintain Hebrew schools were unsuccessful. In contrast, the Orthodox Jews of Aleppo kept their traditional educational institutions and a Hebrew press was also established there in 1865. The difference between these two Jewish Syrian communities was also reflected in their attitudes toward the resettlement of Ereẓ Israel. While many of the Aleppo Jews immigrated to Ereẓ Israel and became an active element in its reconstruction, the presence of the Jews of Damascus was almost imperceptible.

After World War I there were three large communities in the French protectorates of Syria and Lebanon: Damascus, Aleppo, and Beirut. In the first two communities, there were about 6,000 Jews, and in Beirut about 4,000, while in the other small communities, there were about 2,000 persons. There was little public activity among the Jews of Syria. From 1921, a fortnightly newspaper in Arabic, al- ʿ Ālam al-Isrā ʾ īlī, was published. In 1946, its name was changed to al-Salām (Peace).

Contemporary Period

|

After World War I, with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Syria became, in 1918, a semi-independent state under the leadership of Amir (later King) Faysal, the son of the Sharif of Mecca and commander of the 1916 Arab revolt against the Turks. He worked to create for the first time a Syrian-Arab national community, where Muslims and non-Muslims could live as equals. He also acknowledged the Jewish national home in Ereẓ Israel and in 1919 reached an agreement on this issue with Chaim Weizmann, head of the Zionist movement. In 1920, however, Faysal was ousted by a military force dispatched by France, which claimed control of Syria and Lebanon. The League of Nations confirmed this claim and these two countries were put under a French Mandate until World War II. The French endeavored to undermine the Syrian-Arab national community while encouraging local autonomous regions, notably for Druze and Alawis, as well as favoring Christian communities. Jews were treated fairly by the authorities and granted representation in local and regional councils. But they were periodically harassed and some were murdered by Arab nationalists and Muslim fanatics, mainly on account of the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine-Ereẓ Israel. Following Syrian independence (1946) and the establishment of Israel (1948), Jews in Syria were subjected to considerable violence.

The independent republic of Syria was initially governed by nationalist leaders and parties who had struggled against the French Mandate. But these failed to tackle the crucial socio-economic problems of the new state and the rebellious minorities as well as to defeat Israel in the 1948 war. Consequently, these civilian politicians were ousted by three military officers in turn, who dominated Syria until 1954. Returning to power, the veteran conservative parties were challenged by radical-secular parties: the communists, Syrian nationalists (PPS), and Ba’thists, who also competed for influence among military officers. These circumstances, compounded by threats of a pro-Soviet or pro-Western takeover, respectively, led Syria in 1958 to create a union with Egypt, the United Arab Republic. However, in 1961, Syria broke away from this union, owing to Egypt’s strict domination and discriminatory economic and political measures.

In March 1963, Syrian army officers organized another military coup in the name of the Ba’th Party. They established a Ba’thist regime which is still in power (2006), having been headed by four successive leaders: Amīn al-Ḥāfiẓ, a Sunni-Muslim officer, until 1966; Ṣalāḥ Jadid, an Alawi officer, between 1966 and 1970, Ḥāfeẓ al-Asad, another Alawi officer, between 1970 and 2000, who was succeeded by his son, Bashār, an ophthalmologist by profession. All four leaders were dictators, each developing distinct domestic and foreign policies. Amīn al-Ḥāfiẓ consolidated Ba’thist rule but was caught in a severe conflict between civilian and military factions. Jadīd developed a Marxist-socialist orientation and a militant anti-Israel line which led to the 1967 war.

|

Ḥāfeẓ al-Asad established for the first time a personal-presidential rule that lasted for 30 years, the longest in the modern history of Syria. He continued the socio-economic revolution of his predecessors and the Alawi domination of the military and security apparatuses that had started with Jadīd. He expanded education and other public facilities but failed to improve the economy and combat corruption. More than his predecessors, he encountered Islamic militant rebellion and put it down with barbaric force, killing some 20,000 people – including women and children – in the city of Hama (1982). Earlier, he joined Egypt’s president, Anwar Sadat in attacking Israel in 1973, but was badly defeated. Subsequently, he tried to maneuver between the Soviet Union, Syria’s military supporter, and the U.S., Israel’s ally. In the 1990s, Asad entered a peace process with Israel with intense American mediation, but peace was not reached after all.

Hafez Asad died in June 2000 and was succeeded by his son Bashār, who reversed several policies and gains of his father. He aborted some political reforms, failed to improve the economy, and lost control of Lebanon, which his father had managed to turn into a Syrian protectorate.Unrest in Syria began on March 15, 2011, as part of the wider 2011 Arab Spring protests out of discontent with the Syrian government, eventually escalating to an armed conflict after protests calling for Assad's removal were violently suppressed. The war involves several factions. The Syrian Armed Forces and its domestic and international allies represent the Syrian Arab Republic and the Assad regime. Opposed to it is the Syrian Interim Government, a big-tent alliance of pro-democratic, nationalist opposition groups (whose defense forces consist of the Syrian National Army and the Free Syrian Army). Another faction is the Syrian Salvation Government, a coalition of Sunni Islamist rebel groups headed by Tahrir al-Sham. Independent of all of them is the de facto autonomous territory of Rojava, whose armed wing is the mixed Kurdish-Arab Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Other competing factions include Salafi Jihadist organizations such as the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State (ISIS/ISIL). The peak of the war was during 2012–2017; violence in the country has since diminished, but the situation remains a crisis.

Jewish Community in Independent Syria

Following Syria’s independence and the events leading to Israel’s establishment, Jews in Syria were subject to violent attacks, resulting in many deaths as well as harsh treatment from the authorities. Aleppo in 1947 and Damascus in 1947 and 1948 witnessed many anti-Jewish actions: riots, burning of books and synagogues, bombings of Jewish neighborhoods, as well as killing and looting. Consequently, of about 15,000 Jews in Syria in 1947, only about 5,300 remained in 1957. Most of them left during the 1940s, especially after the 1947 pogroms in Aleppo. Immediately after the establishment of the State of Israel, the stream of Jewish emigration from Syria increased. Most Jews went to Lebanon, but a few were returned to Syria by the Lebanese authorities upon Syrian request.

From 1948, the condition of Syrian Jewry continued to decline. The government issued a number of anti-Jewish laws, including a prohibition on sale of Jewish property (1948) and the freezing of Jewish bank accounts (1953). Jewish property was confiscated, and Palestinian refugees were housed in the dwellings vacated in the Jewish quarters of Damascus and Aleppo. Many Jews were put on trial because one of their relatives had succeeded in escaping from Syria, others were compelled to visit the police station daily, and not a few were imprisoned without trial. In addition, various limitations were imposed on them, in particular, one forbidding them from leaving the country. For a brief period in 1954 Jews were allowed to leave Syria, on condition that they renounce all claims to their property. After the first group had reached Turkey, however, in November 1954, the police forbade others to leave. Immediately after the union with Egypt (United Arab Republic) in 1958, the prohibition on the exit of Jews was again canceled, on condition that they transferred their property to the government. Frozen bank accounts of Jews were also freed. However, shortly afterward the frontiers were again closed to them, and in 1959 trials of those accused of helping Jews to leave Syria took place. In March 1964, a decree was enacted that prohibited Jews from traveling more than three miles beyond the limits of their hometowns.

After the trial of the Israeli intelligence agent Eli Cohen and his public hanging in Damascus (1965), Jews were assaulted. They suffered more during the Six-Day War (1967) and afterward when many were arrested and others attacked by the Muslim population. Jews were murdered in Damascus, Aleppo, and in Qamishli, near the Turkish border, but because of the strict censorship, no precise details were known. Jews made many efforts to leave Syria, and between 1948 and 1961 about 5,000 Syrian Jews reached Israel; in 1968 the number remaining in Syria was estimated at about 4,000. Most lived in Damascus and Aleppo and belonged to the middle classes and the poor.

The few Jews in Qamishli were not always persecuted since they lived among Muslim Kurds, who were not hostile. The economic situation of the remainder of the Syrian Jewish community worsened. The wealthy generally succeeded in escaping, sometimes even with their capital. The Zilkha Bank in Damascus and the Safra Bank in Aleppo were closed, the former by a government order in 1952.

Most of the Jewish educational institutions were closed. In 1968 only one school, which belonged to the Alliance Israélite Universélle, functioned in Damascus. The Jews of Syria had no nationwide community organization, and each community had its own governing committee.

Developments Since the 1970s

Approximately 4,000 Jews remained in Syria, of whom 2,500 were in Damascus, 1,200 in Aleppo, and 300 in Qamishli. After the Yom Kippur War, the conditions of the Jews in Syria continued to be grim; the Syrian Jewish community was completely cut off from the outside world. The first attempt to break this isolation and escape was undertaken by four young Jewish women, all from Damascus – three sisters, Tony, Laura, Farah Zaybak, and Eva Saad. They were raped, tortured, and then murdered, and their bodies were brought to the Damascus ghetto on March 3, 1974. A week later the corpses of two Jewish boys who had also tried to escape were discovered near the place where the girls had been murdered. Following worldwide protests, the Syrian authorities, anxious to cover up the atrocity, arrested two prominent young members of the Syrian Jewish community, Yosef Shaluh and Azur Zalta, and charged them with murder and smuggling. Moreover, in an attempt to cut all means of escape, 11 Jewish mothers whose children had managed to escape in previous years were arrested, tortured, and interrogated for three successive days in order to extract from them the names of those who had helped their children to leave the country.

On July 3, 1974, an International Conference for the Deliverance of Jews from Middle East Lands, with representatives of 30 nations, convened in Paris at the initiative of the French Council, under the chairmanship of Alain Poher, president of the Senate of France. He called on the Syrian government to comply with the Universal Declaration on Human Rights and to put an end to discrimination against its Jews. The situation, however, continued to be oppressive, with a total ban on Jewish emigration. Even permission for rare cases to go abroad for medical treatment was canceled and Jews had to obtain special permission from the secret police to travel for more than 3 miles from their home. They were frequently searched by the secret police and held for interrogation and torture. A special branch of the secret police oversees the enforcement of anti-Jewish enactments.

Following the peace negotiations between Israel and Egypt, the situation of the Jews did not change much. Agents of the Mukhābarāt, the Syrian secret police, attended synagogue services, possibly also to protect Jews against maltreatment by Muslim fanatics.

At the end of the 1980s, the Jewish population of Syria had declined from about 4,000 in 1983 to about 1,400: 1,180 in Damascus, 150 in Aleppo, and 125 in Qamishli. For virtually the whole of Asad’s period, there was no change in the position of the Jewish community. It was denied basic human rights and civil liberties. Mail, telephone, and telegrams were monitored by the Jewish Division of the Secret Police, which kept them under constant surveillance, subjecting them to search and arrest without warrant. Sales of property were prohibited unless a replacement was being acquired; property belonging to deceased Jews with no surviving family was expropriated without compensation. Identity cards continued to bear the word Mousawi (Jew), while non-Jews had no religious identification on theirs. The one Jewish school in Damascus (Ben Maimon) and the one in Aleppo (Samuel) were both supervised by Muslims and were allowed to teach only biblical Hebrew, limited to two hours a week. Contrary to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to which Syria was a signatory, and unlike the rights granted to other Syrian citizens, the Jews were prohibited from emigrating. Except for six months in 1992 (see below), only a few Jews were permitted to travel abroad for medical or business reasons. In addition to paying bribes, large monetary deposits were required and family members had to be left behind, to guarantee the traveler’s return.

The Mukhābarāt arrested and imprisoned several Jews, without charge or trial, for allegedly attempting to leave Syria or for “security offenses.” These prisoners were exposed to torture and deprivation of food, clothing, and medicines. Typical of these were the brothers Elie and Selim Swed of Damascus, held for two years without anyone knowing of their arrest. Subsequently, in 1991, a form of “military trial” was held, where no charges were published and their lawyer was prohibited from addressing the “court.” They were sentenced to 6½ years in prison, but were released in April 1992. Earlier, in December 1983, 25-year-old pregnant Lillian Abadi of Aleppo and her young daughter and son were brutally murdered and mutilated in their home. Other Jewish families received threats, but no definitive motive for the killings was ever established and nobody was charged. Nevertheless, the Jewish community believed that if the Asad regime was deposed, their treatment by any successor would be even harsher.

The custom of using Shabbat Zakhor as the Sabbath for Syrian Jewry, which originated in 1975 in Toronto, Canada, spread to synagogues throughout North America and other countries, highlighting the plight of Syrian Jews, which, over the years, had been substantially ignored by mainline national and international Jewish organizations.

Criticism of the Syrians’ treatment of its Jewish citizens was later raised by several world governments, including Canada, the U.S., and France. The issue was brought before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. In January 1992, for the first time in responding to the UN body, the Syrian government issued a detailed “accounting” of the “well-being of its Jews,” including a listing of students in educational institutions, places of residence outside the ghettos, and occupations of Jews. During the Asad “re-election” campaign of 1992, the Jewish community was obliged to parade in his support, bearing banners in Hebrew – the first time that language had been permitted to be used in public.

During Syria’s participation in the Madrid Peace Conference in 1992, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker announced that Syrian Jews would be permitted to travel abroad. This change initially did not mean a right to emigrate. The “right to travel” was granted to individuals only under the strict control of the Mukhābarāt rather than through the normal channels always available to other Syrians to obtain passports. Permits, when granted, stated that “…the Jew X…” was permitted to travel, and the fortunate applicants were obliged to purchase return tickets.

A large number of Jews, about 2,600, managed to leave in 1992 and joined families in Brooklyn, New York, although some went to other countries. In the U.S., the new arrivals were welcomed by the well-organized long-standing Syrian community. However, the U.S. refused to admit them as refugees, but only as “visitors.” Thus, they were denied the governmental resettlement facilities available to immigrants, placing a heavy burden on Jewish communal resources with respect to housing, education, and employment. By 1994, 3,565 Syrian Jews had immigrated to the U.S. The rest went to Israel, including the chief rabbi of Damascus. In 2005, few Jews remained in Syria: according to unofficial figures, fewer than 250. By 2014 approximately 17 Jewish individuals lived in Syria, all residing in Damascus.

In May 2014, President Bashar Assad’s forces destroyed the 400+-year-old Eliyahu Hanabi Synagogue in the Jobar neighborhood of Damascus. The synagogue dated back at least to the Middle Ages and was razed to ruins. It is believed that the synagogue was built on top of the cave where the Prophet Elijah hid from people who wanted him dead. During the Middle Ages, it served a populous Jewish community and was converted after Israel’s founding into a school for Palestinian refugees.

The last Jews living in Aleppo, Syria were rescued in a secret mission, the details of which were revealed on November 8, 2015. Seven members of the Halabi family were rushed from their home, in a rescue facilitated and financed by American businessman Moti Kahana. Kahana had heard from local sources that ISIS-affiliated forces were closing in on the family and would soon know where they lived, so he hired “handlers” to help them escape. When members of the Halabi family were first awoken early one morning to hard banging on their front door, they thought that either Assad’s forces or ISIS militants were about to burst into their home to arrest them, or worse. They were hurried into a bus and told that they were being taken to New York City. All family members received fake passports from their handlers, who lied at checkpoints and said that the family was just a group of refugees looking for safety in the country’s North. After a harrowing 36-hour car ride, the Halabi family wound up in Turkey, where Moti Kahana was awaiting their arrival with a rented house and supplies for them. The family decided to make aliyah and move to Israel but one of the older daughters, Gilda, had converted to Islam to marry her husband three years prior. Upon investigation, the Jewish Agency decided that since Gilda had converted to Islam to marry her husband, she was not eligible to make aliyah. The Jewish Agency took the matriarch of the Halabi family as well as her two unmarried daughters to Israel, but Gilda, her husband, and their three children were forced to stay behind in Turkey. When the lease on the home Kahana rented was up and they ran out of supplies, Gilda and her family had no choice but to return to Syria.

The Central Synagogue in Aleppo, Syria, sustained minor damage to a corner wall when caught in the crossfire between groups of Syrian militants in early February 2016. Syrian humanitarian organizations contend that the damage was most likely caused by shelling. The Synagogue remained standing despite the damage, but the building remains in danger as long as fighting continues around it.

The Jerusalem Post reported that four Jews remained in Damascus (two women and two men) after the president of the Jewish community died in September 2022.

Attitudes Toward Israel

Relations between Syria and Israel were marked by political and military tension from the start. Syria’s hostility toward Israel was more extreme than that of other Arab states for the following reasons: its ideology of Arab nationalism and its declared aim of destroying Israel and retrieving Palestine. These notions became more influential with the ascension of the Pan-Arab Ba’th Party to power in 1963 and its tendency to achieve a central position in inter-Arab relations.

Also, the struggle for power in Syria sometimes found expression in the instigation of clashes on the border with Israel. The 48-mi. (77 km.) border between Israel and Syria differed from Israel’s frontiers with other Arab states. The Syrian forces on the Golan Heights had topographical superiority over the Israel villages in the Hula and Jordan valleys, which also enabled them to dominate the sources of the Jordan River leading into Lake Kinneret.

The 1949 Armistice Agreement between the two countries created demilitarized zones along the major portion of the border, and the struggle over the status of these areas was a constant source of military conflict. The Syrian army was the only Arab force that succeeded in the 1948 war in capturing territories originally apportioned to the State of Israel in the UN Partition Plan. Syria intended to keep these territories, while Israel demanded the complete withdrawal of Syrian forces up to the international border as a condition for signing the armistice agreement. Following a suggestion by Ralph Bunche, the UN mediator, a compromise had been reached: those areas evacuated by the Syrians (as well as additional areas in the sector of Ein Gev and Dardara that Israel held) would become demilitarized zones in which the presence of armed forces of both sides [would]… be absolutely forbidden and no activity of semi-military forces [would]… be permitted

(Israel-Syrian Agreement on a General Armistice, Article 5 (a), V). On both sides of the demilitarized zones were defined areas in which the maintenance of defensive forces was permitted (Article 6); the nature of these forces was defined in an addendum to the agreement; it also assured the revival of normal civilian life in the demilitarized zone, including the return of civilians and the establishment of a local police force (Article 5 (e), V); and a Mixed Armistice Commission was established to supervise the agreement (Article 7).

The question of the three demilitarized zones – northern, central, and southern – was a point of military and political contention between Israel and Syria. Israel viewed them as areas under her sovereignty, in which she was free to implement any civilian activity, the only limitation being the above-mentioned military one. Syria, on the other hand, claimed that the sovereignty over these areas was still undecided and protested Israel’s right to carry out civilian activities without the approval of the Mixed Armistice Commission and Syria’s agreement. Moreover, Syria attempted to prevent any such activity, especially agricultural work, and water projects, both by means of military attacks and by presenting complaints to the Mixed Armistice Commission and the UN Security Council. Syria succeeded in gaining control over part of the demilitarized zones, such as al-Ḥimma (after killing seven Israel police in April 1951), the Banyas slopes, the area between the Jordan River and the international border to the east, and on the northeastern shore of Lake Kinneret. A Syrian attempt to gain control over a piece of Israel territory outside the demilitarized zones (near the entrance of the Jordan into Lake Kinneret) in March 1951 was repulsed after a fierce battle at Tel al-Muṭilla. Israel’s protest to the Security Council over these moves, like its protests against other Syrian aggressive actions later on, did not succeed in bringing about a denunciation of Syria in the United Nations.

The military and political struggle over the Israel-Syrian border centered on four issues: (1) Cultivating agricultural areas in the demilitarized zones. Each time Israeli farmers attempted to cultivate land that the Syrians claimed belonged to local Arabs, Syrian forces interrupted their activity by firing from outposts that overlooked Israeli territory, and sometimes major incidents developed, especially in the southern demilitarized zone. On the night of Jan. 31, 1960, units of the Israel Defense Forces carried out an action to wipe out Syrian outposts in Khirbat Tawfīq in the southern zone, but the harassment of Israeli farmers continued, in spite of attempts by the United Nations to mediate the dispute. (2) Fishing in Lake Kinneret. In spite of the fact that all of Lake Kinneret was in Israeli territory and outside the demilitarized zones, the Syrians took advantage of their control over the northeastern shore and attacked fishing boats and police boats in this sector. Israeli units retaliated against Syrian outposts northeast of the lake on the night of December 11, 1955, and against the Nuqayb outpost on March 16–17, 1962. The most serious incident in this sector was on Aug. 15, 1966, when Israeli police boats were attacked and, in retaliation two Syrian planes were shot down over the lake. Periodically, Israel would provoke Syria to attack boats in order to carry out fierce punitive actions against Syrian positions. (3) Development projects in the demilitarized zones. When Israel began a project to drain Lake Hula in 1951, Syria objected to the implementation of works in the central demilitarized zone, claiming that they provided Israel with a military advantage and that some of the work was done on lands that belonged to Arabs. Armed clashes in March and April 1951, followed by deliberations in the Security Council, led to a stoppage of the work and Israel’s leaving the Mixed Armistice Commission. Work was renewed in June 1951 after the chairman of the Armistice Commission ruled that these activities did not constitute a breach of the Armistice Agreement and Israel agreed to avoid using Arab lands; the drainage project was completed in 1957. In September 1953, Israel began digging a canal in the demilitarized zone near the Benot Ya’akov Bridge, as part of the plan for the Jordan-Negev Water Carrier. The Syrians again objected, claiming that this constituted a change in the status of the demilitarized zone, and following its complaint to the Security Council, Israel was requested to stop these activities. Israel then abandoned the original plan and in 1959 began work on the Kinneret-Negev Water Carrier. (4) The National Water Carrier. Some Arab states tended initially to accept the principle of sharing with Israel the waters of the Jordan according to the suggestion made by President Eisenhower’s special envoy, Eric Johnston, in 1953. But the program was finally rejected by the Arab League in October 1955. This rejection was influenced by Syrian pressures to prevent Israel’s economic development, despite the fact that Syria was apportioned a good amount of water from the Jordan and Yarmuk rivers. When Israel was about to complete the National Water Carrier in 1964, the Syrian Ba’th government demanded that the Arab states declare war in order to prevent the implementation of the project. Syria’s demand was rejected by the Arab Summit Conference in January 1964, which decided instead to adopt an alternate plan and divert the headwaters of the Jordan. Syria’s role in the diversion plan was to absorb the waters of the Ḥaẓbani (which flowed from Lebanon), combine them with the flow from the Banyas sources, and direct them into the dam that would be built on the Yarmuk River on the Syrian-Jordanian border. Syrian efforts to prevent Israel from also using the Dan River sources led to serious border incidents in November 1964. Israeli attacks against the Syrian diversion works in 1965–66 eventually stopped the diversion project.

Syria was the first Arab state to support the terrorist activities of the Palestinian organization Fatah, starting in 1965. After the radical wing of the Syrian Ba’th Party – headed by Ṣalāḥ Jadīd – assumed power in February 1966, Syrian support for Fatah and other terrorist organizations increased; most of their actions were carried out across the Jordanian and Lebanese borders in order to prevent retaliatory action by Israel against Syria. The ideology of the Syrian Ba’th government called for a popular liberation war

against Israel.

The deterioration of Syrian-Israeli relations reached a climax on April 7, 1967, in land and air battles during which Israel downed many Syrian planes. Syria's aggressive propaganda, carried on with the support of the Soviet Union, was a decisive factor in the developments leading to the Six-Day War (1967). Even after the Six-Day War, and the occupation of the Golan Heights by Israel, Syria did not abandon the principle of a popular liberation war,

and continued to provide material and political support to the Palestinian terrorist organizations.

Syria rejected the November 22, 1967, Security Council resolution (242), namely, the notion of a peaceful settlement of the Arab-Israel conflict. This extremist position did not change officially when General Ḥāfiẓ al-Asad assumed power in November 1970, although his domestic and foreign policies were in fact more pragmatic than those of his predecessor. The deployment of Israeli troops on the Golan, some 55 km. from Damascus, induced Asad to be cautious and seek a political settlement with Israel. But this strategic predicament also motivated him to try and retrieve the Golan by force. Indeed, in October 1973 he joined Egypt’s President Sadat in launching a military offensive against Israel. Syrian troops were able to capture the entire Golan Heights in several days before they were badly defeated and repulsed.

In October 1973, Syria accepted UN Security Council resolution 338, which included UN Resolution 242 and the principle of peace with Israel in exchange for territories occupied by Israel in 1967 (and 1973). Subsequently, Asad suggested – mainly in interviews with U.S. media – a peace agreement

(in fact a non-belligerency agreement) with Israel in exchange for the Golan and the settlement of the Palestinian problem. Israel ignored this offer, but in 1976 reached a tacit agreement with Syria, with U.S. mediation, regarding the deployment of Syrian troops in Lebanon, following the eruption of its civil war.

Yet Asad’s predicament visà-vis Israel grew further after Sadat signed the Camp David Accords (1978) and the peace agreement (1979) with Menachem Begin, Israel’s new prime minister, and after Israel officially annexed the Golan Heights in 1981. Asad then adopted a doctrine of strategic balance with Israel, obtaining massive military aid from the Soviet Union, but failing to reach his ambitious goal. Asad sought to improve relations with the U.S., and during the 1990 Kuwait war, he dispatched military units to join the American-led coalition that attacked the Iraqi army.

Accepting U.S. suggestions, Asad moderated his position and agreed to attend the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference without pre-conditions and to direct negotiations with Israel. Peace negotiations were indeed conducted with active U.S. moderation for some eight years, and in late 1999–early 2000 Syria and Israel almost reached a peace agreement. Asad died in June 2000 and his son Bashār succeeded him and expressed time and again his readiness to resume negotiations with Israel without pre-conditions. But Israel, backed by the U.S., rejected his suggestions due inter alia to his open support of Hezbollah and Hamas, Syria’s continual occupation of Lebanon, and, from Washington’s point of view, Bashār's vehement opposition to America’s intervention in Iraq and his indirect help to the Iraqi insurgents.

For most Israeli Jews there exist two more reasons to oppose peace with Syria. They refuse to give up the Golan Heights and cannot forget the harsh mistreatment of Jews in Syria since its independence.

The prospect of peace became more remote when the civil war began in Syria. After seeing Iranian and Hezbollah forces infiltrate areas near Israel’s northern border, most Israelis realized giving up the Golan could put their worst enemies on their doorstep. Israel subsequently began to regularly bomb positions in Syria to prevent Iran and Hezbollah from establishing permanent positions, smuggling weapons, and building arms factories.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu admitted to Israeli involvement in the Syrian conflict for the first time on December 1, 2015. Netanyahu told reporters at a press conference, “We occasionally carry out operations in Syria to prevent that country from becoming a front against us. We also do everything to prevent weapons, particularly lethal ones, being moved from Syria to Lebanon.”

In 2017, the IDF began regularly supplying food, fuel, money, and medical necessities to Syrian rebels near the border of the Golan Heights as part of a strategy to prevent hostile forces (ISIS, Hezbollah, Iran) from gaining a foothold in the area. The IDF maintains regular communication with these rebel groups and has established a military command unit to oversee aid to the rebels, including salaries for fighters. The commander of a small organization of Syrian rebels known as the Fursan al-Joulan group, who have been working with Israeli security officials in multiple capacities since 2013, stated that they are given approximately $5,000 per month from Israel. (See Military Threats to Israel: Syria.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Schuerer, Gesch, 3 (1909), 10f.; E.G. Kraeling, in: JBL, 51 (1932), 130–60; B.Z. Luria, Ha-Yehudim be-Suryah (1957); Ashtor, Toledot; idem, in: HUCA, 27 (1956), 305–26; Rosanes, Togarmah; Mann, Egypt, 1 (1920), 19ff., 27ff., 72ff.; Mann, Texts, 1 (1931), 49–54; 2 (1935), 201–55; S.W. Baron, in: PAAJR, 4 (1933), 3–31; S.D. Goitein, in: Zion, 1 (1936), 79–81; Y. Ben Zvi, in: Tarbiz, 3 (1932), 436–79; M. al-Maghribi, in: Majallat al-Majma ʿ al- ʿ Ilmī al- ʿ Arabī, 11 (1929), 641–53; N. Robinson, in: J. Freid (ed.), Jews in Modern World, 1 (1962), 50–90; T. Petron, Syria (1972); J.M. Landau, "An Arab Anti-Turkish Handbill," in: Turcica, 9:1 (1977), 215–24; idem and M. Maoz, "Yehudim ve-lo-Yehudim be-Miẓrayim u-ve-Sūriyya," in: Pe’amim, 9 (1981), 4–14; J.F. Devlin, Syria: Modern State in an Ancient Land (1983); B. Lewis, The Jews of Islam (1984); J.M. Landau, "Ha-Mekorot le-Ḥeker Yehudei Miẓrayim vi-Yehudei Turkiyyah," in: Pe’amim, 23 (1985), 99–110; M. Ma’oz, Syria and Israel: From War to Peace (1995); A. Levy (ed.), The Jews of the Ottoman Empire (1994), index; idem (ed.), Jews, Turks, Ottomans (2002), esp. 108–18; M.M. Laskier, "Syria and Lebanon," in: R.S. Simon et al. (eds.), The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times (2003), 316–34.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

YNet (May 28, 2014).

Khushbu Shah, “Rescuing the last Jews of Aleppo,” CNN,(November 28, 2015).

“Israel PM admits forces operating in war-hit Syria,” Yahoo News, (December 1, 2015).

“Aleppo synagogue damaged in fighting between Syrian militants,” Jerusalem Post, (February 10, 2016).

Rory Jones, Israel Gives Secret Aid to Syrian Rebels,

Wall Street Journal, (June 18, 2017).

“Syrian civil war,” Wikipedia.

Zvika Klein, “The president of Syria’s Jewish community passed away; only four Jews remain in Damascus,” Jerusalem Post (September 22, 2022).

Photos: Family - http://www.syrianhistory.com/photos/006111.jpg, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Allep Jews - Derounian, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.