Mexico Virtual Jewish History Tour

Colonial Period

Arrivals From Portugal

From Independence to 1900

Immigration and Community Organization (1900–50)

Economy And Social Stratification

Immigration and Anti-Semitism

Zionism

Consolidation of the Jewish Community in Mexico

Social Integration and Identity

Demography

Jewish Education and Jewish Culture

Religious Life

Isla Mujeres

Relations with Israel

When Hernando Cortes conquered the Aztecs in 1521, he was accompanied by several Conversos, Jews forcibly converted to Christianity during the Inquisition of 1492. Conversos, or Anusim, immigrated en masse to La Nueva Espagna (present day Mexico) and some estimate that by the middle of the 16th century, there were more of these crypto-Jews in Mexico City than Spanish Catholics.

Colonial Period

|

There were two kinds of Conversos arriving in the “New World,” first, the Crypto-Jews (also called disrespectfully “Marranos”) who had been forced to convert and continued their traditions in secret and were looking for a better economic situation and a way to evade the persecution of the Inquisition’s Tribunal. Many of those belonging to this group were accused before the Tribunal and their records were kept at the “Archivo General de la Nación” (Mexican National Archive), so that their history can be tracked. Also, there were those who were truly converted and integrated who hid their origin and their blood “impurity.” The latter were the ones that most frequently gave away the Crypto-Jews and were incorporated to the Church structure; remarkable examples, among many others, were Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, Fray Alonso de la Veracruz, and Fray Bernardino de Sahagún.

Following the arrival of the Conversos in the New World, we can divide their history into three periods: from the discovery to the conquest (1492–1519); from 1519 until the establishment of the Inquisition Tribunal in New Spain in 1571; and from 1571 to 1810 during which the Tribunal functioned. The first stage was initially characterized by the abandonment of Spain, owing to the expulsion decree. Many Crypto-Jews and New Christians decided to sail with Columbus and other expeditions in order to discover new routes; they even financed these trips. Some remained in the newly discovered islands, while some returned and motivated others they knew into joining this adventure. Until 1502 the migratory restrictions were minimal. From then on, however, the Crown allowed access to the newly discovered lands only to the descendents of Christians who counted no converts among their ancestors or, in other terms, were “pure blooded” (limpios de sangre), meaning that the children of the Jews, the Moorish, the newly converted, and those processed by the Inquisition were not able to sail in official missions such as that of Nicolás de Ovando in 1502. Yet, beginning in 1511, restrictions became flexible owing to the need to populate the new lands with craftsmen, leading to an increase of the number of Conversos with a professional license as well as of businessmen. The commerce in false documents attesting to “pure blood” increased as well, allowing the sailing of a large number of Crypto-Jews heading toward the “Indias.”

In the second period many Crypto-Jews participated with Hernán Cortés in the conquest of the mainland and in the defeat of the Aztec Empire situated in Tenochtitlan. We know about them because of the process against four of them that took place in 1528: two of the Morales brothers, Hernando Alonzo and Diego de Ocaña, were burnt at the stake and the other two received minor punishments.

During this stage a significant arrival of Conversos took place, mainly from Madrid and Seville. They arrived as soldiers, conquerors, and colonizers. There is information that by 1536 there were in New Spain Crypto-Jewish communities in Tlaxcala and Mérida and there are files and records of the procedure against Francisco Millán, a bartender who sold Sabbath wine to the community and informed on a large amount of correligionists. Along with the development of the mining districts, the Crypto-Jews’ settlements became diversified as well, such as in Taxco, Zacualpan, Zumpango del Rio, Espíritu Santo, and Tlalpujahua (1532), Los Reales del Monte in Pachuca, Atotonilco (1544), Zacatecas (1547), and Guanajuato (1554). By the end of the 16th century some small communities were known in Guadalajara, Puebla, Querétaro, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Michoacán, and elsewhere.

The Conversos lived in specific neighborhoods and on certain streets; some dedicated themselves to the local trade, but they traded also with foreign countries, especially with Philippines. Some of these people ascended the social scale and married “old” Christian Spaniards.

The third stage was initiated in 1571, a time by which the Crypto-Jewish communities were already consolidated. Spain solidified its harsh policy toward Jews by opening an Inquisition office in Mexico City, which accelerated the persecution of the crypto-Jews. Over the course of the colonial period, about 1,500 were convicted of being Judaizers, meaning they observed the Laws of Moses or followed Jewish practices.

A New Christian called Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva (nicknamed “El Viejo” — The Elder) received funding and a concession from the Crown to establish “Nuevo Reino de Leon” in the northeast of Mexico. This was a reward to him for his pacifying the Chichimecas. Approximately 100 Spanish families, most of Crypto-Jewish origin, settled in the town.

Arrivals From Portugal

During these years of economic progress, some Conversos from Portugal arrived; they were descendants of the Jews who had been expelled from Spain. Despite the fact that they had come to Mexico only ten years earlier, in 1589, one of their spiritual leaders, García González Bermejo, was discovered, judged, and condemned to death. In the same period there were some “autos-da-fé,” capable of shocking the whole community of New Christians in Mexico. In 1590, a large number of Crypto-Jews were prosecuted, especially those coming from Portugal and Seville; among them were Hernando Rodríguez de Herrera and Tomás de Fonseca Castellanos. In 1596, 46 Conversos were prosecuted, and as a result a few from the Carvajal family were sent to the stake, among them Luis de Carvajal “El Mozo” (The Young) who had become one of the spiritual leaders of the community. In 1601, 45 Crypto-Jews were sent to trial and, between 1574 and 1603, 115 “judaizantes” were prosecuted. Also Indians were prosecuted, accused of being adept in Judaism, quite possibly converted by their Crypto-Jewish masters so they would not give them away. The proceedings present a clear view of the Conversos’ everyday life, their meetings, the way they practiced their traditions, their occupations, and their active participation within the colonial society. Among their crafts particular notice may be given to the shoemakers, tailors, silver craftsmen, engravers, barbers, doctors, painters, wagon riders, musicians, lawyers, and solicitors.

From 1625 to the end of the 17th century, the migration of the Conversos and their descendants from Spain and Portugal diminished, and the persecution of the wealthy Crypto-Jews increased – actions that benefited the wealth of the Inquisition, which confiscated their assets. The inquisitors prosecuted over 200 people between 1620 and 1650 and from 1672 to 1676 a hundred more. Most of the accused came from Portugal, owing to the separation of the two kingdoms in 1640, which provoked increased persecution of Portuguese by Spain. Typical cases were those of Domingo Márquez, deputy major of Tepeaca in 1644, and Diego Muñoz de Alvarado, who was chief magistrate in Puebla de Los Angeles and accumulated a large fortune to the extent of having his own commercial ships.

The Faith Prosecutions did not stop. In 1646, 46 Conversos were prosecuted and were obliged to make a public “reconciliation” with the Church; in 1647 there were 21; 40 in 1648; and finally, on April 11, 1649, 35 were prosecuted out of which eight were executed by burning. From that moment the reconciliated were deported to the Iberian Peninsula to prevent them from reinitiating their Jewish practices for lack of surveillance. Among the deported were Captain Macías Pereira Lobo, sent to trial in 1662; Teresa Aguilera y Roche, wife of New Mexico’s governor; Bernardo López de Mendizábal, judged in 1662; Captain Agustín Muñoz de Sandoval, sentenced in 1695; and a Crypto-Jewish monk tried in 1706 called Fray José de San Ignacio.

From the beginning of the 18th century through to the achievement of Independence (1821), migration disappeared and religious persecution diminished. The Crown and authorities of New Spain took care to prohibit the reading of books from European encyclopedia writers that had liberal and democratic ideas. By then the assimilation of Crypto-Jews into the society was much greater, causing the loss of Jewish customs and traditions due to the lack of contacts with outside political allies. Oral tradition survived in some cases, albeit deformed, and some objects went from generation to generation without a link to their ritual meaning. Some families did not forget their origins, and such was the case of a university professor, Francisco Rivas, who, by the end of the 19th century, published a journal called El Sábado Secreto (“The Secret Saturday”), in which he declared himself to be a descendant of Conversos from the Colonial period.

To keep from assimilation, the Conversos did not intermarry, and considered themselves superior to their Christian neighbors. Other conversos assimilated in the 19th century, and descendants of the Conversos are often devout Catholic families that light candles on Friday nights, keep meat and dairy separate, and close their businesses on Saturdays. Today, Mexico is home to many Conversos, with sizable populations in Vera Cruz and Puebla.

Despite the fact that the Inquisition ended symbolically as well as physically regarding Judaism, there are still some groups in Mexico that define themselves as Jews descending from the Crypto-Jews. The main congregations identified as such are the ones at Venta Prieta in Pachuca, Hidalgo, and Vallejo – a northern neighborhood of Mexico City. The members of those communities at Venta Prieta and Vallejo, named Kahal Kadosh Bnei Elohim (the leader of the latter in 2005 was Dr. Benjamín Laureano Luna), who have “mixed blood” and Indian features, claim that their genealogy comes from the colonial period. However, there are scholars like Loewe and Hoffman that who conclude that they are not Crypto-Jews but descendants of a protestant Evangelical church called “Iglesia de Dios” (Church of God). When the modern Jewish community got in touch with them in the 1940s, the problem of their inclusion or exclusion into the community arose. On the basis of anthropological studies by Rafael Patai, this community received attention from foreign Jews, who made several trips in order to support and teach them normative Jewish practices. The ambiguity in the relations remains, and the attitudes from the different community sectors are varied, from the religious and cultural acceptance to open rejection.

Many prominent Mexicans claim they are of Jewish descent, referencing their Conversos roots. Besides Presidents Porfirio Diaz, Francisco Madero and Jose Lopez Portillo, renowned artist Diego Rivera publically announced his Jewish roots: "My Jewishness is the dominant element in my life," Rivera wrote in 1935. "From this has come my sympathy with the downtrodden masses which motivates all my work."

From Independence to 1900

When Mexico started its independent life in 1821, the decrees and legislation of the new Republic maintained Catholicism as the sole and official religion, despite the abolition of the Inquisition. Because of the Catholic church’s heavy influence, the nation had fewer than 30 Jewish families as late as the mid-19th century. The few Jews who moved to Mexico in the early 19th century were German. Religious prejudices promoted by the church did not disappear and Catholics kept blaming Jews of “deicide” (God killers). The Mexican governments during the first 50 years of autonomy reached commercial and political agreements with some European companies that belonged to Jews, and it is possible that some of the latter lived temporarily or permanently in the country, though there was no community lifestyle.

At the time of the arrival of Maximilian of Austria as Emperor of Mexico (1864–67), some Jews from Belgium, France, Austria, and Alsace came with his court; they even talked about the possibility of building a synagogue, but the project was not accomplished, so religious services were held in private homes. One of the most outstanding personalities was Samuel Basch, chief surgeon at the Military Hospital at Puebla and personal doctor to the emperor in 1866. It was Basch who took Maximilian’s remains to Vienna and after that published “Mis recuerdos de México” (“My memories of Mexico”). With the end of the empire most of these Jews returned to their countries.

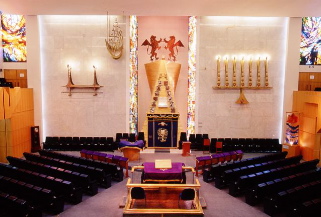

Bet El Synagogue, Mexico City |

Religious freedom was proposed by a generation of liberals by the middle of the 19th century, under the leadership of Benito Juárez who overthrew Maximilian in 1867 and secularized Mexico, seizing church property and banishing the Papal Nuncio. His political and economic modernization project was established in articles 5 and 130 of the 1857 Constitution, which neither affirm religious freedom explicitly nor deny it. This upheaval paved the way for three waves of mass Jewish immigration, the first of which was sparked in 1882 by the death of the Russian Tzar. The exodus was accelerated in 1884 when Mexican President Profirio Diaz invited a dozen Jewish bankers from Europe to move to Mexico and help build its economy. Mexico established its first Jewish congregation in 1885.

During the “dictadura Porfirista” (dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz, 1876–1911), the country was peaceful and foreign investors saw Mexico as a business option. Some foreign companies’ representatives were Jews from France, Austria, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the United States, and Canada; however they did not identify themselves publicly as Jews. Assimilation prevailed among these Jews, manifested in intermarriage and integration into aristocratic society, with nationality as the most important aspect of their identity.

By the end of the 19th century, Jews from Russia and Galicia arrived in Mexico, and they were associated by the European Jewish press with colonization projects. In 1891, when the Baron Maurice de Hirsch Fund was established in New York, and the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA) in London, several plans for the establishment of extensive Jewish farming settlements in Mexico were proposed, much like the kibbutzim the philanthropists were developing in Israel. However, this was not accomplished due to the negative reports that were given by the experts who were sent to evaluate this possibility. They thought that the potential settlers would not be able to compete with the cheap local labor work. In 1899, when the first immigrants from Syria reached Mexico, the above-mentioned Francisco Rivas Puigcerver started with his weekly journal El Sábado Secreto (later called La Luz del Sábado – “Shabbat Light”), dedicated to Sephardi history and language.

Immigration and Community Organization (1900–50)

The second wave of Jewish immigration peaked between 1911 and 1913 as a result of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. The deterioration in the quality of life of the Jews in the Turkish-Ottoman Empire, caused by political instability and the frequent wars with which they had to contend on their borders, forced the different Jewish communities to look for more appropriate geographical and economic arenas. The Empire’s breakup ended an era of relative tolerance, and the Ladino speaking Sephardic Jews began fleeing from their homes in present-day Turkey, while others left the Balkans, Syria and Lebanon (Arab speakers). The dark complexion of the Sephardic Jews, as well Ladino, their language with Spanish roots, eased their integration into Mexican society. Sephardic Jews were mainly street peddlers whose stands and carts, over several generations, often developed into shops and businesses.

Jews coming from Damascus and Aleppo maintained daily prayers and rituals inside private homes, owing to the fact that families had known each other previously and kinship was the basis for their strong union. Parallel to the informal gathering among the Syrian Jews, scattered Ashkenazim living in Mexico tried to organize a community. In 1904, a group called “El Comité” (The Committee) organized the Rosh Hashanah services on the premises of a Masonic Lodge. After this event, there were several attempts at community organization before the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, which was interested in establishing a Jewish community in Mexico to avoid illegal immigration to the United States, sent Rabbi Martin Zielonka to organize a congregation in Mexico in 1908. “The Committee” was then summoned and with the 20 attendees the “Sociedad de Beneficencia Monte Sinai” was established. However, the activities of this group were not fruitful, because many of them left the country with the outburst of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Today, the Sociedad membership is composed of approximately 2,300 families, many descendents of Jews that came from Damascus or Lebanon.

In 1912, the Alianza Monte Sinai – AMS re-constituted itself under Isaac Capon’s initiative. Born in Turkey, he was aware of the need to have a Jewish cemetery, since upon the death of his mother she had to be buried in a Catholic graveyard. All of the Jewish residents in Mexico, including the Syrians, participated in the initiative, and thanks to the good relationship between one of its members, Jacobo Granat, with the president at that moment, Francisco I. Madero, the AMS received permission from the authorities for the acquisition of the first Jewish cemetery. In 1918, AMS bought a house on Jesus Maria Street in the center of Mexico City where they decided to build a synagogue. The day when President Venustiano Carranza gave his authorization signature became a memorable one, because it was the first time the existence of a Jewish community was recognized by law. AMS kept itself united with ups and downs for a decade, during which religious services and financial and social assistance were given to the new immigrants, including Hebrew classes, kosher meat, a mikveh, and the services of a mohel.

Between 1913 and 1917, the revolutionary conflict caused a decrease in the Jewish population. The victorious Carranza’s regime, however, adopted liberal policies guided by the secular principle of religious freedom and, within this context, the formal recognition of the Jewish community, as well as other religions, meant the reconfirmation of modern ideology.

With the establishment of immigration quotas in the United States in 1921, which became stricter in 1924, many Jews decided to stay in Mexico.

The third, and final, wave of Jewish immigration came from Russia after the first World War. With an already established Jewish community, Mexico received Sephardim as well as Ashkenazim fleeing from Eastern Europe. Their number in 1921 was estimated at around 12,000 persons, about 0.1% in a country of 12 million inhabitants. Many of these Jews used Mexico only as a stopover on their way to the United States; however, a more restrictive 1924 American immigration policy stopped the flow of European Jews and those who reached Mexico had no choice but to begin new lives there. The Zionist Federation united various Zionist groups within Mexico’s Jewish community at this time. The first Ashkenazi organization, Niddehei Israel, was established in 1922 as a Chevra Kaddisha to help bury the dead, and subsequently developed into a Kehilla, or full-scale community, Consejo Comunitario Ashkenazi. Today, this Orthodox community has approximately 2,500 families.

The third wave also caused a rift between Mexico’s Ashekenazi and Sephardi Jews. As the Ashkenazi population grew in the early 20th century, it used more Yiddish, alienating the Ladino speaking Sephardic Jews. In 1925, the Sephardi founded their own Zionist organization, B’nai Kedem, and founded their own cultural organizations. The rift between Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews in Mexico is still an issue today.

The first Jewish immigrants from Europe arrived in Mexico in 1917 through the United States. They were young men who spoke Russian and Yiddish, who had evaded their military service and sustained political ideologies such as Zionism, Jewish Nationalism, and Socialism. They founded the first Jewish cultural organization in Mexico: the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), working as a club dedicated to the promotion of culture, sports, and society. This model was followed by some Jewish communities in the province, and during the 1950s also by the “Centro Deportivo Israelita” (CDI; Jewish Sport Center). In the 1920s, the YMHA, with its headquarters at Tacuba street no. 15, in the center of the city, became a place for social gatherings and for economic assistance to the new Ashkenazi immigrants.

Prayer in the synagogue and religious services for the Jewish residents in Mexico City started in 1922. At that time over half of the Jewish population came from Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and the Balkans. Nevertheless, Jews from Eastern Europe started to arrive by the thousands from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Austria, Germany, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, encouraged by the effects of World War I, the Russian revolution, and the economic depression in the area. In the 1920s alone approximately 9,000 Ashkenazim and 6,000 Sephardim increased the Jewish population to 21,000 persons.

An organizational readjustment occurred in this decade, characterized by the diversity in cultural patterns brought by the immigrants from their respective countries of origin. The differences in languages, in religious rituals, and in daily habits were obvious, especially among those who came from Europe and the Middle East. The Ashkenazi separation from the AMS was completed in 1922 when they decided to hold their religious services by themselves and to create their own organizations. The religious, ideological, and cultural plurality expressed in the welfare organizations, periodic publications, and artistic and cultural expressions show the dynamism of a community in the process of formation. In 1922, Nidhei Israel was created in order to take care of the religious needs (such as prayer, talmud torah, kashrut, ḥevrah kaddisha, and others). This institution became the Kehilá nucleus that was established with official recognition in 1957.

After some attempts begun in 1923, the Zionist Federation was established in 1925, with the different ideological trends of the Zionist Ashkenazi Jews. In the 1920s and the 1930s there were also active Bundist and Communist organizations. The Sephardim formed their own Zionist organization, Bnei Kedem, in 1925, because they did not feel comfortable in meetings where the predominant language was mostly Yiddish. In 1924, the Yiddishe Shul – Colegio Israelita de Mexico was founded, the first of a wide network of Jewish day schools still in operation.

In 1924, Jews from Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans – Ladino speakers – decided to separate from the AMS and establish their own community and welfare association “La Fraternidad” in order to help their fellow countrymen with economic, medical, and social aspects. In 1940 the “Union Sefaradí” was founded, with the fusion of “La Fraternidad,” the women’s mutual aid society “Buena Voluntad,” and the youth organization “Unión y Progreso.” Since then, this community has had a day school (founded in 1943), two synagogues, and a cemetery as well as a formal administrative structure. This community now has approximately 1,100 families.

The AMS was left actually in the hands of the Syrian Jews. Those who came from Aleppo (halebies), however, did not actively take part, because they had their own places of prayer and their own talmud torah, so that their economic participation was very limited. They even built their own synagogue, “Rodfe Sedek,” in 1931, and in fact were separated from the AMS. Problems arose when they wanted to make use of the cemetery and they were required to update the payment of their membership fees. The halebies founded their own communal and administrative institutions and bought their own grounds for a cemetery. In 1938, Sedaká uMarpé was founded, a charity society that grouped together the diverse institutions of men, women, and youth, as well as the observant groups that were in charge of the religious services, assistance, and social activities. On the other hand, the AMS, managed by the Dama-scenes since the second half of the 1920s, changed its statutes in 1935 and became an exclusive organization for this sector. By the end of the 1930s, the limits of the community structures were defined, so that community affairs administration would be taken care of by institutions organized according to their origin, and the original culture would be recreated within them, preserving the identity of the first immigrants.

Economy And Social Stratification

Since their arrival, Jewish immigrants dedicated themselves to commerce, mainly as peddlers. Before 1940 the Mexican population was basically rural, so that salesmen had to carry the goods to the smaller towns and not only to the urban centers. For this reason there were Jews who preferred to stay in the provinces and prospered as itinerant salesmen or with fixed or semi-fixed shops in the markets, even though most of them lived in the capital. Along with other foreign merchants, they introduced the credit system sales, which made it easier for their customers to enhance their lifestyle and acquire goods which otherwise would have been impossible to get. They sold shoes, socks, ties, fabrics, thread, stockings, ribbons, and some other consumer goods necessary for domestic use. In the second half of the 1920s, the B’nai B’rith contributed economically, together with the Ashkenazi associations, to incorporate immigrants; it gave them credit to start as merchants, taught them Spanish, and organized their social life.

Justo Sierra Synagogue, Mexico City |

In the 1930s, and as a result of the unemployment caused by the economic effects of the Great Depression of 1929, antisemitic and xenophobic movements promoted attacks against the vendors at “La Lagunilla” market. Antisemitism forced the small Jewish merchants to install their own commercial spaces as well as to establish small manufacturing workshops in order to protect themselves from the attacks of ultra-right nationalist groups, in the long run resulting in their economical ascendance. During this process the Banco Mercantil, founded by Jews in 1929 on the basis of a loan fund, financed the acquisition of machinery for the textile industry and industrial input assets. In 1931 the Cámara Israelita de Industria y Comercio (Jewish Industry and Commerce Chamber) was created in order to coordinate the economic efforts of the Jews and to serve as a representative organ of the Jews vis-à-vis the Mexican authorities and the society at large.

The 1940s in Mexico were outstanding, because it was the starting point for a sustained economic growth that lasted for over 30 years. World War II promoted the export of food and basic goods into the United States as well as the strengthening of the Mexican internal market. The imports substitution program, launched by the government, stimulated the creation of industries in a protected economic environment. The Jews saw in this project the opportunity for improvement, so they established manufacturing factories, especially in the textile field. Their economic status improved and the occupational areas that participated were also diversified. A survey performed in 1950, among the Ashkenazi sector, found 52 occupations in different fields, especially commerce and industry and also professions such as medicine, engineering, and the sciences.

Immigration and Anti-Semitism

When they first arrived, many Jews, embittered by the anti-Semitism in Europe, were distrustful of Mexico, a nation 97 percent Catholic. But Mexico, with a few exceptions, has treated its Jews exceptionally well, and is considered a haven for them.

Mexican migratory policy turned from an open attitude to a restrictive one based on racial selection. Before the Mexican revolution there were practically no regulatory laws. In the 1920s, presidents Obregón and then Calles, in their national reconstruction goal, invited the Jews to move to Mexico with the purpose of promoting the economic development of the country. However, in 1927, the Mexican Congress approved new legislation on immigration according to racial criteria, considering the assimilation capacity of the immigrants into the mestizo (mixture of Indian and Spanish) races of the country as well as the country’s economic absorption capacity and the immigrants’ contribution toward its productive development. In 1929, the entrance of workers was prohibited.

One of the few anti-Semitic incidents occurred in 1930 when a two year economic slump in the Languilla caused storekeepers to begin an anti-Semitic movement. The incident ended when the U.S. Department of State intervened, convincing the Mexican government to end the movement.

The increase of anti-Semitism, expressed in the attacks of fascist groups, such as the “Camisas Doradas” (Golden Shirts), reinforced the unity of the Jewish community to resist the situation. During the 1930’s, the Jewish community battled anti-Semitism by forming the Federacion de Sociedades Judias, as well as the Comité Central Israelita de México (Central Jewish Committee of Mexico), which is an umbrella institution of all the existing Jewish organizations. International organizations, such as the Joint Distribution Committee and the World Jewish Congress, also became active in Mexico.

The 1936 Population Law established differential quotas according to the national interest (racial assimilation and economic potential), elaborating tables with restrictions to the admission of certain foreign groups. The following year, entry to Mexico was strictly limited from nations heavily populated by Jews such as Poland and Rumania to 100 per year. German and Austrian Jews, who fled the racial laws of the Nazi government, also had difficulties in entering the country, despite the intensive efforts made by the Jews on the local and international levels. For the Polish and Romanians only ten visas per year were available, clearly insufficient facing the scope of the European problem. Throughout the period of Nazi persecution (1933–45), Mexico accepted only 1,850 Jews.

Anti-Semitism peaked during World War II, but was mitigated by Mexico’s entrance into the war with the Allies in 1942. In 1944, the Anti-Defamation League was created within the Comité Central, becoming better known by the name of its journal Tribuna Israelita, with the objective of preventing antisemitism.

Since the Holocaust, there have been few cases of anti-Semitism in Mexico. Mexico’s post-war economic prosperity translated into religious tolerance for the Jews, who enjoy the same rights as other Mexican citizens. Jews hold, and have held, high positions in Mexican government as well as in the business sector, where there are well-respected Jewish artists, journalists and businessmen. Most Mexican Jews are considered middle to upper-middle class.

The cases of anti-Semitism that do exist stem from the Israel-Arab conflict, as well as Mexico’s right to free speech, which has attracted neo-Nazis and allows them to express their views. Even so, anti-Semitism is not a serious threat to Mexican Jewry. The most serious issues facing the Jewish population are intermarriage and defection to America. In June 2003, President Vicente Fox passed a law that forbids discrimination, including anti-Semitism, putting into the law what has been practiced for years.

Comité Central has a special body named Tribuna Israelita, which is in charge of relations with mass media and the fight against anti-Semitism. Also as part of the Comite Central there is the Order and Security Committee, which is responsible of Bitajon and the Comisión de Acción Social, which is in charge of helping those members of the community that are assaulted, kidnapped, and threatened.

Zionism

The events that marked world Jewish history in the middle of the 20th century, the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel, were present in the life of the Jewish Mexican community and its leaders. Zionism was the flag identifying Mexican Jews vis-à-vis the national society. The Jewish efforts to achieve the legitimation of the national Jewish aspirations and the obtaining of a favorable vote from Mexico on the partition of Palestine in the United Nations in November 1947, was the main challenge for the Zionist sector. The coordination, unification, and efforts were manifested in the creation of the Zionist Emergency Committee and the Emergency pro-Palestine Jewish Committee, representative organizations of the Jewish community before the Mexican society. The legitimate demands that accompanied the Zionist ideals as a national liberation movement, gave a positive image of Judaism, compensating for the impact of previous anti-Jewish expressions and demonstrations, despite the abstention of Mexico in the United Nations in 1947.

The creation of the State of Israel in 1948 had concrete effects within the internal dynamic of the Ashkenazi sector; the organized unification of the Zionist parties and groups became a reality in 1950. The Zionist Federation of Mexico became the framework in which the different sectors coordinated their efforts thanks to the links established with Israel. The new state replaced the Zionist party organizations with government institutions, a process that the Zionists in Mexico also followed as they developed community institutions. Since then, Israel became the central issue for the secular Jewish solidarity and identification. Within the Sephardi community, the Zionist youth organizations were very active. In the case of Sedaká uMarpé and AMS, Zionism introduced a new element of identity and Jewish pride, and gave meaning to their work on behalf of the State of Israel.

Consolidation of the Jewish Community in Mexico

During the first half of the 1950s the Club Deportivo Israelita (CDI) was created, becoming the largest organization of Mexican Jewry, with the affiliation of Jews from all the community’s sectors, becoming one of its most inclusive institutions. The objective of the CDI was to stimulate physical and cultural activities allowing the association of children, youngsters, and adults. Around 15,000 Jewish families are members of the CDI, including some non-affiliated.

The two main communities that consolidated outside Mexico City and its metropolitan area since the 1930s are Monterrey and Guadalajara, consisting of approximately 150 families each. Having created institutions that include synagogues, schools, recreational facilities, and their own cemetery, both maintain religious institutions and organizations for women and men, where Ashkenazim and Sephardim gather in the same community space. In Tijuana there is also a community of 70 families that since 1943 had been closely linked to the U.S. community of San Diego. Some Jewish families also live in Veracruz, Puebla, and Cuernavaca, however, with no representative institutions. In the 1990s, in Cancún, community life has been promoted among the 70 families that moved to that city.

In the 1950s and the 1960s, the Jewish institutions were consolidated. The fast economic ascent of the Jewish families, made possible the change of residential neighborhoods in Mexico City: from the downtown area and “Colonia Roma” to “Condesa” and “Polanco”; for this reason some new community facilities were built, such as large and elegant synagogues, new school buildings, new community centers, and places for the youth movements. These were the years in which the religious attachment diminished because the Jewish core identity remained linked to Zionism, coinciding with the secularization process with which Mexican society was experimenting along with its fast growing urban modernization. It is quite significant that during this period there emerged the only two Conservative synagogues that exist in Mexico City: Bet Israel created in 1953 by American Jews (with membership of approximately 230 families today), and Bet El founded in 1963 by Ashkenazi Jews (with membership of approximately 230 families today), who were not able to find in the religious legacy of their parents a meaningful Judaism, and decided to be separated from the Kehilá to practice more modern religious forms that were closer to their reality. However, in the Ashkenazi sector as well as among the Sephardim, there remained vigorous nuclei of religious Orthodox families who continued the rites and practices preserving the different modalities according to the original tradition of the immigrants.

Social Integration and Identity

The socioeconomic improvement placed the Jews in the upper levels of the Mexican society and their cultural practices resembled those of the elite. Many sent their children to American schools to learn English, intermingled with Mexican entrepreneurs to do business, and made frequent trips to the United States. The Jews learned how to adapt themselves into the Mexican political system; they registered their institutions according to the national schemes, e.g., the welfare societies were registered in the Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia (Health and Welfare Ministry). However, an asymmetric relationship with the government prevailed, since it recognized the Jews as citizens, but did not consider them as a distinct group, although in fact it did treat them as such. This situation was reproduced in the next generations, which were perceived as foreign as their parents had been, despite the cultural synthesis with which they were experimenting, and they remained suspect of maintaining dual loyalty, to the Jewish people and to the Mexican nation, which in a way took away their credit as legitimate Mexicans. This constant questioning led the Jewish community to live as an enclave, at the margins of the political and social life of the country. The isolation of the Jews was the result of an internal attitude of wanting to preserve the social community living space, and an external one due to the rejection of the general society to admit differences.

By the 1970s the anti-Zionist government policy was expressed in the international arena, when in 1975 the president of Mexico, Luis Echeverría, proposed, before the United Nations General Assembly, that Zionism was a form of racism. The Mexican-Jewish community had very little influence on trying to alter this proposal, which was approved by the majority with the support of the Arab nations and their allies of the Third World. Diplomatic relations between Mexico and Israel became tense and the tourism boycott of the American Jews against Mexico had an influence on the change of the Mexican position towards Zionism. This change came in 1992 when another Mexican president, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, proposed at the United Nations General Assembly to abrogate this resolution, a proposal that was approved.

Nidje Israel Ashkenazi Beth HaKnesset, |

The third Jewish generation in Mexico lived in a hard national economic context, marked by a crisis that returns every six year, which means they have to confront a constant challenge to the maintenance of the social status acquired by their parents. In the 1980s and 1990s, Mexico and the world were facing changes in the economic model toward an open economy. Not all the Jews adapted themselves successfully. Just like other small- and middle-sized merchants and industrialists in the country, they suffered from the consequences of the international competition for which they were not prepared. The opening of the Mexican markets provoked a strong readjustment in the textile industry and a great recession in the construction field, areas in which a large number of Jewish entrepreneurs were involved. The collapse of enterprises and the consequent loss of jobs among the Jews led to more employees and professionals and fewer company owners. Facing this situation, all the community organizations started a program known as “Fundación Activa” which gives training and tutorial assistance for self-employment and for the creation of micro-enterprises that do not require large investments. This and other assistance programs contributed to the stability and cohesion of the Mexican Jewish community and helped to maintain its institutional diversity and its demographic and socioeconomic level, preventing poverty and/or migration.

From the 1990s Mexican Jewry experienced an increase of religiosity in some of the community’s sectors, that may be associated with this economic, political, and cultural trend in the global and national environment. The number of synagogues and especially of midrashim and kolelim (religious adults’ study centers for bachelors and married men respectively) rose, in particular in the most Orthodox sector, the Maguén David Community, formerly the Aleppan Sedaká uMarpé, which had been founded in 1937 by Jews from Aleppo. This trend is a new development in the religious life in Mexico, since it is linked to the ultra-Orthodox movements from Israel, in which there is a kind of synthesis of the religious tradition of the communities of Middle Eastern origin with the Ashkenazi tradition.

A significant change in the relations between the Jewish community and the Mexican State was felt after the creation of the “Ley de Asociaciones Religiosas y Culto Publico” (Religious Associations and Public Cult Law) in 1992. Until the 1990s, the Jewish minority had adapted to the limited space given by the State, registering itself as civil associations. Since the 1940s, the relations between State and Church were based on the agreement, according to which the government did not interfere in the affairs of the Church in exchange for the recognition of the Church in the sociopolitical hegemony of the State. This relation was also applied to the Jewish case. This was illustrated in the increase in Jewish schools during the 1940s, which besides the official program taught Jewish history, Bible, and tradition which could be interpreted as religion. The State tolerated this kind of expression even though it was forbidden by law.

The reforms of 1992 in the Constitution, related to the legal recognition of the religious institutions and their public activities, attempted to normalize the common practices. This kind of legality recognizes the legitimacy of group consolidation through the religious identification. The religious associations became another channel of collective expression. The religious and ideological diversity in the society increased in correlation with a greater democratization of political and cultural life. Gradually the participation of the Jews in these areas is becoming wider and less questioned everyday, and the presence of Jews in senior official posts is becoming more frequent.

As we have seen, the Jewish community in Mexico is highly organized within well-defined communities according to the origin of the first immigrants; each of these groups is represented at the Comité Central de la Comunidad Judía de México (Central Committee of the Jewish Community of Mexico) which is in charge of maintaining the relations with government authorities as well as with the social and cultural organizations in the country. Tribuna Israelita is the executive arm of the Comité Central in anti-defamation duties, preventing and denouncing antisemitism and violence against Jews.

Aside from the services provided by the Communities to their members there are several programs that are handled in an inter-communal basis:

- Umbral: provides preventive work against addiction (alcohol, smoking, drugs, etc.) It works very closely with the schools and youth organizations.

- Kadima: works with handicapped people and helps them integrate into general society. They teach the Jewish community how to interact with these people.

- Fundacion Activa: helps people who are unemployed, providing services to help them find a new job. They also provide therapy for those who are depressed, and have a small business center to help people create their own company.

- Menorah and “Erej” from Na’amat: These two organizations work to prevent domestic violence, and provide therapy victims and their families.

- Eishel: is a retirement home in the city of Cuernavaca, some 70 kilometers from Mexico City, providing everything the elderly need. There is almost one nurse or a social worker per person. They provide kosher food and special diets for each resident. Those who can afford to pay a monthly fee do so, while those who cannot do not have to pay.

- Beyajad, Atid and Kol Hanisayon: These three institutions provide activities for the elderly that live in their homes or with their families.

- OSE: Provides medical facilities for the needy people in the Jewish Community. It has a clinic with beds for non-surgical cases and post-operation recuperation. It also has a pharmacy that provides medicines at great discounts and provides medical attention for free or very low cost.

Demography

Today, Mexico boasts a strong, active Jewish community approximated at 40,000 - the fourteenth largest Jewish community in the world. The vast majority of Mexico’s Jews live in the capital of Mexico City, where there are 23 synagogues, several Kosher restaurants and at least 12 Jewish schools. Within all the communities, there are around 30 permanent synagogues and about 20 additional places of worship during High Holidays.

Small Jewish communities can also be found in Guadalajara , Monterrey, Tijuana, Cancun and San Miguel. Throught all of Mexico, 95 percent of Jewish families belong to a synagogue. Eighty to ninety percent of Jewish children in Mexico City attend a Jewish school. Only about 1 out of every 10 Mexican Jews intermarries. This is way below the fifty precent rate of the United States and one of the lowest rates in Latin America. The world’s largest city also contains the Tuvia Maizel Museum, dedicated to the history of Mexican Jewry and to the Holocaust.

According to a socio-demographic study of the Jewish community in Mexico, performed by request of the Comité Central in 2000, the number of families and their percentage per sector is as follows: Maguén David: 2,630 families (25.8%), Monte Sinaí: 2,350 (23.0%), Kehilá Ashkenazí: 1,870 (18.4%), Sephardi Community: 1,150 (11.3%), Bet El: 1,080 families (10.6%), CDI: 340 families not affiliated to other sectors (3.3%); Bet Israel: 260 (2.6%), Guadalajara: 250 (2.5%), and Monterrey: 250 families (2.5%), which gives us a total of 10,180 families.

Demographic tendencies show a larger growth in the non-Ashkenazi sectors that became the majority of the Jewish population in Mexico. Almost all the Jews marry Jewish spouses. According to the socio-demographic study of the Jewish population performed by DellaPergola and Lerner in 1991, between 5% to 10% of the marriages are exogamic. Marriages within the community of origin are the most frequent, even though every day there are more inter-communal marriages. The main Jewish residential neighborhoods are located in the northeast of the Metropolitan area: 28.6% live in Las Lomas, 21.8% in Tecamachalco, 21.6% in Polanco, 16% in La Herradura, and the rest in Hipodromo-Condesa, Narvarte, Satélite, and other neighborhoods.

The occupational structure is as follows, according to the data of 1991: 53% of the economically active people are in the managerial sector as owners of businesses and directors, 27% professionals, 11% office employees, 5% merchants, and 4% handcraft workers. The analysis of this data by age groups confirms the well-known upward economic mobility of the Jewish population as well as the tendency toward a larger professional sector in the new generations. The total of the work force is divided into three groups according to the branch of production: industry (35%), commerce (29%), and services (28%) and two groups with minor incidence, which are construction (3.5%) and personal services (4%). The family and social networks have an important influence in the integration pattern of the working force in economic activity and represents 75% of the work location grounds.

Jewish Education and Jewish Culture

In many cases the community institutions organized schools of Jewish studies for the children of their members. They established talmudei torah and Kutabim (complementary traditional schools), and also day schools in which general studies were imparted together with subjects of Jewish culture. At the beginning, the Jewish studies were learned in Yiddish, Arabic, or Spanish, together with rudimentary knowledge of Hebrew. The first day school was the Yiddishe Shul – Colegio Israelita de Mexico, established in 1924 by Meir Berger. During the first decade Jewish studies were taught in Yiddish. In the 1930s a few attempts were made to teach in Hebrew but they failed. Since then the school has defended Yiddish as a fundamental cultural current of Judaism. In the 1940s many new schools were established, according to the ideology of the founders and the parents, and also according to the community of origin of the families.

Two schools were established in 1942: the Hebraist school Tarbut by Avner Aliphaz and Yeshaiahu Austridan, and the Ashkenazi religious school Yavneh. They were followed by the Hebraist schools of the Sephardi community (1943) and that of the AMS (1944). All these schools adhered to the Zionist movement or sympathized with it, and after 1948 they were among the most important vehicles for the linking of the communal identity with Israel. In 1946 a Teacher’s Seminary was established in the Yiddishe Shul by its new principal, Avraham Golomb. In 1947, the day school Sedaká uMarpé of the Aleppan community was founded and functioned until 1951 without a curriculum in Jewish studies. In 1950 Avraham Golomb left his former school and established a new Ashkenazi school – the Naye Yiddishe Shul I.L. Peretz – Nuevo Colegio Israelita with a Yiddishist trend and inclination towards the Bund. The Sephardi School, the Monte Sinaí School, and the Teacher’s Seminary adhered to the Zionists and adopted the educational politics sent from Israel to the Diaspora. The schools were connected to the Vaad haHinuch (educational council), that was linked with the Jewish Agency and the State of Israel. The Jewish Agency assigned to the schools in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s Israeli sheliḥim – teachers and principals – to teach Hebrew, Yiddish, and Jewish culture, and to bring the schools closer to the Jewish state. Since then the schools have employed Israeli educators on their own.

Today, the Jewish education network has more than a dozen schools in Mexico City. It is estimated that more than 80% of the Jewish children attend Jewish day schools from kindergarten to secondary school. Some of these day schools have Jewish religious studies as in a yeshivah. The Jewish curricula of these day schools include Hebrew language and literature, Jewish history, Bible, tradition, and in some of them Yiddish language and literature. There is a Jewish pedagogic college – Universidad Hebraica – which prepares new professionals for Jewish education. The Universidad Iberoamericana (a private university) offers a study program on Jewish Culture linked to disciplinary studies in the Humanities. The educational level in the Jewish community has increased considerably: in 1991, 57% of the Jews in the 30 to 64 age group were university graduates, as compared with 8.5% for those older than 65. Most frequently, people with graduate and postgraduate studies are found among the members of the Bet El and Bet Israel congregations (49%) and in a slightly lower proportion in the Kehilá Ashkenazí (38%). Conversely, the presence of people with university studies is lower in the Maguén David and Monte Sinaí communities (18 and 10% respectively). However these differences tend to diminish in the younger generations. In addition to education, community life dynamics are expressed in a variety of social and cultural activities. Besides the activities performed by each of the community sectors, there are also inter-communal organizations, such as the women’s associations WIZO, Na’amat, and the Mexican Federation of Jewish Women or the Mexican “Friend Associations” of the Israeli universities.

There are around 16 youth movements with approximately 2,000 members, most of them identified with the State of Israel. Each year several hundred Mexican Jewish youngsters visit Israel in groups organized by the schools. The Federación Mexicana de Universitarios Judíos (FEMUJ) and the Federación de Universitarios Sionistas de Latinoamérica (FUSELA) have a significant presence in the community. Since 1948, nearly 4,000 Mexican Jews have made aliyah.

The Jewish press is diverse but mainly dedicated to inner community matters. The news or ideological publications typical of the 1940s and the 1950s, mainly in Yiddish, no longer exist. Each community sector has its own bulletins and periodic magazines. There are some independent organs such as Foro magazine distributed through subscriptions or Kesher with free distribution in all the communities and the Centro Deportivo Israelita. The Jewish journalists and writers association meet and express themselves through the community press.

The Jewish museum named Tuvia Maize is dedicated to the history of the Jewish community in Mexico and to the Holocaust. At the Ashkenazi Kehilá there was established a Centro de Documentación e Investigación (Center for Documentation and Research); it preserves historical documents of the Jewish Community in Mexico, as well as books in several languages, that were part of private libraries of the first immigrants, and promotes the publication of documentary books and researches.

Another important cultural site is the Centro Deportivo Israelita (CDI), which besides having excellent sports facilities, has an art gallery, a theater, and a banquet hall. This is the location of the most important Annual Jewish Dance and Music Festival in Latin America.

In 2019, a Jewish Documentation Center opened in the Rodfe Sedek synagogue in Mexico City. The center contains a library of 16,000 books in multiple languages, 1,500 newspapers, photos documenting Jewish life in Mexico and other documents and artifacts.

In a historic July 2018 election, Mexico City elected a Jewish woman as their Mayor. Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo was not only the first Jewish individual to be elected Mayor of Mexico City, she was also the first woman to be elected to the position. Sheinbaum had previously served as Mexico’s Secretary for the Environment. Approximately 50,000 Jews call Mexico City home.

Religious Life

Templo Adat Israel Shul de Alamos |

In Mexico City, there are around 25 synagogues and an equal number of small places for prayer and study that belong to the most Orthodox sectors in the community. Two of the synagogues are Conservative, and all the others are Orthodox. The level of religious observance has increased by 4% from 6.7% Orthodox Jews, according to the results of the socio-demographic study of 1991, to 10.7% according to that of 2000. Most of the Mexican Jews consider themselves as traditionalists (76.8%) while the non-observant, secular, and atheist Jews comprise 12.5%, according to the data of 2000. When analyzing figures per community, Maguén David presents the lower index of traditionalists (66%) and an equal number of Orthodox (17%) and non-observants (17%), which shows a tendency toward polarization of the religious and the non-religious. In contrast, 86% of those affiliated to Bet El considered themselves traditionalist. The most popular ritual practice is the Passover seder celebrated by 93% of the population within the family. In second place is the Yom Kippur fast observed by 89%, and after that, Hanukkah festivities in which 71% perform the ritual of candle lighting, while the frequency of other religious practices is reduced to half or less. In relation to the regular observance of Shabbat, 12% rest, 49% eat kosher meat, and 19% separate their dishes.

Isla Mujeres

Isla Mujeres is an island paradise a 20-minute ferry ride from mainland Cancun, Mexico. The island is home to 15 Jewish families out of a a year-round population of 13,000, who enjoy food at local kosher cafes and participate in weekly services at the local Chabad house. The Jewish residents are comprised of the elder generation who came to the island in the 1960’s and 70’s, young Israelis who moved to the Island for a less complicated life, and young Rabbis who run the Chabad Isla Mujeres. The island is a popular destination for Israelis looking to relax following their conscripted military service.

Since most of the early Jewish immigrants were well-established middle-aged couples in the 1960’s and 70’s, not much attention was paid to establishing Jewish schools or other religious institutions. More recently, as the influx of young Jews to the island continued, a Jewish school was established that currently has 6 students. In 2012 the Chabad Isla Mujeres welcomed 70 guests to it’s first Passover Seder, including tourists, young Israelis fresh out of the army, and sponsors from Chabad Crown Heights who had given the Rabbis seed money and support to start the congregation. Within two years, the Chabad Isla Mujeres was hosting holiday dinners easily exceeding 500 people in attendance. The Chabad Isla Mujeres is supported by Chabad International and other organizations in the United States and Israel, as well as individual donations from their members.

Relations with Israel

Mexico abstained in the vote of November 29, 1947, on the partition of Palestine. On April 4, 1952, Mexico recognized the State of Israel, and shortly afterwards the two countries established diplomatic relations, opening embassies in both countries. At the beginning, Mexico adopted a policy of neutrality, abstaining from voting at the international forums where Middle East affairs were dealt with. However, since the Six-Day War in 1967, this position changed and Mexico frequently votes against Israel. The most delicate moment was the above-mentioned equation of Zionism with racism in the 1970s abrogated in the 1990s.

Commercial exchange between the two countries was very low until the end of the 1970s (with an annual average of under $2 million). In the 1980s, its scope started to increase, with an average of $25 million annually (14.8 exports from Israel and 11.3 imports). In the 1990s, bilateral relations improved: cultural agreements were signed, and there were visits from ministries and functionaries of both countries. Israel has provided technical and scientific counseling to certain areas of agriculture and industry in Mexico, and Israel also buys manufactured products, food, and Mexican oil. Nevertheless, the volume of trade remained close to the same level. In 2000, a Free Trade Agreement was signed between both countries when President Ernesto Zedillo visited Israel, and ever since, economic exchange has increased. Exports from Israel jumped to $212 million and imports grew to 17 million. This unbalanced relation between exports and imports has continued since then. The total volume of commerce in 2001 was over $169 million (155.6 exports and 13.5 imports), in 2002 close to $212 million (191.6 and 20.2), in 2003 over $246 million (228.7 and 17.6), and in 2004 more than $362 million (340.5 and 22.1).

Mexico’s Ambassador to UNESCO, Andre Roemer, was fired on October 17, 2016, for protesting his country’s decision to vote in favor of a UNESCO resolution denying Jewish connection to the Temple Mount and various other holy sites. Roemer, a Jew, was fired from his position for “not having informed diligently and with meticulousness of the context in which the voting process occurred, for reporting to representatives of countries other than Mexico about the sense of his vote, and for making public documents and official correspondence subject to secrecy,” according to an official statement from the Mexican government. Roemer left the room during UNESCO’s vote on the resolution in the first week of October. Despite the Mexican governments obvious opposition to Roemer’s actions, following his removal from his position the Mexican government officially changed their vote on the resolution from in favor to abstain, citing the “undeniable link of the Jewish people to cultural heritage located in East Jerusalem.” Roemer was honored by the American Sephardic Federation, and was the recipient of the International Sephardic Leadership Award at the organization’s conference in May 2017.

Ironically, this was also around the time Mexico started to change its votes at the UN from noes to abstentions. The timing also coincided with the election of Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto. He visited Israel in 2016, the first official visit by a Mexican president since 2000.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited Mexico during a September 2017 trip to Latin America, the first time a sitting Israeli Prime Minister has visited the Central-American country. While in Mexico the Prime Minister participated in events organized by the local Jewish community and signed bilateral space, aviation, communications and development agreements. The two nations agreed to begin negotiations to update their free trade agreement, which was signed in 2000. Israeli officials expressed interest in assisting the U.S. and Mexico develop Latin America with telecommunications and technology projects, and President Nieto welcomed the offer.

In May 2018, Israeli water desalination company Fluence announced a plan with local partners to build a $48 million, 5.8 million gallon/day seawater desalination plant for the town of San Quintin, Mexico and the surrounding areas. The plant will serve more than 100,000 residents in the Baja California region of Mexico, which had been under an officially declared drought since 2014. It is estimated that the desalination plant will be operational by 2021.

ADD. BIBLIOGRAPHY:

P. Bibelnik, “Olamam ha-Dati shel ha-Mityaḥadim be-Mexico ba-Me’ah ha-Sheva-Esreh,” in: Pe’amim, 76 (1998), 69–102; idem, “Mishpetei ha-Inkviziẓyah neged ha-Mityaḥadim be-Mexico (1642–1659),” in: D. Gutwein and M. Mautner (ed.), Law and History (1999), 127–45 (Heb.); J. Bokser-Liwerant (ed.), Imágenesde un Encuentro. La presencia judía en México durante la primera mitad del siglo XX (1992); I. Dabbah, Esperanza y realidad. Raíces de la Comunidad Judía de Alepo en México (1982); S. DellaPergola and S. Lerner, La población judía en México: perfil demográfico, social y cultural (1995); D. Gleiser Salzman, México frente a la inmigración de refugiados judíos, 1934–1940 (2000); A. Gojman Goldberg, Los Conversos en la Nueva España (1984); A. Gojman de Backal, “Los Conversos en el México Colonial,” in: Jornadas Culturales. La presencia judía en México (1987); idem, Generaciones Judías en México. La Kehilá Ashkenazí (1922–1992) (1993); idem, Camisas, escudos y desfiles militares. Los Dorados y el antisemitismo en México (1934–1940) (2000); N. Gurvich Peretzman, La memoria rescatada. La izquierda judía en México y la Liga Popular Israelita 1942–1946 (2004); C. Gutiérrez Zúñoga, La Comunidad Israelita de Guadalajara (1995); L. Hamui de Halabe (ed.), Los Judíos de Alepo en México (1989); L. Hamui de Halabe, Identidad Colectiva. Rasgos culturales de los inmigrantes judeoalepinos en México (1997); idem, Transformaciones en la religiosidad de los judíos en México (2004); C. Krause, Los judíos en México. Una historia con énfasis especial en el período 1857 a 1930 (1987); S. Liebman, Los judíos en México y América Central (Fe, llamas e Inquisición) (1971); A. Toro, La Familia Carvajal (1944); M. Unikel Fasja, Sinagogas de México (2003); E. Zadoff, “La disputa en torno al idioma nacional en los colegios judíos ashkenazíes de México a partir de la década de 1930,” in: Judaica.

Sources: Mexico City elects first Jewish mayor,

JTA, (July 2, 2018);

Fluence to build seawater desalination plant in Mexico,

Israel21c, (May 2, 2018);

Mexico accepts Israeli offer to help develop Central America,

Reuters, (September 14, 2017);

Latin American Allies,

Jerusalem Post, (September 10, 2017);

Mexican diplomat to be honored for challenging UNESCO anti-Israel vote,

Jerusalem Post, (April 30, 2017);

“Mexico fires Jewish ambassador who protested UNESCO vote, but will now abstain,” JTA, (October 18, 2016)

Louis Nayman. “We are the Jews of Isla Mujeres,” Tablet, (April 27, 2015);

Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2007 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

Jewish Communities of the World, Mexico;

Jews in Mexico, a Struggle for Survival ;

JTA Global New Service of the Jewish People;

"Mexico." The Jewish Travelers’ Resource Guide. Feldheim Publishers. 2001;

Alan Tigay, The Jewish Traveler. Jason Aronson, Inc. Northvale, NJ, 1994;

Alan Grabinsky, “New Jewish Documentation Center, Containing 100 Years of Jewish Life in Mexico City, Opens This Week,” Tablet, (January 7, 2019).

Photo Credit: Beach in Cancun, by Mardetanha.