The Written Word

Three manuscripts in the Hebraic Section permit us to

witness the extent of Karaite sectarianism in the fourteenth century; a visit to an Egyptian synagogue in

the nineteenth; and a glimpse at Jewish life in the Islamic Middle East in

the eighteenth.

The oldest dated Hebrew manuscript at the Library is a

thirteen-page Hilhot Shehita (Laws of Ritual Slaughtering) by the

Karaite scholar Israel Ma'arabi, written in 1397 by the scribe Joseph ben

Abraham ben Joseph. The Karaite sect, as noted, had its origins at the beginning of the eighth century and

rejected Talmudic-rabbinic tradition, so it is not surprising to find in

this manuscript that a Karaite shohet (ritual slaughterer) is

required to deny the Rabbanites' "Mishnah and Talmud."

Written in 1397 by Joseph ben Abraham ben Joseph, this

manuscript of the Karaite laws of Shehita (ritual slaughtering), by

Israel Ma'arabi, is the oldest manuscript in the Hebraic Section. It is

open to the beginning of Chapter Nine, which deals with the

blessings to be recited at the ritual slaughter of the fowl or animal,

Israel Ma'arabi, Hilhot Shehita. Scribe: Joseph ben Abraham ben

Joseph, n.p., 1397. Hebraic Section, Library

of Congress Photo).

|

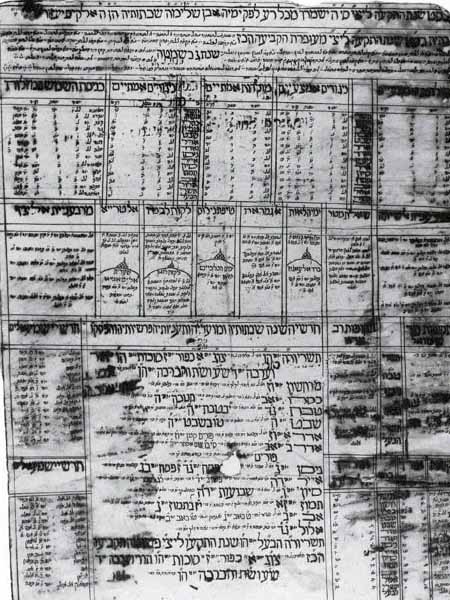

A manuscript wall calendar for the year 5575 (1815),

which apparently hung in an Egyptian synagogue, is of interest to students

of the Jewish calendar, the synagogue, and Egyptian Jewry Twenty-four by

eighteen inches in size, it contains the reckonings of Mar Samuel

and Rav Adda. The former, head of the Nehardea Academy in Babylon in

the second century, reckoned the year to consist of fifty-two weeks and one

and one-quarter days. Over the course of twenty-eight years he made the

adjustments necessary to bring the solar and lunar calendars into harmony.

A more exact calculation of the length of the year is attributed to a Rav Adda (probably, Rav Addah ben Ahavah), a third-century

Babylonian scholar. Both ancient calculations persist in this

nineteenth-century Jewish calendar, which also notes the "Islamic

months."

A wall calendar in manuscript, hung in an Egyptian

synagogue, to be available to all members of the community. It

contains all pertinent calendrical information for Jewish observance and

lists the Islamic months as well. Wall Calendar, Egypt, 1815. Hebraic

Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

The most interesting manuscript is a Hebrew translation

of the Koran, one of only three such extant Hebrew manuscripts, the others

being in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, and the British Library in London.

The Library of Congress Hebrew Koran is a manuscript of 259 leaves, without

a title page, and it contains no indication as to translator, scribe, or

place and date of composition.

One of the three recorded manuscripts of a Hebrew

translation of the Koran, written in Cochin in the middle of the eighteenth

century, it opens with: "The customs of Ishmaelites," i.e.,

Moslems: "The Moslems believe in God who is One; One Essence, One

Form, Creator of Heaven and Earth, He rewards those who do His will, and

punishes those who transgress His ordinances ... and Mohammed was His great

prophet, who was sent by God to teach mankind the way to eternal

life," Koran, Hebrew Translation [Cochin], 1757. Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

In a tour de force of bibliographical sleuthing, Myron

M. Weinstein, former Head of the Hebraic Section, using both painstaking

scholarship and creative imagination, offers the missing date and even a

nineteenth-century provenance. In his "A Hebrew Qur'an

Manuscript" in Jews in India, edited by Thomas A. Timberg,

Weinstein, in elegant narrative style, leads the reader along a thoroughly

documented road, at whose end we are convinced that this Hebrew version is

a translation from a Dutch copy which is itself a translation from the

French translation of the original Arabic. Weinstein also persuades us that

the translator is Leopold Immanuel Jacob van Dort, a Jewish convert to

Christianity who was professor of theology in Colombo, Ceylon, and that the

scribe was David Cohen, a native of Berlin then residing in Cochin, a city

on the southwest coast of India. Weinstein is equally persuasive about the

manuscript being written in Cochin in the 1750s or 1760s, probably in 1757,

when van Dort was visiting that city, and that is the volume the missionary

Joseph Wolff saw in Meshed, Persia, in 183 1, when he encountered a group

of Jewish Sufis. Wolff writes:

I met here in the house of Mullah Meshiakh with an

Hebrew translation of the Koran, with the following title: "The Law of

the Ishmaelites, called the Koran, translated from the Arabic into French

by Durier, and from the French into Dutch by Glosenmachor, and 1, Immanuel

Jacob Medart, have now translated it into the holy language, written here

at Kogen, by David, the son of Isaac Cohen of Berlin."

From Cochin to Meshed to Washington, and who knows where

in-between, a hegira from the ends of the earth indeed!

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress,

1991).

|