The Work of Maimonides: The Turim

In the fifteenth century, the Mishneh Torah was already viewed more as the textbook of Jewish law than a practical code. That function was being assumed by the Arba-ah Turim of Jacob ben Asher (1270(?)-1340), who in 1303 accompanied his father from their native Germany to Toledo, Spain. He felt that reasoning had become faulty, controversy had increased, opinions had multiplied, so that there was no halakic ruling which was free from differences of opinion, hence the need for a new code. Though he revered Maimonides and accepted his halakic authority, he found three difficulties with his classic code: it was too long, containing laws no longer applicable after the destruction of the Temple and outside of the Holy Land; it was overly theological; and it reflected the Sefardi tradition alone to the neglect of the Ashkenazi. Ben Asher based his code on Maimonides's, but its structure was existential, beginning with the laws one is to observe upon waking in the morning and presenting only laws applicable to life in the Diaspora.

The Mishneh Torah begins with:

The basic principle of all basic principles and the pillar of all knowledge is to realize that there is a First Being who brought every existing being into being. All existing things, whether celestial, terrestrial, or belonging to an intermediate class, exist only through this true existence.

The Arba-ah Turim opens with

Judah ben Tema says: be as courageous as a panther, light as an eagle, swift as a deer, strong as a lion to do the will of your Heavenly Father.

The laws in the Turim reflect the Sefardi tradition, as recorded by Maimonides, and the Ashkenazi usage, as presented by Jacob's father, Rabbi Asher. Both communities could look to it as an authoritative compendium of the laws of Israel. The Mishneh Torah concludes with a vision of Messianic days:

The Sages and Prophets did not long for the days of the Messiah that Israel might exercise dominion over the world ... be exalted by the nations, or that it might eat, drink and rejoice. Their aspiration was that Israel be free to devote itself to the Law and its wisdom, with no one to oppress or disturb it ... in that era there will be neither famine nor war, neither jealousy nor strife. Blessings will be abundant, comforts within the reach of all. The one preoccupation of the whole world will be to know the Lord. "For the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea."

The Arba-ah Turim ends with a citation from the Mishneh Torah:

If one sees his fellow drowning, sees robbers attacking him and can save him, or if one learns that evil doers are conspiring against him, or if one can persuade his fellow not to harm another, and he has not done, he has transgressed the commandment, "Thou shalt not stand idly by the blood of thy neighbor." (Leviticus 19:16). But if one saves another, it is as though he has saved the whole world.

The former is an exalted vision of the "end of days," the latter, ethical instruction, more immediate and more practical. The Mishneh Torah was a classic, the Turim, a code. Both were eventually superseded as the accepted code of Jewish Law by the Shulhan Aruch of Joseph Caro, who prepared for the composition of his great code by writing masterly commentaries on those of Maimonides and Rabbi Jacob, but the code he wrote was an abridged, revised, and refined version of the Turim, not the Mishneh Torah.

|

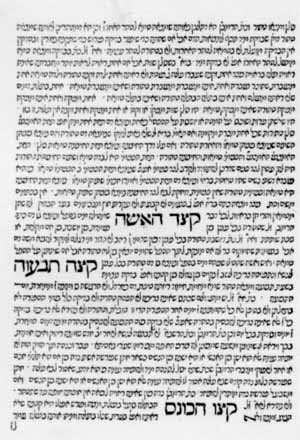

We include Jacob ben Asher's Tur Yoreh Deah, Hijar, 1487, as a representative example of the works inspired by the Mishneh Torah, for the fruits of a tree give evidence of the tree's vitality and creativity.

Sources:Abraham J. Karp, From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, (DC: Library of Congress, 1991)