Great Bibles

The great Bibles written and printed in all the languages of Western man were cherished for their sanctity and admired for their beauty. The Torah and megillah scrolls of the synagogue were essential tools of worship. The Hebrew Bibles, most often printed with commentaries framing the text (the more the better), were the vehicles which took man to an enterprise above worship-study. Diligent study, aided and directed by spiritual giants of the past, revealed God's will to man and unfolded the blueprint of His kingdom on earth. Study of the Bible called for the engagement of the student with one or more of the classical commentators: Solomon ben Isaac (1040-1105) called Rashi, who utilized the Midrashic literature and emphasized moral instruction; Moses ben Nahman, called Ramban and Nachmanides (1194-1270), who laced his interpretations with mysticism; Levi ben Gershom, the Ralbag or Gersonides (1288-1344), whose bent was to philosophy and theology; Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089-1164), a grammarian with a critical turn of mind whose comments sowed the seeds for the critical study of the Bible; or David Kimhi (1160[?]-1235), exponent of philological analysis.

Arguably, the first Hebrew book printed was the Rome (c. 1469-73) edition of the commentary on the Torah of Nahmanides, and the first dated Hebrew book was Rashi's commentary on the Torah, printed in the small Italian town of Reggio di Calabria in 1475. Eleven of the Library's Hebrew incunabula are biblical texts or commentaries: Gersonides's commentary on the Torah, Mantua, 1476 (two copies); Kimhi's on the Psalms, Bologna(?) 1477; Gersonides's on Job, Ferrara, 1477; Rashi's on the Pentateuch, Bologna, 1482; Kimhi's on the Former Prophets, 1485, and the Latter Prophets, 1486, in Soncino (three copies of the latter), his Psalms commentary, Naples, 1487; Nahmanides on the Pentateuch, Lisbon, 1489; Nahmanides on the same, Naples, 1490; a Lisbon, 1491, edition of the Pentateuch, with the translation of Onkelos and the commentary of Rashi; and the Book of Judges with Targum Jonathan and the commentaries of Kimhi and Gersonides, Leiria, 1494.

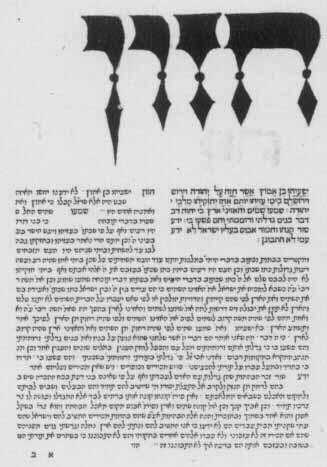

No less than three censors examined this copy of Nevi'im Ahronim (Latter Prophets) with the commentary by David Kimhi, published by Joshua Solomon Soncino in 1486. We show the first page of the Book of Isaiah. The text is in square letters, the commentary in cursive. The large word at the top of the page, the first word of text, Hazon (The Vision), is in manuscript, space having been left by the printer for an artistic illumination to open the book, a provision usual in early printing. Similar space is allotted at the beginning of the other books of the Prophets included in this volume (Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress Photo).

|

Each of these volumes, printed in Italy or on the Iberian peninsula, has survived not only the ravages of time and use, but also the destructive hand of the Inquisition in Portugal, the burning of the Hebrew books in the Papal states in the sixteenth century, and the Church censor's scrutiny and mutilation. Their mere survival, their rescue from enemies, again and again, is an uplifting lesson on the stubborn strength of the human spirit, aided on occasion by nature itself. Thus, the copy of the 1477 Psalms, editio princeps in Hebrew of any portion of the Bible, has come down to us in fine physical condition but heavily censored. Because Kimhi's commentary confronts the Christian claims of Christological foreshadowing in the Biblical text, the censor's pen crossed out every passage deemed offensive to the Faith. An owner of the censored copy later wrote the censored passages in on the margin. Time, which has its own will, also entered the fray fading the censor's ink almost to extinction, but preserving in almost perfect condition the printed text beneath.

David Kimhi's Commentary on the Psalms put the censor on his alert and rarely escaped his heavy hand. This copy of the Bologna(?) 1477 edition of the Psalms and Commentary is heavily censored. But as we can see, what the Papal censor excised an early owner inserted in manuscript. Kimhi's comment at the end of Psalm 72 notes that Jesus could not have been the Messiah, since the messianic prophecy that the Messiah would bring peace was not fulfilled; as Kimhi states, "there was no peace in the time of Jesus." Beginning with the sixteenth century, Jewish publishers exercised self-censorship when printing the Kimhi Commentary (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

Among the above-listed volumes are a number of significant firsts. The Bologna(?) 1477 Psalms is the first Hebrew book printed in that city, as are for their cities the 1487 Psalms of Naples and the Gersonides commentary on Job, 1477, of Ferrara.

Joseph ben Jacob of Gunzenhausen, a town in Southern Germany, arrived with his son Azriel in Naples in 1486 and soon set up a Hebrew printing house there. They were among a good number of Jews from other cities in Italy and the Iberian Peninsula, who were attracted to that port city by the welcome extended by King Ferdinand I. The first of the twelve volumes published by the Gunzenhausens, father, son and daughter, was the Psalms, again as in Bologna, with the Commentary of David Kimhi. In this edition, however, the text is separated from the Commentary, not only by different typography, but by the organization of the page as well. It is worthy of note that the recent arrivals felt secure enough in their new home to publish Kimhi's Commentary (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

In 1516, a wealthy Venetian, Daniel Bomberg who had been born in Antwerp, was granted the privilege of publishing Hebrew books in that city. Among the first he published was a folio edition of the entire Bible with the leading commentaries, Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible), which came off the press in 1516-17. Pope Leo's imprimatur was sought and granted, and Felix Pratensis, a monk born a Jew, was its editor. Bomberg published the edition because of growing interest in the Hebrew language and the Bible among learned Christians. As a good businessman, he quickly perceived that there was a substantial market for Hebrew texts among the Jews of Italy, whose numbers had been increased by an influx of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish exiles. The commentaries of Rashi, Kimhi, Nahmanides, and Gersonides attracted the Jewish clientele, but the editorship by an apostate and the blessing of the Pope made Jews avoid the edition, so Bomberg quickly published a quarto edition, without any mention of either editor or sponsor. Six years later in 1524, his second Rabbinic (i.e., with commentaries) Bible appeared. This time Bomberg emphasized that his printers were pious Jews, as was his scholarly editor. In time more than two hundred Hebrew books came off the Bomberg press, volumes of singular scholarly merit and typographical excellence.

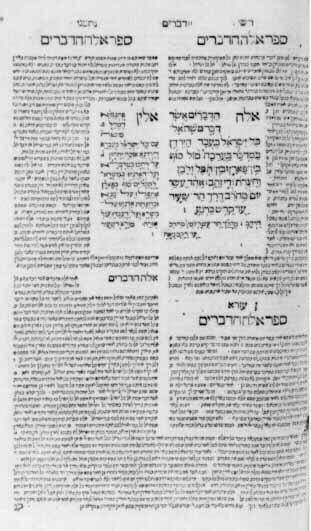

The first Rabbinic Bible, i.e., the biblical text accompanied by a number of commentaries, was published by the greatest of Hebrew printers in the sixteenth century, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian from Antwerp, who set up his Hebrew press in Venice in 1515 and published some 230 works. Published in 1517 and edited by the apostate Felix Pratensis who dedicated it to Pope Leo X, it apparently did not attract the anticipated Jewish audience, hence a new edition, seven years later, edited by Jacob ben Hayim, who wisely chose to print the Masoretic text. The latter edition became the standard for all future printings of the Hebrew Bible. It is opened to the end of the Book of Samuel and the first verses of the Book of Kings (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

Far larger numbers of Jewish exiles from the Iberian peninsula found haven in the Ottoman Empire than on the Italian peninsula. They brought a scholarly presence to Constantinople and established a great Jewish community in the port city of Salonica. in both cities presses were established which did much to make the Ottoman Empire a seat of Jewish scholarship. In 1522 a fine edition of the Pentateuch, with the classic commentaries Perush ha-Torah le-Rabi Moshe bar Nachman, was published in Constantinople. What is of particular interest is that both the biblical text and the Onkelos Aramaic translation are not only vocalized but have cantillation notations as well. The doyen of Hebrew bibliographers, Moritz Steinschneider, accords it the accolade summae raritatis. The Library also has a copy of the Psalms with commentary, printed in the same year in Salonica, which is equally rare.

The greatest of Hebrew bibliographers, Moritz Steinschneider, called this edition of the Pentateuch "of highest rarity." The page before us, the opening verses of Deuteronomy, has the text in the center in large square letters. Next to it is the Aramaic translation by Onkeles. At the outer margin is the commentary of Nachmanides, and on the inner, the commentary of Rashi above, and that of Abraham Ibn Ezra below. it was published in two editions, one for the Sefardi community, the other for the Karaite. The Library's copy is for the former (Hebraic Section, Library of Congress Photo).

|

The most beautiful Hebrew Bible published in the sixteenth century is Robert Estienne's 1539-44 edition, printed in Paris. For five years Estienne had been the king's printer for Hebrew, and this edition is regal indeed. The Library's copy came with the Rosenwald Collection and is in pristine condition. One marvels not only at the beauty of the Le Bé type and the symmetry of the printed page, but at the whiteness of the paper and the jet-black type as well. What adds further interest to this set of volumes is that they bear the ownership plates of Mortimer Schiff, bibliophile son of philanthropist Jacob H. Schiff, who acquired two Deinard Collections of Hebraic imprints for the Library of Congress.

The typographical artistry of Guillaume Le Bé and the printing skill of the Estienne family, Royal Printers in Paris, combined to fashion this work of singular typographical distinction. The twenty-four parts of the Hebrew Bible, bound in four volumes in green morocco for Charles III, Cardinal of Bourbon, have come down in pristine condition. Now a part of the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, they were formerly owned by Mortimer J. Schiff, son of Jacob H. Schiff, who presented two Deinard Hebraica Collections to the Library of Congress (Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress Photo).

|

Of equal interest, but for quite another reason, is the Elias Hutter Hebrew Bible, Hamburg, 1587. Hutter's concern was neither for correctness of text nor beauty of typography, though he succeeded in both. His was a more practical, scholarly mission—to make the Hebrew Bible more readily accessible to the student. He therefore used two forms of type—a solid letter for the root and a hollow letter for the prefixes and suffixes, which give the page an aesthetically pleasing and subtle shading. Handsome indeed are both the engraved title page and the adorned introduction. The Library's copy is enhanced by a fine binding, as well as vellum marker tabs attached to the title pages of the individual biblical books.

The Hutter Bible was designed to serve the student of the Hebrew language as well as the student of the Bible. Shown here are the title page from the 1587 edition of Elias Hutter's Bible as well as the engraved opening page from the 1603 reissue of that work. Note the solid and hollowed-out Hebrew letters on the title page; the solid type signifies the root letters of the word, while the hollow type is used to indicate prefixes and suffixes (Library of Congress Photo).

Sources: Abraham J. Karp, From

the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress,

(DC: Library of Congress, 1991).

|