|

IOWAIOWA, state in midwestern U.S. In 2005 Iowa had a Jewish population of 6,100 out of a total of 2,944,000. The largest Jewish community was in Des Moines (3,500), the state capital, where there were four synagogues – Orthodox, Conservative, Reform and Chabad – a Jewish Federation which is situated on the community campus and includes Iowa Jewish Senior Life Center, a synagogue, and the Community Hebrew School. There were also organized Jewish communities with one or more synagogues in Ames, Cedar Rapids, Waterloo, Council Bluffs; Davenport (450); Dubuque (105); Iowa City (200), Sioux City (300), and Postville, now home to 450 Jews, most associated with the kosher meat processing plant, AgriProcessors. The first mention of Jews in connection with Iowa appeared in a memoir published in London in 1819 by William Robinson, a non-Jewish adventurer and land speculator, who proposed mass colonization of European Jews in Iowa and Missouri. The first known Jewish settler was Alexander Levi, a native of France who arrived from New Orleans in 1833 and established himself in Dubuque in the year the town was laid out. Credited with being the first foreigner naturalized in Iowa (1837), Levi helped develop the lead mines first worked by Julien Dubuque, for whom the town was named. One of Dubuque's leading citizens for 60 years, Levi was elected justice of the peace in 1846. In the late 1830s and early 1840s Jewish peddlers from Germany and Poland reached Dubuque and McGregor, key points for traffic across the Mississippi, in eastern Iowa, as the immigrant tide began pushing westward. Solomon Fine and Nathan Louis were doing business at Fort Madison in 1842. In that year Joseph Newmark opened a store at Dubuque. Among the early settlers in McGregor were the parents of Leo S. Rowe (1871–1946), director-general of the Pan-American Union (1920–46), who was born there. Samuel Jacobs was surveyor of Jefferson County in 1845. In the 1850s Jews were also settled at Davenport, Burlington, and Keokuk. William Krause, the first Jew in Des Moines, arrived with his wife in 1846, when it was still known as Raccoon Forks. His brother Robert came to Davenport about the same time. Krause opened Des Moines' first store in 1848, a year before Joseph and Isaac Kuhn arrived there. Krause was one of the incorporators of Des Moines, helped found the town's first public school, contributed toward the building of Christian churches, and was a leading figure in having the state capital moved from Iowa City to Des Moines. Other pioneer Jews were Michael Raphael, paymaster of the Northwestern Railroad while it was building west from Davenport; Abraham Kuhn, who went to Council Bluffs in 1853; Leopold Sheuerman, who had a store at Muscatine in 1858; and Solomon Hess, who represented Johnson City at the 1856 convention at which the Iowa Republican Party was organized. The first organized Jewish community was formed at Keokuk in 1855 in the home of S. Gerstle under the name of the Benevolent Children of Israel. This society maintained a cemetery from 1859 on and four years later was incorporated as Congregation B'nai Israel. In 1877 it erected Iowa's first synagogue. Other communities grew up in Dubuque and Burlington in 1857 and in Davenport in 1861. There was a handful of Jews in Sioux City on the banks of the Missouri River in the 1860s, but no congregation was formed until 1884. The Council Bluffs community dates from the late 1870s and that in Ottumwa from 1876. Davenport's Temple Emanuel is the oldest existing congregation (the one in Keokuk went out of existence in the 1920s). Des Moines' pioneer congregation, B'nai Jeshurun, was founded in 1870 and erected the state's second synagogue in 1878. The best-known Jews in Iowa in the 1880s were Abraham Slimmer, of Waverly, and Moses Bloom, of Iowa City. Slimmer, a recluse, endowed hospitals, schools, and orphanages throughout Iowa and other states and was a generous contributor to synagogues. Bloom was elected mayor of Iowa City in 1869 and 1874 and served in both houses of the state legislature in the 1880s. Benjamin Salinger served on the Iowa State Supreme Court from 1915 to 1921. Joe Katelman was elected mayor of Council Bluffs in 1966. David Henstein was mayor of Glenwood (1892) and Sam Polonetzky was mayor of Valley Junction (1934). [Bernard Postal] Des Moines remains the largest center of Jewish life in Iowa. Its Federation, located on a community campus which includes the Jewish Community Relations Commission, the Greater Des Moines Jewish Press, Jewish Family Services, the Iowa Jewish Senior Life Center, and Tifereth Israel, the Conservative synagogue which houses the Federation-run community

Hebrew School, is very active and influential. The Des Moines Jewish Academy, a day school started in 1977 by three families, merged in 2004 with a secular private school to become The Academy, Des Moines' only secular private school. The Academy offers an after-school Jewish curriculum. An additional Federation facility for social, cultural, and recreational activities, the Caspe Terrace, located in nearby Waukee, Iowa, is the site of the children's camp, Camp Shalom, as well as the museum of the Iowa Jewish Historical Society, a committee of the Federation founded in 1989. Des Moines boasts four synagogues, and ritual practice in most has become more traditional over time. The Reform Temple, B'nai Jeshurun, has the largest membership with Shabbat services now held on both Friday night and Saturday morning. Ritual at the Conservative synagogue, Tifereth Israel, has remained largely unchanged. Beth El Jacob, the Orthodox synagogue which allowed mixed seating beginning in the 1950s, now has a meḥizah in both its small chapel and its main sanctuary. Lubavitch of Iowa/Jewish Resource Center, operating with its current rabbi since 1992, holds Shabbat services and publishes a monthly magazine, The Jewish Spark, and contains a mikveh, as does Beth El Jacob synagogue, less than half a mile away. Beth El Jacob synagogue and Lubavitch of Iowa clashed over a bequest, which resulted in a civil law suit. The resulting settlement led to the establishment of a Chabad-run kosher deli, Maccabee. The Jewish population in Des Moines has moved westward. With the purchase of land west of Des Moines, plans are under discussion for moving the campus that contains both the Federation and Tifereth Israel synagogue. Perhaps the most interesting development in Iowa has been the growth of an ultra-Orthodox community in rural Postville, where once there were only Christians. Heshy Rubashkin moved to this town of 2300 in 1989 to set up AgriProcessors, a kosher meat processing plant. Five years later, when they opened a Jewish school, more ḥasidic families followed. Today 75 ḥasidic families live in Postville, which offers K-8 Jewish education for girls and K-11 Jewish education for boys. The Postville Jewish community boasts a Jewish doctor, a family-run kosher cheese manufacturing business, Mitzvah Farms, and a kosher grocery store and adjacent restaurant. Tensions developed between the ḥasidic newcomers and their Christian neighbors. The cross cultural conflict became the subject of much national press coverage, a bestselling book, and a PBS movie. Though tensions still persist, Jews and non-Jews are learning to live with each other. One member of the hasidic community was elected to a term on the Postville City Council. Recently the Lubavitch community, which houses Postville's only synagogue where all types of Ḥasidim pray together, including those of Ger and Bobov, opened a Jewish Resource Center. The JRC, open to all comers including non-Jews, contains a Jewish library, meeting room, gift shop and offers Jewish tutorials for the few non-observant Jews in Postville. One Postville resident, observing the harmony among diverse Ḥasidim described life in Jewish Postville as "moschiah time." Sioux City, which was at one time Iowa's second largest Jewish community, now numbers only 300. To address the crisis of a Jewish population decreasing through death and not replenishing with new families, the Conservative and Reform synagogues merged in 1994, maintaining in congregation Beth Shalom affiliation with both the Conservative and Reform movements. Ritual observance at Beth Shalom generally follows the Reform tradition, though Conservative traditions apply to both Shabbat morning and second day holiday prayer. Beth Shalom maintains a K-12 religious school and employs a full-time rabbi, ordained at a trans-denominational seminary. In Iowa City, home to the University of Iowa, the Reform and Conservative synagogues also merged, and congregation Agudas Achim, with a membership of 200 families, is affiliated with both the Reform and Conservative movements. Services, led by a Conservative-ordained Rabbi, generally follow the Conservative ritual, though once each month Reform services are held. The University of Iowa with a Jewish population of roughly 600 undergraduates and 200 graduate students runs a Hillel in which about 10% of the students are active. Nearby, Temple Judah of Cedar Rapids, a Reform Congregation, has maintained a stable Jewish community with 125 families and a school enrollment of 53 students. Davenport, one of the Quad Cities, has a Jewish population of about 450 people, most affiliated with either the Reform Congregation, Temple Emanuel, or a Conservative synagogue across the river in Rock Island, Illinois. An Israeli shali'aḥ sent to Davenport's Federation for one year, has helped revitalize Jewish life and promote outreach to the non-Jewish community. Ames, the home of Iowa State University, maintains the Ames Jewish Congregation, a community of 62 families, affiliated with the Reform Movement since 1962. BIBLIOGRAPHY:J.S. Wolfe, A Century with Iowa Jewry (1941); S. Glazer, Jews of Iowa (1904); B. Postal and L. Koppman, A Jewish Tourist's Guide to the U.S. (1954), 171–77. Steven Bloom, Postville: A Clash of Cultures in Heartland America (2001); Yiddl in Middle: Growing Up Jewish in Iowa, a film by Marlene Booth. [Marlene Booth (2nd ed.)] Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved. |

|

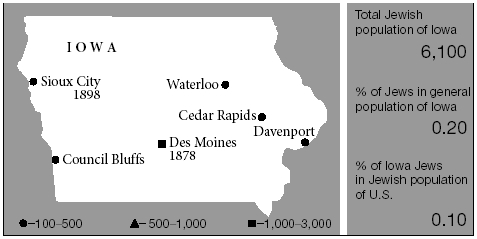

Jewish communities in Iowa, with dates of establishment of first synagogue. Population figures for 2001.

Jewish communities in Iowa, with dates of establishment of first synagogue. Population figures for 2001.