|

EZRA AND NEHEMIAH, BOOKS OFEZRA AND NEHEMIAH, BOOKS OF, two books in the Hagiographa (i.e., the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah), which were originally a single work. The Masoretic tradition regarded the books of Ezra and Nehemiah as one book and referred to it as the Book of Ezra. This was also the Greek tradition, and the same Greek name, Esdras, was given to both books (see below). The division into separate books does not occur until the time of Origen (fourth century C.E.) and this division was transferred into the Vulgate where the books are called I Esdras (Ezra) and II Esdras (Nehemiah). It was not until the 15th century that Hebrew manuscripts, and subsequently all modern printed Hebrew editions, followed this practice of dividing the books. However, there are good reasons (linguistic, literary, and thematic) for the argument that the two books were originally separate works (Kraemer), which were brought together by a later compiler, and are now to be read as a single unit (Grabbe). Place in the CanonThere are two traditions regarding the place of Ezra-Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible. The more dominant Babylonian tradition, which is followed by all modern printed editions, places Ezra-Nehemiah immediately before Chronicles, the last book of the Writings. However, the Palestinian tradition, which is found in major Tiberian manuscripts, such as Aleppo and Leningrad, places Chronicles first in the Writings (before the Psalms), and places Ezra-Nehemiah last. In the Protestant Old Testament (e.g., the NRSV version), Ezra-Nehemiah is placed among the historical books, after Chronicles and before Esther. In the Roman Catholic Old Testament (e.g., the Douay-Rheims version), the books are similarly placed after Chronicles but before Tobit, Judith, and Esther. Text and VersionsSome Hebrew fragments from the Book of Ezra (4QEzra) were found in Cave 4 at Qumran (Ulrich). The fragments contain part of the text of Ezra 4:2–6, 9–11, and 5:17–6:5 and exhibit two orthographic variants (e.g., at Ezra 4:10, 4QEzra reads נַהֲרָא for MT's נַהֲרָה), and two minor grammatical variants concerning singular and plural forms of verbs (e.g., at Ezra 6:1 where 4QEzra reads the singular ובקר "he searched" for MT's וּבַקַּרוּ "they searched"). The Greek tradition knew of two versions of Ezra-Nehemiah, one of which is known as II Esdras, and is a very literal translation of the Hebrew. This version numbers Ezra-Nehemiah consecutively so that chapters 1–10 of II Esdras represent the Book of Ezra, and chapters 11–23 represent the Book of Nehemiah. However, the other version, known as I Esdras, is wholly concerned with Ezra and not Nehemiah. It offers a rendering of the entire Book of Ezra but translates only that portion of the Book of Nehemiah (7:72–8:13) which deals with Ezra. This additional section is attached directly to what is chapter 10 in the Masoretic version. Languages of the BooksThe language of Ezra-Nehemiah is late biblical Hebrew (Polzin) and the text exhibits features which are characteristic of this later language. These include use of the -ו consecutive with the cohortative (וָאֶשְׁלְחָה), increased use of pronominal suffixes to the verb (וַיִּתְּנֵם) and of הָיָה with the participle (אֹמְרִיםהָיוּ), many Akkadian and Persian loan words (such as אִגֶּרֶת "letter" = Akk. egirtu; פַּרְדֵּס "garden" = Pers. pairidaeza), and many Aramaisms (Naveh and Greenfield). Parts of Ezra are written in Aramaic (4:8–6:18, 7:11–26), and it has been suggested that originally the entire book of Ezra-Nehemiah was written in Aramaic and was subsequently translated (Marcus). In support of this theory is the fact that there is no extant Targum for Ezra-Nehemiah.

Authorship and DateThe question of the authorship of Ezra-Nehemiah is bound up with its relation with the book of Chronicles. Since the time of Zunz (1832), the consensus of modern scholarship has been that the author of Chronicles was also the author of Ezra-Nehemiah, and this view still has its adherents (Blenkinsopp, Clines (1984)). Arguments for joint authorship include common vocabulary, style, uniformity of theological conceptions, similar description of religious ceremonies, penchant for occupational and genealogical lists, and, most importantly, the fact that the first few verses of Ezra (1:1–3a) are identical to the last two verses of Chronicles (II Chron 36:22–23), thus indicating that Chronicles leads in by means of catchlines to the following Book of Ezra (Haran). The position of Ezra-Nehemiah before Chronicles in the Protestant and Catholic Old Testament canons would seem to lend support for this point of view. In recent times, however, the independent authorship of both works has been argued on the basis of the following perceived contrasts: that Chronicles glorifies David, highly regards prophecy, has a conciliatory view of Northerners, and a miraculous view of history, whereas Ezra-Nehemiah emphasizes Moses and the Exodus, is forceful about its opposition to the Northerners (Samaritans), and has a different view of history. Ezra-Nehemiah ought then to be dated to the end of the fifth century B.C.E. whereas Chronicles is a later book composed at the end of the fourth century B.C.E. (Japhet). The catchlines at the end of Chronicles were borrowed from Ezra to give the book of Chronicles an "upbeat" ending heralding Cyrus' decree, and so not ending with the exile of the people in Babylon (Williamson). Contents of the BooksEzra-Nehemiah deals with the period of the restoration of the Jewish community in Judah, then the Persian province of Yehud, in the sixth–fifth centuries B.C.E. during the approximately 100 years between the time of the edict of *Cyrus (538) permitting the Jews to go back to Jerusalem and the 32nd year of the reign of *Artaxerxes I (433). Three different periods are represented in the books, each with different leaders and different royal missions. The first period (Ezra, chaps. 1–6) goes from the time of the edict of Cyrus (538) until the rebuilding of the temple (516), when the leaders of the Jews were Sheshbazzar and Zerubbabel. The second period (Ezra, chaps. 7–10 and Neh., chap. 8) commences in the seventh year of the reign of Artaxerxes (458), when Ezra is given a royal mandate to lead a group of exiles back to Jerusalem. The third period (Neh., chaps. 1–7 and 9–13) encompasses a 12-year period from the 20th year of the reign of Artaxerxes (445) until his 32nd year (433), and deals with the work of Nehemiah. THE FIRST PERIOD (EZRA, CHAPS. 1–6)The first period, embracing 22 years from 538 to 516, includes an account of (1) the edict of Cyrus; (2) a list of the first returnees; (3) restoration of worship and laying foundations of the Temple; (4) opposition to the Temple building; (5) the appeal to *Darius and his favorable response; and (6) the completion of the Temple. In this period the leaders were *Sheshbazzar and *Zerubbabel. Sheshbazzar is thought to be identical with Senanazzar (the fourth son of Jeconiah (Jehoiachin), I Chron. 3:18), and is termed both prince (נָשִׂיא) and governor (פֶּחָה). Zerubbabel is one of the leaders of the first émigrés (2:2), and probably succeeded Sheshbazzar (4:2), though both are said to have laid foundations of the Temple (Sheshbazzar in Ezra 5:16 and Zerubbabel in Zech. 4:9). The Edict of Cyrus (1:1–11)There are two accounts given in the Book of Ezra of the edict of Cyrus: a Jewish version in Hebrew, and a Persian version in Aramaic. The Jewish/Hebrew version has Cyrus declare that God has given him "all the kingdoms of the earth," that He has ordered the reconstruction of the Temple, and that any of God's people who so wish may return to assist in the carrying out of the order (1:1–3). The Persian/Aramaic version gives extra details detailing the specifications of the Temple to be built (e.g., its height and width should be 60 cubits, emulating the Temple destroyed by the Babylonians), that expenses for the Temple will be paid by the state, and that precious utensils captured by *Nebuchadnezzar and brought to Babylon will be returned (6:3–5). This last fact is actually mentioned in the first chapter of Ezra (v. 7). Cyrus released the cult objects and delivered them to Sheshbazzar, the governor of Judah, via Mithredath, the state treasurer. The Cyrus cylinder records similar acts of amnesty and favor shown to the peoples and deities of other countries following his conquest of Babylon in 539 (Cogan). A List of the First Returnees (2:1–3:1)The list of the returning exiles with Zerubbabel is itemized by family, place of origin, occupation (e.g., priests, Levites, singers, gatekeepers, etc.). Because this list is repeated in its entirety in Nehemiah (Neh. 7:6–8:1a) there has been much discussion of the list's purpose, and where the list originally belonged. Most likely, the writer in the Book of Ezra was using a later list compiled for other uses, and its purpose at the beginning of Ezra is to magnify the first response of the exiles to Cyrus' edict. However, in the Book of Nehemiah, the list is used for a different purpose, as a starting point of a campaign to induce those who had settled elsewhere in Judah to move to Jerusalem, which needed repopulation. Restoration of Worship and Laying Foundations of the Temple (3:2–13)Among the first activities of the returning exiles in 538 were to erect an altar on the site of the Temple, renew sacrificial worship, and celebrate the festival of Tabernacles. Preparations were then made for the rebuilding of the Temple, parallel to the preparations made for Solomon's Temple. The laying of the foundations was performed with a special service: prayer and song. The people's response was enthusiastic and they wept out of joy. However, there were a number of the returned exiles who had seen the first Temple, and these people wept in memory of this destroyed Temple to such an extent that the weeping for joy could not be distinguished from those weeping in memory of the destroyed Temple. Opposition to the Temple Building (4:1–24)Work on the Temple did not proceed smoothly and, although it was started in the second year after the return (537), work was not continued on it until the second year of Darius I (521). The long delay of some 21 years between the laying of the Temple's foundations in 537 and its completion in 516 is explained as due to opposition by the local population. The opposition arose primarily as a result of the exclusionary policy of the returnees about permitting the indigenous population to participate in the rebuilding effort. The returnees believed that they were the true representatives of the people of God who had gone into exile, and that those who had not gone into exile but remained in the land, or were descendants of displaced peoples who had subsequently adopted Israel's religion, were not entitled to join in this project. The opponents are called צָרֵי יְהוּדָה וּבִנְיָמִן "adversaries of Judah and Benjamin" and עַם־הָאָרֶץ "people of the land," and they attempted to thwart the rebuilding effort by various means including writing accusatory letters to the Persian kings. These accusatory letters contained in 4:6–23 are problematic on two counts: first, because they do not deal with the rebuilding of the Temple but with the rebuilding of the city, and second because these letters are addressed to Persian kings who reigned long after the Temple was actually completed (516). These letters are sent to *Xerxes I (486–465) and *Artaxerxes I (465–424). That the section containing these letters is misplaced is clear from the fact that it is put in a different place in I Esdras, where these letters occur in chapter 2, and not in chapter 4 as in the Masoretic text. Appeal to Darius and Favorable Response (5:1–6:14)The end of chapter 4 reverts back to the proper chronology, that of the second year of Darius (521), at which time the prophets *Haggai and *Zechariah encouraged the Jews to persist in the building of the Temple. The renewed activity led to an investigation by local Persian authorities, and a letter of inquiry (not a complaint like the preceding communications) was sent to Darius. The Persian authorities reported that they had gone to Jerusalem, observed the state of building operations, and had requested information on the authorization of the project. They were informed by the Jewish leaders of the edict of Cyrus granting the Jews permission to rebuild the Temple, and the letter asked the king to verify whether or not Cyrus did issue this edict. Darius then ordered a search in the royal archives, and the edict was found and is reproduced in his reply to the local authorities (see above). Darius issues instruction that the Cyrus decree be honored, and that expenses for the project be defrayed from the tax income accruing to the royal treasury from the province. Moreover, provisions were to be made for daily religious observances so that prayers could be made for the welfare of the king and his family. The aforementioned Cyrus Cylinder is often pointed to as an example of a Persian monarch who requested prayer from other peoples for his own and his son's welfare. Completion of the Temple (6:15–22)The reconstruction on the Temple was completed in the sixth year of the reign of Darius I (516); the work had taken 21 years since the foundation was laid in the second year of Cyrus (537). A joyful dedication ceremony took place with enormous amounts of sacrifices, "one hundred bulls, two hundred rams, four hundred lambs, and twelve goats." Shortly afterwards the returned exiles celebrated the Passover, together with those of the indigenous population who had "separated themselves from the uncleanliness of the nations of the lands," a hint that the returnees were open to permitting others into their fold (see also Neh. 10:29). THE SECOND PERIOD (EZRA, CHAPS. 7–10 AND NEH., CHAPS. 8–9)The second period dated in the seventh year of the reign of Artaxerxes I (458) deals with the work of *Ezra, after whom the book was named, and includes (1) the edict of Artaxerxes to Ezra; (2) Ezra's return to Jerusalem; (3) his reaction to news of intermarriage; (4) his reading of the Torah; and (5) a day of penance and a prayer of the Levites. In this period, the leader is Ezra, a priest whose ancestry is traced back to Aaron (7:1–5), and a scribe "well versed in the law of Moses" (7:6, 11). The date of Ezra is problematic as is his relationship with *Nehemiah, because apart from Nehemiah 8:9, and two other minor references (Neh. 12:26, 36), the two are never mentioned together. According to their respective books, Ezra assumed his mission in the seventh year of Artaxerxes (458) and Nehemiah came in the 20th year of the same king (445). This would mean that Ezra, who came at the express command of Artaxerxes to implement and teach the law, did not conduct his first public reading of the Law until 13 years later. Another problem for the biblical chronology is that Ezra found many people in Jerusalem but, according to Nehemiah, in his time, Jerusalem was unpopulated. For these reasons and others, some scholars believe Ezra came to Jerusalem much later, either in the 37th year of Artaxerxes I (428) or in the seventh year of Artaxerxes II (397) (see discussion in Klein). The Edict of Artaxerxes to Ezra (7:1–28)In the seventh year of his reign (458), Artaxerxes I (465–424) issued a royal edict granting permission for Jews to go to Jerusalem with Ezra. Ezra was permitted to bring with him gold and silver donations from other Jews. Regular maintenance expenses of the Temple were to be provided from the royal treasury and there was to be release of taxes for Temple personnel. Ezra's mission was "to expound the law of the Lord" and "to teach laws and rules to Israel" (v. 10). For this purpose he was granted, not only a royal subsidy, but he was also empowered to appoint judges, enforce religious law, and even to apply the death penalty. In response to critics who argue that such a concern by a Persian king for a foreign cult would be unlikely, the Passover papyrus issued by Darius II in 419/18 to the Jews at Elephantine in Egypt regarding the date and method for celebrating the Passover (Porten) has often been cited. Nevertheless, the question of imperial authorization of Jewish law by the Persian Empire continues to be a subject of debate (Watts). Ezra's Return to Jerusalem (8:1–36)Ezra's four-month journey to Jerusalem is described by Ezra in a first-person memoir. After listing the names of the leaders returning with him, Ezra discovers there were no *Levites in his party so he had to muster up 38 Levites from some Levitical families. Another problem was security. Because Ezra had originally made a declaration of trust in God before the king, he felt it inappropriate to request from him the customary escort. Thus he accounted the party's safe arrival in Jerusalem with all its treasure intact as a mark of divine benevolence. Ezra's Reaction to News of Intermarriage (9:1–10:44)When Ezra arrived in Jerusalem he was informed that some people, including members of the clergy and aristocracy, had contracted foreign marriages. Immediately upon hearing this news Ezra engaged in mourning rites, tore his garments and fasted, and, on behalf of the people, confessed their sins and uttered a prayer of contrition. He is joined by a group of supporters who are also disturbed by this news. At the initiative of a certain Shecaniah son of Jehiel, Ezra was urged to take immediate action. An emergency national assembly was convened, and Ezra addressed the crowd in a winter rainstorm calling upon the people to divorce their foreign wives. The assembled crowd agreed to Ezra's plea, but because of the heavy rains and the complexity of the matter (Ezra's extension of legal prohibitions of marriages that had previously been permitted), they requested that a commission of investigation be set up. After three months the commission reported back with a list of priests, Levites, and Israelites who had intermarried. Ezra's Reading of the Torah (Neh 8:1–12)Seemingly out of order, Ezra reappears in chapter 8 of the Book of Nehemiah where it is recounted that he publicly read the Torah on the first day of the seventh month (Rosh Ha-Shanah). He stood upon a platform with dignitaries standing on his right and left. The ceremony began with an invocation by Ezra and a response by the people saying "Amen, Amen." During the reading the people stood while the text was made clear to them (or translated for them (into Aramaic)) by the Levites (van der Kooij). The people were emotionally overcome by the occasion and wept. However, they were enjoined not to be sad, rather to celebrate the day joyously with eating, drinking, and gift giving. The day after the public reading, a group of priests and Levites continued to study the Torah with Ezra and came across the regulations for observing the feast of Tabernacles on that very month. A proclamation was issued to celebrate the festival which was done with great joy, and the Torah was again read publicly during the entire eight days of the festival. It has often been pointed out that the feast of Tabernacles which is described as being discovered anew from the Torah reading and had not been observed since the days of Joshua, had already been observed not too much earlier by the first return-ees (Ezra 3:4). Furthermore, the materials said to be collected for the festival (branches of olive, pine, myrtle, palm, and leafy trees) differ from those mandated for the festival in Leviticus 23:40 (where the materials are the fruit of הָדָר trees (later interpreted as the citron), willows of the brook, palms, and bough of leafy trees (later interpreted as the myrtle)). Most strikingly, these materials are said to be used to construct סֻכּׁת "tabernacles," and not to be used for making of the לוּלָב and אֶתרוֹג in accordance with the later rabbinic interpretation. Day of Penance and Prayer of the Levites (Neh. 9:1–37)On the 24th day of the month, immediately after the celebration of the feast of Tabernacles, a fast day was announced. The identification and purpose of this fast day is unknown. Most commentators believe that this fast and following prayer of the Levites THE THIRD PERIOD (NEH., CHAPS. 1–7 AND 9–13)The third period encompasses 12 years from the 20th year of the reign of Artaxerxes I (445) until his 32nd year (433), and deals with the work of Nehemiah, who had held an important office (termed a "cupbearer") in the royal household of the Persian king Artaxerxes I (465–424). The work of Nehemiah described in the form of a first-person memoir includes his rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem and his economic and religious reforms. One of the characteristics of Nehemiah's memoirs is that he intersperses short direct prayers within his narrative usually starting with זָכְרָה לִי אלֱֹהַי or with slight variations (5:19, 6:14, 13:14, 22, 29, 31) but once with שְׁמַע אֱלֹהֵינוּ (3:36–37). In particular, this period deals with (1) Nehemiah's response to the news from Jerusalem; (2) Nehemiah's efforts at reconstructing and fortifying Jerusalem; (3) intrigues against Nehemiah; (4) the dedication of the wall; (5) Nehemiah's resolution of economic problems; (6) Nehemiah's religious reforms. Nehemiah's Response to News from Jerusalem (1:1–2:9)In the 20th year of the Persian king Artaxerxes I (445), a delegation of Jews arrived from Jerusalem at Susa, the king's winter residence, and informed Nehemiah of the deteriorating conditions back in Judah. The walls of Jerusalem were in a precarious state and repairs could not be undertaken (since they were specifically forbidden by an earlier decree of the same Artaxerxes (Ezra 4:21)). The news about Jerusalem upset Nehemiah, and he sought and was granted permission from the king to go to Jerusalem as governor and rebuild the city. This change in Persian policy is thought to have come after the Egyptian revolt of 448 when it was believed that a relatively strong and friendly Judah could better serve Persia's strategic interests (Myers). Nehemiah was also granted much material assistance including supplies of wood for the rebuilding effort. However, unlike Ezra, Nehemiah requested a military escort for safe conduct throughout the provinces of the western satrapies. Nehemiah's Efforts at Reconstructing and Fortifying Jerusalem (2:10–4:17, 7:1–4)A short time after his arrival in Jerusalem Nehemiah made a nocturnal inspection tour of the city walls riding on a donkey. He relates that he could not continue riding, but had to dismount, because of the massive stones left by the overthrow of the city by the Babylonians. After his tour of inspection, Nehemiah disclosed to the local Jewish officials his mission to rebuild the walls. Nehemiah set to the task of rebuilding the wall by dividing the work into some 40 sections. Nearly all social classes (priests, Levites, Temple functionaries, and laypeople) participated in the building effort. Throughout the time of the building, Nehemiah encountered opposition and harassment from the leaders of the Persian provinces, who had previously administered the affairs of Judah, especially from one *Sanballat, a Horonite (from Beth Horon), also termed the Samarian/Samaritan. Sanballat resorted to mockery and ridicule, stating: "that stone wall they are building – if a fox climbed it he would breach it" (3:33–35). To counter the opposition, Nehemiah provided a guard for the workmen, and the masons and their helpers also carried swords. Because of the magnitude of the project, the workmen were separated from each other by large distances, so a trumpeter was provided ready to sound the alarm, the idea being that should one group be attacked the others would come to their aid. Nehemiah ordered the workers to remain in Jerusalem partly for self-protection and partly to assist in guarding the city. After the wall was rebuilt, Nehemiah appointed Hanani his brother and a similar-named individual, Hananiah, to be in charge of security. He also gave an order that the gates to the city should be closed before the guards went off duty and that they should be opened only when the sun was high (at midmorning). In addition to the security police, there was a citizen patrol whose duty it was to keep watch around their own houses. The central problem was the small population of Jerusalem: the city was extensive and spacious, but the people it in were few, and the houses were not yet built. Nehemiah decided to bring one of ten people from the surrounding population into Jerusalem (11:1–2). Intrigues against Nehemiah (6:1–19)One of Nehemiah's enemies, Tobiah, an Ammonite, had intermarried with a prominent family in Judah. He had tried unsuccessfully to subvert Nehemiah's work by enlisting their aid, but without success. Since Nehemiah's enemies could not prevent the rebuilding and fortification of the city they made desperate attempts to capture him. One plan was to lure him away from Jerusalem to some unspecified place. Four times they attempted to invite him to "meetings," and each time Nehemiah, knowing their harmful intentions, refused their invitation. When these attempts failed, a fifth attempt was made to hurt Nehemiah by framing him before the Persian authorities with a false report that he planned to have himself proclaimed king in Judah. A sixth attempt to damage Nehemiah was to pay a false prophet, Shemaiah, to lure Nehemiah into the Temple, but Nehemiah, realizing that this was a plot, refused to go. Despite these threats, Nehemiah reports that the wall was completed in just 52 days, which seems to be an incredibly short time for such a monumental task. According to Josephus, the project took two years and four months. Dedication of the Wall (12:27–43)A large gathering of priests, Levites, musicians, and notables assembled from all over Judah Nehemiah's Resolution of Economic Problems (5:1–19)During the period of the rebuilding, the people complained about the scarcity of food and the burden of high taxes. To meet their basic needs, the poor were required to pledge their possessions, even to sell sons and daughters into slavery. Nehemiah reacted angrily against the creditors accusing them of violating the covenant of brotherhood. When his appeal to the creditors voluntarily to take remedial action failed, Nehemiah forced them to take an oath, reinforced by a symbolic act of shaking out his garment, to restore property taken in pledge, as well as to forgive claims for loans. Nehemiah himself alleviated the people's tax burden by refusing to accept the very liberal household allowance for his official retinue which amounted to some 40 shekels of silver a day. Nehemiah's Religious Reforms (10:1–40, 12:44–47, 13:1–29)Nehemiah's religious reforms are found (a) in the so-called Code of Nehemiah; and (b) in the regulations he enacted upon embarking on his second term as governor in the 32nd year of Artaxerxes I (433). Code of Nehemiah (10:1–40)The Code of Nehemiah represents pledges made by the community to observe the Torah, its commandments and regulations. It is preceded by a list of signers including Nehemiah, his officials, the priests, Levites, and prominent family members (1–28). In the Code, the community promised to do seven things: (1) to avoid mixed marriages with the peoples of the land; (2) not to buy from foreigners on Sabbaths and holy days; (3) to observe the sabbatical year; (4) to pay a new annual third shekel temple tax; (5) to supply offerings for the services and wood for the Temple altar; (6) to supply the first fruits, firstlings, tithes, and other contributions to the Temple; (7) to bring the tithes due to the priests and Levites to local storehouses. Regulations Enacted by Nehemiah during his Second Term as Governor (13:1–31)Expulsion of Foreigners (13:1–9). In their continued reading of the Torah the community came across a law (possibly referring to Deut 23:4–6) that Ammonites and Moabites were prohibited from becoming Israelites, and so they resolved to separate from foreigners (עֵרֶב). When Nehemiah returned from an official visit to the Persian court in the 32nd year of Artaxerxes (433) he discovered that the high priest Eliashib had given living quarters in a former storage room of the Temple to one of his old enemies Tobiah, the Ammonite (see above). When Nehemiah returned he evicted Tobiah, discarded all his belongings, and had the chambers purified and restored to their original use. Renewal of Levitical Support (13:10–14)Another consequence of Nehemiah's absence at the Persian court was that the people had stopped giving tithes to the Levites forcing them to return to their villages. Nehemiah took steps to bring back the Levites to Jerusalem by ensuring that outstanding payments, which had not been collected during his absence, would be paid and that future tithes would be regularly given. Enforcing Sabbath Regulations (13:15–22)Nehemiah reports that in his day the Sabbath had been utterly commercialized. People were working in vineyards and on the farms, and Phoenician traders set up shops in Jerusalem on the Sabbath. Nehemiah attempted to put a stop to this Sabbath activity by ordering the gates of the city closed during the Sabbath. Despite his orders, the Phoenician traders camped outside the walls hoping to entice customers to come outside. Problem of Mixed Marriages (13:23–29)As in Ezra's day, Nehemiah had to deal with problems arising from marriages with foreign women. A major concern of his was the fact that the children of these marriages could no longer speak the language of Judah. Nehemiah ordered an end to further intermarriage, but he did not go as far as Ezra who demanded divorce from foreign wives. Significance of the Books for Later JudaismEzra and Nehemiah's actions and decrees may be seen as the beginning of an ongoing reinterpretation of tradition in its application to changing circumstances (Talmon). Ezra's reading of the Torah inaugurated a new element in Jewish life whereby the Torah was read and explicated on regular occasions in public. This public reading also led to the democratization of knowledge of the Torah among Jews, since prior to this event most parts of the Torah were under the exclusive provenance and control of the priests (Knohl). The differences between the formulation of regulations in the Book of Nehemiah and their counterparts in the Torah illustrate the process of legal elaboration necessary to meet contemporary exigencies (Clines, 1981). These differences can be seen in at least three areas: contributions to the Temple, regulations regarding Sabbath observance, and new intermarriage prohibitions. TEMPLE CONTRIBUTIONSSome examples of modifications to Pentateuchal laws introduced in the Code of Nehemiah involve upkeep of the Temple. In Exodus 30:11–16, mention is made of a one-time half-shekel tax. The Code of Nehemiah, however, establishes an annual Temple tax, that of one-third of a shekel. In Leviticus 6:1–6, it is stated that fire should burn continuously on the altar but it does not prescribe the mechanism by which this ought to be done. The Code of Nehemiahdoes this by stipulating how the wood for the altar is to be obtained. In Deuteronomy 14:23–26, it is enjoined that tithes SABBATH OBSERVANCEIn the Pentateuch, the Sabbath law enjoins rest from work (e.g., Ex. 20:8–11; 23:12; and passim), but nowhere defines buying food as work, yet buying food from foreigners on the Sabbath is prohibited in the Code of Nehemiah. According to Amos 8:5, pre-exilic Israelites did not trade on the Sabbath, but the new conditions in Nehemiah's time of foreign merchants coming into Jerusalem on the Sabbath led to this new interpretation of the law. NEW INTERMARRIAGE PROHIBITIONSThe stipulations against intermarriage in Exodus 34:11–16 and Deuteronomy 7:1–4 prohibit intermarriage with Canaanites (Hittites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites). Both Ezra and Nehemiah redefine these old Canaanites (who had long disappeared) as the new Canaanites, the current Ashdodites, Ammonites, and Moabites. It is often thought that Ezra's action insisting on the divorce of foreign wives and their children, together with Nehemiah's concern that the children of these foreign women could not speak the language of Judah, represented a shift in Israelite matrimonial law. Previously offspring of intermarriage was judged patrilineally; now it was to be on the matrilineal principle (for a different view, see Cohen). BIBLIOGRAPHY:J.M. Myers, Ezra, Nehemiah (1965); S. Japhet, "The Supposed Common Authorship of Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah Investigated Anew," in: VT, 18 (1968), 330–71; R. Polzin, Late Biblical Hebrew: Toward an Historical Typology of Biblical Hebrew Prose (1976); S. Talmon, "Ezra, Nehemiah," in: L.K. Crim (ed.), The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Supplementary Volume (1976), 317–28; F.C. Fensham, "Neh. 9 and Pss. 105, 106, 135 and 136. Post-Exilic Historical Traditions in Poetic Form," in: JNSL, 9 (1981), 35–51; D.J.C. Clines, "Nehemiah 10 as an Example of Early Jewish Biblical Exegesis," in: JSOT, 21 (1981), 11–17; J. Naveh and J.C. Greenfield, "Hebrew and Aramaic in the Persian Period," in: W.D. Davies and L. Finkelstein (eds.), Introduction; The Persian Period; The Cambridge History of Judaism, 1 (1984), 115–29; D.J.C. Clines, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther (1984); M. Haran, "Explaining the Identical Lines at the End of Chronicles and the Beginning of Ezra," in: BR, 2 (1986), 18–20; H.G.M. Williamson, "Did the Author of Chronicles Also Write the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah? Clutching at Catchlines," in: BR, 3 (1987), 56–59; J. Blenkinsopp, Ezra-Nehemiah (1988); T.C. Eskenazi, In An Age of Prose: A Literary Approach to Ezra-Nehemiah (1988); A. van der Kooij, "Nehemiah 8:8 and the Question of the 'Targum'-Tradition," in: G.J. Norton and S. Pisano (eds.), Tradition of the Text: Studies Offered to Dominique Barthélemy in Celebration of his 70th Birthday (1991), 79–90; R.W. Klein, "Ezra-Nehemiah, Books of," in: D.N. Freedman (ed.), Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992), 2:731–42; E. Ulrich, "Ezra and Qoheleth Manuscripts from Qumran (4QEzra, 4QQoha, b)," in: E. Ulrich et al. (eds.), Priests, Prophets, and Scribes: Essays on the Formation and Heritage of Second Temple Judaism in Honour of Joseph Blenkinsopp (1992), 139–57; S. Japhet, I & II Chronicles (1993); D. Kraemer, "On the Relationship of the Books of Ezra and Nehemiah," in: JSOT, 59 (1993), 73–92; L.L. Grabbe, Ezra-Nehemiah (1998); D. Marcus, "Is the Book of Nehemiah a Translation from Aramaic?" in: M. Lubetski et al. (eds.), Boundaries of the Ancient Near Eastern World: A Tribute to Cyrus H. Gordon (1998), 103–10; M. Cogan, "Cyrus Cylinder (2.124)," in: W.W. Hallo (ed.), The Context of Scripture (2000), 2:314–16; J.W. Watts (ed.), Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch (2001); B. Porten, "The Passover Letter (3.46)," in: W.W. Hallo (ed.), The Context of Scripture (2002), 3:116–17; S.J.D. Cohen, The Beginnings of Jewishness (1999); I. Knohl, The Divine Symphony: The Bible's Many Voices (2003). [David Marcus (2nd ed.)] Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved. |

|

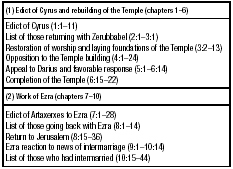

Book of Ezra: Outline

Book of Ezra: Outline

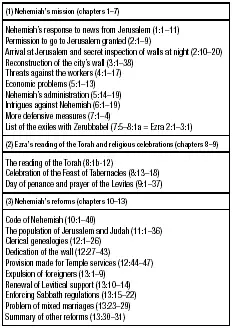

Book of Nehemiah: Outline

Book of Nehemiah: Outline