|

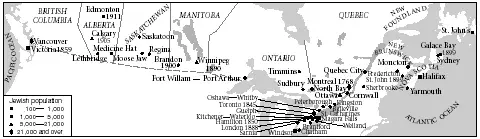

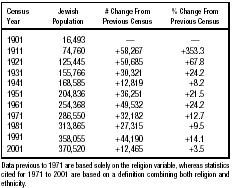

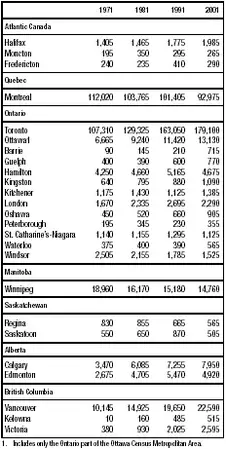

CANADACANADA, country in northern half of North America and a member of the British Commonwealth. At the beginning of the 21st century, its population of approximately 370,000 Jews made it the world's fourth largest Jewish community after the United States, Israel, and France. This Diaspora has been shaped by features that are distinctive to the Canadian nation: French-English duality, the relatively small immigration of German Jews, and proportionally much larger emigration from Eastern Europe. In addition, Canada's Jews have never been subject to a unified, overriding, and jealous Canadian nationalism, which has facilitated the maintenance of a strong sense of Canadian Jewish identity. While American Jewry yearned for integration into the mainstream of the great republic, Canadians expressed their Jewishness in a country that had no coherent self-definition – except perhaps the solitudes and tensions of duality, the limitations and challenges of