|

AUSTRIAAUSTRIA, country in Central Europe. Middle AgesJews lived in Austria from the tenth century. However the history of the Jews in Austria from the late Middle Ages was virtually that of the Jews in *Vienna and its environs. In the modern period, Austrian Jewish life was interwoven with that of other parts of the Hapsburg Empire. Austria's position as the bulwark of the Holy Roman Empire against the Turks, as a transit area between Europe and the Middle East, and later as a center attracting East European Jewry, conferred on Austrian Jewry, and on legal formulations of their status, an importance far beyond its size and its national boundaries. According to legend, a Jewish kingdom named *Judaesaptan was founded in the territory in times before recorded history. Jews apparently arrived in Austria with the Roman legions. They are mentioned in the Raffelstatten customs ordinance (c. 903–06) among traders paying tolls on slaves and merchandise. The earliest Jewish tombstone in the region, found near St. Stephan (Carinthia), dates from 1130. The first reliable evidence of a permanent Jewish settlement is the appointment (1194) of Shlom the Mintmaster. During the reign of Frederick I of Babenberg (1195–98) there was an influx of Jews from Bavaria and the Rhineland. A synagogue is recorded in Vienna in 1204. By then, Jews were also living in *Klosterneuburg, *Krems, Tulln, and *Wiener Neustadt. In the 13th century, Austria became a center of Jewish learning and leadership for the German and western Slavonic lands. Prominent scholars included *Isaac b. Moses, author of Or Zaru'a, *Avigdor b. Elijah ha-Kohen, and Moses b. Ḥasdai *Taku. At this time, Jews held important positions, administering the taxes and mints, and in trade. *Frederick II of Hohenstaufen granted the Jews of Vienna a charter in 1238. In 1244 Duke Frederick II of Babenberg granted the charter known as the "Fredericianum" to the Jews in the whole of Austria. It became the model for similar privilegia granted to the Jews of Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland during the 13th century. *Rudolph of Hapsburg confirmed the charter in 1278, in his capacity as Holy Roman Emperor. It was ratified by the emperors Ludwig IV of Bavaria in 1330 and Charles IV in 1348. Although Jews were excluded by the charter from holding public office, two are mentioned as royal financiers (comites camerae) in 1257. Immigration from Germany increased in the second half of the 13th century, but meanwhile the Jews encountered growing hostility, fostered by the church (for example, by the ecclesiastical Council of Vienna, 1267). Four instances of *blood libel occurred. The massacres of Jews in Franconia instigated by *Rindfleisch spread to Austria. Some protection was afforded by Albert I, who in 1298 endeavored to suppress the riots and imposed a fine on the town of St. Poelten. However, in 1306, he punished the Jews in *Korneuburg on a charge of desecration of the *Host. *Frederick I (1308–30) canceled a debt owed by a nobleman to a Jewish moneylender, thus introducing the usage of the pernicious Toetbrief. He also prohibited Jews in his domains from manufacturing or selling clothes. Under *Albert II wholesale massacres of Jews followed the host libel in *Pulkau. A fixed Jewish tax is mentioned for the first time in 1320. Rudolph IV (1358–65), who unified all the legal codes then extant, retained the former enactments granting Jewish judicial autonomy, and took measures to prevent Jews from leaving Austria. The position of the Jews became increasingly precarious during the reigns of *Albert III and Leopold III. Cancellation of debts owed to Jews, confiscations of their property, and economic restrictions multiplied. In consequence, they became greatly impoverished. Their wretchedness culminated when *Albert V ordered the arrest of all the Jews after the host libel in Enns (1420); 270 Jews were burnt at the stake that year, a calamity remembered in Jewish annals as the *Wiener gesera. The rest were expelled and the property of the victims was confiscated. Austria became

notorious among Jewry as "Ereẓ ha-Damim" ("the bloodstained land"). Jewish settlement was subsequently renewed, and despite the persecutions, Austria became a center of spiritual leadership and learning for the Jews in southern Germany and Bohemia. The teachings of its sages and usages followed in its communities were accepted by Jews in many other countries. Austrian usage helped to determine the form of rabbinical ordination *(semikhah), mainly owing to the authority of R. *Meir b. Baruch ha-Levi. His colleague R. Abraham *Klausner compiled Sefer Minhagim, a Jewish custumal, which was widely used. During the reign of Ladislaus (1440–57), the Franciscan John of *Capistrano incited popular feelings against the Jews, leading to the expulsion of almost all of them from Austria proper. Under *Frederick III (1440–93) the position improved; with papal consent he gave protection to Jewish refugees and permitted them to settle in *Styria and *Carinthia. Yeshivot were again established, and under the direction of Israel *Isserlein, the yeshivah in Wiener Neustadt provided guidance for distant communities. Hostility to the Jews on the part of the Estates caused Emperor *Maximilian I (1493–1519) to expel the Jews from Styria and Carinthia in 1496, after receiving a promise from the Estates that they would reimburse him for the loss of his Jewish revenues. However, he permitted the exiles to settle in Marchegg, *Eisenstadt, and other towns then annexed from Hungary. A few Jews, including Meyer *Hirshel, to whom the emperor owed money, settled in Vienna. *Ferdinand I (1521–64) agreed only in part to requests by the Estates to expel the Jews, ordering their exclusion only from towns holding the "privilege" de non tolerandis Judaeis, i.e., the right to exclude Jews. Ferdinand employed a Jew in the mint. In 1536 a statute regulating the Jewish status (Judenordnung) was published, which included a clause enforcing the wearing of the yellow *badge on their garments. Counter-Reformation to 19th CenturyIn the period of the Counter-Reformation, during the reigns of Maximilian II (1564–76), *Rudolph II (1576–1612), and Matthias (1612–19), there were frequent expulsions and instances of oppression. Under Rudolph the Jewish population in Vienna increased; certain families enjoying special court privileges ("hofbefreite Juden") moved there and were permitted to build a synagogue. In 1621 *Ferdinand II allotted the Jews of Vienna a new quarter outside the city walls. In the rural areas the jurisdiction over the Jews and their exploitation for fiscal purposes increasingly passed to the local overlords. Important communities living under the protection of the local lordships existed in villages such as Achau, Bockfliess, Ebenfurth, Gobelsburg, Grafenwoerth, Langenlois, Marchegg, Spitz, Tribuswinkel, and Zwoelfaxing. In Vienna also, *Ferdinand III (1637–57) temporarily transferred Jewish affairs to the municipality. The *Chmielnicki massacres in Eastern Europe (1648–49) brought many Jewish refugees to Austria, among them important scholars. The situation of the Jews deteriorated under *Leopold I (1657–1705). In 1669 a commission for Jewish affairs was appointed, in which the expulsion of the Jews from Vienna and the whole of Austria was urged by Bishop Count Kollonch. In the summer of that year, 1,600 Jews from the poorer and middle classes had to leave Vienna within two weeks; and in 1670 the wealthy Jews followed. The edict of expulsion The Jewish policy of Maria Theresa (1740–80) wavered between the mercantilism which stood to gain from increased settlement of wealthy Jews and their participation in economic activities, and her own deeply ingrained enmity toward the Jews. A special decree was issued in 1749 encouraging Jews to found manufacturing establishments. The Judenordnung of 1753 regulated all aspects of Jewish public and private life, and was based on full judicial autonomy for the communities. At this time some Jewish financiers and industrialists, such as Nathan von *Arnstein, Lazar Auspitz, Bernhard *Eskeles, Israel *Hoenigsberg, and Abraham *Wetzlar, moved to Vienna, having the status of "Tolerierte" (tolerated) Jews. Some of them received titles for activities benefiting the Hapsburg Empire; many of their descendants left Judaism. The annexation of *Galicia in 1772 more than doubled the Jewish population of the monarchy, and inaugurated a continuous stream of migration from there, mainly to Vienna. From the end of the 18th century, with the growing centralization of the government of the empire and new political developments, the position of the Jews in Austria proper became increasingly linked with the history of the empire as a whole. As part of his endeavors to modernize the empire, *Joseph II (1780–90) attempted to make the Jews into useful citizens by introducing reforms of their social mores and economic practices and abolishing many of the measures regulating their autonomy and separatism. Although not altering the legal restrictions on Jewish residence (mainly affecting Vienna) or marriage, he abolished in 1781 the wearing of the yellow badge and the poll tax hitherto levied on Jews. Joseph II's Toleranzpatent, issued in 1782, in which he summarized his previous proposals, is the first enactment of its kind in Europe. Jews were directed to establish German-language elementary schools for their children, or if their number did not justify this, to send them to general schools. Jews were encouraged to engage in agriculture and ordered to discontinue the use of Hebrew and Yiddish for commercial or public purposes. It became official policy to facilitate Jewish contacts with general culture in order to hasten assimilation. Jews were permitted to engage in handicrafts and to attend schools and universities. Jewish judicial autonomy was abolished in 1784. Jews were also inducted into the army, which in due course became one of the careers where Jews in Austria enjoyed equal opportunities, at least in the lower commissioned ranks. The "tolerated" Jews in Vienna and the intellectuals who, influenced by the enlightenment movement (see *Haskalah), tended toward assimilation, accepted the Toleranzpatent enthusiastically. The majority, however, considered that it endangered their culture and way of life without giving them any real advantages. The implementation of these measures promoted the assimilation of increasingly broader social strata within Austrian Jewry. In 1792 the Jewish Hospital was founded in Vienna, which benefited Jews throughout the empire for many years. In 1803, there were 332 Jewish families living in Austria proper (including Vienna), and approximately 87,000 families throughout the Hapsburg Empire. 19th CenturyThe position of the Jews in Austria deteriorated after the death of Joseph II, though the Toleranzpatent remained in force. Francis I (1792–1835) introduced the Bolletten-tax (see *Taxation), and ordered that measures should be taken against "Jewish superstitions" and "vain rabbinical argumentation." Efforts to "enlighten" the Jews during his reign included the activities of Herz *Homberg, whose catechism "Benei Zion" was introduced into schools for the teaching of religion. Until 1856, Jews were compelled to pass an examination in it before they were permitted to marry. A decree issued in 1820 required all rabbis to study philosophy, and to use only the "language of the state" for public prayers; Jewish children were required to attend Christian schools. The period between the issue of the Toleranzpatent and 1848 saw further fundamental changes in Jewish life. A number of Jews were instrumental in the expansion and modernization of industry, transportation, commerce, and banking in the Hapsburg Empire. Lazar Auspitz, Michael *Biedermann, and Simon von *Laemel developed the textile industry; Salomon Mayer *Rothschild built the first railway; the Rothschilds, Arnstein-Eskeles, and *Koenigswarters were the outstanding bankers and were on the board of the newly founded National Bank. Many Jews had a university education and became prominent in journalism and German literature. Prominent among them were Moritz *Saphir, Ludwig August *Frankl, Moritz *Hartmann, and Leopold *Kompert. The less wealthy classes of Jews also prospered, opening workshops, or selling and peddling products of the developing industries. Their heightened awareness of human dignity evoked by their economic and cultural attainments and the relaxation of humiliating restrictions emphasized the basic inequality of their status, even among the wealthy and the nobility. It was even more bitterly resented on the background of Jewish emancipation in France, the liberalizing edict passed in Prussia in 1812, and the budding liberal, revolutionary, and nationalist ideologies in Europe. During the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), Nathan von Arnstein with other Jewish notables applied unsuccessfully to the emperor for the conferment of civil rights on Austrian Jewry. Joseph von *Wertheimer's anonymously published work on the status of Austrian Jewry (1842) advocated extensive reforms. In 1846 the humiliating *oath more Judaico was abolished. The number of Jews actively participating in the 1848 revolution, such as Adolf Fischhof, Joseph Goldmark, Ludwig August Frankl, Hermann *Jellinek (the brother of Adolf *Jellinek and later executed) – some of whom fell victims in the street fighting, among them Karl Heinrich *Spitzer – in part reflected the spread of assimilation among Jews who identified themselves with general political trends, and in part expressed the bitterness of those already assimilated. The new election law passed in 1848 imposed no limitation on the franchise and eligibility to elective offices. Five Jewish deputies, Fischhof and Goldmark from Vienna, Abraham Halpern of Stanislavov, Dov Berush *Meisels of Cracow, and Isaac Noah *Mannheimer of Copenhagen, were elected to the revolutionary parliament meeting at Kromeriz (Kremsier; 1848–49). On the other hand, the revolution resulted in anti-Jewish riots in many towns, and the newly-acquired freedom of the press produced venomous antisemitic newspapers and pamphlets (see Q. *Endlich, S. *Ebersberg, S. *Brunner). Isidor *Busch published his short-lived but important periodical Oesterreichisches Central-Organ fuer Glaubensfreiheit, Cultur, Geschichte und Literatur des Judenthums, in which Leopold Kompert was the first to advocate emigration as a solution of the Jewish problem in Austria (and initiated the Auf nach Amerika! ("Forward to America!") movement). After the revolution the specifically Jewish taxes were abolished by parliament. The imposed constitution ("Octroyierte Verfassung") of 1849 abrogated discrimination on the basis of religion. The hated Familiantengesetz became ineffective. Freedom of movement in the empire was granted. As a result old communities were dissolved and new ones emerged. Some Jews were admitted to state service. On Dec. 31, 1851, the imposed constitution was revoked. Although religious freedom was retained in principle, Jews were again required to obtain marriage licenses from the authorities, even if the number of marriages was no longer limited. The right of Jews to acquire real estate was suspended. Other restrictions were introduced up to 1860. In 1857 the establishment of new communities was prohibited in Lower Austria. Attempts were made to expel Jews from cities, based on the rights afforded by medieval charters. In 1860 a new, more liberal, legislation was promulgated, although in some parts of Austria Jews still were unable to hold real estate. In general, however, the position of the Jews was now improved. Jewish financiers in partnership with members of the nobility founded new industries and banks, outstanding among them the Creditanstalt. Jews founded leading newspapers and many became journalists. In 1862 Adolf *Jellinek, the successor of Isaac Noah Mannheimer, founded his modernized bet ha-midrash in Vienna. The new constitution of Austria-Hungary of Dec. 21, 1867, again abolished all discrimination on the basis of religion. The Vienna community then rapidly grew, attracting Jews from all parts of the monarchy. Jews increasingly entered professions hitherto barred to them and assimilation also increased. Communal organization remained, based on laws of 1789; in towns where there had not formerly been a Jewish community, only a "congregation for worship" (*Kultusverein) could be established. A law issued in 1890 authorized the existence of one undivided community in each locality, supervising all religious and charitable Jewish institutions in the area, and entitled to collect dues; only Austrian citizens were eligible for election to the communal board. In 1893 a rabbinical seminary, the *Israelitisch-Theologische Lehranstalt, was founded which also provided instruction for teachers of religion, and received aid from the authorities. The upper strata of Austrian Jewry identified themselves with German culture and liberal trends. This was reflected in the views of Jewish members in both houses of parliament such as Ignaz *Kuranda, Heinrich Jacques, Rudolph *Auspitz, Moritz von *Koenigswarter, and Anselm von *Rothschild. The German Schulverein (Association for German minority schools) supported Jewish schools in non-German towns. ANTISEMITISMToward the latter part of the 19th century, antisemitism rapidly developed in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the blood libel case of *Tisza-Eszlar being followed by rioting and other false accusations. Antisemitism manifested two tendencies. The Catholic-religious form later found expression through Karl *Lueger and his *Christian-Social party; and in its pan-Germanic nationalistic form it was expressed by Georg von *Schoenerer and his party (see *antisemitic political parties). The government, however, opposed antisemitic propaganda. The manifestation of antisemitism brought a change in ideological attitude on the part of the Jews, strengthening the national elements. Efforts were made to combat antisemitism in Austro-Hungary by Joseph Samuel *Bloch with the help of his weekly Oesterreichische Wochenschrift (founded 1884) and the Oesterreichisch-Israelitische Union (later *Union Oesterreichischer Juden), founded in 1885. An association to combat antisemitism ("Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus"), consisting of members of the higher strata of Austrian society, was founded in 1891 under the presidency of Arthur Gundaccar Freiherr von Suttner (1850–1902). The historian Heinrich *Friedjung continued to urge complete Jewish integration into the German nation. Some Jews ascribed the wave of anti-Jewish hostility to the immigration at this period of masses of "uncultured" Jews from Eastern Europe. In opposition to the assimilationist Oesterreichisch-Israelitische Union a Juedisch-politischer Verein (later Juedisch-nationale Partei) advocated an independent Jewish policy. Jewish nationalist ideology penetrated Austrian circles through the influence of Perez *Smolenskin, Leon *Pinsker, and Nathan *Birnbaum. The first Jewish national students' society, *Kadimah, was founded in Vienna in 1882. ZIONISMVienna was the city of Theodor *Herzl, and the Zionists combined to strengthen the Jewish national viewpoint During the war, 36,000 Jewish refugees arrived in Vienna from Galicia and Bukovina alone. The *Zentralstelle fuer juedische Kriegsfluechtlinge was formed to provide them with social assistance. The Zionist social worker and politician Anitta Mueller Cohen founded numerous social institutions to support the refugees. Many stayed on after the war and influenced the revival of Jewish culture and life in hitherto stagnant communities. In 1918 there were 300,000 Jews in 33 communities in the Austrian Republic, with 200,000 Jews living in Vienna in 1919. Distribution of the communities was as follows: ten in Burgenland, one in Carinthia, sixteen in Lower Austria, one in Salzburg, one in Styria, one in Tyrol, two in Upper Austria, one in Vorarlberg. (See Table: Jews in Austrian Provinces.)

After 1918JEWISH RIGHTS AND POLITICAL ACTIVITYThe Treaty of St. Germain (1919) guaranteed the Jews *minority rights. The Zionists founded a Jewish National Council (Juedischer Nationalrat). On November 5 they forced Alfred Stern, a former city councillor and the assimilationist president of the Jewish community since 1903, to resign. Stern died on December 1 at age 88. His successor became in 1920 the Generaloberstabsarzt (senior medical officer of the Austrian-Hungarian army) Alois Pick, who remained in office until 1932. A Jewish militia (Juedische Stadtschutzwache) was founded and protected Jews in the postwar unrests. The Zionist Robert *Stricker was elected to the first Austrian National Assembly in February 1919. In October 1920, due to a change of the election law, he was not reelected. Besides his political involvement as board member and later vice president of the Jewish community Stricker also edited the Juedische Zeitung, the daily the Wiener Morgenzeitung, and the Neue Welt. Three Zionists (Jakob Ehrlich, Bruno Pollack-Parnau, and Leopold Plaschkes) were also elected to the Vienna city parliament. Jews who had settled in Austria after the outbreak of the war were deprived of the right to vote, and the reorganization of the Vienna electoral districts also adversely affected the Jewish voting strength. Special measures disqualifying the war refugees from becoming Austrian citizens were introduced in 1921. In the postwar era, many Zionist youths intending to immigrate to Ereẓ Israel passed through Austria. In 1919 therefore the first Palaestinaamt (Palestine Office) was founded in Vienna, directed by Emil Stein and Egon Michael Zweig. Among Jews, chiefly in Vienna, the Social-Democratic Party gained many supporters, attracting the lower-middle-class electorate. Some of its leaders of Jewish descent, such as Otto *Bauer and Julius Deutsch, were widely popular; in Jewish affairs they adhered to a policy of assimilation. Their leading positions, however, drew antisemitic invective. The Social Democrats were careful to avoid the label of a Jewish party and the display of too many Jews in prominent positions. In the period 1919–1939, a number of Jewish educational institutions opened their doors to students. These included the Jewish Realgymnasium (since 1927 named Chajesgymnasium), the Paedagogium (a Hebrew teachers' seminary), and a seminary for religion teachers. The Jewish community maintained a museum – the oldest Jewish museum worldwide, opened in 1896 – a famous library, which was directed by the historian Bernhard Wachstein, and a renowned historical commission. In 1927 Chief Rabbi Chajes died; he was succeeded in 1932 by David Feuchtwang, who also was the honorary head of the Vienna Mizrachi. After Feuchtwang's death in 1936 the scholar Israel Taglicht became chief rabbi. In addition, youth movements had many supporters. Reforms were introduced in communal institutions and new ones were established. These included the Organisation fuer juedische Wanderfuersorge ("Organization for the Care of Jewish Migration"), established in 1930 to cope with the huge transitory Jewish migration, which became even greater with the influx of emigrants from Germany after 1933. From 1932 until 1938 the Zionists formed the majority in the executive of the Vienna Jewish community. After the suppression of the Social Democrats in 1934, the Jewish situation declined, mainly through an insidious discrimination. Jews were quietly deprived of their means of existence under various pretexts while the authorities continued to emphasize that all citizens had equal civic status. In schools Jewish and non Jewish pupils were segregated. Jews were permitted to join the Vaterlaendische Front which in 1934 replaced the political parties. In January 1938 it was proposed that Jewish youth should be organized in a separate subdivision of the youth division of the Front. This the Zionists accepted willingly, but it angered those in favor of assimilation. The Christlich-Soziale Partei (*Christian Social Party), which formed the majority of the governments in Austria, under Ignaz Seipel, Engelbert *Dollfuss, and Kurt von Schuschnigg, was not racist antisemitic; the dependence of Austria on the League of Nations and the Western powers, and the growing menace of National Socialism, made the government play down antisemitism and seek Jewish support. Federal Chancellor Schuschnigg sent Desider *Friedmann, the president of the Vienna community from 1932 until 1938, on a mission abroad to mobilize support for the Austrian currency. There was a wide discrepancy between the attitude of the government and of the Austrian public toward the Jews. When, for instance, Schuschnigg congratulated Sigmund *Freud on his birthday in 1936, the letter was not published in the press. On the other hand, the official policy to emphasize everything specifically Austrian enhanced the reputation of writers and intellectuals of Jewish origin living there. Outstanding were the writers Franz *Werfel, Stefan *Zweig, Arthur Schnitzler, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Felix *Salten, Hermann Broch, Peter *Altenberg, and Alfred *Polgar, the musicians Bruno *Walter and Arnold *Schoenberg, and the theatrical producer Max *Reinhardt. In 1932 the Austrian association of Jewish frontline fighters (Bund Juedischer Frontsoldaten Österreichs) was founded. It was headed by Major-General Emil von *Sommer and later by Captain Sigmund Edler von Friedmann and had about 20,000 members. Efforts to combat antisemitism, including reminders of the part played by Jewish soldiers in World War I, could do nothing to counter the violent hatred against the Jews ingrained in wide sectors of the Austrian population. Many Jews, outstanding among them Emil von Sommer – who founded in 1934 the monarchist association of Jewish frontline fighters (Legitimistische Jüdische Frontkämpfer) – yearning for Hapsburg rule, became monarchists. [Nathan Michael Gelber and Meir Lamed / Evelyn Adunka (2nd ed.)] The Holocaust1938–1939. The liquidation of Austrian Jewry began with the Anschluss (annexation) to Germany on March 13, 1938. According to the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde, the Jewish community of Vienna, there were at the time 181,778 Jews in Austria, of whom 91.3% (165,946) were living in Vienna. According to Himmler's statistics, however, the number of Austrian Jews persecuted under the *Nuremberg Laws reached 220,000; in addition, tens of thousands of persons of Jewish descent were affected by the racial laws. The new Nazi regime immediately introduced decrees and perpetrated acts of violence of an even greater scope and cruelty than those then practiced in the Reich itself. The Jews were denied basic civil rights, and they and their property were at the mercy of organized and semi-organized Nazi gangs. The activities of Jewish organizations and congregations were forbidden. Many Jewish leaders were imprisoned, and several were murdered in *Dachau concentration camp. A fine of 800,000 schillings ($30,800) was levied on the Jewish communities. At the same time, the first pogroms took place in Vienna and in the provinces, and synagogues, including the Great Synagogue of Vienna, were desecrated and occupied by the German Army. The main victims of systematic terrorization were the Austrian Jewish intelligentsia and property owners. The former were immediately banned from any public activity, from educational and scientific institutions and from the arts. Many of them – including Sigmund Freud, Stefan Zweig, and Hermann *Broch – were among the first Austrian Jewish refugees. Freud left for London by plane but before he left he gathered his disciples, pioneers of psychoanalysis, and invoked the memory of Rabban *Johanan ben Zakkai, who after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem made the Torah portable. The biggest property owners were arrested by the Gestapo and forced to turn over their property, most especially their artworks. Some of those who refused were murdered and many others were sent to Dachau, where they were either killed or committed suicide. In addition, street attacks and brutal persecution became daily occurrences in the lives of Austrian Jews of all social classes. The dramatic change in circumstances led to great despair among Austrian Jews. In March alone, 311 cases of suicide were registered in the Viennese community, and in April, 267. During these two months, at least 4,700 Jews escaped from Austria. Systematic deportation of Jews and the confiscation of their property began in several Austrian provinces. The ancient Jewish communities of *Burgenland were deported over the Czech border. A group of 51, which was returned to Austria, was sent up and down the Danube for four months and denied entry to all the countries bordering on the river. As a result of the persecutions, a stream of Jews from the provinces, most of them destitute, began to flow to Vienna. In May 1938 the Viennese Jewish community renewed its activities and several of its leaders were released from prison in order to help organize mass emigration which the Nazi authorities encouraged. The Zionist Palestine Office in Vienna was permitted to organize both legal and "illegal" immigration to Palestine. In the same month, the Nuremberg Laws were officially enforced in Austria. In August 1938, under *Eichmann's aegis, the "Zentralstelle fuer juedische Auswanderung" was established in Vienna, headquartered in a confiscated Rothschild palace. This organization was to be responsible for the "solution of the Jewish problem" in Austria. Its "efficient" methods of persecution and deportation were later copied in Germany and in several of the German-occupied countries. A special body, the Vermoegensverkehrsstelle, was responsible for the transfer of Jewish property to non-Jews. With the help of the major Jewish welfare organizations in the world, the community and the Palestine Office were able to assist in the emigration of thousands of Jews. The importance of this aid grew with the straitened circumstances of Austrian Jewry; as against 25% of the emigrants who needed financial assistance in May and July 1938, 70% needed assistance in July and August 1939. Between July and September 1938 emigration reached a monthly average of 8,600. Hundreds of training courses were organized to prepare emigrants for new occupations in the countries of immigration. 1940–1945. Between February and March 1941, desperate attempts to continue limited emigration resulted in the deportation of 5,000 Jews to five places in the *Lublin district. It is assumed that all met their death within the year, being murdered either locally or in the gas chambers of *Belzec. From October to the beginning of November, another 5,486 Jews were deported to the *Lodz Ghetto. After the official prohibition on emigration, there remained approximately 40,000 Austrian Jews. Very few could leave the country after this date. Of the 128,500 who had emigrated up to that time, 30,800 had gone to England, 24,600 to other European countries, 28,600 to the United States, 9,200 to Palestine, and 39,300 to 54 other countries. At the end of 1941, with the Nazi occupation of territories in the Soviet Union, 3,000 Austrian Jews were deported to the ghettos of Riga, Minsk, and Kovno; many were put to death upon arrival in the vicinity of these ghettos. After the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann announced to the Viennese community his general Aussiedlung ("evacuation") program under which 3,200 more Austrian Jews were deported to Riga, 8,500 to Minsk, and 6,000 to Izbica and several other places in the Lublin region. This last group was almost entirely exterminated. Between June and October, 13,900 people were deported to *Theresienstadt, most of them aged 65 and over. On Oct. 10, 1942, the last transport of 1,300 persons left for Theresienstadt. There still remained 7,000 Jews in Austria (about 8,000 according to the Nuremberg Laws). The majority were spared because they were married to non-Jews. All able-bodied persons were compelled to do forced labor. On November 1, 1942, the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde was dissolved Loewenherz's deputy was the former community rabbi and lecturer at the Israelitisch-theologische Lehranstalt Benjamin Murmelstein. In January 1943 he was deported to the ghetto Theresienstadt. In December 1944 he became the "Judenaelteste" (Elder of the Jews) of Theresienstadt after Jakob Edelstein and Paul Eppstein. In June 1945 Murmelstein was arrested by the Soviet authorities. He was imprisoned in Leitmeritz and accused of collaboration with the Nazis. After 18 months the Czechoslovak prosecutor released him for lack of evidence. Murmelstein later went to Italy; he lived in Rome as a businessman and private scholar, researching in the Vatican library, until his death in 1989. Isolated deportation continued from January 1943 until March 1945, and consisted of not more than a hundred persons in each transport. At least 216 Jews were sent to *Auschwitz and 1,302 Jews to Theresienstadt. Most of the victims were former communal workers, and Jews whose non-Jewish spouses had died. In the summer of 1943, there were still approximately 800 Jews left in Vienna. They had gone underground and were secretly helped by members of the community and the Budapest Jewish rescue committee (Va'adat ha-Haẓẓalah). A few managed to escape to Hungary, but many others were caught by the Gestapo and sent to Auschwitz. Some managed to stay underground until Vienna fell to the Soviet Army. In July and December 1944, approximately 60,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Vienna and Lower Austria, to be employed by the Nazis in building fortifications. A few were permitted to receive treatment at the Vienna Jewish hospital. Just before Vienna was liberated, 1,150 were deported to Theresienstadt. During the last months of the war, thousands of Jewish evacuees from various concentration camps crossed Austria. A few remained in Vienna and the Vienna district or were transferred to Austrian camps. The remnant of the Viennese Jewish community organized itself into a committee to save the victims, and extended help to them in conjunction with the International Red Cross and Jewish welfare organizations. A report by the Red Cross representative described the last synagogue in the Third Reich located in the cellar of the Viennese Jewish hospital. Of the approximately 50,000 Jews deported from Austria to ghettos and extermination camps only 1,747 returned to Austria at the end of the war. (The largest group of survivors, which numbered 1,293, was liberated from the Theresienstadt Ghetto.) Among the Austrian victims of the Holocaust there were over 20,000 Austrian Jews who had migrated to other European countries later conquered by the Nazis. The number of Austrian Jewish victims of the Holocaust is estimated at 65,000. One of the largest and most terrible of concentration camps, *Mauthausen, where thousands of European Jews met their death, was situated in Austria. A large part in the campaigns to exterminate European Jewry was played by Austrian Nazis, including Eichmann, *Globocnik, *Kaltenbrunner and Hitler himself. In 1946, a documentation committee (Juedisch historische Dokumentation) was set up in Vienna by Tuvia Friedman for the tracing and prosecution of Nazi war criminals. [Dov Kulka] Early Postwar PeriodAt the end of World War II, there were many displaced persons in Austria, most of them from Hungary. They had been sent to Austrian concentration camps during the last two years of the war. Their number was then estimated at about 20,000. Though some returned to their countries of origin after the liberation, postwar Austria had one of the largest concentrations of still unsettled Jewish displaced persons. It was the main transit country for Jewish refugees from Poland, Hungary, Romania, and other East European countries, on their way to Palestine or to the main concentration of refugees in the American Zone of Germany. The number of displaced persons reached its peak in late 1946, when it was estimated at 42,500, of whom over 35,000 were in the American-occupied area of Austria, i.e., in the western part of the country. The most important and biggest displaced persons' camp in Vienna was the "Rothschildspital," the former hospital of the Jewish community, which was later sold and demolished in 1960. Head of the committee of former concentration camp prisoners and Jewish refugees was Bronislaw Teichholz. The number of the refugees later dropped, particularly as a result of mass emigration following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. By 1953 only 949 refugees were left in displaced persons camps. In May 1945 Josef Loewenherz was arrested by the Soviet occupation authorities and taken to Czechoslovakia. After several weeks he was released. With the help of his family he immigrated via London to the United States, where he died in 1960. The same as Murmelstein, he never came to Vienna again. The secretary of state of the new Austrian government, who was responsible for the Jewish community, the prominent Communist writer Ernst Fischer, appointed in summer 1945 the 75-year-old well known physician Dr. Heinrich Schur, who had survived, because he was married to a non-Jewess, as the first provisional chairman of the Jewish community. After complaints about Schur's age and inability to cope with the many problems of the community Fischer appointed in September 1945 as Schur's successor the Communist journalist David Brill, who had worked as a journalist and private secretary of the chairman of the Communist party in Austria, Johann Koplenig. Brill organized, together with other party In 1946 the community celebrated the 120-year-jubilee of the only surviving synagogue, the famous Stadttempel in the Seitenstettengasse, which was built in the backyard of other houses, because of the Austrian law in the 19th century. Nevertheless provisional benches could only be erected in 1947. The temple could be restored to its former glory only in 1963. It took some three years, until 1948, until a new chief rabbi, Akiba Eisenberg, the former rabbi of the city of Györ in Hungary, could be found for the spiritually deserted Jewish community. Eisenberg was a very outspoken person and a strong Zionist. He remained chief rabbi until his death in 1983. After the second elections for the community executive in 1948, in which several parties stood for election, the blind lawyer David Schapira, a survivor of Theresienstadt and devoted Labour Zionist (of the Poale Zion), became president. He was the head of the so-called Jewish Federation and was strongly supported by Ernest Stiassny, the director of the Vienna office of the World Jewish Congress, who founded an association of Austrian Jews as a counter-institution against the then Communist-led Jewish community. During Schapira's term of office, in August 1949, the remains of Theodor Herzl were transferred to the State of Israel according to his last will. The ceremony and the surrounding festivities were the biggest and most impressive demonstration of the existence and will to survive of the Viennese Jewish community after the Shoah. The State of Israel sent the then 78-year-old Isidor Schalit, once a close collaborator of Herzl and a member of the famous student union Kadimah, to Vienna. The various Zionist associations organized 14 events. This was only one example of the many activities of the Zionist movement (that included the always quarreling Zionist Federation, the Landesverband, the Poale Zion, the General Zionists, the Revisionists, the Mizrachi, the WIZO, and the youth organizations) until the late 1960s. They organized many lectures and courses as well as convening large conferences three times. The Zionist Federation was strongly supported by the two emissaries S.J. Kreutner and Aron Zwergbaum from the Organization Department of the World Zionist Organization in Jerusalem. Their aim was not only aliyah, but also education, fostering of Jewish identity, and a democratic takeover of the Jewish community executive, at which they were no longer successful after 1952. A Hebrew school, which was supported by the Zionists, had to close down in 1967 because of lack of pupils and funding. The culmination of the community's support of Israel was reached when after Israel's Six-Day War, in a financially strained situation, the Jewish community sent a check of ATS 10 million to Israel with the help of a bank credit. After two short and turbulent presidencies of the General Zionist Wolf Hertzberg and the Communist Kurt Heitler, both of them lawyers, there began in 1952 the long era of the rule of the Social Democratic party Bund werktaetiger Juden (Union of Working Jews). They stood for an assimilationist and strongly anti-Communist policy. Their first president was the lawyer Emil Maurer, who had been governor (Bezirksvorsteher) of the seventh district of Vienna until 1934, had been imprisoned in the concentration camps Dachau and Buchenwald in 1938, and had immigrated to Britain in 1939. Although Maurer was on good terms with several prominent Socialist Austrian politicians, the Jewish community did not succeed in achieving a satisfying result for the restitution of property. Maurer's successor in 1963 was Ernst Feldsberg, a bank official and survivor of Theresienstadt. In the 1930s he had been a board member of the Union Oesterreichischer Juden and a member of the executive of the Jewish community. Feldsberg was undoubtedly the most active functionary of the Jewish community in many of its bodies both before and after the Shoah. In the 1960s the building of a community center failed because of lack of funding, although the cornerstone was laid in a public ceremony in the presence of prominent politicians. Community plans to erect a Jewish museum, for which a provisional room was opened in 1964 and closed a few years later, and to reorganize and open the library, failed. In 1966 the Jewish community opened a youth center. In 1967 the ceremonial hall in the main Jewish cemetery was built. In June 1975 the cornerstone was laid for a monument to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust at the site of the former concentration camp of Mauthausen. The Jewish community published from 1958 the monthly Die Gemeinde. The Association of Jewish Students began, in 1952, to publish an outstanding cultural journal, Das Juedische Echo, which continued as an annual. Among its founders was Leon Zelman, who from 1978 was the director of the Jewish Welcome Service. The General Zionists published Die Stimme (from 1947 until 1963), the revisionist Zionists publish Heruth (1957– ) and Die Neue Welt und Judenstaat (from 1948 until 1952). It was continued as a cultural Jewish journal under the name Die Neue Welt and from 1974 it has appeared as Illustrierte Neue Welt, edited by Joanna Nittenberg. In 1967 Desider Stern of the Vienna B'nai B'rith lodge Zwi Perez Chajes organized an exhibition of 400 books by German Jewish authors and published an expanded catalogue in 1970 with 700 entries, which became one of the most important In 1961 Simon *Wiesenthal settled in Vienna. As in Linz he directed the documentation center for Nazi criminals, first as an official of the association of Austrian Jewish communities. After a conflict with the executive director of the Vienna Jewish community Wilhelm Krell he left this position and founded the "Bund juedischer Verfolgter des Naziregimes" (Union of the Jewish Persecuted of the Nazi Regime). The Bund also stood for the elections to the board of the Jewish community, tried in vain to break the majority, and published in its journal – Der Ausweg (The Way Out) – numerous reports about its defects and its cold, bureaucratic character. Feldsberg's successor was the lawyer Anton Pick. In the interwar years he was a functionary of the Socialist Democratic Party, close to their leader Otto Bauer, and had spent time in Palestine, where he published articles in Davar. In 1976 younger members of the community founded a new party, called the "Alternative." Their aim was the renewal of the Jewish community and their most important reproach concerned the selling of a great deal of real estate at cheap prices to the city of Vienna, which began in the 1960s and which the opposition, the group of Simon Wiesenthal and the Zionists, polemically called the "second Aryanization." They and a second list, called the "Young Generation" (Junge Generation), eventually gained the majority of the community board and produced the next two presidents, the lawyer Ivan Hacker from 1981 until 1987 and the furrier Paul Grosz. The number of Jews living in Austrian communities rose with the return of several thousand Jews from camps in Eastern Europe, from the countries to which they had fled (mainly Great Britain, China, and Palestine), and from their hiding places. A small percentage of displaced persons settled in Austrian towns. The number of Jews in these communities reached a peak in 1950 with 13,396 registered. As in the past, the large majority lived in Vienna (12,450), and the rest in the capitals of the provinces (Laender) of Graz, Linz, Salzburg, and Innsbruck. From 1950 their number began to decrease. In 1965, 9,537 persons were registered as members of the community, of whom 8,930 lived in Vienna. It is estimated that another 2,000 Jews, not registered as community members, lived in the country. Thereafter the number of Jews remained more or less stable, with a slight tendency to fall. The ancient communities of Burgenland, on the Austro-Hungarian border, which before the Anschluss had numbered about 4,000 persons, were not rebuilt. In 1968 nearly 65% of Austrian Jewry was aged 50 and over. Austria became a country of transit for the Jewish migration from Eastern Europe to Israel and the West. In general, these travelers spent only a few days in Austria, in camps in and around Vienna. However, after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, about 20,000 Jewish refugees fled to Austria. Most continued on their way after a short while, between 200 and 300 remaining in Austria. ANTISEMITISMThe tradition of antisemitism was not uprooted in Austria, nor confined to ex-Nazis or neo-Nazis, who found sanctuary in the Freiheit (Freedom) Party. Only a few months after the end of World War II, a leader of the large Christian Party (the People's Party), Leopold Kunschak, declared that he had always been antisemitic. This did not prevent his being elected president of Parliament. The universities were often the scene of antisemitic demonstrations. There was the case of the Austrian university professor Taras Borodajkewycz, who boasted about his Nazi past and made vicious antisemitic remarks during his lectures. A demonstration with about 6,000 students against and 1,000 for him escalated into a street riot. In the course of it an elderly demonstrator was mortally beaten by a neo-Nazi student, who was later sentenced to ten months' imprisonment. Borodajkewycz was suspended on most of his pay. The official attitude toward Nazi criminals, when brought to trial, was generally lenient; among the cases that aroused international indignation was the acquittal of the brothers Johann and Wilhelm Mauer, accused of mass murder in the Stanislaw Ghetto. Public pressure caused their retrial and sentence. In 1964 Franz Murer, who was responsible for the murder of the Jews of Vilna, was acquitted. Although the Austrian Supreme Court quashed this verdict, Murer was not tried again. There was an antisemitic campaign against Bruno *Kreisky, leader of the Social Democratic Party, of Jewish origin, who served for several years as foreign minister. After an election victory in 1970 Kreisky became federal chancellor (prime minister), the first Jew to hold this high office. Kreisky's governments from 1970 until 1983 included six former Nazis, for which he was publicly attacked by Simon Wiesenthal. In the 1970s Bruno Kreisky made libelous vicious lying attacks on Wiesenthal. The Kreisky-Wiesenthal affair was followed by a series of court actions, in which Kreisky and the Austrian journalist Peter Michael Lingens, who attacked the chancellor, were eventually found guilty. Only in the 1990s did the climate change and many official Austrian honors bestowed on Wiesenthal. Negotiations between the executive committee for Jewish claims on Austria, headed by Nahum *Goldmann, and the Austrian government started in 1953, but the process of legislation on the return of property and the payment of indemnification to victims of Nazi persecution was concluded only in 1962 and was considered inadequate. No satisfactory progress was made with regard to the solution of problems stemming from the Nazi period. Legislation on indemnification to victims of Nazi persecution did not satisfy the most elementary demands and could not compare with that of West Germany. On the other hand, Austria showed a humanitarian approach in granting transit facilities or temporary residence for Jews and as a result played a major role in enabling Soviet Jews to leave the country when they received permission to immigrate to Israel. They were first housed in Schoenau Castle, but it was closed as a result of a terrorist attack in September [Chaim Yahil / Evelyn Adunka (2nd ed.)] The 1980sIt was estimated that no less than 90% of the Jews of Austria resided in Vienna at the end of the 1970s, the remainder being in small communities in Salzburg, Linz, and Graz. Some 7,500 Jews were registered members of the Jewish community of Vienna, and it was estimated that there were between 3,000 and 4,000 who were not registered. More than two-thirds of the community was over the age of 60 and the major share of the communal budget was expended on aid to the aged, of whom nearly 1,000 were supported from communal funds. On August 29, 1981, Arab terrorists attacked the Seitenstettengasse synagogue in Vienna, killing two and wounding 18. Police who were guarding the synagogue apprehended the perpetrators (police guards had been on duty at the synagogue from 1979 when an Arab terrorist group claimed it was responsible for causing an explosion on the synagogue grounds). In 1985 the first conference of the World Jewish Congress in Vienna was overshadowed by the populist Freedom Party's defense minister's act of sending his official helicopter to pick up the Nazi war criminal Walter Reder when he was released from an Italian prison. (He had slaughtered 1,500 Italian civilians.) The year 1986 was dominated by the election of President Kurt Waldheim – the most important event of the 1980s for the Austrian state and the Jewish community, causing a most serious crisis for both. The World Jewish Congress charged Waldheim with wartime involvement in Nazi activities in the Balkans as a staff member of General Löhr, who was executed as a war criminal by the Yugoslavs in 1947. During Waldheim's election campaign strong antisemitic feelings were openly expressed by parts of the population, and also by several politicians and the media, especially by the two dailies, Die Presse and Die Neue Kronen Zeitung. The latter, which had a circulation of 1.5 million in a country of 7 million, had already published in 1974 a notorious series about the Jews by Viktor Reimann which was strongly attacked as antisemitic and discontinued. Waldheim's election was opposed by many intellectuals and artists, who formed a new club called "New Austria" and organized demonstrations, symposia, vigils, press conferences, and publications in order to recall Austria's responsibility for the Nazi crimes. Many Jews considered emigrating and felt homeless again. Israel recalled its ambassador and replaced him by a chargé d'affaires. The coolness between the two countries lasted until Waldheim left the presidency in 1992. Because of the Waldheim affair the so-called "Bedenkjahr" (year of commemoration), which in 1988 marked the 50th anniversary of the "Anschluss" of Austria to Nazi Germany, was taken very seriously. At the state ceremony and the festive event in Parliament on March 11 the leading role was played by the socialist Austrian chancellor Franz Vranitzky. Whole series of symposia, exhibitions, lectures, discussion groups, etc., were organized, especially at universities and schools (including many events fostering Christian-Jewish dialogue). This was a new experience for Austria, at last confronting historic truth. In June 1988 the heads of the Austrian Jewish community, Chief Rabbi Chaim Eisenberg and President Paul Grosz, were received by Pope John Paul II during his visit to Vienna. In July Helmut Zilk, the mayor of Vienna, commissioned from the sculptor Alfred Hrdlicka a monument to commemorate "the victims of war and fascism" in the center of Vienna. It shows a kneeling Jew being forced by the Nazis to clean the streets in 1938. This caused great controversy in the Jewish community because of the Jew's humiliating posture. In June 1987 the deputy mayor of Linz, Carl Hoedl, wrote an open letter to Edgar *Bronfman, head of the *World Jewish Congress, comparing his attitude to Waldheim with the "show trial of the Jews about Jesus." In November of that year Michael Graff, the general secretary of the People's Party, resigned after saying: "As long as there is no proof that Waldheim strangled six Jews with his own hands, there will be no problem"; however, he remained active in politics. COMMUNAL AND CULTURAL LIFEIn September 1981, the Austrian Constitutional Law amended the Israelitengesetz of 1890 after an application by Benjamin Schreiber, the head of the Vienna Agudah. The amendment allowed more than one Kultusgemeinde in any geographic region. In 1982 the Austrian Jewish museum in Eisenstadt near Vienna – the first in Austria – was opened. It was initiated by Kurt Schubert, the founder of the institute of Jewish studies of the University of Vienna. Its director is Johannes Reiss. In 1983 the late Chief Rabbi Akiba Eisenberg was succeeded by his son Chaim Eisenberg, who was still serving in 2005. In 1988 he was appointed chief rabbi of Austria, a title which did not exist before the Holocaust. In 1984 a series of events called "Versunkene Welt" on the lost culture of Eastern Jewry was organized by Leon Zelman's Jewish Welcome Service. In 1984 the Art Nouveau Synagogue in St. Poelten was renovated and in its building was established a new Institute for the History of the Jews of Austria. It was directed until 2004 by Klaus Lohrmann; his successor was Martha Keil. In 1983 the city of Vienna began inviting former Jewish citizens to visit their old home for a week. Organized by the Jewish Welcome Service, headed by Leon Zelman, several thousand Viennese Jews returned to Vienna in the framework of the program. Several new institutions were built or founded, among others the Jewish community center in 1980, the Jewish High In 1988 the home for the care of the aged was enlarged and named after Maimonides (Maimonides Zentrum). The historic Stadttempel, the main synagogue of Vienna, was reopened after its renovation in the presence of Chancellor Vranitzky, who in 1989 received the gold medal of the Austrian Zwi Perez Chajes B'nai B'rith lodge. In 1988 the Vienna yeshivah was founded; it included a boarding school and was praised in 1991 by the well-known former Viennese rabbi Schmuel (Schmelke) Pinter from London in the highest terms. In 1989 the Jewish Institute of Adult Education was founded by Kurt Rosenkranz. It also organized guest performances of Yiddish theater groups from Tel Aviv, Montreal, and Bucharest. After ten years, in 1998, it published a Festschrift. The 1990s and AfterFrom 1990 a Liberal Jewish congregation called Or Chadasch functioned in Vienna. Its president from the beginning through the year 2005 was the dermatologist Theodor Much. It had many visiting and some permanent rabbis; amongst the latter were Michael Koenig, Walter Rothschild, Robert L. Lehmann, Eveline Goodman-Thau, and in 2004/5 Irit Shillor. In February 2004 it opened its own synagogue and community center, with the financial help of the city of Vienna and the Austrian government, in rent-free premises belonging to the Jewish community. In 1992 President Klestil opened the Sephardi Center with two synagogues, a Bukharian and a Georgian one. In March 1993 the newly built synagogue of Innsbruck – which had about 40 members – was consecrated. In June 1993 the Vienna Jewish community organized a large-scale commemoration of Aaron Menczer, the charismatic leader of Viennese Youth Aliyah, who was murdered in 1943 in Auschwitz. His surviving pupils unveiled a large memorial to Menczer in the foyer of the Stadttempel. After the retirement of Chief Cantor Abraham Adler in 1993 the Jewish community took on Israeli-born Shmuel Barzilai, another first-rate chief cantor. In September 1994, the Vienna Jewish community opened the Esra psychological and social case center, an outpatient center particularly for people suffering from the so-called Holocaust syndrome. In 2004 it celebrated its first ten years of existence with a main speech given by the new Social-Democrat Austrian president Heinz Fischer and publication of a Festschrift. In June 1991 Vranitzky made a speech in Parliament, in which he fully acknowledged Austria's moral guilt and responsibility for the Nazi crimes – the first such speech by the head of an Austrian government. In 1993 an Austrian Gedenkdienst was founded, which gave young Austrians the opportunity to work at Holocaust memorial sites instead of doing compulsory military or civilian service. Up to 2002 about 150 young men and some women had worked in the framework of this service in 15 countries. In 2001 the Archive for the Austrian Resistance (Dokumentationsarchiv des oesterreichischen Widerstands) finished a project to document the Austrian victims of the Holocaust. The names and data of 62,000 victims were published on their website and on a CD-ROM. In 1998 the Austrian Parliament decided to inaugurate a commemoration day for the victims of racism and violence. The day is commemorated around May 5, the day of the liberation of the Austrian concentration camp Mauthausen. The real estate tycoon Ariel Muzicant initiated the Austrian Historical Commission of the Republic of Austria. It was founded in 1998, headed by the distinguished judge and head of the Administrative Court Clemens Jabloner, and operated until 2003. In 47 projects, 160 historians were asked "to investigate and report on the whole complex of expropriation in Austria during the Nazi regime and on restitution and/or compensation (including other financial or social benefits) after 1945 by the Republic of Austria." All the reports were published by the German publisher Oldenbourg. In several official statements the Austrian Republic promised – at last – to pay adequate compensation to the surviving Austrian victims of National Socialism. In summer 1995 a National Fund was established by the Austrian Parliament, which was endowed with 500 million ATS. It was directed by Hannah Lessing and paid about 20,000 Austrian victims of National Socialism 70,000 ATS as individual compensation and 80,000 ATS for stolen property and apartments. In 1996 more than 600 art objects, whose owners could not be identified, were at last paid for by the Republic of Austria to the Jewish community. They were sold at the internationally acclaimed Mauerbach auction by Christie's (named for the former monastery where they were hidden). The proceeds of 155 million ATS were given to Jewish and some non-Jewish Holocaust victims. In April 1998 Ariel Muzicant was elected president of the Vienna Jewish community. He was the first president born after the Holocaust. In 2002 he was reelected. In November 1998 the synagogue of Vienna's Josefstadt district in the Neudeggergasse was reproduced in full size for six weeks in commemoration of the pogrom in November 1938. Former Jewish residents of the district were invited, a book was published, and a film was made by the Austrian filmmaker Käthe Kratz. In June 1999 the Vienna Jewish community celebrated the 150th anniversary of its existence with a gathering of 1,300 people in the Vienna Burgtheater. In October 2000 a monument to the Austrian victims of the Shoah, showing a stylized library of untitled books in a 70-sq.-m. space, designed by the British artist Rachel In November 2000 the newly built synagogue of Graz, the second largest city of Austria, was consecrated. The square in front of the synagogue was named after Chief Rabbi David Herzog. The Graz Jewish community then had 135 members. At the University of Graz a Center for Jewish Studies was established. In January 2001 the Vienna Jewish community celebrated the 175th anniversary of the historic Stadttempel together with President Thomas Klestil and tenor Neil Shicoff. In contrast to the jubilees in 1976 and 1988 they did not publish a Festschrift. In June 2001 the Jewish community of Salzburg – which had 70–80 members – celebrated its 100th jubilee together with President Thomas Klestil. In 2004, at the University of Salzburg, a Center for Jewish Cultural Studies was founded. In 1999 the Jewish community founded a Holocaust victim's information and support center. In 2000 the Austrian Reconciliation Fund was created in order to compensate forced laborers in the NS era. In January 2001 U.S. President Bill Clinton's deputy secretary of finance and chief negotiator for restitution Stuart *Eizenstat and the Austrian government agreed on the sum of $360 million. With this money the General Settlement Fund, which is administered by the National Fund, was created. The Fund received about 20,000 applications, but was still not effective. Austria demanded a legally binding guarantee that no further legal action would be taken by anyone for restitution, which was not possible because of several ongoing class actions in the U.S. In June 2002 the Jewish communities signed an agreement with the Austrian federal provinces, which pledged to pay 18.2 million Euro in the next five years as restitution for stolen community property. The city of Vienna promised to rebuild the premises of the historic Jewish Ha-Koaḥ sports club. From 1945 until 1980 the community had to sell 170 of its 230 real estate properties in order to cover its deficit. After 1980 it had to apply for bank credit in order to cover its expenses. In 2003 the financial situation of the community became extremely difficult. Reports in the national and international press spoke about the possible closing down of the Jewish community. In the end the insolvency of the Jewish community was prevented through an advance payment of half of the Austrian provincial restitution money. Finally, in May 2005 an agreement was reached for payment of 18.2 million Euro by the Republic of Austria to the Vienna Jewish community, which therefore withdrew its applications to the General Settlement Fund. Beginning in the 1980s, in Vienna and in the provinces a number of plaques or monuments commemorating destroyed synagogues or Jewish communities were erected. In November 2002 Austrian President Thomas Klestil unveiled a monument in memory of the 65,000 Austrian Holocaust victims in the hall of the Stadttempel. In 2001 a Center for Austrian Studies, financed by the Austrian Society of the Friends of the Hebrew University, was opened at the Hebrew University. Its academic chair was Robert S. Wistrich; its first director was Professor Hanni Mittelmann. In autumn 2003 the federal land of Lower Austria, the city of Baden, and the Jewish community of Vienna decided to finance the renovation of the historic synagogue in Baden near Vienna. In February 2004 a rabbinical conference of the Chabad movement was held in Vienna, with more than a hundred rabbis participating. The guest of honor was Romano Prodi, head of the EU commission, who was personally blessed by the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, Yonah Metzger. In July 2004 a square on the Vienna park ring was named after Theodor Herzl. Austria, Hungary, and Israel issued, uniquely, a joint and identical stamp with the portrait of Herzl. The city of Vienna held its fifth international Herzl Symposium. In autumn 2004 the statutes of the Vienna Jewish community were changed and the federal association of the Austrian Jewish communities (Bundesverband der israelitischen Kultusgemeinden) became the Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft. This meant that instead of being an association it was now a state corporation (Koerperschaft des oeffentlichen Rechts). In November 2004 the Vienna Jewish community had 6,894 members. It was estimated that altogether about 14,000 Jews lived in Austria. COMMUNAL AND CULTURAL LIFEFrom 1990 Chief Rabbi Chaim Eisenberg organized an annual cantorial concert with distinguished international cantors. In 1993 and 1994 they took place in the former synagogues of Mikulov (Nikolsburg) and Trebitsch in Moravia in order to help with their renovations. In spring 1992 a week of Jewish culture was for the first time part of the Vienna "Festwochen." It was organized in collaboration with the city of Vienna, and attracted over 10,000 people. From 1990 Vienna also had a Jewish street festival and annual Jewish film festival. In 1991 a Jewish museum opened in Hohenems in the Austrian province of Vorarlberg; its director was Hanno Loewy. In November 1993 the Jewish Museum of the city of Vienna, which was initiated by the Vienna mayor Helmut Zilk, was opened in the historic Palais Eskeles in the heart of Vienna by the Vienna-born mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek. Its first ANTISEMITISMWhen in October 1991 the Jewish cemetery of Vienna was desecrated, 10,000 people took part in a silent march against antisemitism in Vienna. In October 1992, the Jewish cemetery of Eisenstadt was desecrated and Chancellor Vranitzky and Paul Grosz attended a commemorative ceremony. In spring 1991 Jörg Haider, the populist leader of the Freedom Party, praised the "decent and proper employment policies" in Nazi Germany, for which he was voted out of office as governor of Carinthia. A year later a committee of prominent artists and publicists organized a "concert for Austria" on the Heldenplatz in Vienna against rightist tendencies in Austrian politics. Elie *Wiesel was invited to speak from the huge balcony, the first person since Hitler to speak from there. Even more people – about 250,000 – took part in a "sea of lights" in January 1993 opposing a petition of Haider's Freedom Party against the immigration of foreigners, which was signed by 417,000 people, far fewer than expected. In May 1992 the popular columnist of the country's most widely read daily Neue Kronen Zeitung, Richard Nimmerrichter, published two articles in which he asserted that relatively few Jews had been gassed and that anyone who survived Hitler would also survive Mr. Grosz, the president of the Vienna Jewish community. The Jewish community and Paul Grosz subsequently sued Nimmerrichter, winning partial victories in eight trials and getting the newspaper to moderate its tone. In 1995 German television showed a video of a meeting of former SS-men in the Austrian village of Krumpendorf with Heinrich Himmler's daughter as guest of honor. At the meeting Jörg Haider praised the SS-men for having remained decent and despite enormous pressures loyal to their convictions until today. Opinion polls throughout these years showed that the number of antisemites in the Austrian population can be estimated at 20%. In 1994 and 1995, Austria was shocked by several neo-Nazi terrorist bombings. In December 1993, a letter bomb was sent to the popular Social Democrat mayor of Vienna, Helmut Zilk, which cost him his left hand and almost killed him. In the same week, letter bombs were sent to several politicians, journalists, and other people working for the integration of foreigners; three of them were injured. The letter bombs were sent by the mentally ill Austrian neo-Nazi and antisemite Franz Fuchs. He also planted a bomb which killed four gypsies. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and committed suicide. In 1997 the monthly magazine Wiener published an article by Thomas Köpf entitled "Scandal in the Jewish Community, Good Business with a Bad Conscience," which was full of antisemitic stereotypes and phrases and illustrated with a red Magen David composed of bank notes. The Jewish community responded with a press conference and a court order and received an apology. [Evelyn Adunka (2nd ed.)] Austria-Israel RelationsThe establishment of relations between Austria and Israel was involved with the question of whether the 1938 Anschluss, by which Austria became part of Nazi Germany, should influence the relations between the two countries. The government of Israel adopted the thesis that was at the basis of the Austrian "State Treaty"; that is, that Austria was the victim of Nazi aggression in 1938. However, the adoption of this policy encountered obstacles of public opinion in Israel arising out of Austria's identification with Germany. Great significance was ascribed to Austria's unsatisfactory response to Jewish claims for restitution and indemnification for crimes committed by the Nazi regime in Austria. This situation gradually changed as a result of Austria's friendly attitude to Israel in the context of the implementation of the "State Treaty," which imposed complete neutrality upon her. Austria's political stand at the un, as well as in other international arenas, and her support of Israel during the *Six-Day War, contributed much to the development of friendly ties. Relations were established on a consular level almost immediately after the formation of the State of Israel. From 1956, normal diplomatic relations existed, which soon were on the ambassadorial level. Friendship leagues exist in the two states, as well as mutual chambers of commerce. Trade between Israel and Austria steadily increased since 1948. In 1968 Israel exported $6.8 million worth of goods to Austria, headed by citrus fruits (of which Israel was the main supplier to Austria) and phosphates and chemicals. Austria exported $6.2 million worth of goods to Israel, chiefly timber and machinery. By 2002 the figures had risen to $68 million (mostly manufactured goods) and $154 million, respectively. [Yohanan Meroz] Austria declared itself in favor of Security Council Resolution 242 of November 1967. It voted for the right of Yasser Arafat, then leader of the PLO, to address the United Nations General Assembly, but the Austrian delegation abstained on the vote to grant the PLO observer status at the UN. The visit of Israel foreign minister Shimon Peres in November 1992 and his official invitation to President Klestil and Chancellor Vranitzky to Israel, together with the inauguration of several Austrian-Israeli projects, marked a new era in the relationship of the two countries. In 1994 four leading Austrian politicians – President Thomas Klestil, Chancellor Franz Vranitzky, Vice Chancellor Erhard Busek, and the president of Parliament, Heinz Fischer – visited Israel. This demonstrated the excellent relations between Austria and Israel since Kurt Waldheim's presidency In 1997 Prime Minister Benjamin Netanjahu visited Austria. During his visit in the Stadttempel he appealed to the Jews of Austria to immigrate to Israel. In 2002 the Austrian minister for foreign affairs Benita Ferrero-Waldner and the secretary of state for the arts Franz Morak and the then president of Parliament Heinz Fischer visited Israel. In December 2003 the charge d'affaires of the state of Israel Avraham Toledo was appointed ambassador. (In 2000 Israel formerly withdrew its ambassador because of the inclusion of Jörg Haider's Freedom Party in the Austrian government.) In October 2004 the first state visit of an Israeli president took place in Austria. During four days President Moshe *Katzav visited amongst other places the Stadttempel and the Mauthausen concentration camp. [Evelyn Adunka (2nd ed.)] BIBLIOGRAPHY:J. Fraenkel (ed.), The Jews of Austria. Essays on their Life, History and Destruction (1967), includes bibliography; S. Eidelberg, Jewish Life in Austria in the xvth Century… (1962); D. van Arkel, Anti-semitism in Austria (1966); P.G.J. Pulzer, Rise of Political Anti-semitism in Germany and Austria (1964); idem, in: Journal of Central European Affairs, 23 (1963), 131–42; R.A. Kann, Study in Austrian Intellectual History (1960); idem, in; JSOS, 10 (1948), 239–56; Silberner, in: HJ, 13 (1951), 121–39; J.S. Bloch, Reminiscences (1927); Freud, in: BLBI, 3 (1960), 80–100; J. von Wertheimer, Juden in Oesterreich, 2 vols. (1892); J.E. Scherer, Rechtsverhaeltnisse der Juden in den deutsch-oesterreichischen Laendern (1901); N.M. Gelber, Aus zwei Jahrhunderten (1924); S. Baron, Judenfrage auf dem Wiener Kongress (1920); M.J. Kohler, Jewish Rights at the Congress of Vienna… (1918); S. Krauss, Wiener Geserah vom Jahre 1421 (1920); L. Moses, Juden in Niederoesterreich (1935); Festschrift zur Feier des 50jährigen Bestandes der Union oesterreichischer Juden (1937); I. Smotricz, Mahpekhat 1848 be-Ostriyyah (1957); Y. Toury, Mahpekhah u-Mehumah be-1848 (1967), index. HOLOCAUST: T. Guttmann, Dokumentenwerk…, 2 vols. (1943–45); O. Karbach, in: JSOS, 2 (1940), 255–78; H. Rosenkranz, in: Yad Vashem Bulletin, 14 (1964), 35–43; idem: Kristallnacht in Oesterreich (1968); H. Gold, Geschichte der Juden in Wien (1966); H. Gold, Geschichte der Juden in Oesterreich (1971); G. Reitlinger, The Final Solution (1953), index; R. Hilberg, Destruction of the European Jews (1961), index; H.G. Adler, Theresienstadt (Ger., 19602); I. Friedmann, in: JSOS, 27 (1965), 147–67, 236, 249; J. Moser, Die Judenverfolgung in Oesterreich 1938–1945 (1966). POSTWAR PERIOD: F. Wilder-Okladek, The Return-Movement of Jews to Austria after the Second World War (1969); A. Tartakower, Shivtei Yisrael, 2 (1966), 315–23; Y. Bauer, Flight and Rescue (1970); L.O. Schmelz, in: Deuxième colloque sur la vie juive dans l'Europe contemporaire (Eng. 1967). ADD. BIBLIOGRAPHY: T. Albrich, Wir lebten wie sie. Juedische Lebensgeschichten aus Tirol und Vorarlberg (1999); H. Brettl, Die juedische Gemeinde von Frauenkirchen (2003); D.A. Binder, G. Reitter, and H. Ruetgen, Judentum in einer antisemitischen Umwelt. Am Beispiel der Stadt Graz 1918–1938 (1988); K.H. Burmeister (ed.), Rabbiner Dr. Aron Tänzer. Gelehrter und Menschenfreund 1871–1937 (1987); D. Ellmauer, H. Embacher, and A. Lichtblau (eds.), Geduldet, geschmaeht und vertrieben. Salzburger Juden erzählen (1998); H. Embacher (ed.), Juden in Salzburg. History, Cultures, Facts (2002); M.M. Feingold (ed.), Ein Ewiges Dennoch. 125 Jahre Juden in Salzburg (1993); D. Herzog, Erinnerungen eines Rabbiners 1882–1940 (1995); Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Graz, Geschichte der Juden in Suedost-Oesterreich (1988); R. Kropf (ed.), Juden im Grenzraum (1993); G. Lamprecht (ed.), Juedisches Leben in der Steiermark (2004); A. Lang, B. Tobler, and G. Tschoegl (eds.), Vertrieben. Erinnerungen burgenlaendischer Juden und Juedinnnen (2004); E. Lappin (ed.), Juedische Gemeinden. Kontinuitaeten und Brueche (2202); A. Lichtblau (ed.), Als haetten wir dazugehoert. Oesterreichisch-juedische Lebensgeschichten aus der Habsburgermonarchie (1999); C. Lind, …es gab so nette Leute dort. Die zerstoerte juedische Gemeinde St. Poelten (1998); idem, …sind wir doch in unserer Heimat als Landmenschen aufgewachsen…. Der Landsprengel der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinde St. Poelten (2002); idem, Der letzte Jude hat den Tempel verlassen. Juden in Niederoesterreich 1938–1945 (2004); G. Milchram, Heilige Gemeinde Neunkirchen (2000); P. Schwarz, Tulln ist judenrein! (1997); W. Neuhauser-Pfeiffer and K. Ransmaier, Vergessene Spuren. Die Geschichte der Juden in Steyr (1993); F. Polleroß (ed.), Die Erinnerung tut zu weh. Juedisches Leben uns Antisemitismus im Waldviertel (1996); J. Reiss (ed.), Aus den sieben Gemeinden (1997); W. Sotill, Es gibt nur einen Gott und eine Menschheit. Graz und seine juedischen Mitbuerger (2001); S. Spitzer (ed.), Beitraege zur Geschichte der Juden im Burgenland (1994); S. Spitzer, Die juedische Gemeinde von Deutschkreuz (1995); S. Spitzer, Bne Chet. Die oesterreichischen Juden im Mittelalter (1997); R. Streibel, Ploetzlich waren sie alle weg. Die Juden der ‚Gauhauptstadt Krems' und ihre Mitbuerger. (1991); W. Wadl, Geschichte der Juden in Kaernten in Mittelalter (1981); A. Walzl, Die Juden in Kärnten und das Dritte Reich (1987). For further bibliography see *Vienna. Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica. © 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved. |

|

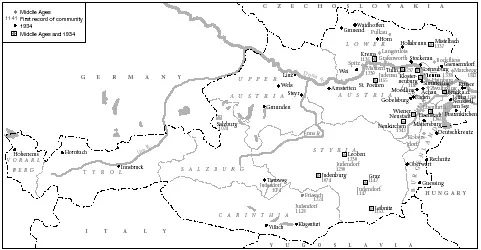

Jewish population of Austria in Middle Ages and 1934.

Jewish population of Austria in Middle Ages and 1934.

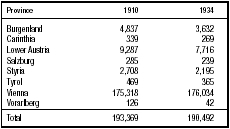

Jews in Austrian Provinces

Jews in Austrian Provinces