Sigmund Freud

(1856 - 1939)

Sigismund Schlomo Freud was born on May 6, 1856, to Jewish parents in Freiberg, Moravia, now Pribor, in the Czech Republic, the son of Jacob Freud and his third wife Amalia (20 years younger than her husband). Sigi, as his relatives would call him, was followed by seven younger brothers and sisters.

His family constellation was unusual because Freud’s two half-brothers, Emmanuel and Philipp, were almost the same age as his mother. Freud was slightly younger than his nephew John, Emmanuel’s son. This odd situation may have triggered Freud’s interest on family dynamics, leading to his ulterior formulations on the Oedipus Complex.

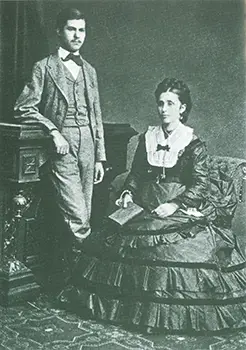

Freud age 16 with mother Amalia in 1872 |

Freud’s father, a Jewish wool merchant of modest means, moved the family to Leipzig, Germany (1859), and then settled in Vienna (1860), where Freud remained until 1938.

He abbreviated his name to Sigmund Freud in 1877.

Having considered studying law previously, he decided instead on a career in medical research, beginning his studies at Vienna University (1873) at age 17. As a student, Freud began research on the central nervous system guided by Ernst von Brücke (1876), and qualified as Doctor of Medicine in 1881. He worked at the Theodor Meynert’s Psychiatric Clinic (1882-83) and later studied with renowned neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, at the Salpetrière, in Paris (1885). Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis.

From 1884 to 1887, Freud published several articles on cocaine. “So coca is associated above all with my name” he wrote to Martha Bernays on January 16, 1885.

He married Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg, in 1886. The couple had six children (Mathilde, 1887; Jean-Martin, 1889; Olivier, 1891; Ernst, 1892; Sophie, 1893; Anna, 1895).

His interest in hysteria was stimulated by Josef Breuer’s and Charcot’s use of hypnotherapy (1887-88). Once he had set up in private practice back in Vienna in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work specializing in nervous disorders.

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. He believed smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it. Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker. Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, “the one great habit.”

Freud read William Shakespeare in English throughout his life, and it has been suggested that his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare’s plays. Freud’s Jewish origins and his allegiance to his secular Jewish identity also influenced the formation of his intellectual and moral outlook, especially with respect to his intellectual non-conformism, as he admitted in his Autobiographical Study. They would also have a substantial effect on the content of psychoanalytic ideas, particularly in respect of their common concerns with depth interpretation and “the bounding of desire by law.”

Freud moved to a flat in Berggasse 19 (1891), which was turned into The Freud Museum in 1971.

Freud and Breuer published their findings in Studies on Hysteria (cathartic method) in 1895; in the same year, Freud was able to analyze, for the first time, one of his own dreams, subsequently known as “The Dream of Irma’s Injection.” He also wrote 100 pages of draft manuscript that were published only after his death, under the name of Project for a Scientific Psychology (1950).

The inconsistent results of Freud’s early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having concluded that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition, about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them. In conjunction with this procedure, which he called “free association.” By 1896, he was using the term “psychoanalysis” to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.

Freud’s development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a “neurasthenia” which he linked to the death of his father in 1896 and which prompted a “self-analysis” of his own dreams and memories of childhood. His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother’s affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses.

On the basis of his early clinical work, Freud had postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud’s seduction theory. In the light of his self-analysis, however, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and that in either case they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.

This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes an autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud’s subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus Complex.

The Interpretation of Dreams (“Die Traumdeutung”), which Freud considered the most important of all his books, was published in 1899, bearing 1900 as printing date, because he wanted his great discovery to be associated with the beginning of a new century.

The medical world still regarded his work with hostility and he worked in isolation. He started analyzing his young patient Dora, the pseudonym for Ida Bauer given by Freud to a patient whom he diagnosed with hysteria. Her principal hysterical symptom was aphonia, or loss of voice. Freud interpreted Ida’s hysteria as a manifestation of her jealousy toward the relationship between her father and another woman.

in 1901, Freud’s book, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life was published.

In 1902, Freud at last realized his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor. The title “professor extraordinarius” was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of “professor ordinarius” in 1920). Despite support from the university, his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was secured only with the intervention of one of his more influential ex-patients, a Baroness Marie Ferstel, who (supposedly) had to bribe the minister of education with a valuable painting.

Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Jokes and their relation to the Unconscious, Fragments of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria (Dora) were published in 1905.

A number of Viennese physicians who had expressed interest in Freud’s work were invited to meet at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology. This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft), later (1908), the Viennese Association of Psychoanalysis, and its meetings marked the beginning of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.

Max Graf, a member of the group described the meetings:

By 1906, a small group of followers had gathered around Freud, including William Stekel, Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Abraham Brill, Eugen Bleuler and Carl Jung. Sándor Ferenczi and Ernest Jones joined the psychoanalytical circle and the “First Congress of Freudian Psychology” took place in Salzburg, which attracted some forty participants from five countries (1908).

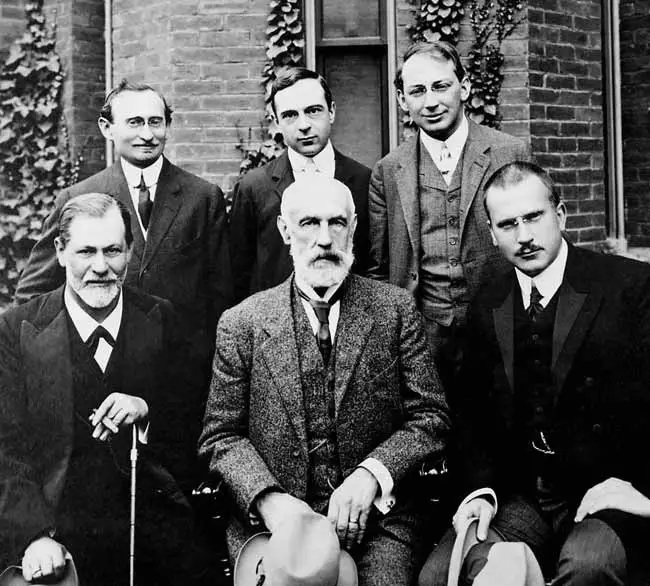

Group photo 1909 in front of Clark University. Front row: Sigmund Freud,

G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung; back row: Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi

In 1909, Freud was invited by Stanley Hall to deliver five lectures at Clark University in Massachusetts, which abstracted the contents of his six previously published books. Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis was the German version of this set of lectures, published in 1910. Even though this was his only visit to the United States, it helped draw the world’s attention to his work.

The psychoanalytic movement grew and a worldwide organization called the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) was founded in 1910. The psychoanalytical magazine Imago was founded in 1912.

As the movement spread, Freud had to face the dissension among members of his original circle. Adler (1911) and Jung (1913) left the Viennese Association of Psychoanalysis, and formed their own schools of psychology, disagreeing with Freud’s emphasis on the sexual origin of neurosis.

The first part of the Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis was published in 1916 and The International Journal of Psychoanalysis (IJPA) was founded in 1920.

Freud found out he had cancer of the jaw in 1923; nevertheless, he remained productive, enduring painful treatment and 33 surgeries. He still refused to give up smoking cigars.

The first volumes of Freud’s Collected Works appeared in 1925, a time of his conflicts with Otto Rank.

Freud was honored with the Goethe Prize for Literature (1930) and was elected Honorary Member of the British Royal Society of Medicine (1935).

After Hitler became Chancellor of the German Reich in 1933 and the Nazi party decreed that any book, “which acts subversively on our future or strikes at the root of German thought, the German home and the driving forces of our people...” was to be burnt. Freud remarked to his friend Ernest Jones: “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.”

Nevertheless, Freud underestimated the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss and the subsequent violent outbreaks of anti-Semitism. Jones, the then president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), flew to Vienna from London on March 15, 1938, determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain. This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave Austria.

Freud immigrated to England with his family, arriving in London on June 6, 1938. They moved into a house at 20 Maresfield Gardens, which was turned into the Freud Museum in 1986. He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness. He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis, which was published posthumously.

The Freud Museum in London

Freud died in London on September 23, 1939, at the age of 83.

Sources: The Freud Page.

“Sigmund Freud,” Wikipedia.

Photos: Portrait Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Young Freud Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Freud home Lerner, CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Clark University Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Freud Museum Rup11, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.