Leo Frank

(1884 - 1915)

The success of the Broadway musical Parade has rekindled interest in the Leo Frank case. In 1913, Frank was convicted of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13 year old employee of the Atlanta pencil factory that Frank managed. After his death sentence was commuted by Georgia's governor, a mob stormed the prison where Frank was being held and lynched him. Frank became the only known Jew lynched in American history. The case still spurs debate and controversy — along with Broadway success. What are the facts of the Frank case?

“Little Mary Phagan,” as she became known, left

home on the morning of April 26 to pick up her wages

at the pencil factory and view the Confederate Day

Parade. She never returned home. The next day, the

factory night watchman found her sawdust-covered body

in the factory basement. When Frank, who had just completed

a term as president of the Atlanta chapter of B'nai

B'rith, was asked to view the body, he became agitated,

confirmed personally paying Mary tier wages, but could

not say where she went next. Frank, the last to see

Mary alive, became the prime suspect.

Georgia's solicitor general, Hugh Dorsey, sought a grand jury indictment against Frank. Rumor circulated that Mary had been sexually assaulted. Factory employees offered apparently false testimony that Frank had made sexual advances toward them. The madam of a house of ill repute claimed that Frank had phoned her several times, seeking a room for himself and a young girl. At a time when the cult of Southern chivalry made it a “hanging crime” for African-American males to have sexual contact with the “flower of white womanhood,” these accusations against Frank, a Northern-born, college-educated Jew, proved equally inflammatory.

For the grand jury, Hugh Dorsey painted Leo Frank as a sexual pervert who both was homosexual and preyed on young girls. What he did not tell the grand jury was that a janitor at the factory, Jim Conley, had been arrested two days after Frank when he was seen washing blood off his shirt. Conley then admitted writing two notes found by Mary Phagan's body. The police assumed that, as author of these notes, Conley was the murderer; but Conley claimed, after apparent coaching from Dorsey, that Leo Frank had confessed murdering Mary in the lathe room and paid Conley to pen the notes and help him move Mary's body to the basement.

Even after Frank's housekeeper placed him at home, having lunch, at the time of the murder and despite gross inconsistencies in Conley's story, both the grand and trial jury chose to believe Conley This was a rare instance of a Southern black man's testimony being used to convict a white man. In August of 1913, the jury found Frank guilty in less than four hours while crowds outside the courthouse shouted, “Hang the Jew.” Historian Leonard Dinnerstein reports that one juror had been overheard to say before his selection for the jury, “I am glad they indicted the G-d damn Jew. They ought to take him out and lynch him. And if I get on that jury, I'll hang that Jew for sure.”

Facing intimidation and mob rule, the judge sentenced Frank to death. He did not allow Frank in the court room on the grounds that, had he been acquitted, Frank might have been lynched by the crowd outside.

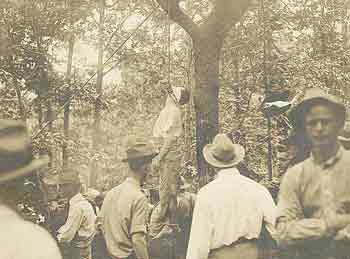

Lynching of Leo Frank, Marietta, Georgia

August 17, 1915. Postcard, gelatin silver print. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Division |

Despite these breaches of due process, Georgia's higher courts rejected Frank's appeals, and the U. S. Supreme Court voted, 7-2, against reopening the case, with justices Holmes and Hughes dissenting. Frank's survival depended on Georgia governor Frank Slaton. After a 12-day review of the evidence and letters recommending commutation from the trial judge (who must have had second thoughts) and from a private investigator who had worked for Hugh Dorsey, Slaton commuted Frank's sentence to life imprisonment. That night, state police kept a protesting crowd of 5,000 from the governor's mansion. Wary Jewish families fled Atlanta. Slaton held firm. “Two thousand years ago,” he wrote a few days later, “another Governor washed his hands and turned over a Jew to a mob. For two thousand years that governor's name has been accursed. If today another Jew [Leo Frank] were lying in his grave because I had failed to do my duty, I would all through life find his blood on my hands and would consider myself an assassin through cowardice.” A year later Dorsey soundly defeated Slaton's bid for reelection.

Soon after the commutation, on August 17, 1915, a group of 25 men, described by peers as “sober, intelligent, of established good name and character“ stormed the prison hospital where Leo Frank was recovering from having his throat slashed by a fellow inmate. They kidnaped Frank, drove him more than 100 miles to Mary Phagan's hometown of Marietta, Georgia, and hanged him from a tree. Frank conducted himself with dignity, calmly proclaiming his innocence. Townsfolk were proudly photographed beneath Frank's swinging corpse, pictures still valued today by their descendants.

Some two weeks after the lynching, Rabbi Stephen

Wise wrote to Henry Morgenthau, Sr.,

noting that “the situation is becoming very

hard for the Jews in the little towns, many of whom

are being boycotted.”

Southern Jewish historians note that Atlanta Jewry

has still not fully recovered from the trauma of the Leo Frank case,

and that the Temple bombing of the early 1960s simply reopened those

wounds. Another legacy of the case is that, to help defend Frank, B'nai

B'rith created its (now-independent) Anti-Defamation League. In 1986,

the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles finally granted Leo Frank a

posthumous pardon, not on the grounds that they thought him innocent,

but because his lynching deprived him of his right to further appeal.

The descendants of Mary Phagan's family and their supporters still insist

on his guilt.

| |

Stephen

Wise (1874-1949) to Henry Morgenthau, Sr.,

(1856-1946).

Typescript letter, September 3, 1915.

Henry Morgenthau Papers.

Library of Congress Manuscript Division

|

Sources: American Jewish Historical Society

Portrait of Leo Frank: Leo Frank (1884-1915), August 26, 1913. Gelatin silver print with picture editor's marks. New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Collection. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

|