|

A History of the Abuyudaya Jews of Uganda

By Arye Oded (Israeli Ambassador to Kenya)King Mutesa I (1856-1884) of Buganda introduced far-reaching religious, social, and administrative reforms in his kingdom. He was motivated by various factors. This shrewd king eager for knowledge strove to strengthen his kingdom by utilizing the superior technology that he discovered among the Arab traders and the Europeans which visited him. His foreign policy was to gain the friendship of the Sultan of Zanzibar and the support of the Arab traders; from these he hoped to obtain weapons to establish his authority over his neighbours and prevent a possible Egyptian inversion from the North. This is why he declared himself a Christian and adapted some of the Laws of Islam. This conversion brought about a drastic change in the traditional local religion and social customs of the Buganda. Islam's penetration into Buganda indirectly helped the spread of Christianity. This struck at the roots of the established religion and paved the way for a monotheic faith. Although the first Christian missionaries (Protestants from 1877 and Catholics from 1879) were generally hostile to the Moslems and Islam, they admitted that the Moslem religion also had positive aspects and influences. The establishment and ultimate triumph of Christianity over the indigenous religion and Islam were furthered in the early 1890s by the arrival of the British and by their support of the Protestant missionaries. Captain F.J.D. Lugard and Captain J.R. MacDonald, representatives of the Imperial British East African Company, helped the Christians to rout the Moslems to convert Uganda into a Christian nation. However, Christianity appeared in Uganda in Western dress. The Christians not only wanted to teach the principles of the Christian religion, but also aspired to inculcate Western Civilization and uproot the local customs. Moreover, Christianity had a direct political purpose. The Protestant missionaries who came from England were called Abangereza, i.e. the English, by the local population, and the Catholic missionaries who came from Algiers, supported by France, were called Abafaransa, i.e. the French. From the outset, the two groups fought for key positions and influence in the state.

Namutumba Synagogue Subsequently, at the beginning of the twentieth century, religious movements with an Afro-Christian bent began to appear. These had broken away from the Christian church for religious, social and political reasons. They opposed the British administration and the white man's superiority in the Church hierarchy and demanded the establishment of African leadership. Moreover, reading the Bible brought to them by missionaries, they were surprised to notice differences between what is written in it and the way it was put into practice by the established churches. The Abayudaya Community arose out of one of these dissenting groups. Its founder, Semei Kakungulu, broke away from the church initially because of a personal quarrel with the British. Subsequently, his adherence to the Old Testament brought him step by step to Judaism. Semei Lulaklenzi Kakungulu is one of the most important and colourful personalities in Uganda history. A successful military commander, courageous and talented, he rose to fame in Buganda at the turn of the century. He was a major military and political figure and played a part in determining....Kakungulu was born in Koki Kingdom, the son of Semuwemba of the Ganda people who had emigrated from Buganda. Semuwemba rose to fame rapidly and was popular with the Koki King. However, before he could be appointed Prime Minister he fell a victim to a plot in the royal court, and together with his wife was executed. He was survived by three daughters and seven sons, one of whom was Semei Kakungulu. The latter escaped from Koki and reached the Buddu region in the Buganda kingdom. In 1884, his talented and persuasive personality secured his appointment by the King of Buganda as a District Chief. Kakungulu soon proved himself a gifted political leader and powerful military commander. He began to take an active part in the King's wars against his neighbours and the religious wars which broke out in Uganda as a result of the penetration of Islam and Christianity.

Kakungulu led the Buganda successfully in the wars against Bunyoro, their traditional enemy in the North, and against the rulers of Busoga in the East. During thes years, the Imperial British East African Company entered Buganda. One of the obstacles facing the British administrators was the Moslem-Arab minority, which despite its defeat in 1889, threatened the British rule. When in 1895 the Moslems rebelled again, Kakungulus help was requested by the British to subdue them. He gathered an army of seven thousand and attacked and defeated the Muslems. Lugard called him the first and most renowned warrior in Uganda. Kakungulus talented leadership was displayed in his conquests. He successfully subdued many of the large tribes surrounding the Buganda Kingdom, and even reached the Sudanese border in the north. In 1894 Uganda was formally annexed to the British Empire as a protectorate, and the British, who respected Kakungulus military abilities, gave him a free hand in his battles against the tribes. In fact, it was Kakungulu who led the spearhead of the army which at the end of the 19th century paved way for the British rule over wide areas of Uganda. There were few British soldiers in Uganda at that time, and without Kakungulu and his army it is doubtful whether the British could have controlled the country as easily and as quickly as they did. Between 1899 and 1902, Kakungulu conquered Tororo and Palisa Districts, then called Bukedi, to the north of North-Eastern Buganda and Busoga. In return for his aid, the British appointed Kakungulu military governor of Eastern province of Uganda (today Mbale, Tororo, and Palisa Districts). There he found the town of Mbale which developed rapidly and is now the third largest town of Uganda. However, Kakungulus aspirations were more daring and far-reaching. He cooperated with the British in the hope that they would recognize him as Kabaka of the Eastern region of Uganda and treat him like the other kings who ruled in Uganda. Already in 1900 he organized Bukedi as a Kingdom and acted as Kabaka, appointing chiefs and granting them territory. His position was reinforced by the British Special Commissioner to Uganda. Sir Harry Johnson, who visited Kakungulu in 1901 to seek his aid in subduing the Lango region in northern Uganda and suppressing the Sudanese soldiers serving in the British army who had rebelled against their officers. In return, Kakungulu asked the British Government to formally recognize him as King. According to him, Johnston had agreed to this request and from the correspondence between Kakungulu and the British Government on this issue, it appeared that he had good reason to believe that the British would appoint him Kabaka. In one of his letters, Kakungulu wrote: My being made Sultan is not my doing but that of Sir Harry Johnston, the Commissioner. When he saw the good work I had done for the Government, he made me King of the Bakedi...I accepted his words in good faith as the words of truthful people are always to be believed. But the British Government never intended to recognize Kakungulu as King, and the administrators who succeeded Johston notified him that his expectations were based on error. The British Sub-Commisioner of the Central Province remarked that...he [Kakungulu] had tangible reasons for being under the impression that he was or would be a Kabaka of Bukedi. As things turned out, he was disappointed in this respect. In the same letter, the Sub-Commisioner praised Kakungulu for his constructive efforts for the district: What was once a dreary waste is now flourishing with gardens and teeming with life. Good wide roads have been cut, rivers have been bridged and embankments made through marshy ground, all at his own expense and for the public use. His past services cannot be over-estimated. One reason for British opposition to Kakungulus becoming King was the belief that his Ganda affiliation made it undesirable for him to rule over other peoples. Another was his jealousy of his rivals, including the very influential Prime Minister of Buganda, Apollo Kagwa, who constantly suspected Kakungulu and saw him as a potential competitor. Moreover, unlike the other kings in Uganda, Kakungulu was not a royal prince. The issue of kingship caused tension between Kakungulu and the British, who threatened to attack him if he continued to style himself King. In 1902 the British deposed him in Bukedi, but in 1904 they compromised with him by appointing him a Saza Chief (Mbale County). In 1906 he was nominated President of the Lukiko of the Busoga District in Eastern Uganda in order to organize the local administration. Kakungulu continued his efforts to gain British recognition as King but in vein. Eventually he realized that in spite of all his efforts he would not achieve recognition as a ruler of his own kingdom and that in fact he had merely been used as a tool to facilitate the establishment of British rule in Uganda. In 1913 bitterness and disappointment caused him to resign from his positions in Busoga and to return to Mbale; he abandoned his military activities and began to concentrate on matters of faith and religion. In this field also Kakungulu demonstrated boldness and independence. Semei Kakungulu's Faith To JudaismThe disagreements which Kakungulu had with the British administration brought him closer to a breakaway from the Christian sect, the Malaki, so named after its leader Malaki Musajakawa who appeared in Uganda in 1913 and contested the British authorities on religious grounds. The Bamalaki (followers of Malaki) who called their movement K.O.A.B.-- an abbreviation of Katonda omu ayinza byona which means "God is omnipotent"-- were dissident protestants whose faith rested on their devotion to the Bible. Malaki was a disciple of Joswa Kate Mugema, a rich and influential Buganda chief who refused to recognize any authority but the Bible and differed from the protestants on many religious principles. He regarded Saturday as the Sabbath and requested the British authorities to accept this officially. To do so would have created difficulties at work and administrative problems, and thus Mugema clashed with the British on this issue. He began comparing himself to Moses who was sent by God to Pharoah (in this case, the British Government) and gave his nation a new code of laws. Mugema violently fought any sign of idol worship. He forbade his followers to eat pork, but allowed polygamy, claiming that the patriarch Abraham married more than one wife. In this too, he deviated from accepted Christian practice. But the most important principle in the new faith, which spread rapidly through Uganda (in 1921 there were about 100,000 believers), was violent opposition to the use of medicines and immunizations for humans and animals. Doctors were regarded as Satan's representatives. If God could save man from the burning fiery furnace (Daniel 3), he could definitely help them in time of illness, no matter how severe. There was no need for human aid--faith alone would suffice. The Malaki referred to the Old Testament on this question, quoting amongst many other verses, Jeremiah 46:11: In vein shall you use many medicines; for you shall not be cured. Their objection to immunization during an outbreak of plague resulted in violence between them and the British authorities. Their leader Malaki was exiled to northern Uganda in 1926 and died that year of a protracted hunger strike.Kakungulu, bitterly disappointed by the British authorities, willingly cooperated with the Malaki and helped to spread their creed throughout the Eastern Province from his centre in Mbale. Kakungulu began to study and meditate on the Old Testament for long periods. His attitude was stricter than that of the Abamalaki, and he demanded the observance of all Moses Commandments, including the law of circumcision. The Abamalaki opposed this, claiming that Jews did not believe in the New Testament and Jesus Christ. Kakungulu replied: If this was the case then from this day I am a Jew (Omuyudaya) This was in 1919. Kakungulu was circumcised, and he circumcised his first born son (Yuda). He circumcised his second son on eight days of birth and called him Nimrod (Nimulodi). He subsequently circumcised all his sons and urged his supporters and members of his family to observe this rite. Many of them did so. Kakungulu showed his devotion by calling his children Biblical names such as: Yuda, Israel, Nimrod, Abraham, Jonah, and Miriam. Kakungulu's circumcision of himself and his sons demanded that his followers observe this practice. The Ganda abhorred and forbade any mutilation of the body and regarded circumcision as a violation of their traditional law. (The Baganda are the only Bantu tribe who do not mutilate their persons.) Kakungulu compiled a special book of rules and prayers in Luganda for the members of his community. The book, which was printed in 1922, is called Ebigambo ebiva mukitabo ekitukuvu (Quotations from the holy book). The contents of the book show clearly how far Kakungulu had moved away from Christianity to Judaism. The book, ninety pages long, is actually a guide to the Jewish religion and a handbook for the teachers of the community. In it, Kakungulu continually demanded complete faith in the Old Testament and all its commandments. It is true, Kakungulu said, some claims that the Old Testament was old fashioned and anachronistic, but he himself did not believe this. They say,Kakungulu pointed out, that the era of Sabbath has passed. To them I say, Open Genesis 2:2-4 where it says And on the seventh day God ended his work which He had made, and he rested on the seventh day from his work which he had made. And God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it because that day he had rested from all his work which God created and made. Here God appointed the day of rest on the seventh day, Saturday, and one must not change it. Look also in the Book of Exodus 20:8-10, where it says in the Ten Commandments, Remember the Sabbath Day to keep it holy...God himself sanctified this day and commanded that it should be observed and how can we violate this commandment about the Sabbath? This is just one example which emphasizes how Bible study drew Kakungulu away from Christianity and how he regarded the Old Testament as the basis of his religion. In 1923 he built a small temple for himself and his followers near his house in Pangama. Some Christian leaders tried to influence Kakungulu to return to Christianity and in his book there is a letter from a Christian minister, L.M. Bingamu, sent from England on 15 July 1921. The Englishman wrote that he had heard of Kakungulu's search for the true road to God and stressed that �there is no true road other than brought by Jesus. Kakungulu replied that the right way was that of the Jews, quoting many verses from the Old Testament to prove this, including Zachariah 8:23: Thus says the Lord of hosts: In those days it shall come to pass that ten men shall take hold out of the languages of the nation, even shall take hold of the skirt of him that is a Jew, saying we will go with you: for we have heard that God is with you. Kakungulu concluded that this was clear evidence that one must join Jews. Kakungulu appointed teachers of the law, Abawereza, from his own mission school near his house. To be a confirmed Muwereza, one was to be able to read and write the Luganda language; he was to say the words found in Det. 32:1-44 in sweet melody at heart. Some of his Abawereza teachers of the law are mentioned below: (1) Yekoyasi Kaweke (2) Zakayo Mumbya (3) Zakayo Luwandi (4) Samson Mugombe (5) Yokana Keki (changed his name later to Jonadab) (6) Yokana Mulefu (7) Eria Musamba (8) Kezekia Sajjabi (9) Saulo Kutakulimuki (10) Zakayo Balozi (11) Isaac Kizito (12) Yokana Naide (13) Yakobo Were (14) Yakobo Kasakya (15) Yokana Wetege (16) Yakobo Bbosa (17) Mubale Petero (18) Daudi KamombaIn 1923 Kakungulu was obliged to retire from his last official post as a Saza Chief of Bukedi, as his religious opinions prevent his carrying out his duty as a chief. Kakungulu accepted a pension from the British Government. In 1926 an additional stage began in the Abayudaya's approximation to Judaism as a result of Kakungulu's meeting with a Jewish trader named Joseph. In that year Kakungulu went to Kampala to attend a lawsuit over land ownership, and there he met Joseph. A strong, sincere friendship developed. Joseph was amazed to hear of Kakungulu's conversion to Judaism, but was more astonished at his Jewishness and his confused concepts of Judaism and its relationship to Christianity and the New Testament. But he agreed to Kakungulu's request to instruct him in the Jewish faith. Kakungulu invited Joseph to his home in Mbale, where he stayed for about six months teaching Kakungulu the principles of Judaism. Following the meeting with Joseph great changes took place in the religious life of the Abayudaya: they ceased to believe in the New Testament and Jesus Christ. In order to prevent any confusion, Kakungulu instructed them not to use the word Mukama, meaning Lord, which to him designated Jesus Christ and instead ordered the use of the word Yakuwa, meaning God. They kept the Sabbath strictly and transgressors were severely punished; they prepared their Sabbath food on Fridays; they began to work on Sundays; they deleted all the Christian prayers from their book Kakungulu began to compile a new book devoid of quotations from the New Testament, but he died before he was able to publish it. Joseph had taught them the blessings and also the customary Jewish prayers. Head-covering was practiced, and Kakungulu began to wear a white Jewish robe which he had seen in Joseph's possession. The teachers at the school which Kakungulu built for the community were turbans similar to those which Kakungulu had seen in pictures of the early Jews circulated by the missionaries. The custom of baptizing children was stopped. Joseph taught Kakungulu the slaughtering ritual and the Abayudaya ate only meat slaughtered by themselves. The months of the year were called by their Hebrew names and all the festivals and feasts were celebrated. Kakungulu even divorced his wife, whose marriage was not in accordance with Jewish Laws. She was a Protestant and refused to become Jewish. Joseph began to teach Kakungulu and the elders of the community the Hebrew alphabet. None of the elders remember where Joseph came from although some think it was Ethiopia or even Jerusalem. Before Joseph left, he presented Kakungulu with a large Bible written in Hebrew and English. The elders of the community also tell of Kakungulu's meeting in Kampala at that time with another Jew called Moses, who used to accompany Joseph when teaching Kakungulu. Kakungulu did not force Judaism on his subordinates, tenants and members of his household, but tried to persuade them of the truth of his religion through explanations and deeds. Kakungulu liked to conduct the prayer service, deliver sermons and explain principles of the Jewish faith. Those of his people who agreed to accept Judaism were granted easier terms at work and more honourable status. Kakungulu gave the converts presents and clothes, paid their taxes and took a paternal interest in them (according to Samson Mugombe who mentioned that this is one of the reasons for conversion). The elders of the Abayudaya community recall that in 1927 Kakungulu met a third Jew called Isaiah Yari. Isaiah was a foreman during the construction of the Uganda railway in the town of Tororo, which is about 28 miles from Mbale. He approached Kakungulu requesting him to provide labourers. Isaiah treated the Abayudaya well, rested with them on Sabbath and prayed with them. He and his son Solomon met Kakungulu several times and taught him more about Judaism emphasizing that the Jews did not believe in Jesus Christ. According to the leader of the group of Abayudaya labourers, Elia Musamba, Isaiah was transfered to elsewhere after a month in Tororo because he refused to make the Abayudaya work on the Sabbath (Saturday). Until his death, Kakungulu maintained his oppositions to the use of medicines, believing that the Bible forbade it. He even refused to let his cattle be inoculated. On this issue there were many misunderstandings between Kakungulu and the British administrators, and when the latter inoculated 1200 heads of Kakungulu's cattle against his wishes, he decided to present these cattle to the Government having been inoculated. Despite his encounters with Jews, who certainly told him that the use of medicines was not against the Law, he did not retract his opposition to doctors and medicines. Kakungulu died in Mbale on 24 November 1928 by which time, according to the elders, the Abayudaya numbered approximately two thousand. Kakungulu was survived by four sons: Yuda Makabee (who was apparently sickly, but refused medical care by Kakungulu), Nimrod, Ibulaim Ndaula, and Israel. Ibulaim Ndaula became a Christian after his father's death. Ten years after Isaiah's visit, the Abayudaya met another Jew, David Solomon, who was born in India and arrived in Uganda in the late Twenties'. In 1937 Solomon was instructed to establish a pumping plant near Mbale. he recounts how, when he was in Mbale, some ten Africans appeared, wearing white robes and head coverings and watched him with much curiosity. When he asked what they wanted, they answered that they had heard he was a Jew, and therefore, they came to visit him because they themselves were Jews. At first Solomon thought the Africans were mocking him; but when they showed him a copy of the Bible in Hebrew with an English translation (received from Joseph) and described some of the principles of the Jewish religion, he was convinced that they really were Jews. From then on he visited the Congregation in the course of his work and sent them Hebrew calenders. Organization of the Community From 1928-1986The community was organized along the lines laid down by Kakungulu. The principle officers in the community were the secular leader, the religious leaders and teachers. The secular leader who was in charge of temporal matters was the most influential man in the community whose loyalty he commanded. The religious leader was the final authority on spiritual problems, which he solved on the basis of the Old Testament. He conducted the prayer services and acted as a circumciser (mohel). He was called the Levite or Kabona which in Luganda stands for priest (kohen in Hebrew). This function was derived from Ezekiel 44:33: You shall give unto the priest the first of your dough, that he may cause the blessing to rest in thine house. Kakungulu combined the secular and the religious leadership. He determined religious questions and conducted the prayers. Before his death he appointed his friend Isaka Kizito as his successor. The latter had also belonged to the Malaki sect and had later become a Jew. However, he refused the appointment and in his place Kakungulu designated Katikiro (Prime Minister) Yekoyasi Kaweke. Kaweke was succeeded in 1944 by Samson Mugombe. The first priest was Paulo (who changed his name to Saulo). He was later succeeded by Zakayo Mumbya.

After being briefed about the division, Oded called on a joint meeting to reconcile the two parties. Both Samson and Zakayo participated in this meeting. When it became clear that Samson Mugombe and his followers were observing Jewish Laws with greater strictness and correctness, Zakayo abandoned his opposition to Mugombe and the schism was healed. Zakayo had limited authority, and, because he was in poor health, his influence was almost negligible. Nevertheless he was regarded as the most important elder and was consulted on religious matters. Another clearly defined group is the teachers or Abawereza. These were responsible for the education of converts who joined the community. They taught Jewish Laws in the synagogue on festivals and Sabbaths. Abayudaya Observance of the Jewish Laws and CustomsThe Abayudaya regarded themselves as Jews. They realized, however,

that their isolation from the Jewish world had prevented them from

learning all the rules and commandments. Nevertheless, they strove to

be perfect Jews and wished to acquire knowledge of those laws on

which they had been unable to obtain instruction. The Old Testament

had been their only guide and the observance of every law prescribed

in it, including circumcision, fasts, prayers, festivals and

Sabbaths.

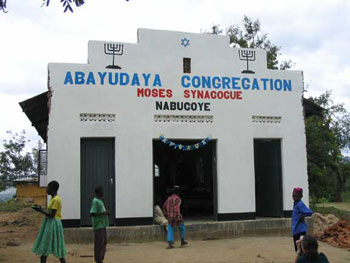

The centre of the community life was the Nabugoye on Nabugoye Hill. Semei Kakungulu ordered a twenty-acre area be set aside for the synagogue and school, and he also instructed that the rent from the tenants who lived on that land be solely for the use of the development of the community. Kakungulu himself began the foundations for what he called the House of God (Enyumba ya Katonda), but did not live to complete it. The synagogue which the Abayudaya built on this land was poor structure, fifty meters long by ten metres wide, consisting of a wooden frame and plastered over. Only in 1964, by means of a contribution of $100 received from the World Union for the Propagation of Judaism were they able to lay a concrete floor. The synagogue was long called the Jewish church until the community learned the Jewish place of worship was called a synagogue. Since then it has been called Moses Synagogue. It lacked both the Holy Ark and Scroll of Law, neither of which had been seen by any Abayudaya elders. The Old Testament was the only holy book they possessed. Their alter was a simple wooden table traditionally covered by three cloths coloured light blue, red and white, laid on on top of the other. This custom was introduced by Kakungulu on the basis of the verse in the Bible which describes the ephod as gold and blue and purple and scarlet (Exodus 27:8). Worshippers covered their heads, most commonly with a white skully turban. Two large drums were suspended on a tree near the synagogue to call the Congregation for prayer. The Congregation met for prayer in the synagogue on Sabbath and festivals. During the week the Abayudaya prayed at home. The only prayer book was the Old Testament; the old prayer book with its strong Malaki influence had been abolished. The Sabbath and festival prayers included the section beginning Give ear...(Deuteronomy 32). The Congregation sang the verses of the section to a pleasant melody, and between each group of verses Samson Mugombe (or Cantor Yakobo) read excerpts from various parts of the Old Testament. The melodies were taught by Kakungulu himself. Near the alter stood Samson Mugombe, next to him Zakayo, and the teachers; opposite them were two rows of wide benches. The men sat at the right of the hall and the women at the left. During one of the visits made by Arye Oded to the community in 1965, he was asked if a prayer existed which included all the articles of faith. He indicated the prayer I believe... which includes the thirteen principles of the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimonides) and pointed out that these were usually included in the Jewish prayer books. These principles were translated into Luganda by Isaac Kakungulu, grandson of Semei Kakungulu, and since then were read with the prayers. Samson read each article aloud, and the Congregation repeated it. A prayer and sermon ended the service. In the sermon, Samson Mugombe read verses of topical interest and called on the Congregation to strengthen themselves through belief. Afternoon and evening prayers were recited at home privately.

Hadassah School During the prayers the hands of the people were open, asking the grace from God. This custom was originated by Semei Kakungulu. Although they knew about the religious articles, such as phylacteries and prayer shawls, having seen them in books and pictures, they did not use them as they were unobtainable. At the request of Samson Mugombe, Mr. Oded sent him a prayer shawl, and he alone wrapped himself in it during prayer. Among all the congregants, only Mugombe had a Mezuzah (Hebrew parchment scroll containing Deuteronomy 6:4-9 and 11:13-21 fixed to the doorpost in a wooden or metal case) made of a piece of bamboo fixed to the door of his house. He apparently received it from David Solomon. The rest of Abayudaya did not have them because these too were unobtainable. One of the questions which led to the disagreement between Samson Mugombe and his deputy Zakayo was the direction in which to turn during prayer. Samson instructed his followers to face the West, while Zakayo instructed his to face East, but Mugombe claimed this would be interpreted as praying to the rising sun. During one of the visits made by Oded to the community, he explained that all Jews prayed facing Jerusalem; since then, both Samson and Zakayo agreed to pray in this attitude. The Abayudaya observed all the festivals mentioned in the Bible; they built tabernacles on Succot and slept therein; they did not eat leaven bread during Passover; during Pentecost, the harvest festival, they brought in the first fruits of the earth and then sold them using the money for the needs of the synagogue. The day of atonement was a sacred day, strictly observed as a fast. Samson and Zakayo differed over the dates of festivals, Zakayo claiming the holiday dates fixed by Samson Mugombe were inexact. Samson determined the dates according to an old calender which he possessed, and, on examination, these dates proved to be surprisingly accurate. Arye Oded pointed out this fact to Zakayo, who then agreed to accept Samson's decision on the matter. Even in Kakungulu's time, the Abayudaya knew the Hebrew names of the months of the year, and they used them in their letters. The community observed the practice of ritual slaughter. They did not eat meat from animals slaughtered by strangers or the meat of prescribed animals, nor did they eat blood. Before the ritual slaughter the Shohet (ritual slaughterer) read Leviticus 17:13-16: And whatsoever man there be of the children of Israel, or the strangers that sojourn among you, which huntesth and catcheth any beast or fowl that may be eaten; he shall even pour out the blood there of, and cover it with dust.... Circumcision was the first commandment which Kakungulu accepted at the time of his conversion. Long before he met Joseph male infants were circumcised when they were eight days old. During the ceremony the circumciser read from Genesis 17:10-14: This is my covenant which ye shall keep between me and you and thy seed after thee every man child among you shall be circumcised.... Jonadab Keki acted as a Mohel (a circumciser). Before Joseph's arrival those that wished to accept the Abayudaya religion were baptized in a river. Joseph explained to Kakungulu that there was no need for baptism; the convert needed only to be circumcised and to declare his acceptance of the Commandments. In accordance with those practices, the Abayudaya taught the principles of Judaism to whoever wished to convert. When the teacher was satisfied with the knowledge and convinced of the sincerity of the applicant, texts from Deuteronomy were read to him including 26:16-17: This day the Lord thy God has commanded thee to do these statutes and judgments: you shall therefore keep them with all they heart and with all they soul... The convert was sworn that he accepted Judaism and was given a Biblical name, and if he was not circumcised, this was to be done. The ceremony was concluded with the reading of the entire chapter Isaiah 44: Ye now hear, O Jacob my servant and Israel who I have chosen... Parents were required to ensure their children's education in the Jewish commandments. Instructions were given at the synagogue. The Abayudaya did not know about the laws concerning phylacteries and use them as all Jews do. This desire has not been fulfilled with the reason that they are not obtainable. Marriage was permitted only between Abayudaya. Those who married outside the community and whose spouses did not convert were no longer considered Jews. Joseph taught the Abayudaya about obligatory head covering. On Sabbath and festivals the community wore white robes with full sleeves and colourful sashes, giving their dress a festival appearance. According to Mugombe this was how Joseph dressed for festivals. Kakungulu, influenced by the Malaki usages, refused to take medicines and would not even immunize the animals he owned. His grandson, Isaac Kakungulu related that Semei Kakungulu died of malaria after refusing to take any drugs. Kakungulu based his refusal on Jeremiah 40:11 and on Job 13:4, But ye are forgers of lies, ye are all physicians of no value. The Abayudaya now have repealed this prohibition having learned that it was not a part of modern Jewish practice. In the prayer book compiled by Semei Kakungulu in 1922, which included sections from the New Testament and Christian prayers, Jesus Christ was called Mukama (a translation of Jehovah). After meeting Joseph, Kakungulu instructed that the word Mukama should be deleted and the Luganda word Yakuwa be used when God was mentioned. In 1965 a general meeting of the leaders of the Abayudaya was held over the discontent that had arisen from the elimination of the word Mukama. Samson and Zakayo stressed that in many languages the Creator was called by different names, but in order to emphasize the Abayudaya's disbelief in Jesus Christ they were not to use the word Mukama, so as to prevent confusion among the rank and file Abayudaya. Mugombe and Zakayo's view was unanimously accepted. Kakungulu's death in 1928 deprived the community of strong leadership. Some of the Abayudaya returned to the Malaki sect; others converted to Protestantism or Catholicism. The contest for succession had a harmful effect. Zakayo, Samson Mugombe's rival, broke away with several followers and drew nearer to Christianity. This personal rivalry caused disputes over religious issues. The Abayudaya did not have the means to maintain the synagogue school which they had built. Ibulaim Ndaula Kakungulu, son of the founder, born a Jew and circumcised in accordance with the Law, converted to Christianity while he was a pupil at an Anglican Church school, but still felt close to the community and helped it. As most of the Abayudaya were tenants on the land which he had inherited from his father, Ndaula dealt with them fairly, often intervening on their behalf with the authorities. Another grave danger that threatened them was intermarriage. Owing to the small number of young men in the community, the girls married men of other faiths, and thus became lost to the community. The main factor in its disintegration, however, was undoubtedly the Abayudaya's complete isolation and lack of contact with World Jewry. There was no Jewish body to encourage and help the community, which caused much disintegration and dependency in it. In 1961 the number of the Abayudaya fell to about 300. Subsequently some contacts were made with World Jewry, an aim towards which the Abayudaya had been striving for many years. Following these, some strengthening of the community occured. In 1971 the number had risen to 500 lives and was expected to exceed that due to the proposal the Israel Embassy to Uganda had made to build a permanent synagogue for the community. From 1992 to 1996In the fall of 1992, the leaders of the Abayudaya asked to be assisted in achieving four goals:

Bibliography

Source: The Abayudaya Jews of Uganda; Abayudaya Community in Uganda. Photos courtesy of Noam Katz |

|

In the 1880's, Kakungulu adopted protestantism and

soon became one of the most distinguished leaders of that community

in Uganda. Between 1888 and 1889, Arab ivory and slave traders

succeeded in imposing their rule in Uganda. They supported the

Moslems but in the war which broke out between the latter and the

Christian, Kakungulus military capability was decisive in routing the

Moslems in 1891. In the wars between the Protestants and the

Catholics that followed, Kakungulu helped to defeat the Catholics in

January 1892. His increasing importance and proximity to the royal

family of Buganda were indicated first by his marriage to the

daughter of King Mutesa I (whom he divorced in 1905), and secondly by

his marriage to the daughter of King Kalema, son of Mutesa I.

In the 1880's, Kakungulu adopted protestantism and

soon became one of the most distinguished leaders of that community

in Uganda. Between 1888 and 1889, Arab ivory and slave traders

succeeded in imposing their rule in Uganda. They supported the

Moslems but in the war which broke out between the latter and the

Christian, Kakungulus military capability was decisive in routing the

Moslems in 1891. In the wars between the Protestants and the

Catholics that followed, Kakungulu helped to defeat the Catholics in

January 1892. His increasing importance and proximity to the royal

family of Buganda were indicated first by his marriage to the

daughter of King Mutesa I (whom he divorced in 1905), and secondly by

his marriage to the daughter of King Kalema, son of Mutesa I. As Kakungulu did not clearly define the

organizational structure of the community or the division of

authority, there was often over-mapping in jurisdiction, and

quarrels. Zakayo attempted to acquire the joint position of secular

and religious leader as Kakungulu had. He claimed to be worthy of

this by virtue of his age and learning on matters of Bible and

religion. Samson Mugombe opposed this and claimed the secular

leadership for himself. As a result of this quarrel the community

split into two. It also brought religious differences to the surface.

Zakayo, embittered and disappointed, considered returning to

Christianity. Samson Mugombe, who was younger and more politically

active, succeeded in isolating Zakayo and winning the loyalty of the

community. This division continued until 1962 when Arye Oded visited

the community.

As Kakungulu did not clearly define the

organizational structure of the community or the division of

authority, there was often over-mapping in jurisdiction, and

quarrels. Zakayo attempted to acquire the joint position of secular

and religious leader as Kakungulu had. He claimed to be worthy of

this by virtue of his age and learning on matters of Bible and

religion. Samson Mugombe opposed this and claimed the secular

leadership for himself. As a result of this quarrel the community

split into two. It also brought religious differences to the surface.

Zakayo, embittered and disappointed, considered returning to

Christianity. Samson Mugombe, who was younger and more politically

active, succeeded in isolating Zakayo and winning the loyalty of the

community. This division continued until 1962 when Arye Oded visited

the community.