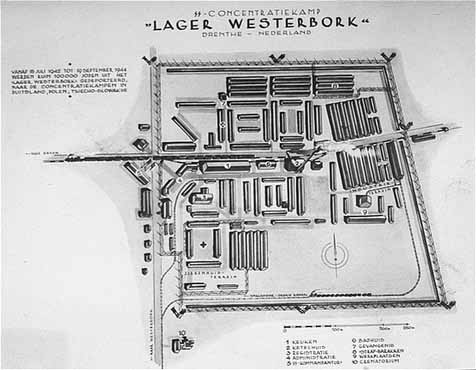

Westerbork Transit Camp: History & Overview

|

The camp of Westerbork was situated about 15 km from the village of Westerbork in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands. This camp was opened by the Dutch authorities during the summer of 1939 to receive the Jewish refugees coming from Germany. The first refugees arrived in Westerbork on October 9, 1939. When the German army invaded Holland, there were 750 refugees in the camp.

On July 1, 1942, the German authorities took control of the camp. Westerbork became officially a transit camp

(Durchgangslager Westerbork). On July 14, 1942, all the Jews were examined by the SS to determine who was able to work or not. The first train arrived on July 15 and left the camp on July 16 with 1,135 Jews. By the end of the month, nearly 6,000 Dutch Jews had reached Auschwitz, where the majority were gassed. Most trains went to Auschwitz, but some transports went to Sobibor, Bergen-Belsen, Theresienstadt, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, and Vittel. Westerbork became known as “the gateway to Hell.”

In the beginning, the transfers were done at the station of Hooghalen. In November 1942, after new rail lines had been constructed, the trains traveled directly to the camp. Nearly every Tuesday for two years, a train with hundreds of Jews left Westerbork.

The camp of Westerbork was a very strange place. There was a school, a hair-dresser, an orchestra (also a complete cabaret group consisting of famous Dutch artists who tried to cheer up the inmates and were required to present all performances in German), and even a restaurant. If a prisoner had enough money, it was possible for him to buy goods that were impossible to find elsewhere in Holland at this time. This comfort

was designed by the SS in order to avoid any problems during the transfers to Auschwitz. Many prisoners thought that conditions would be the same in the camps of Poland. They would sometimes receive letters from Auschwitz or other camps from people who said they were doing well. The Nazis wanted to mislead their victims to believe there was hope for survival.

Members of the Jewish Police, direct arriving Jews |

The most tragic part of the story of this camp is that the SS had very little to do with the transfers: the selections were made by a Jewish organization set up when Westerbork was a refugee camp. The Nazi commandant gave the orders; the Jewish governing

body only carried them out in fear of themselves being deported. Consequently, these Jews were hated.

Also despised was the Jewish Ordedienst (OD), which was founded to maintain security in the camp, and referred to as the Jewish SS.

They informed on inmates to the camp leadership and helped prevent escapes. Only about 300 succeeded in escaping and any family left behind would be deported as punishment.

From Berlin, Adolf Eichmann determined how many Jews should be deported. They were loaded onto train cars carrying their belongings. Once the doors shut, the OD would write in chalk the number of passengers

so the Germans could be sure that everyone arrived at their destination.

The transfers were often done under the control of Dutch policemen. There was a transport to the extermination camps every Tuesday. Before Tuesday, the camp was in panic. Every prisoner feared selection for the next transport. On Tuesday evenings, those who were not selected had just one more week of rest before the next selection.

The SS was responsible for outdoor surveillance until early 1943. The OD and the Dutch military police were in charge inside the camp and were later assigned to outside security as well. In the summer of 1944, they were replaced by a company of the Police Batallion Amsterdam.

From October 1942 SS-Obersturmführer Albert Konrad Gemmeker was in charge of ensuring the efficient deportation of Jews.

Starting on March 5, 1944, camp prisoner Rudolf Breslauer began filming life in Westerbork. The footage showed incoming and outgoing transports, a cabaret performance, workers in a toy factory and the greenhouse in the camp commander’s garden, and morning gymnastics. After Breslauer was deported in September 1944, Wim Loeb finished the film. He made two versions, one for Gemmeker and another that was smuggled out of the camp. The Westerborkfilm was used as evidence during the war crimes trials.

The last transport, carrying 279 people, including 77 children who had been caught hiding, left for Bergen-Belsen on September 13, 1944. Almost 107,000 Jews were transferred through Westerbork during the war. In addition, 247 Sinti and Roma and a few dozen resistance fighters were deported. Only 5,000 people survived.

On April 12, 1945, the Canadian army liberated Westerbork, fewer than 900 prisoners remained in the camp. The day before, the camp was abandoned by Gemmeker, his staff, and the guards. The survivors were not immediately allowed to leave the camp because there were still areas in the Netherlands where fighting continued. The Canadian and Dutch authorities were also suspicious of those who had not been deported and wanted to determine if any had collaborated with the Nazis. Most were kept in Westerbork until July 1945.

Between April and December 1948, the camp served as an internment camp for the SS and other perpetrators, as well as suspected collaborators. It closed on December 1, 1948, and most of the internees were allowed to go home.

In 1949, the Ministry of War took over the camp and used it as a training camp for soldiers who were being sent to fight in the Dutch East Indies. This camp closed in September of that year.

Starting in July 1950, Indo-Dutch people fleeing fighting in Indonesia, or having been released from Japanese internment camps there, traveled to the Netherlands. Westerbork housed some of these refugees and became De Schattenberg. In March 1951, the inhabitants were sent to guest houses and hotels.

In 1951, the camp became a residential settlement for a couple of thousand Moluccans. They had fought for the Royal Netherlands-Indies Army and were loyal to the colonial power and the queen. Many had to leave in 1958 after a fire destroyed three barracks. By 1965, all the Moluccans had been forced out, and the Dutch government dismantled most of Westerbork.

In 1967, the government built the first of 14 radio telescopes on the site. In 1971, the final barracks were demolished or sold to farmers. The only original building remaining on the grounds today is the former camp commander’s house preserved in a glass enclosure. A barrack was constructed with authentic parts to give a sense of life at Westerbork. In 1979, it was decided to build Remembrance Centre Camp Westerbork; it opened in 1983. On De Rampe de Boulevard des Misères, where trains left for the East, two original freight cars have been preserved.

About two miles away, a museum tells the story of the camp. In December 2017, the museum introduced a virtual reality simulation to help visitors envision what took place at Westerbork.

There is a very poignant monument and a very interesting and well-documented memorial center at the site. The monument consists of a piece of railroad track, which at its end is twisted and points into the sky.

Sources: The Forgotten Camps.

Kamp Westerbork.

Matt Lebovic, “At Westerbork, virtual reality simulations ‘recreate’ the Nazi transit camp,” Times of Israel, (January 15, 2018).