Jewish Settlements in the Jordan Valley

By Mitchell Bard (September 2019)

What is the Jordan Valley?

What is the History of Jewish Settlement in the Jordan Valley?

What is the Political Status of the Jordan Valley?

Does the Jordan Valley Hold a Strategic Importance for Israel?

Are Any Plans Being Considered Over the Future of the Jordan Valley?

Annexing the Valley Would Preclude a Peace Agreement

What is the Jordan Valley?

The Jordan Valley (also referred to as the Jordan River Valley) is a segment of the larger Jordan Rift Valley which runs along the entirety of Israel’s eastern border. The Jordan Rift Valley is part of the Great Rift Valley (Syrian-Africa Rift) which runs from Syria to the Zambezi River in Mozambique. The Jordan River flows south from the Sea of Galilee through the Valley for about 185 miles and feeds into the Dead Sea. It separates Jordan, to the east, from Israel and the West Bank.

What is the History of Jewish Settlement in the Jordan Valley?

Following Israel’s War of Independence in 1948, the Jordan Valley was controlled by Jordan and Jews were forbidden to live in the region. The Valley came under Israeli control following the Six-Day War in 1967.

David Newman noted that the geography and climate have discouraged settlement of the Valley. One problem is its distance from Israel’s major population and employment centers. Another is that the “climatic conditions are amongst the harshest in Israel, which explains why for centuries hardly any settlement has ever taken place in this region with the exception of the oasis around Jericho.”

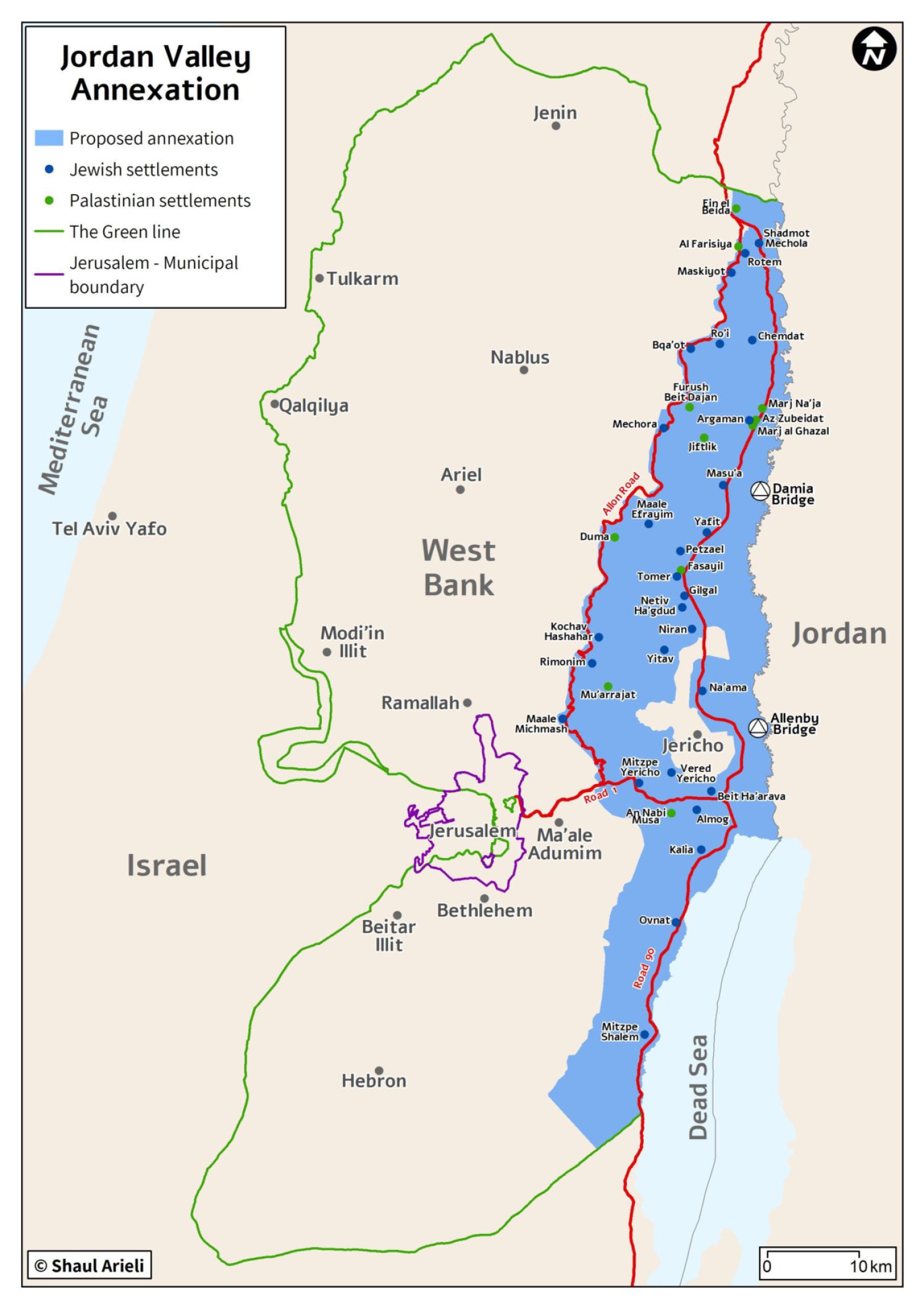

Jewish settlement in the Jordan Valley followed three stages: from 1967 to 1970, six villages were established along the main highway; from 1971 to 1974, five were built along the Valley’s western border; and, from 1975 to 1990, 17 more were spread across the region. Since 1990, development slowed due to political concerns, though the population has continued to grow. Today, the 27 Jewish settlements in the “Jordan Valley bloc” have more than 9,000 residents. Palestinians live in 10 cities and villages, including Jericho, which have a population of approximately 65,000. Most of the area is undeveloped and sparsely populated.

What is the Political Status of the Jordan Valley?

The 1995 Oslo II Accords divided the West Bank into areas A, B and C. Roughly 90% of the Jordan Valley, constituting approximately 30% of the West Bank, is in Area C and under Israel’s control. The city of Jericho and its surrounding villages are part of Area A, which is controlled by the Palestinian Authority; Israeli citizens are not allowed to enter or build in this area.

Does the Jordan Valley Hold a Strategic Importance for Israel?

|

Jordan River water resources and development of the Valley were a concern to Israel and the United States going back to 1953 when President Eisenhower announced the appointment of Eric Johnston to undertake discussions with Israel and the Arab States on a comprehensive plan for the development of the Jordan Valley.

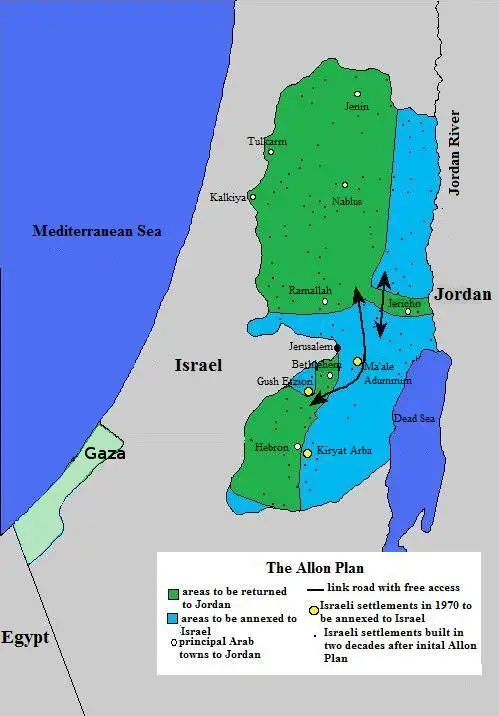

Shortly after the Six-Day War, Israeli Labor Minister Yigal Allon drafted a proposal – the Allon Plan – which envisioned annexing the Jordan Valley. He believed the area was vital to Israel’s security because it provided a buffer zone between Israel and its enemies to the east. The plan stated: “The eastern border of the state of Israel must be the Jordan River and a line that crosses the Dead Sea in the middle…. We must add to the country—as an inseparable part of its sovereignty—a strip approximately 10-15 kilometers wide, along the Jordan Valley.” The Allon Road was subsequently paved and the first Jewish communities were built along Road 90 and the Allon Road.

Yitzhak Rabin, a former chief of staff, shared Allon’s perspective. In his last speech before being assassinated, Yitzhak Rabin flatly stated his opposition to the creation of a Palestinian state and said that as part of a permanent solution to the conflict with the Palestinians, “The security border, for the defense of the State of Israel, will be in the Jordan Valley – broadly defined.”

This remains the consensus view in Israel but there are doubters such as former Mossad Chief Meir Dagan who has said “the Jordan Valley is not vital to Israel’s security.”

Are Any Plans Being Considered Over the Future of the Jordan Valley?

The future of the Jordan Valley remains a contentious issue between Israel and the Palestinians. A variety of compromises have been proposed, but none have been accepted by both sides.

One option raised in past talks involved replacing the Israeli military presence in the Valley with the deployment of international peacekeeping forces. This idea was rejected by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in June 2013 when he said that “Israel cannot depend on international forces for its security … they cannot be the basic foundation of Israel’s security.”

Netanyahu considered various compromises on the status of the Valley. He said, for example, “the Israeli presence in the Jordan Valley could be reassessed over time and could be altered according to Palestinian security performance.” His envoy to peace talks that took place in Jordan in 2012, Isaac Molho, said, Netanyahu spoke of a “military presence along the Jordan River,” but did not demand that Israel maintain sovereignty over the valley. His former Defense Minister, Moshe Ya’alon, said that Netanyahu had agreed to give up control over the Jordan Valley as part of a peace deal during negotiations with the Palestinians in 2014, a claim the Likud Party denied.

In 2013, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry reportedly agreed to allowing an Israeli presence in the Jordan Valley for ten years following the signing of a peace accord during which time PA security forces would be trained to assume control over the region. PA President Mahmoud Abbas rejected the plan.

In December 2013, the Committee for Legislation passed “The Bill to Apply Israeli Law to the Jordan Valley”; however, it was not approved by the Knesset.

In what was widely seen as a play for right-wing votes ahead of the September 17 election, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said on September 10, 2019: “Today I'm announcing my intention, with the establishment of the next government, to apply Israeli sovereignty to the Jordan Valley and the northern Dead Sea. This is our essential safety belt in the east.” Netanyahu’s plan would apply sovereignty to roughly 22% of the West Bank.

Netanyahu’s statement was widely misreported as calling for the annexation of the territory, but he chose his words carefully. He said “applying sovereignty,” which, Erielle Davidson notes, has a different meaning: “A nation cannot annex land over which it already has sovereign claims.”

The government subsequently gave tentative approval for a “new” settlement, Mevo’ot Yericho, which was founded outside Jericho in 1999, but had never been authorized by the government and was therefore considered an illegal outpost. The attorney general said a transitional government could not do this so Netanyahu said it would be formalized by the next government – assuming he won.

|

One explanation for the timing of Netanyahu’s announcement was to attract right-wing voters he needed to be reelected. Another was his apparent belief that President Trump would endorse, or at least not object to the application of Israeli sovereignty to the Jordan Valley given his support for Israel and recognition of Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Immediately after his declaration, the administration officially said only that it had not changed its policy, but, according to one source, the White House does “ not think it precludes the possibility of a political settlement in the future” (Eric Cortellessa, “US says peace deal still possible if Israel annexes settlements, Jordan Valley,” Times of Israel, September 10, 2019).

While the timing, coming just before the election, was controversial, the idea of applying sovereignty to the Jordan Valley was not. Netanyahu’s main opposition, the Blue and White Party, said it was pleased to see he was “adopting Blue and White’s plan for recognizing the Jordan Valley.”

The Israeli public also believes the Jordan Valley is important for security. In one poll, for example, almost 80 percent preferred keeping strategic territory such as the Jordan Valley in any peace agreement. In a more recent poll that asked about annexing all of Area C, not just the Jordan Valley – if the Trump administration supports it – found that 48% of Israeli Jews would support annexation and 28% would not.

Under the Trump peace plan released on January 28, 2020, 30% of the West Bank, including the Jordan Valley, and all Jewish settlements would become part of Israel. After the Palestinians rejected the plan, Israel announcedd plans to act unilaterally and apply sovereignty to some or all the Jewish communities in the West Bank. The Jordan Valley was being considered as one of the first, if not the first, area that would be affected.

Annexing the Valley Would Preclude a Peace Agreement

Eugene Kontorovich, director of the International Law Department at the Kohelet Policy Forum, argued that Netanyahu’s declaration was merely “translating long-standing Israeli consensus into action.”

It also provoked little of the expected uproar in the Arab world. The one exception is Jordan which is understandably more sensitive given that it once occupied the Jordan Valley and has to worry about Palestinian anger given that they make up most of the kingdom’s population. If Netanyahu goes through with his vow, the situation might change, but the immediate reaction suggested the peace treaty with Jordan and Israel’s improving relations with the Gulf States would be unaffected.

Critics of the idea of annexing or applying Israeli sovereignty to the Jordan Valley insist it would kill the peace process and the Palestinians expressed their disapproval. Before the announcement, however, the peace process was moribund. Moreover, the Palestinians have not accepted any offer for independence in all the years Israel has refrained from changing the status of the Jordan Valley.

Applying Israeli sovereignty to the Valley would not preclude negotiations or the possibility of a two-state solution. One reason Israel wishes to control the Valley is to reduce the size of any future Palestinian entity and surround most of its frontier. In addition, an Israeli military presence in the region is meant to enforce the demilitarization of a future Palestinian state by stopping arms smuggling across the Jordan River. It would also provide Israelis with safe and secure access to the Dead Sea, Jordan River and Sea of Galilee.

Any decision regarding the Valley could be reversed or superceded in peace negotiations.

Sources: Herb Keinon, “IDF will remain along Jordan River, PM insists,” Jerusalem Post, March 8, 2011);

“Why Israel Opposes International Forces in the Jordan Valley,” JCPA, (2013);

Barak Ravid, “Netanyahu's Border Proposal: Israel to Annex Settlement Blocs, but Not Jordan Valley,” Haaretz, (February 19, 2012);

Rick Gladstone and Jodi Rudoren, “U.N. Leader Urgently Seeks More Golan Peacekeepers, “New York Times, (June 12, 2013);

Dore Gold, “Why International Peacekeepers Cannot Replace the IDF in the Defense of Israel,” Friends of Israel Initiative, Paper No. 13, (July 25, 2013);

Khaled Abu Tomeh, “Report: Kerry Offers Ten-Year Israeli Presence In Jordan Valley,” Jerusalem Post, (December 10, 2013);

Jonathan Lis, “Ministers Support Bill Annexing Jordan Valley Settlements to Israel,” Haaretz, (December 29, 2013);

“The Jordan Valley’s fate,” Editorial, Jerusalem Post, (December 30, 2013);

Isabel Kershner, “Strategic Corridor in West Bank Remains a Stumbling Block in Mideast Talks,” New York Times, (January 4, 2014);

David Newman, “Borderline Views: The implications of annexing the Jordan Valley,” Jerusalem Post, (January 6, 2014);

Maayana Miskin, “Former Mossad Head: Jordan Valley not Critical,” Arutz Sheva, (May 1, 2014);

Ilan Ben Zion, “Ya’alon: Netanyahu was prepared to cede Jordan Valley,” Times of Israel, (July 27, 2016);

Yaakov Katz, “West Bank Jewish Population Stats,” (Updated to January 1, 2019);

Tamar Hermann and Or Anabi, “Two Weeks to Election Day: IDI Poll Reveals Jewish Israelis are in Favor of a Unity Government,” IDI, (September 3, 2019);

Gil Hoffman, Khaled Abu Toameh and Omri Nahmias, “Netanyahu vows to annex all settlements, starting with Jordan Valley,” Jerusalem Post, (September 11, 2019);

Ben Sales, “Netanyahu’s push to annex the Jordan Valley, explained,” JTA, September 10, 2019);

Ben Hubbard, “Little Outrage in Arab World Over Netanyahu’s Vow to Annex West Bank,” New York Times, (September 10, 2019);

Erielle Davidson, “Israel’s Sovereignty Claims Over The Jordan Valley Are Legitimate,” The Federalist, (September 11, 2019);

Robert Mackey, “Netanyahu Hints Trump Peace Plan Will Allow Israel to Annex Key West Bank Territory,” The Intercept, (September 11 2019);

Jacob Magid, “PM’s Jordan Valley map was error-strewn, but is his vow worth taking seriously?” Times of Israel, (September 12, 2019);

Maj. Gen. (res.) Gershon Hacohen, “The Jordan Valley Is Waiting for Zionist Action,” BESA, (September 16, 2019).